Chandler, David G. The Campaigns of - SAMS Comp Prep 13-01

advertisement

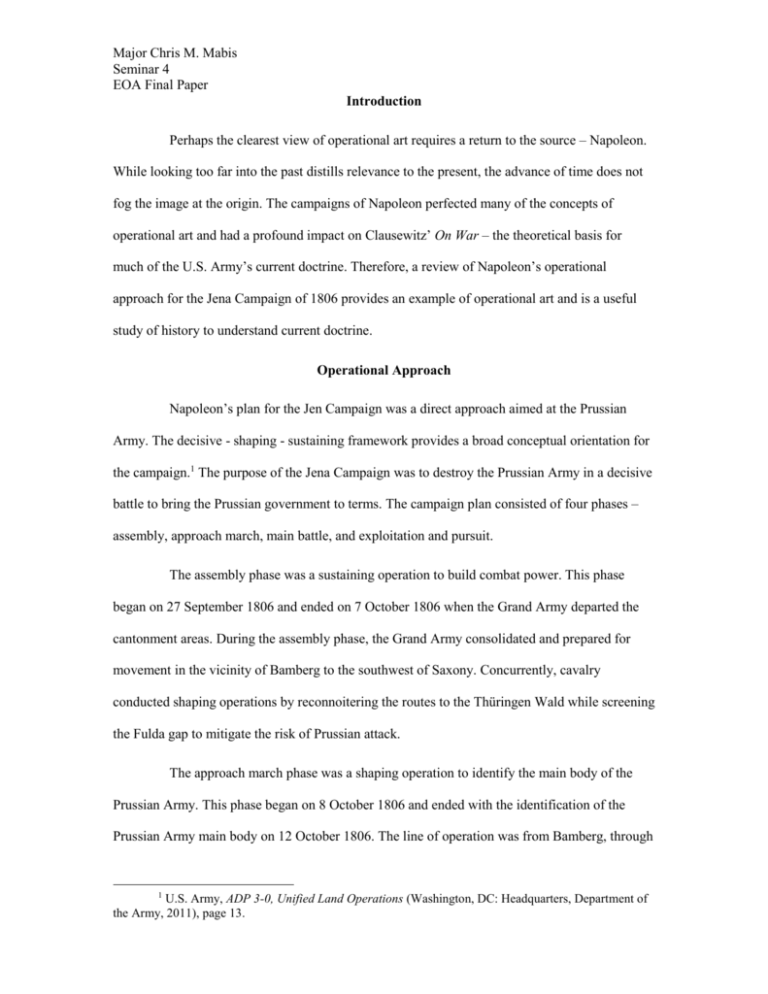

Major Chris M. Mabis Seminar 4 EOA Final Paper Introduction Perhaps the clearest view of operational art requires a return to the source – Napoleon. While looking too far into the past distills relevance to the present, the advance of time does not fog the image at the origin. The campaigns of Napoleon perfected many of the concepts of operational art and had a profound impact on Clausewitz’ On War – the theoretical basis for much of the U.S. Army’s current doctrine. Therefore, a review of Napoleon’s operational approach for the Jena Campaign of 1806 provides an example of operational art and is a useful study of history to understand current doctrine. Operational Approach Napoleon’s plan for the Jen Campaign was a direct approach aimed at the Prussian Army. The decisive - shaping - sustaining framework provides a broad conceptual orientation for the campaign.1 The purpose of the Jena Campaign was to destroy the Prussian Army in a decisive battle to bring the Prussian government to terms. The campaign plan consisted of four phases – assembly, approach march, main battle, and exploitation and pursuit. The assembly phase was a sustaining operation to build combat power. This phase began on 27 September 1806 and ended on 7 October 1806 when the Grand Army departed the cantonment areas. During the assembly phase, the Grand Army consolidated and prepared for movement in the vicinity of Bamberg to the southwest of Saxony. Concurrently, cavalry conducted shaping operations by reconnoitering the routes to the Thüringen Wald while screening the Fulda gap to mitigate the risk of Prussian attack. The approach march phase was a shaping operation to identify the main body of the Prussian Army. This phase began on 8 October 1806 and ended with the identification of the Prussian Army main body on 12 October 1806. The line of operation was from Bamberg, through 1 U.S. Army, ADP 3-0, Unified Land Operations (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2011), page 13. the Thüringen Wald, to Berlin. The Grand Army, organized in a mutually supporting square battalion formation, maneuvered on three mutually supporting roads. Decisive points based on key terrain were initially a line on the Saale River between Hof and Saalfield, then the line between Leipzig and Dresden approaching the Elbe River. The main battle phase was the decisive operation to destroy the Prussian Army. This phase began on 13 October 1806 and ended with the destruction and withdrawal of what Napoleon believed to be the Prussian Army main body on 14 October 1806. Upon identification of the main body of the Prussian Army, the Grand Army converged on a single point to mass overwhelming combat power against the Prussian Army. The Corps in contact fixed the enemy, while adjacent corps moved to the left or right flanks to provide additional combat power. Corps out of contact maneuvered to the flank of the enemy to isolate the enemy main body. Additional corps out of contact prepared to follow and assume the fixing force to reinforce success. The exploitation and pursuit phase was a shaping operation to ensure the destruction of the Prussian Army. This phase began on 15 October 1806 and ended on 1 November 1806 with the capture of Berlin and advance to the Oder River. The Grand Army once again transitioned to the square battalion. Based on the withdrawal of the Prussian Army, Napoleon now pursued a line of operations on four main roads between Magdeburg and Wittenberg. This maneuver severed the Prussian Army’s line of communication with Berlin and pushed them into northern Prussia. This led to the capture of two Prussian formations between 28 October and 7 November. While remnants of the Prussian Army continued to fight, the destruction of the Prussian Army and the capture of Berlin caused the Prussian government to seek peace in early 1807. Operational Environment How did Napoleon devise the operational approach to the Jena Campaign? To develop the operational approach, Napoleon considered both the current situation and the desired end state 2 – the operational environment.2 Starting with Napoleon’s objectives and end state, the operational environment takes shape by deductively considering the terrain, threat, and friendly forces. Napoleon’s objectives and end state were clear. Strategically, his objectives were to gain a source of men and money for future campaigns, secure a base of operations east of the Rhine, and control a defensive buffer zone between France and Russia.3 Napoleon saw the Prussian Army as the center of gravity for Prussia. Thus, he pursued an operational objective of driving on Berlin in order to lure the Prussian Army into a decisive battle before Russian aid was available.4 Therefore, Napoleon envisioned his end state as – the Prussian Army defeated in a decisive battle, Prussia incorporated into the French Empire, the combat power of the Grand Army preserved, and the border pushed east through Prussia to the Russian frontier. Terrain begins to define the operational environment. Napoleon sought a decisive battle on the Elbe River approaching Berlin.5 A western approach from Wesel to Berlin was direct and covered the easiest terrain. However, this approach would cause the Grand Army to relocate and the multiple river crossings in northern Prussia were easily defended. A southern approach from either Mainz or Bamberg was advantageous based on the location of the Grand Army. However, Saxony was more rugged. Forested low mountains gave way to hills and rolling plains. Roads were less plentiful, but they were generally mutually supporting and the rivers provided flank protection. Therefore, a southern attack carried more risk based on the terrain while presenting opportunity for quickly gaining the central position between Leipzig and Dresden – key terrain identified by Napoleon.6 2 U.S. Army, ADRP 5-0, The Operations Process (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2012), page 2-6. 3 David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon (New York: Scribner, 1973), page 449. 4 Ibid., page 462. 5 Ibid., page 464. 6 Ibid., page 464. 3 Analysis of the threat through a wide lens, then focusing on Prussia is useful to describe the nature of the forces opposing Napoleon. In 1806, Napoleon faced the fourth coalition of Great Britain, Russia, Prussia, Sweden, and Saxony. Great Britain commanded the seas but posed little threat on the continent. In late 1805, Napoleon decisively beat an Austro-Russian coalition at Austerlitz, neutralizing Austria and causing Russia to withdraw. Until Russia reconstituted their army, Prussia remained the only major land-based power challenging France. Therefore, Napoleon understood that he needed to guard against Great Britain, keep a watchful eye on Austria, and strike quickly before Russia could come to the aid of Prussia. Narrowing the focus on Prussia specifically, Napoleon respected the Prussian Army of Frederick the Great, but held the current Prussian leadership under Frederick William III in contempt.7 The Prussian Army was nearly the size of the Grand Army and was well disciplined. Prussia’s greatest deficiencies were the lack of an organized Prussian staff, inadequate leadership under Frederick William III, and archaic generals clinging to past glory.8 While the Prussians enjoyed an advantage in mobilization time, the Prussian leadership proved indecisive, squandering any advantage the Prussian Army possessed. Regardless, Napoleon believed that the Prussian Army would defend south of Berlin, using terrain to trade space for time until the Russians could join the battle. Therefore, it was essential for the Grand Army to strike quickly and gain control of terrain that denied Prussia assistance from Russia. The same method of analysis describes the disposition of friendly forces. The wide view shows how Napoleon arranged forces across the continent to protect the Grand Army and allow freedom of maneuver. In the north, the Dutch Army secured the northern flank around Wesel and provided a hedge against British incursions on the continent while in the south, the 7 David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon (New York: Scribner, 1973), page 444. David G. Chandler Ph.D., “Napoleon, Operational Art, and the Jena Campaign,” in Historical Perspectives of the Operational Art, ed. Michael D. Krause and R. Cody Phillips (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 2007), page 37. 8 4 Army of Italy provided a hedge against Austria.9 Along the Rhine River, a corps of the Grand Army blocked any Prussian thrust into France.10 The Grand Army occupied a relatively safe base centered on Bamberg behind the Thüringen Wald. Narrowing the scope, the Grand Army of 1806 was the most integrated and best-trained force that Napoleon ever commanded.11 The six corps making up the Grand Army were seasoned veterans of recent campaigns at Ulm and Austerlitz.12 Each corps was an integrated team of infantry, cavalry, artillery, that operated independently, but could mass on a central point for the decisive battle. Napoleon’s corps commanders were young and each corps possessed a staff capable of processing information quickly.13 Based on these advantages, Napoleon pursued the square battalion formation for the Jena Campaign. The square battalion allowed rapid maneuver that offered mutual protection and could meet an enemy attack from any direction.14 The Problem Statement The operational environment aided Napoleon in formulating the problem statement. How does the Grand Army destroy the Prussian Army in a decisive battle to force the Prussian government to terms? Speed prevents aid from reconstituted Russian forces. Therefore, the quickest way to entice the Prussian Army to battle is to threaten Berlin by seizing the central position between Leipzig and Dresden. The Grand Army, centered on a base of operations in Bamberg, faces the Prussian Army, mobilizing south of Berlin, of nearly equal size. Maneuver to the north, attacking through Wesel or Fulda incurs risk for time and requires multiple river 9 David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon (New York: Scribner, 1973), page 466. 10 Ibid., page 465. 11 Ibid., page 454. 12 Ibid., page 453. David G. Chandler Ph.D., “Napoleon, Operational Art, and the Jena Campaign,” in Historical Perspectives of the Operational Art, ed. Michael D. Krause and R. Cody Phillips (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 2007), page 37. 13 14 David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon (New York: Scribner, 1973), page 468. 5 crossings. 15 This approach pushes Prussia back on Russian forces and loses sight of Austria. Maneuver from the south, attacking from Bamberg to Berlin incurs risk by separating the Grand Army in the Thüringen Wald, however there is an opportunity for speed and surprise in the square battalion formation. 16 Thereafter, the Grand Army can maneuver on a line between the Saale and Elbe Rivers between Leipzig and Dresden, separating the Prussian and Russian forces while maintaining influence on Austria. Elements of Operational Art Returning to the operational approach, the elements of operational art – end state, center of gravity, decisive points, lines of operations, operational reach, basing, tempo, phasing and transitions, culmination, and risk – are useful for further discussion of Napoleon’s plan for the Jena Campaign.17 Napoleon was clear in his desired end state – the Prussian Army defeated in a decisive battle, Prussia incorporated into the French Empire, the combat power of the Grand Army preserved, and the border pushed east through Prussia to the Russian frontier. By articulating and communicating his end state to his subordinate commanders and allies, Napoleon ensured unity of effort by his corps and encouraged disciplined initiative during exploitation and pursuit.18 Napoleon perceived the Prussian Army as the center of gravity – the source of power that enabled action for Prussia.19 However, this was one of Napoleon’s mistakes and illustrates the importance of an accurate assessment of the center of gravity. The Grand Army destroyed the Prussian Army, yet Prussia did not capitulate and the government would hold out for several 15 David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon (New York: Scribner, 1973), pages 40-41 16 Ibid., page 41 17 U.S. Army, ADRP 3-0, Unified Land Operations (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2011), page 4-3. 18 Ibid., page 4-3. 19 Ibid., page 4-3. 6 more months. Therefore, the Prussian government was arguably the center of gravity, with the destruction of the Prussian Army a decisive point along the way. Napoleon utilized both geographic lines of operations and decisive points to define the Jena Campaign. He described the line from Bamberg to Berlin as the directional orientation that linked the base of operations with the objective.20 Along this line, the Grand Army would move on three roads through Thüringen Wald. Along this line, the area past the Thüringen Wald between Hof and Saalfield marked the location where the Grand Army would converge. Therefore, this area was a decisive point, giving Napoleon a marked advantage over the Prussian Army.21 Napoleon also identified the terrain between Leipzig and Dresden as a decisive point. This was the central location between Prussian and Russian forces, which threatened Berlin. Tempo was a key element of Napoleon’s campaign plan. The square battalion, competent subordinate commanders, and inadequate Prussian leadership enabled the Grand Army to dictate the speed of operations.22 Thus, as the Grand Army transitioned from the approach march to the main battle, Napoleon overwhelmed the Prussian Army’s ability to counter friendly actions by committing additional corps to the battle at Jena. While badly outnumbered at Auerstadt, Davout’s corps dictated the tempo to Brunswick’s larger force, leading to victory. Operating from a base centered on Bamberg, Napoleon understood that his supply train limited his operational reach. Therefore, he realized that he would culminate prior to Berlin, more than likely around Leipzig. In order to extend his operational reach and culmination point, Napoleon either needed to bring his supply forward of the Thüringen Wald or cut ties with Bamberg and rely on Mainz. Either of these actions would suffice until the Grand Army could gain Magdeburg or Wittenberg and establish new bases. 20 U.S. Army, ADRP 3-0, Unified Land Operations (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2011), page 4-5. 21 Ibid., page 4-4. 22 Ibid., page 4-7. 7 Phases and transitions allowed Napoleon to organize forces in time, space, and purpose to accomplish key tasks inherent to each phase.23 In particular, the approach march and main battle allowed Napoleon to maximize combat power first to find the Prussian Army, then to defeat them with overwhelming combat power. Based on previously issued orders and geographic decisive points, subordinate commanders understood when to transition and what actions to take. The only apparent mistake was the inaction of Bernadotte’s corps between Jena and Auerstadt. Finally, Napoleon considered risk and weighed it against opportunity. The advance on the chosen line of operation posed risk in separating the Grand Army while negotiating difficult terrain. However, the opportunity outweighed the risk. On this line, Napoleon surprised the Prussian Army, gained the central position, and kept watch on the Austrians. To mitigate the risk inherent to the operation, Napoleon employed the square battalion formation to provide mutual support on the approach march in the face of uncertain enemy location. Conclusion In closing, the Jena Campaign did not unfold as Napoleon envisioned. Napoleon made no fewer than six errors in judgment, yet the campaign was still successful in terms of military victory.24 While the armies of the great powers were all of similar capabilities in the early nineteenth century, the operational art exercised by Napoleon was superior to all contemporary equivalents.25 The operational art perfected by Napoleon allowed France to dominate Europe until the fateful Russian campaign of 1812. 23 U.S. Army, ADRP 3-0, Unified Land Operations (Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2011), page 4-3. David G. Chandler Ph.D., “Napoleon, Operational Art, and the Jena Campaign,” in Historical Perspectives of the Operational Art, ed. Michael D. Krause and R. Cody Phillips (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 2007), page 64. 24 25 Ibid., page 65. 8 Bibliography Army, U.S. ADP 3-0, Unified Land Operations. Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2011. Army, U.S. ADRP 3-0, Unified Land Operations. Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2012. Army, U.S. ADRP 5-0, Unified Land Operations. Washington, DC: Headquarters, Department of the Army, 2012. Chandler, David G. “Napoleon, Operational Art, and the Jena Campaign.” In Historical Perspectives of the Operational Art, edited by Michael D. Krause and R. Cody Phillips, 27-68. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 2007. Chandler, David G. The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Scribner, 1973. 9