Flatiron Building Paper

advertisement

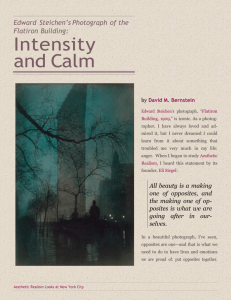

Andrew Smeathers Prof. Geib HST 212 March 19th 2013 The Historic Flatiron (Fuller) Building, NYC The Flatiron Building, formerly known as the Fuller Building, was a groundbreaking skyscraper that symbolized the growth and power of a young and ever changing United States. Located at 175 Fifth Avenue in the borough of Manhattan, New York City, the Flatiron Building was completed in 1902 and stands 285 feet tall, with twenty two stories. Upon completion the building was not only one of the tallest buildings in the city, but one of the tallest in the world. The Flatiron Building was known for more than just its impressive height. The building was made with a unique architectural design, which resembled a vertical Renaissance palazzo. The Flatiron Building, while a major feat of engineering during the early 20th century, meant more to a country than anyone could have imagined. (History). Amos Eno, who was the owner of many buildings in Manhattan, owned the land that the Flatiron Building would eventually be built upon. Many years before the bright lights of Times Square in New York City, New Yorkers went to the site of the future Flatiron Building to receive breaking news from the New York Times. The New York Times used four of the seven stories of the former Cumberland Apartments to project news bulletins and election information on the side of the building. Tens of thousands of people would gather in Madison Square, which is located adjacent to the building, to see the latest presidential poll results. (Robertto) When Amos Eno passed away the land known as Eno’s flatiron, due to its resemblance to a flatiron, was put up for sale. The land went through many different owners before the Cumberland Realty Company, part of the Fuller Company, purchased the land for around two million dollars. The Fuller Company was the first, true, general contractor that dealt with all aspects of building construction except design. (History). The company was also known for building some of the first skyscrapers in America. Harry S. Black, who was CEO of the Fuller Company, wanted to use this new plot of land to build a new headquarters building for local companies. Black reached out to the Chicago architect Daniel Burnham to design the new skyscraper. The building was to be the first skyscraper north of 14th street in New York, and be named the Fuller Building after George A. Fuller who founded the Fuller Company and was known as the, “Father of the skyscraper.” The name however would not last long due to the community’s persistence to call the building and the surrounding area the Flatiron district. The Flatiron Building was designed by, Chicago’s, Daniel Burnham as a vertical Renaissance palazzo with Beaux-Arts styling. Beaux-Arts architecture is dependent on sculptural decorating along conservative modern lines, employing French and Italian Baroque and Rococo formulas combined with an impressionistic finish and realism. Unlike many of New York’s early skyscrapers, which took the form of towers arising from a lower, blockier mass, the Flatiron building epitomizes the Chicago school conception with its Greek columns and limestone and glazed terra-cotta façade. The unusual shape of the Flatiron Building was due to the land it was placed on. The building is shaped to an acute angle of about 25 degrees. At the vertex, the triangular tower is only six and a half feet wide. The Fuller Company decided to use a steel skeleton for the interior of the building. This way of engineering allowed them to build higher than surrounding building with ease. (History). When construction on the building began, locals took an immediate interest, placing bets on how far the debris would spread when the wind knocked it down. This presumed susceptibility to damage had also given it the nickname Burnham's Folly. But thanks to the steel bracing designed by engineer Corydon Purdy, which enabled the building to withstand four times the amount of wind force it could be expected to ever feel, there was no possibility that the wind would knock over the Flatiron Building. Nevertheless, the wind was a factor in the public attention the building received. Due to the geography of the site, with Broadway on one side, Fifth Avenue on the other, and the open expanse of Madison Square and the park in front of it, the wind currents around the building could be treacherous. Wind from the north would split around the building, downdrafts from above and updrafts from the vaulted area under the street would combine to make the wind unpredictable. This is said to have given rise to the phrase “23 skidoo”, from what policemen would shout at men who tried to get glimpses of women's dresses being blown up by the winds swirling around the building due to the strong downdrafts. (History). The Flatiron Building has become an icon representative of New York City, but the critical response to it at the time was not completely positive, and what praise it garnered was often for the cleverness of the engineering involved. Montgomery Schuyler, editor of Architectural Record said that its, "awkwardness [is] entirely undisguised, and without even an attempt to disguise them, if they have not even been aggravated by the treatment. ... The treatment of the tip is an additional and it seems wanton aggravation of the inherent awkwardness of the situation." He praised the surface of the building, and the detailing of the terra-cotta work, but criticized the practicality of the large number of windows in the building: "[The tenant] can, perhaps, find wall space within for one roll top desk without overlapping the windows, with light close in front of him and close behind him and close on one side of him. But suppose he needed a bookcase? Undoubtedly he has a highly eligible place from which to view processions. But for the transaction of business?” (Alexiou). However some looked at the Flatiron Building in a different light. Futurist H.G. Wells wrote in his 1906 book, The Future in America: a Search After Realities: “I found myself agape, admiring a skyscraper the prow of the Flatiron Building, to be particular, plowing up through the traffic of Broadway and Fifth Avenue in the afternoon light.” (Wells). The Flatiron was able to attract the attention of numerous artists. It was the subject of one of Edward Steichen’s atmospheric photographs, taken on a wet wintry late afternoon in 1904, as well as a memorable image by Alfred Stieglitz taken the year before. Stieglitz reflected on the dynamic symbolism of the building, noting that it "...appeared to be moving toward [him] like the bow of a monster ocean steamer – a picture of a new America still in the making," and remarked that what the Parthenon was to Athens, the Flatiron was to New York. (Burns). When Stieglitz' photograph was published in Camera Work, his friend Sadakichi Hartmann, a writer, painter and photographer, accompanied it with an essay on the building: "A curious creation, no doubt, but can it be called beautiful? Beauty is a very abstract idea ... Why should the time not arrive when the majority without hesitation will pronounce the 'Flatiron a thing of beauty?" (Alexiou). As Alfred Stieglitz stated, the Flatiron Building was a picture of a new America still in the making. As the United States was expanding its empire to the west and to the world, the east coast was beginning its skyscraper movement. While the Flatiron Building was not the first skyscraper, its unique shape and architectural design correspond with the development of America. The birth of the skyscraper showed a new opportunity for citizens as they looked on in astonishment to the towering buildings. The Flatiron Building is an American icon that is still respected today. The building has been placed on the New York City Landmarks, National Register of Historic Places, and National Historic Landmarks registries. The Flatiron Building will continue to look over Broadway Street and Fifth Avenue for years to come, inspiring people for decades. Works Cited Alexiou. "The Fuller Building." Architectural Record Oct. 1902: 125-26. Web. 18 Mar. 2013. Burns, Ric, James Sanders, and Lisa Ades. New York: An Illustrated History. New York: Knopf, 1999. 233. Print. History. "Flatiron Building." History.com. A&E Television Networks, n.d. Web. 18 Mar. 2013. Robertto, John. "The Flatiron Building." The Flatiron Building. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Mar. 2013. Wells, H. G. The Future in America: A Search after Realities. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1906. N. pag. Print.