Gotama and Awakening

advertisement

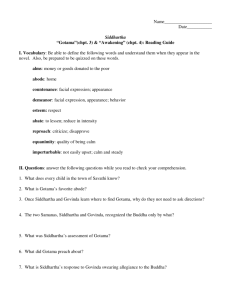

Chapters 3-4: Gotama + Awakening Feraco Search for Human Potential 11 October 2011 Evaluate Your Teachers! What are some qualities of excellent teaching and teachers? Pay attention Make connections Make content interesting Make an effort Now compare teaching with parenting The same qualities – both positive and negative – are present in both Both offer guidance and experience, but neither can offer wisdom That doesn’t make their information irrelevant In fact, their information is necessary in order to place experiences in meaningful contexts The Best of the Best The best teachers in Siddhartha aren’t the ones who try to force others to change or follow They’re the ones who provide Siddhartha with room to gain experience and learn from it, for better or worse Gotama Vasudeva Kamala Bodhisattva vs. Bodhisattva As we mentioned earlier, Gotama and Vasudeva are bodhisattvas, but the latter has a more profoundly positive impact on Siddhartha’s life Gotama’s natural instinct is to teach, and the people most drawn to him are the ones who crave teachers This craving is something Siddhartha would argue will prevent them from ever achieving their goal One Can Learn Much Vasudeva, whom we meet in “Kamala,” takes on a larger role near the story’s end Yes…it is a very beautiful river. I love it above everything. I have often listened to it, gazed at it, and I have always learned something from it. One can learn much from a river. Rather than try to guide Siddhartha through explicit instructions or commandments, he merely provides Siddhartha with a space to explore and experience life in all its forms The Man by the River As a ferryman, he gets to see people from all walks of life Contrast that with Siddhartha’s views of the world and its people at the beginning of Chapter 2 – scornful, ignorant rejection vs. curiosity During the time that Siddhartha spends living with him, he occasionally offers up some advice, but doesn’t mind that his younger companion won’t follow it He knows Siddhartha will mess up badly, and he’s OK with that for two reasons Flashlights Firstly, experience makes things “realer” – more meaningful to the person Remember the flashlight… Secondly, one has to have a range of experiences – good, bad, and everything in between – in order to truly live At some point, teaching becomes a way of sheltering others – of preventing mistakes that would occur otherwise Sheltering doesn’t work; it only serves to fight against the Universal Truths The Brahmin tried sheltering Siddhartha Govinda does it to himself! Inevitable Epiphany It’s therefore necessary for Siddhartha to strike off on his own The epiphany in “Awakening” is, in one sense, inevitable In “Gotama,” the chapter’s first encounter immediately sets the tone for what follows Govinda wants to hear the woman talk more about Gotama As though he could gain something by listening to someone else talk! Siddhartha just wants to move along The Catalyst Both discover that the path to Gotama is being walked by many others When they reach the spiritual leader, it’s not too surprising that Siddhartha finds a way to resist continuing with him, nor that Govinda proves to be an eager follower After all, Gotama provides both men with the ideal catalyst for further action The nature of his presence requires each man to make a decision that reflects his personality The First Still, Siddhartha is impressed by Gotama After all, it’s the first time he’s met a man who’s achieved what he aims to achieve It’s not that he doesn’t believe in what Gotama says (although he does point out the loophole) – he does, at least to an extent But he protests that Gotama cannot possibly transfer the understanding he reached under the bo tree – the “secret of what the Illustrious One himself experienced – he alone among hundreds of thousands” Insufficiency Siddhartha believes that no doctrine can exceed Gotama’s Since Gotama’s teachings proved insufficient for him, it stands to reason that no teachings will suffice No other teachings will attract me, since this man’s teachings have not done so. Siddhartha and Govinda are two sides of the same coin, but their opposite approaches to life and discovery drive them apart here Renounce Connection When Govinda chooses to follow the Buddha, he renounces human connections This is something Gotama preaches, but something Siddhartha insists at the end of the book is inconsistent with how the Buddha lives his life Notably, he doesn’t realize that he’s doing so, that his decision will cost him his companion But that’s partly a reflection of Govinda’s approach: follow others in search of understanding without bothering to check for understanding first Thirsty for Knowledge In fact, Govinda prefers to follow others until someone/something else convinces him to follow it instead Had he considered his decision more carefully, not only would he have realized the cost of his choice, but he’d have heard Gotama say something significant The teaching which you have heard, however, is not my opinion, and its goal is not to explain the world to those who are thirsty for knowledge. The Point of Portrayal There’s nothing remarkable about Govinda’s approach Indeed, it’s how most people approach their lives – which was the point of his portrayal However, such an approach ultimately won’t work for him, nor does it for Siddhartha Notice that Govinda does make decisions; it’s just that his decisions make him more passive rather than active He is, as Siddhartha describes him, an excellent shadow for greater men Cleverness Cleverness implies intelligence for gain, particularly immediate gain You’re clever when you can trick someone into doing your bidding, for example, or puzzle your way out of a difficult situation Connotatively, wisdom is more placid, peaceful, and unfocused on gain – it’s meant to be shared (if not transferred…if that makes any sense) It requires a wide, long-term, all-encompassing perspective here The Buddha warns Siddhartha to “be on…guard against too much cleverness,” but Siddhartha doesn’t heed his advice His view of the people is the town bears the mark of a man who considers himself cleverer, if not wiser, than all others Thus Siddhartha leaves the grove, ready for his awakening Out of the Grove “Awakening” finds Siddhartha leaving the Jetavana grove (a special sort of mini-forest, a cultivated wilderness) and initially intending to head back to the forest, only to realize midchapter that he cannot go home He is no longer the person he was when he left, and nothing waits for him at the other end of that path Indeed, Siddhartha realizes that “he [is] no longer a youth; he [is] a man. He realize[s] that something ha[s] left him, like the old skin that a snake sheds. Something [is] no longer in him, something that had accompanied him right through his youth and was part of him: this was the desire to have teachers and to listen to their teachings.” Next, he decides, “I am no longer what I was, I am no longer an ascetic, no longer a priest, no longer a Brahmin. What then shall I do at home with my father? Study? Offer sacrifices? Practice meditation? All this is over for me now.” To Study the Self He realizes that his attempts to destroy the Self stemmed from his fear and misunderstanding of it, and that said attempts had left him further from enlightenment rather than closer He decides that he is separate and different from everyone else, and that he must no longer try to escape from himself Intending to learn how to understand himself better, he decides to leave the natural/semi-cultivated world behind in favor of something new – which, as it so happens, is the town across the river… a a The first forty years of life give us the text; the last thirty supply the commentary. – Arthur Schopenhauer My mother said to me, “If you are a soldier, you will become a general. If you are a monk, you will become Pope.” Instead I became a painter, and became Picasso. – Pablo Picasso Until I saw Chardin’s painting, I never realized how much beauty lay around me in my parents’ house, in the halfcleared table, in the corner of a tablecloth left awry, in the knife beside the empty oyster shell. – Marcel Proust a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a a