Diagnosis and Management of Osteoporotic Fractures

advertisement

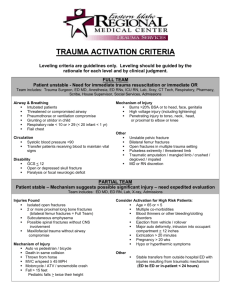

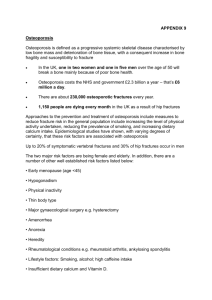

Epidemiology, Diagnosis Prevention and Management of Osteoporotic Fractures Kenneth A. Egol, MD NYU-Hospital For Joint Diseases Created March 2004; Revised February 2010 Background • Osteoporosis -- a decreased bone density with normal bone mineralization – WHO Definition (2010)1 • Bone Mineral Density ≥2.5 SD’s below the mean seen in young normal subjects – Incidence increases with age 2 • 30% of white women (age 50-70) are osteoporotic • By the age of 80, 70% are osteoporotic 1 2 Source: www.nof.org/professionals/WHO_Osteoporosis_Summary.pdf International Osteoporosis Center: Facts and Statistics Background • Risk factors for osteoporosis – – – – – – – Increasing age Female sex Race: Caucasian, Asian Sedentary lifestyle Multiple births Excessive alcohol use Tobacco use Background • Senile osteoporosis common – Some degree of osteopenia is found in virtually all healthy elderly patients • Treatable causes should be investigated – – – – – – Nutritional deficiency Malabsorption syndromes (e.g., Celiac Disease, IBD) Endocrine abnormalities (e.g., hyperparathyroidism) Cushing’s Disease Tumors/malignancy (e.g., Multiple Myeloma) Medications (e.g., corticosteroids) Background • The incidence of osteoporotic fractures is increasing – Estimated that half of all women and one-third of all men will sustain a fragility fracture during their lifetime • By 2050 6.3 million hip fractures will occur globally • Costs for osteoporosis-related fractures expected to increase from $19 billion in 2005 $25.3 billion in 2025. Image courtesy of International Osteoporosis Foundation Background • The most common fractures in the elderly osteoporotic patient include: – Hip Fractures • Femoral neck fractures • Intertrochanteric fractures • Subtrochanteric fractures – – – – Ankle fractures Proximal humerus fracture Distal radius fractures Image courtesy of International Osteoporosis Foundation Vertebral compression fractures Background • Fractures in the elderly osteoporotic patient represent a challenge to the orthopaedic surgeon • The goal of treatment is to restore the pre-injury level of function • Fracture can render an elderly patient unable to function independently -requiring institutionalized care Background • Osteopenia complicates both fracture treatment and healing • Internal fixation compromised – Poor screw purchase – Increased risk of screw pull out – Augmentation with methylmethacrylate has been advocated • Increased risk of non-union – Bone augmentation (bone graft, substitutes) may be indicated Pre-injury Status • Medical History • Cognitive History • Functional History – Ambulatory status • • • • Community Ambulator Household Ambulator Non-Functional Ambulator Non-Ambulator – Living arrangements Pre-injury Status • Systemic disease – Pre-existing cardiac and pulmonary disease is common in the elderly – Diminishes patients ability to tolerate prolonged recumbency – Diabetes increases wound complications and infection – May delay fracture union Pre-injury Status • American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Classification – ASA I- normal healthy – ASA II- mild systemic disease – ASA III- Severe systemic disease, not incapacitating – ASA IV- severe incapacitating disease – ASA V- moribund patient Pre-injury Status • Cognitive Status – Critical to outcome – Conditions may render patient unable to participate in rehabilitation • • • • Alzheimer’s CVA Parkinson's Senile dementia FRAX WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool • Estimates the 10-year patient-specific absolute fracture risk – Hip – Major osteoporotic (spine, forearm, hip or shoulder) • Developed by WHO to evaluate fracture risk of patients from epidemiological data from USA, Europe, Australia and Japan • Integrates clinical risk factors as well as BMD (femoral neck) • Incorporated into NOF treatment guidelines and other country-specific recommendations • Restricted to untreated patients Updated NOF Clinician’s Guide Incorporation of WHO Algorithm Previous NOF Guide (2003) Initiate treatment in PM women with: •T-score ≤-2.0 with no risk factors •T-score <-1.5 with ≥1 risk factors •Hip or vertebral fracture New NOF Guide (2008) Initiate Treatment in PM women and men age ≥50 with: •Hip or vertebral fracture •Other prior fracture and low bone mass (T-score -1.0 to -2.5) •T-score <-2.5 (2º causes excl.) •Low bone mass and 2º causes associated with high risk of fracture •Low bone mass AND 10-yr hip fracture probability ≥3% or 10-yr major OP-related fracture probability of ≥20% Hip Fractures • General principles – Most common fragility fracture – With the aging of the American population the incidence of hip fractures is projected to increase from 250,000 in 1990 to 650,000 by 2040 – Cost approximately $8.7 billion annually – 20% higher incidence in urban areas 1 – 15% lifetime risk for white females who live to age 80 1 1 International Osteoporosis Center: Facts and Statistics Hip Fractures • Epidemiology – Incidence increases after age 50 – Female: male ratio is 2:1 – Femoral neck and intertrochanteric fractures seen with equal frequency Image courtesy of International Osteoporosis Foundation Hip Fractures • Radiographic evaluation – Anterior-posterior view – Cross table lateral – Internal rotation view will help delineate fracture pattern Hip Fractures • Other imaging modalities – Occult hip fracture • Technetium bone scanning is a sensitive indicator, but may take 2-3 days to become positive • Magnetic resonance imaging has been shown to be as sensitive as bone scanning and can be reliably performed within 24 hours Hip Fractures • Management – Prompt operative stabilization • Operative delay of > 24-48 hours increases one-year mortality rates • However, important to balance medical optimization and expeditious fixation – Early mobilization • Decrease incidence of decubiti, UTI, atelectasis/respiratory infections – DVT prophylaxis Hip Fractures • Outcomes – Fracture related outcomes • Healing • Quality of reduction – Functional outcomes • Ambulatory ability • Mortality (25% at one year for age > 50) • Return to pre-fracture activities of daily living Hip Fractures • Femoral neck fractures – Intracapsular location – Vascular Supply • Primary blood supply to the femoral head is the deep branch of the medial femoral circumflex artery • Medial and lateral circumflex vessels anastomose at the base of the neck • Blood supply predominately from ascending arteries (90%) • Artery of ligamentum teres (10%) Hip Fractures • Femoral neck fractures • Treatment – Non-displaced/ valgus impacted fractures • Non-operative: 8-15% displacement rate • Operative with cannulated screws • Complications: Non-union (5%) and osteonecrosis (8%) Hip Fractures • Femoral neck fractures – Displaced fractures should be treated operatively – Treatment: Open vs. closed reduction and internal fixation • 30% non-union and 25%-30% osteonecrosis rate • Non-union requires reoperation 75% of the time while osteonecrosis leads to reoperation in 25% of cases Hip Fractures • Femoral neck fractures • Treatment: – Total Hip Arthroplasty • Now standard for younger elderly active patients – Hemiarthroplasty • Unipolar vs Bipolar • Can lead to acetabular erosion, dislocation, infection Hip Fractures • Femoral neck fractures • Treatment – Displaced fractures can be treated non operatively in certain situations • Demented, non-ambulatory patient – Mobilize early • Accept resulting non or malunion Hip Fractures • Intertrochanteric fractures – Extracapsular (well vascularized) – Region distal to the neck between the trochanters – Fracture patterns creating increased instability • • • • Calcar femorale involvement Posteromedial cortex involvement Lateral wall involvement Reverse obliquity pattern or subtrochanteric extension – Important muscular insertions Hip Fractures • Intertrochanteric fractures – Treatment • Generally treated surgically • Common implants include sliding hip screw and sliding cephalomedullary rod • These implants allows for controlled impaction upon weight bearing Hip Fractures • Intertrochanteric fractures – Treatment • Primary prosthetic replacement can be considered in select cases with significant comminution although fixation is much more common Hip Fractures • Subtrochanteric Fractures – Begin at or below the level of the lesser trochanter – Typically higher energy injuries seen in younger patients – Far less common in the elderly – Increasingly more common with long term use of bisphosphonates (Lenart et al. NEJM 2008) Hip Fractures • Subtrochanteric Fractures – Treatment • Intramedullary nail (high rates of union) • Plates and screws Ankle Fractures • Common injury in the elderly – Significant increase in the incidence and severity of ankle fractures over the last 20 years • Low energy injuries following twisting reflect the relative strength of the ligaments compared to osteopenic bone Ankle Fractures • Epidemiology – Finnish Study (Kannus et al) • Three-fold increase in the number of ankle fractures among patients older than 70 years between 1970 and 2000 • Increase in the more severe Lauge-Hansen SE-4 fracture – In the United States, ankle fractures have been reported to occur in as many as 8.3 per 1000 Medicare recipients • Figure that appears to be steadily rising. Ankle Fractures • Presentation – – – – Follows twisting of foot relative to lower tibia Patients present unable to bear weight Ecchymosis, deformity Careful neurovascular exam must be performed Ankle Fractures • Radiographic evaluation – Ankle trauma series includes: • AP • Lateral • Mortise – Examine entire length of the fibula Ankle Fractures • Treatment – Isolated, non-displaced malleolar fracture without evidence of disruption of syndesmotic ligaments treated non-operatively with full weight bearing – May utilize walking cast or cast brace Ankle Fractures • Treatment – Unstable fracture patterns with bimalleolar involvement, or unimalleolar fractures with talar displacement must be reduced – Closed treatment requires a long leg cast to control rotation • May be a burden to an elderly patient Ankle Fractures • Treatment – Irreducible fractures require open reduction and internal fixation – The skin over the ankle is thin and prone to complication – Await resolution of edema to achieve a tension free closure Ankle Fractures • Treatment – Fixation may be suboptimal due to osteopenia • May have to alter standard operative techniques • Locked plates, multiple syndesmotic screws – Reports in literature mixed • Early studies showed no difference in operative vs non-op treatment -- with operative groups having higher complication rates • More recent studies show improved outcomes in operatively treated group – Goal is return to pre-injury functional status Proximal Humerus • Background – – – – – Very common fracture seen in geriatric populations 112/100,000 in men 439/100,000 in women Result of low energy trauma Goal is to restore pain free range of shoulder motion Proximal Humerus • Epidemiology – Data suggest that fracture of proximal humerus is the 3rd most common fracture over age 65 – Incidence rises dramatically beyond the fifth decade in women – 76% of all proximal humerus fractures occur in patients older than 60 1 – Associated with • Frail females • Poor neuromuscular control • Decreased bone mineral density 1 International Osteoporosis Center: Facts and Statistics Proximal Humerus • Background – Articulates with the glenoid portion of the scapula to form the shoulder joint – Four parts – Combination of bony, muscular, capsular and ligamentous structures maintains shoulder stability – Status of the rotator cuff is key Proximal Humerus • Radiographic evaluation – – – – AP Scapula Y Axillary CT scan can be helpful Proximal Humerus • Treatment – Minimally displaced (one part fractures) usually stabilized by surrounding soft tissues • Non operative: 91% good to excellent results Proximal Humerus • Treatment – Isolated lesser tuberosity fractures require operative fixation only if the fragment contains a large articular portion or limits internal rotation – Isolated greater tuberosity associated with longitudinal cuff tears and require ORIF if significantly displaced Proximal Humerus • Treatment – Displaced surgical neck fractures can be treated closed by reduction under anesthesia with Xray guidance • Anatomic neck fractures are rare but have a high rate of osteonecrosis – If acceptable closed reduction is not attained, open reduction should be undertaken Proximal Humerus • Treatment – Closed treatment of 3 and 4 part fractures have yielded poor results – Failure of fixation is a problem in osteopenic bone • Locked plating versus prosthetic replacement Proximal Humerus • Treatment – Regardless of treatment all require prolonged, supervised rehabilitation program – Poor results are associated with rotator cuff tears, malunion, nonunion – Prosthetic replacement can be expected to result in relatively pain free shoulders – Functional recovery and ROM variable Distal Radius • Background – Very common fracture in the elderly – Result from low energy injuries – Incidence increases with age, particularly in women – Associated with dementia, poor eyesight and a decrease in coordination Distal Radius • Epidemiology – Increasing in incidence • Especially in women – – – – – 125/100,000 Peak incidence in females 60-70 Lifetime risk is 15% Most frequent cause: fall on outstretched arm Decreased bone mineral density is a factor Distal Radius • Radiographic evaluation – – – – PA Lateral Oblique Contralateral wrist • Important to evaluate deformity, ulnar variance Distal Radius • Treatment – Non-displaced fractures may be immobilized for 6-8 weeks – Metacarpal-phalangeal and interphalangeal joint motion must be started early Distal Radius • Treatment – Displaced fractures should be reduced with restoration of radial length, inclination and tilt • Usually accomplished with longitudinal traction under hematoma block – If satisfactory reduction is obtained, treatment in a long arm or short arm cast is undertaken • No statistical difference in method – Weekly radiographs are required Distal Radius • Treatment – If acceptable reduction not obtained – Regional or general anesthesia – Methods • ORIF • Closed reduction and percutaneous pinning with external fixation Distal Radius • Treatment – Results are variable and depend on fracture type and reduction achieved – Minimally displaced and fractures in which a stable reduction has been achieved result in good functional outcomes Distal Radius • Treatment – Displaced fractures treated surgically produce good to excellent results 70-90% – Functional limits include pain, stiffness and decreased grip Vertebral Compression Fractures • Background – Nearly all post-menopausal women over age 70 have sustained a vertebral compression fracture – Usually occur between T8 and L2 – Kyphosis and scoliosis may develop • Markers for osteoporosis Vertebral Compression Fractures • Epidemiology – Estimated that only 1/3 of vertebral fractures come to clinical attention – highly underreported – Prevalence similar for men and women age 60-70 – 117/100,000 – A 50 year old white woman has a 16% lifetime risk of experiencing a vertebral fracture Image courtesy of International Osteoporosis Foundation Vertebral Compression Fractures • Background – Present with acute back pain – Tender to palpation – Neurologic deficit is rare • Patterns – Biconcave (upper lumbar) – Anterior wedge (thoracic) – Symmetric compression (T-L junction) Vertebral Compression Fractures • Radiographic evaluation – AP and lateral radiographs of the spine – Symptomatic vertebrae 1/3 height of adjacent – Bone scan can differentiate old from new fractures Vertebral Compression Fractures • Treatment – Simple osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures are treated non-operatively and symptomatically – Prolonged bedrest should be avoided – Progressive ambulation should be started early – Back exercises should be started after a few weeks Vertebral Compression Fractures • Treatment – A corset may be helpful – Most fractures heal uneventfully – Kyphoplasty an option Prevention • Strategies focus on controlling factors that predispose to recurrent fracture – Consider bone mineral density test – Rule out secondary causes of osteoporosis – Initiate and monitor therapy, or refer • Fall prevention Prevention • Multidisciplinary programs – – – – Medical adjustment Behavior modification Exercise classes Controversial Prevention and Treatment of Bone Fragility • Well established link between decreasing bone mass and risk of fracture • Prevention/treatment options Bisphosphonates -Alendronate (Fosamax ®) -Risedronate (Actonel ®) -Ibandronate (Boniva ®) -Zolendronate (Aclasta ®) SERMs - Raloxifene (Evista ®) Hormone Therapy/Replacement - Estrogen/progestin Other - Calcitonin Stimulators of bone formation - rh-PTH (Forteo ®) Prevention and Treatment of Bone Fragility • Estrogen/progestin – FDA approved for prevention, not treatment of osteoporosis – 3-5% bone loss/year with menopause – Unopposed or combined therapy has been shown to reduce hip fracture incidence in women aged 65-74 by 40-60% (Henderson et al. 1988) – However, the Women’s Health Initiative (2009) concluded reduction in hip fracture not offset by increased risk of breast & endometrial cancers, thromboembolism, dementia, and coronary heart disease Prevention and Treatment of Bone Fragility • Calcium/Vitamin D Supplementation – Recommended for most men and women >50 years • Calcium – Age <50 -- 1,000 mg/day – Age >50 -- 1,200 mg/day • Vitamin D – Age < 50 – 400-800 IU/day – Age >50 – 800-1000 IU/day • Combining Vitamin D and calcium supplementation has been shown to increase bone mineral density and reduce the risk of fracture Prevention and Treatment of Bone Fragility • Calcitonin – Inhibits bone resorption by inhibiting osteoclast activity – Approved for treatment of osteoporosis in women who have been post-menopausal for > 5 years • Daily intranasal spray of 200 IU – Trial demonstrated 33% reduction of vertebral compression fractures with daily therapy (Chesnut Am J Med 2000) – Calcitonin is indicated for no longer than 24 months in the United States to prevent “resistance” Prevention and Treatment of Bone Fragility • Bisphosphonates – Inhibits bone resorption by reducing osteoclast recruitment and activity – Bone formed while on bisphosphonate therapy is histologically normal • Strongest evidence for rapid fracture risk reduction – Decreasing the incidence of both vertebral and nonvertebral fractures • Recent evidence of increased risk of subtrochanteric insufficiency fractures with long term use (Lenart et al. NEJM 2008) Prevention and Treatment of Bone Fragility • Alendronate – Shown to increase the bone density in femoral neck in post menopausal women with osteoporosis (Lieberman et al. NEJM 1995) – Fracture Intervention Trial (FIT) demonstrated daily Fosamax for 3 years significantly reduced the risk of vertebral fracture by 47% and of hip fracture by 51% in women with low BMD and previous vertebral fracture (Black et al. Lancet 1996) – Recently associated with lateral cortical stress fractures following long term use. Prevention and Treatment of Bone Fragility • Teriparatide (Forteo) – Recombinant formulation of parathyroid hormone – Stimulates the formation of new bone by increasing the number and activity of osteoblasts – Once daily subcutaneous injection of 20 g • Study of 1637 post-menopausal women – 65% reduction in the incidence of new vertebral fractures – 53% reduction in the incidence of new nonvertebral fractures Conclusions • Prevention is multifaceted: a fragility fracture is the strongest predictor of a future fracture • Cost containment is a joint effort between orthopaedists, primary care physicians, PT and social work • Functional outcome is maximized by early fixation and mobilization in operative cases • With the increasing population of elderly, orthopaedic surgeons must be proactive in secondary prevention of fragility fractures If you would like to volunteer as an author for the Resident Slide Project or recommend updates to any of the following slides, please send an e-mail to ota@ota.org Return to General/Principles Index Recommended Reading • • • • • • • Turner CH. Biomechanics of bone: determinants of skeletal fragility and bone quality. Osteoporos Int 13:97–104, 2002. Kleerekoper M. Osteoporosis prevention and therapy: preserving and building strength through bone quality. Osteoporos Int 17:1707–1715, 2006. www.nof.org/professionals/WHO_Osteoporosis_Summary.pdf Haidukewych GJ, et al. Reverse obliquity fractures of the intertrochanteric region of the femur JBJS 83A: 643-50, 2001. Koval KJ, et al. Postoperative weight-bearing after a fracture of the femoral neck or an intertrochanteric fracture. JBJS 80A: 352-6, 1998. Baumgaertner MR, et al. The value of the tip-apex distance in predicting failure of fixation of peritrochanteric fractures of the hip JBJS 77A:1058-1064, 1995. Chan SS, et al. Subtrochanteric femoral fractures in patients receiving long-term alendronate therapy: imaging features. AJR 2010; 194:1581–1586