Only following orders

advertisement

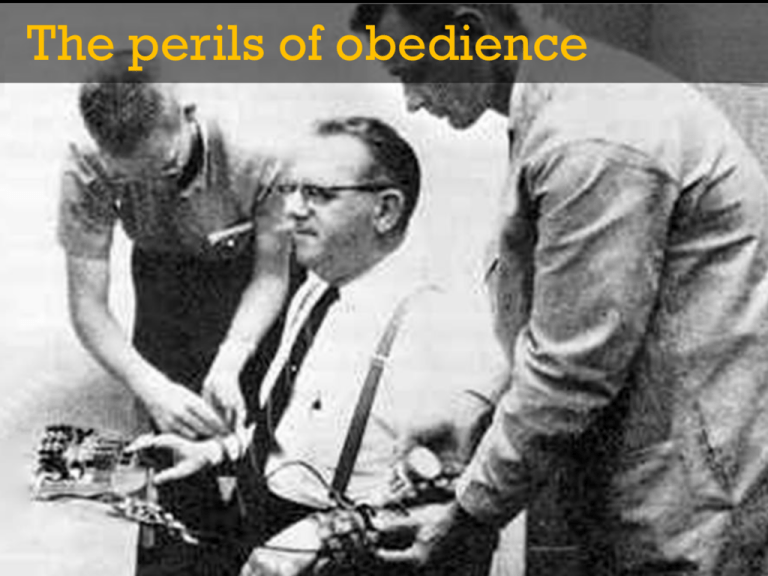

The perils of obedience The Milgram Shock Experiment (1961) The results What percentage of “teachers” do you think continued to the maximum voltage of 450 volts? Before the experiment, Milgram asked his colleagues in the psychology department how many subjects they thought would go all the way to 450 volts. They all assumed that it would be 0-3 out of 100 subjects who would go all the way, and that these would clearly be psychopaths. The results What were the actual results? 65% of participants – basically 2 out of 3 – took it all the way to 450 volts. The Milgram Experiment Are people basically aggressive and ready to inflict pain as soon as they are given an excuse? Did these participants come from a sadistic fringe of society for some reason? “The Banality of Evil” “The Banality of Evil” Variations on the experiment Milgram performed this experiment many times, varying the “set-up” slightly in each new version. The alternate versions demonstrate that three things can strongly influence the subject’s “compliance” with the experimenter’s instructions: Responsibility: in some versions, the subject is allowed to decide when to go on or to stop Proximity: in some versions, the subject of the experiment is brought closer to the “learner”; in others, to the experimenter. Conformity: when other actors are introduced as fellow “teachers,” they will either protest and leave, or comply with the experimenter. Subjects often follow the lead of the actors. Responsibility When the subject can choose the voltage, the average maximum level of shock chosen is 60 volts. There were 40 subjects. 3 never went beyond the lowest possible shock (15 volts). 28 went no higher than 75 volts. 95% of subjects never went beyond the first loud protest made at 150 volts (most of them not having gone beyond 75). Two subjects (5%) did go into the sadistic range. One subject went to 325 volts and one subject (evidently the “psychopath”) did go all the way to 450 volts. Proximity When the “experimenter” is not present in the room with the subject, compliance drops to 33% When the “learner” is across the table from the “learner,” compliance drops to 9% When the subject must physically interact with the “learner” ( holding the “learner’s” hand on what you believe to be an electrical plate) compliance drops to its lowest point. On the other hand, when the “learner” is never seen at all by the subject, compliance goes up to 90% … ! Conformity In some versions of the experiment, Milgram placed actors alongside the real subject of the experiment. They would pretend to have been assigned the “teacher” role as well. Sometimes, Milgram would have arranged for these actors to comply with the experiment; other times, they would refuse to continue. Conformity Compliance rises slightly if the other teachers appear willing to continue. But, when even one of the fellow “teachers” refuses to continue, 80% of subjects will also refuse. When all of the “fellow teachers” refuse to continue, over 90% of subjects will also refuse to continue. Milgram’s conclusions “Only following orders” “Not my brother’s keeper” Alienation and the Division of Labour “Only following orders” Most people find they do not have the power to resist even the least threatening forms of authority. p. 208 “Not my brother’s keeper” Most people do not consider themselves responsible for evil that other people do in their presence. p. 211 The division of labour At the end of the article, Milgram suggests that the society in which we live encourages in many ways our failure to feel personal moral responsibility. Government bureaucracy and capitalist division of labour alienate us from the origins and consequences of our actions, leading us to feel that we are a small and insignificant part of a larger picture we can’t see and over which we have no control. Organized evil in society pp. 211-212 Resistance There is one glimmer of hope in the variations on the experiment that Milgram tried. Even one person standing up and refusing to continue doubled the number of other participants who refused to go on. Rebels show us that there is an alternative to a system we assume we can’t change. The first person with the strength to say no gives strength to many more people who have been going along on auto-pilot, doing evil. Waking up It isn’t necessarily will power or even courage that people need to stop participating in evil. Sometimes, they just need to think about what they are doing. One person saying no, and opting out of the evil can be enough to “wake up” many others to the reality of the evil to which they are contributing. The actor who refused to continue in some variants of the Milgram experiment didn’t give the other participants more courage or will power. Instead, he “raised their consciousness,” making them aware that what they were doing was wrong, and that resistance was both possible and in this case even easy. The value of the rebel One person staying clear-headed and lucid among the herd, and prepared to speak up and bear witness to what is really going on, even in the face of authority and peer pressure is sometimes all it takes to put an end to organized evil. But that is what it takes. Quiz (2 marks) 1. Explain the difference between formal and substantive equality; give an example. 2. Define and explain the Original Position and The Veil of Ignorance; give an example of a situation where one might try to use them. 3. What is the idea of The Banality of Evil, as used by Hannah Arendt and Stanley Milgram? 4. According to Stanley Milgram, how does Karl Marx’s concept of the Division of Labour relate to the findings in his shock experiment?

![milgram[1].](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005452941_1-ff2d7fd220b66c9ac44050e2aa493bc7-300x300.png)