The Boundaries of Free Expression

advertisement

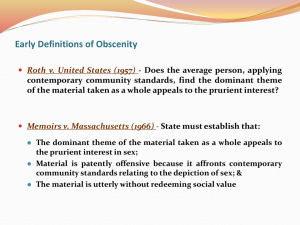

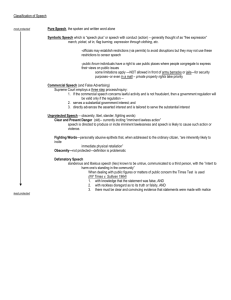

The Boundaries of Free Expression: Obscenity The Bill of Rights Institute Tribune Tower Chicago, IL, November 7, 2005 Artemus Ward Department of Political Science Northern Illinois University Regina v. Hicklin (1868) In this British case, the Court asked, “whether the tendency of the matter charged as obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of this sort might fall.” There were three important parts to the Hicklin case: 1. required the material to meet a stringent level of acceptability—whether the material could be seen by a child; 2. it did not require that the publication be considered as a whole, instead an entire work could be declared obscene based on one of its parts; 3. courts did not have to consider the social value of the works in question. As a result, the Hicklin standard left a wide range of expression unprotected. Applying Hicklin The U.S. Supreme Court not only adopted the Hicklin standard but strengthened it. In Ex parte Jackson (1878) the Court upheld the Comstock Act, which made it a crime to send obscene materials, including information on abortion and birth control, through the U.S. mail. But by the 1930s and 1940s lower courts were handing down conflicting rulings and by the 1950s the pornography industry was flourishing. Finally, the Court spoke in Butler v. Michigan (1957) by striking down a state law that made it a crime to distribute material “found to have a potentially deleterious influence on youth.” But if Hicklin’s child standard was no longer valid, what was the standard for judging obscenity? Roth v. United States (1957) The U.S. indicted Samuel Roth for violating federal obscenity law, specifically for sending “obscene, indecent, and filthy matter” through the mail. Among those materials was an advertisement for Photo and Body, Good Times, and American Aphrodite Number Thirteen. At Roth’s trial, the judge instructed the jury with this definition of obscenity: the material “must be calculated to debauch the minds and morals of those into whose hands it may fall and that the test in each case is the effect of the book, picture or publication considered as a whole, not upon any particular class, but upon all those whom it is likely to reach. In other words, you determine its impact upon the average person in the community.” The jury found Roth guilty and the judge sentenced him to the maximum punishment of five years in prison and a $5,000 fine. Roth v. United States (1957) Justice Brennan wrote for a 6-3 majority: 13 of the 14 original states provided for the prosecution of libel, and all of those states made either blasphemy or profanity, or both, statutory crimes. This makes it clear that the First Amendment did not protect every utterance. “Implicit in the history of the First Amendment is the rejection of obscenity as utterly without redeeming social importance.” The 1st Amendment was designed to protect the unfettered interchange of ideas for the bringing about of political and social changes desired by the people. There are now obscenity laws in all states, Congress has passed numerous obscenity laws, and over 50 nations have agreed. Roth v. United States (1957) “Sex and obscenity are not synonymous. Obscene material is material which deals with sex in a manner appealing to prurient interest. The portrayal of sex, e.g. in art, literature and scientific works, is not itself sufficient reason to deny material the constitutional protection of freedom of speech and press. Sex, a great and mysterious motive force in human life, has indisputably been a subject of absorbing interest to mankind through the ages; it is one of the vital problems of human interest and public concern. . .” The constitutional test is “whether the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole appeals to prurient interest.” pru·ri·ent (adj.) Inordinately interested in matters of sex; lascivious. --American Heritage Dictionary Roth v. United States (1957) Justice John Marshall Harlan II concurring and dissenting in part: “[This problem] cannot be solved in a generalized fashion. Every communication has an individuality and ‘value’ of its own. The suppression of a particular writing or other tangible form of expression is, therefore, an individual matter, and in the nature of things every such suppression raises an individual constitutional problem, in which a reviewing court must determine for itself whether the attacked expression is suppressible within constitutional standards. Since those standards do not readily lend themselves to generalized definitions, the constitutional problem in the last analysis becomes one of particularized judgments which appellate courts must make for themselves.” Roth v. United States (1957) Justices Douglas & Black dissenting: “When we sustain these convictions, we make the legality of a publication turn on the purity of thought which a book or tract instills in the mind of the reader. I do not think we can approve that standard and be faithful to the command of the First Amendment. . .” “I reject the implication that problems of freedom of speech and of the press are to be resolved by weighing against the values of free expression, the judgment of the Court that a particular form of that expression has ‘no redeeming social importance.’ The First Amendment, its prohibition in terms absolute, was designed to preclude courts as well as legislatures from weighing the values of speech against silence. The First Amendment puts free speech in the preferred position. . .” “I would give the broad sweep of the First Amendment full support. I have the same confidence in the ability of our people to reject noxious literature as I have in their capacity to sort out the true from the false in theology, economics, politics, or any other field.” Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964) The Court viewed the film Les Amants “The Lovers” and said the contemporary standards mentioned in Roth were national standards. In dissent, Chief Justice Earl Warren said it should be local community standards. Justice Potter Stewart was so disgruntled with this area of the law that he said “I shall not today attempt to further define hard-core pornography . . . But I know it when I see it.” The justices regularly had movie days where they decided whether certain films were obscene. Memoirs v. Massachusetts (1966), The Fanny Hill case The Court ruled on whether John Cleland’s 1749 erotic novel that traces the escapades of a London prostitute was obscene. Justice Brennan said that as long as a work had “a modicum of social value” it could not be judged obscene. The work had to be “utterly without redeeming social value” for it to be judged obscene. But only two other justices joined Brennan’s opinion. It was unclear whether hard-core pornography (that had some artistic or social merit) could be banned. By the end of the 1960s, the Court could not agree on a standard of review, but they did agree on speech protectiveness in this area so that virtually every obscenity conviction that came before them was summarily overturned. The country was approaching the “end of obscenity.” Richard Nixon was elected in 1968. He criticized the liberal Warren Court and remade the bench with four appointments. Miller v. California (1973) Marvin Miller, a vendor of so-called adult material, conducted a mass-mail campaign to drum up sales for his books. The pamphlets were fairly explicit, containing pictures of men and women engaging in various sexual activities, often with their genitals prominently displayed. Had Miller sent the brochures to interested individuals only, he might not have been caught. But because he did a mass mailing, some pamphlets ended up in the hands of people who did not want them. Miller was arrested when the manager of a restaurant and his mother opened of the envelopes and complained to the police. Miller v. California (1973) “The basic guidelines for a trier of fact must be (a) whether “the average person, applying contemporary community standards” would find that the work, taken as whole, appeals to the prurient interest; (b) whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and (c) whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. We do not adopt the “utterly without redeeming social value” test of the Fanny Hill case. Miller v. California (1973) The state can regulate: “(a) patently offensive representations or descriptions of ultimate sexual acts, normal or perverted, actual or simulated; (b) patently offensive representation or descriptions of masturbation, excretory functions, and lewd exhibition of the genitals. Sex and nudity may not be exploited without limit by films or pictures exhibited or sold in places of public accommodation any more than live sex and nudity can be exhibited or sold without limit in such public places.” Miller v. California (1973) “Under a National Constitution, fundamental First Amendment limitations on the powers of the States do not vary from community to community, but this does not mean that there are, or should or can be, fixed, uniform national standards of precisely what appeals to the ‘prurient interest’ or is ‘patently offensive.’ These are essentially questions of fact, and our Nation is simply too big and too diverse for this Court to reasonably expect that such standards could be articulated for all 50 States in a single formulation, even assuming the prerequisite consensus exists.” One can’t expect jurors, drawn from local communities to divine some kind of national standard. States can’t try to structure their laws around national standards. “It would be an exercise in futility.” “It is neither realistic or constitutionally sound to read the First Amendment as requiring that the people of Maine or Mississippi accept public depiction of conduct found tolerable in Las Vegas or New York City. People in different States vary in their tastes and attitudes.” Obscenity under the Miller test Miller marked an important change in obscenity jurisprudence. Between 1957 and 1969—the heyday of the Roth test—the justices supported First Amendment claims in 88% of their obscenity decisions; that number dropped to 32% after Miller (19701988).