216F07L8

advertisement

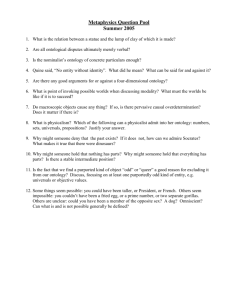

Critical Theory and Technology “As a historical project, technicity has an internal sense of its own: … instrumentality as a way to release man from labour and anxiety, as a way to pacify the struggle for existence. … [But] insofar as society has made an abstraction of technology’s ultimate purpose, technology itself perpetuates misery, violence and destruction” Marcuse (From Ontology to Technology, 124) Preamble Marcuse’s warning: In both capitalist and socialist societies, “an entire dimension of human reality” has been suppressed (119). We can’t look at individual ideological forms alone to diagnose the problem; rather, we need to consider the assumptions underpinning all ideological forms. For Marcuse, this requires us to consider what made possible “both the technological domination of the world and the universal administration of society” (119-120). 2 From Ontology to Technology What does ‘ontology’ mean? A sub-field of metaphysics. It examines the idea of ‘what there is’—the kinds of objects and their nature in the universe. For example, what kind of being is man? Heidegger: we are the being for whom the question of being matters. 3 From Ontology to Technology In a science-dominated worldview, there is no room for these sorts of questions. For Popper, a hypothesis is ‘scientific’ if it is potentially falsifiable. Are metaphysical claims scientific, i.e. falsifiable? How do we falsify claims? Empirically, but can metaphysical claims be decided empirically? No. They are conceptual issues. So, according to Popper, metaphysics is not science. 4 From Ontology to Technology Marcuse: under science, “an entire dimension of human reality is … suppressed” (119). How did the metaphysical questions fall by the wayside? Scientific reasoning focuses on explanations based on efficient causes. It abandoned the Aristotelian four-fold notion of ‘cause’: formal, material, efficient and final. 5 From Ontology to Technology The table is made of wood (material cause) Having four legs and a flat top makes this artefact a table (formal cause) The carpenter made the table (efficient cause) Providing a surface to work is what a table is for (final cause) Final causes—reasons for why certain things are the way they are. 6 From Ontology to Technology In science, explanation in terms of final causes have been abandoned. We no longer ask: why does the heart beat? For Marcuse, this is fundamental for it means we no longer ask questions like, does what is life for? Does life have meaning? This is not a scientific question, but that doesn’t mean we can’t ask it. He is, of course, unfair here for those sorts of questions are being asked. Or is he being unfair? 7 From Ontology to Technology One consequence of the emergence of the ‘new science’: “In its effort to establish the physical mathematical structure of the universe, [science] also abstracted itself from the concrete individual and its ‘sensuous body’. … [Science has become] a logical system of propositions which guide the use and the methodological transformation of nature and which tended to produce a universe controlled by the power of man” (120) 8 From Ontology to Technology For Marcuse, ‘technology’ concerns what we can do with things. Things—mere objects—are instruments for our projects. The world in which science/technology operates consists just of ‘matter’. Why are values excluded? Science seeks only quantifiable results. The kind of reasoning that matters most here is instrumental, means-end. It has a hypothetical form: If … then … 9 From Ontology to Technology “The universe of discourse [is filtered] for the use of … specialists and experts who calculate, adjust … without ever asking for whom and for what. The occupation of the specialists is to make things work, but not to give an end [i.e. a telos] to the process. … Being assumes the ontological characteristic of instrumentality, by its very structure this rationality is susceptible to any use and to any modification” (122). 10 One-Dimensionality Man and Nature have become one-dimensional. What does one-dimensional mean? The context of “efficient, theoretical and practical operations” (122). Efficiency is the new mantra. Whereas in “pre-technological” times, man existed in two dimensions: “The capacity to envisage another mode of human existence within reality, and the ability to transcend facticity [i.e. what the situation is now] towards its real possibilities” (121). 11 Scientific ‘neutrality’ For Marcuse, the present course of science lies with its self-understanding: as a ‘neutral’, or ‘objective’, engagement with ‘nature’. Such understanding leads to further domination of man and of nature, where “life itself has become merely a means of living” (125). Marcuse rejects that science/technology is ‘neutral’: Science is not an abstract enterprise—it reflects “a way of existing between man and nature” (123). Science has a ‘trajectory’. 12 What price neutrality? The question that Marcuse poses is: what price did we pay when science is understood as a “logical system of propositions”? Traditionally, technology had an end, a telos: to satisfy man’s basic needs, to “release man from labour and anxiety, as a way to pacify the struggle for existence” (124). But now ‘man’ appears as a variable in an equation governed by efficiency. 13 What price neutrality? What remains in this view of science/technology is a double domination: the technological domination or control of nature, and the domination or control of man insofar as man is part of nature. How is man dominated by science/technology? “Universal administration of society” (120). 14 Technology and subjugation Marcuse: “all progress … is accompanied by a progressive repression and a productive destruction” (125). This path is driven by a particular understanding of science/technology: “pure instrumentality deprived of its ultimate purpose has become a universal means of domination. … Technology itself perpetuates misery, violence and destruction” (124). 15 Technology and subjugation So called progress brings about even further subjugation. Individuals in contemporary industrial societies are required to turn away from “satisfaction and rest” (125) as their instincts tell them: “The human organism ceases to exist as an instrument of satisfaction … instead it has become an instrument of work and renunciation” (ibid). Civilization becomes just “man’s subjugation to work” (ibid.). 16 Marcuse: “a new reality principle” Yet, “there is a control over man [and nature] which is repressive, and there is a control over man [and nature] that is liberating” (127). How so? Marcuse hints at a “new reality principle” (126). He acknowledges that all societal forms require individual to labour and some form of ‘repression’ on those individuals (ibid.)—imagine a society in which every individual is free express his/her desires and passions. 17 Marcuse: “a new reality principle” But once we recognize the end of technology, then the need to labour can be eased, if not abolished. Life is not “merely a means for living” (125). What does that mean? Instead of struggling for existence, existence can be enjoyed (126). This makes possible “an upheaval in the order of instincts and needs (ibid.), which will have consequences for the need to treat it merely as an instrument for production. 18