File - The Portrayal of Arabs in American Sitcoms Post 9/11

advertisement

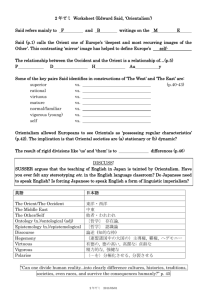

Miller 1 Chris Miller Mark Kehren Historical Geography 18 May 2011 Literature Analysis “Most definitions of popular culture involve mass consumption-that is, popular culture is available to most people in a society relatively easily”.1 This is how Jason Dittmer defines pop culture and he goes on to state how popular culture can take a variety of forms from sporting events to comic books. Popular culture can be used a variety of ways with one being that culture is used to create and to spread a certain meaning or message. This use of popular culture places a much more significant meaning to it than most would be willing to give. Many view pop culture as simply a form of entertainment and nothing more. While it is true that pop culture is used to “kill time” and for entertainment purposes, there can be, and are, much more significant meanings to a lot of pop culture. It is used as a way to formulate opinions and spread ideologies. This gives pop culture and those who are the creators of it a form of power over the consumers. We can see this idea is quite strong in the Marxist scholars of the Frankfurt School: Here the term “consumer” takes on something of a literal meaning in that consumers of popular culture are denied any agency-the effects of the popular culture are encoded in the moment of production, leaving consumers in the 1 Jason Dittmer, Popular Culture, Geopolitics, & Identity (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2010). Miller 2 role of zombies, internalizing the preferred meanings of the popular culture with which they are presented.2 This quote the Dittmer uses to explain the Marxist scholars truly shows that popular culture is not simply a form of entertainment. There is a meaning behind why producers create pop culture the way that they do. Pop culture has power to it and those that are in charge of how it is dispersed to the consumers are in control, which is difficult to argue. We, as consumers, must purchase what the producers give us. If we want something that is not offered we cannot simply walk up to the producers and tell them how they should create the show we want to watch or write the novel we would like to read. They are the ones who are in charge of this and we cannot control that. One could argue that as the consumer we have the opportunity to purchase certain items to get our point across to the creators of those items and, if they want to continue their business they will pay attention to where we are spending our money, but there is a lot of truth to the statement that we are at the hands of the producers and are forced to take in whatever message they are supplying us with. Whether one believes that consumers are at the hands of the producers, one argument about popular culture that is difficult to disagree with is that popular culture has messages within it that are being spread to the consumers in hopes that they will be accepted. When writing on the affects of pop culture in Sichaun, China, Li states that “popular culture, in the forms of stories, songs, and children’s primers, also played a crucial role by both shaping and expressing popular anti-imperialist attitudes”.3 We can see here that pop culture that is still very present in our present day United States were used to influence how those taking in the pop culture, most everyone in society, viewed imperialism and nationalism. In a study on the role of the mass media and stereotypes held of Russians and Easter Europeans by Americans, Ibroscheva was able to “…refine and further illuminate the modifying 2 Ibid. Danke Li, “Popular Culture in the Making of Anti-Imperialist and Nationalist Sentiments in Sichuan,” Modern China 30, no. 4 (October 1, 2004): 470-505. 3 Miller 3 relationship between public and individual perceptions of foreigners and the images used to depict them in the mass media”4 It can be seen from this quote that Ibroscheva was able to find a correlation between the portrayal of foreigners in the media and the subsequent affect it had on those who viewed it. An aspect of the mass media that has been extremely popular is that of television, and an aspect of television that is quite popular is that of sitcoms. However, television sitcoms are not immune to the influence of their creators. We hear people making claims such as the fact that sitcoms are meant to convey “the underlying assumptions of corporate culture that have come to dominate American society…”5 We also see this idea portrayed by those that are producing the sitcoms such as Gene Reynolds discussing the show “M*A*S*H”; “…the show was a form of political activism designed to discourage American participation in the Vietnam war”.6 We can see from these two quotes that the scholars who made these claims differ on the purpose of the American sitcom, but they both believe that there is more to the show than simple entertainment. There are messages that producers want to get across to their viewer and sitcoms are embedded with messages for the viewer to pick up on. The article goes on to state, however, that we as the view have the option to interpret the meaning of the show in whatever way we choose. This means that while the producer or “M*A*S*H” may have been hoping that his viewers internalize his idea that the war in Vietnam was wrong, and that they should not join the fighting, it is extremely possible that the show interested some people in war and cause them to join. We can see situations such as this daily in our society. Quite often to people say something to a person, only to have them interpret it differently than how it was originally meant. This goes back to the question we were dealing with earlier of whether or not the viewers have control over 4 Elza Ibroscheva, “Is There Still an Evil Empire? The Role of the Mass Media in Depicting Stereotypes of Russians and Eastern Europeans,” Global Media Journal 1, no. 1 (Fall 2002). 5 Charles McGovern, “Review: [untitled],” The Journal of American History 81, no. 2 (1994): 783-784. 6 Ronald Berman, “Sitcoms,” Journal of Aesthetic Education 21, no. 1 (April 1, 1987): 5-19. Miller 4 what they are to internalize or toss aside. Although producers may have a certain message they want to get across, they truly have no power in whether they are successful or not. This topic of whether we have the power to control if we take in what is being portrayed by the media was summarized in a quote from Said that said “‘for years we heard Walter Cronkite say on television every night ‘That’s the way it is.’ The role of humanism is to say ‘No, that’s not the way it is’”.7 This quote from Said shows that he believes we do have power to form our own opinion. However, this is not as easy as it seems and I feel that in order to be able to say that “this is not how it is” we need to know why these sitcoms, and pop culture in general, portray situations the way they do. Up to this point I have been simply discussing a variety of ways that pop culture have affected the general public, but the way that I am focusing on in my presentation is that of the portrayal of Arabs in American sitcoms. While there are many methodologies that could be used to explain why Arabs are portrayed the way they are, I believe the Orientalism stands out as the dominate method to figure this out. Said argues that one of the main things that occur under this idea of Orientalism is that those who live in the Occident often group those from the Orient into a single category: So saturated with meanings, so overdetermined by history, religion, and politics are labels like “Arab” or “muslim” as subdivisions of “The Orient” that no one today can use them without some attention to the formidable polemical mediations that screen the objects, if they exist at all, that the labels designate.8 We can see from this quote that here, in the Occident, we have become so familiar with labeling those who are Arabs or Muslims as a single entity. We group them together as though they are one and 7 Jacqueline Brady, “Cultivating Critical Eyes: Teaching 9/11 through Video and Cinema,” Cinema Journal 43, no. 2 (January 1, 2004): 96-99. 8 Edward W. Said, “Orientalism Reconsidered,” Cultural Critique, no. 1 (October 1, 1985): 89-107. Miller 5 if one member of this group acts in a certain way, than we apply it to the rest of them. Said has met a lot of criticism when it comes to his ideology, but I feel that all we need to do is look at our society today and we will be able to see this grouping of all those that are from the Orient into a single category. The quote also exposes a major problem of this labeling and that is the point that it does not simply occur in a single situation. We are getting this idea that every Oriental is the same from our politics, religion, and history, and I would be willing to say from our pop culture as well. Said states that we do not stop at simply claiming that all Orientals are the same, however. Said proposes that we also make sure that we distinguish ourselves from them. He states that “the relatively common denominator between these three aspects of Orientalism is the line separating Occident from Orient…”9 We can see this separation in a variety of ways, but one of the most common is explained to us by Cainkar, “the special handling of Arabs at airports simply because of their names or looks reveals just how widely and unguidedly the net in the terrorist search is being cast.”10 This quote shows many aspects that are brought up in Orientalism. One can be the cementing of the idea that we group all of those from the Orient into a single category. Because those that attacked on 9/11 were Muslim, everyone who seems Muslim to us is now a threat. Simply based off of their name or skin color, we are willing, and I would argue eager, to group them into the same category as the terrorist from that day. We can also see the aspect of separating them from us. Not only are we grouping them all together with this action, we are showing everyone that they are different. It was “them” that attacked “us” and we need to stick together and make sure that they are kept separate. The article goes on to give many more examples of how we are separating the Orient from us, especially after 9/11, but even in the years before the attack. 9 Ibid. Louise Cainkar, “No Longer Invisible: Arab and Muslim Exclusion after September 11,” Middle East Report, no. 224 (October 1, 2002): 22-29. 10 Miller 6 One of the final aspects that can be seen in Orientalism is a fear that we in the Occident hold of those who are in the Orient. As mentioned above, we separate ourselves from those that are Oriental and because of this separation we do not allow ourselves to come to know and understand those from the Orient. Because of this we have a tendency to fear them. This fear, however, was taken to a new level after the September 11th attacks. I believe that this occurred because of the fact that we group all Orientals together and, after the attacks, we grouped them with the terrorist. “Although the immediacy of the morning’s panic had dissipated over five years, September 11 nonetheless ushered in a new era of fear in our country.”11 This quote very clearly describes the affect that the attacks of that day had on our country. We became fearful, understandably, of something that most of us had never feared before. Very few, if any, of us had ever experienced an attack on the United States such as that one and it brought about a new wave of fear. However, we took this fear and applied to those that we grouped together as Oriental. Although we had no logical reason to assume that every Arab or Muslim in the United States was a terrorist, we did as can be explained by Said’s Orientalism. 11 Laura M. Grow, “"Bound In to Saucy Doubts and Fears": Examining America's Culture of Fear,” The English Journal 96, no. 2 (November 1, 2006): 57-61. Miller 7 Works Cited Berman, Ronald. “Sitcoms.” Journal of Aesthetic Education 21, no. 1 (April 1, 1987): 5-19. Brady, Jacqueline. “Cultivating Critical Eyes: Teaching 9/11 through Video and Cinema.” Cinema Journal 43, no. 2 (January 1, 2004): 96-99. Cainkar, Louise. “No Longer Invisible: Arab and Muslim Exclusion after September 11.” Middle East Report, no. 224 (October 1, 2002): 22-29. Dittmer, Jason. Popular Culture, Geopolitics, & Identity. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2010. Grow, Laura M. “"Bound In to Saucy Doubts and Fears": Examining America's Culture of Fear.” The English Journal 96, no. 2 (November 1, 2006): 57-61. Ibroscheva, Elza. “Is There Still an Evil Empire? The Role of the Mass Media in Depicting Stereotypes of Russians and Eastern Europeans.” Global Media Journal 1, no. 1 (Fall 2002). Li, Danke. “Popular Culture in the Making of Anti-Imperialist and Nationalist Sentiments in Sichuan.” Modern China 30, no. 4 (October 1, 2004): 470-505. McGovern, Charles. “Review: [untitled].” The Journal of American History 81, no. 2 (1994): 783-784. Said, Edward W. “Orientalism Reconsidered.” Cultural Critique, no. 1 (October 1, 1985): 89-107.