Christine Schulze

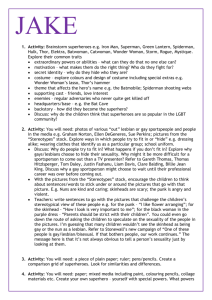

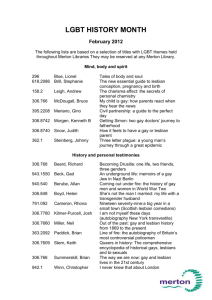

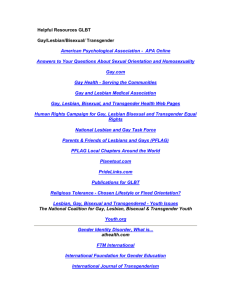

advertisement