Protecting All Children's Teeth: Fluoride

advertisement

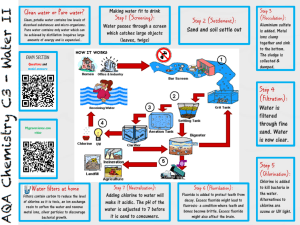

Protecting All Children’s Teeth Fluoride 1 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Introduction Used with permission from Lisa Rodriguez Fluoride plays an important role in the prevention of dental caries. The primary mechanism of action of fluoride in preventing dental caries is topical. Fluoride acts in the following ways to prevent dental caries: 1. It enhances remineralization of the tooth enamel. This is the most important effect of fluoride in caries prevention. 2. It inhibits demineralization of the tooth enamel. 3. It makes cariogenic bacteria less able to produce acid from carbohydrates. 2 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Learner Objectives Used with permission from Lisa Rodriguez Upon completion of this presentation, participants will be able to: 3 State the 3 mechanisms of action of fluoride in dental caries prevention Summarize the available sources of fluoride and their relative benefits List strategies to minimize the development of fluorosis Discuss the fluoride supplementation guidelines Recognize the various forms of fluorosis and recall their prevalence www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Fluoride Facts Fluoride has been available in the United States since the mid 1940’s. In 2008, 64.3% of the population served by public water systems received optimally fluoridated water. Public water fluoridation practice varies by city and state. Water fluoridation was recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as one of the 10 greatest public health achievements of the 20th century. 4 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Fluoride Facts, continued There is strong evidence* that community water fluoridation is effective in preventing dental caries. In 2011, the U.S Dept of Health and Human Services proposed that community water systems adjust the concentration of fluoride in drinking water to 0.7 mg/L ppm (change from 0.7-1.2 mg/L). 5 This proposal has not been finalized. Water filters may alter the fluoride content of community water. Activated charcoal filters and cellulose filters have a negligible effect Reverse osmosis filters and water distillation remove almost all fluoride from water www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Sources of Systemic Fluoride Exposure Fluoride can be ingested through: 6 Drinking water (naturally occurring or water system additive) Other beverages Foods Toothpaste Fluoride dietary supplements www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Bottled Water No one source exists to tell consumers the fluoride content in bottled waters. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not require that fluoride content be listed on the labels of bottled waters. It is reasonable to assume that children whose only source of water is bottled are not receiving optimal amounts of fluoride from that source. 7 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Commercial Beverages and Foods Many foods and beverages are made with community fluoridated water, so may contain fluoride. Foods such as seafood and certain teas can also have a naturally high fluoride content. This must all be taken into account when determining daily fluoride intake. 8 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Infant Nutrition Human breast milk contains almost no fluoride, even when the nursing mother drinks fluoridated water. Used with permission from Kathleen Marinelli, MD 9 Powdered infant formula contains little or no fluoride, unless mixed with fluoridated water. The amount of fluoride ingested will depend on the volume of fluoridated water mixed with the formula. www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Toothpaste Toothpaste’s effects are mainly topical, but some toothpaste is swallowed by children and results in systemic fluoride exposure. Strategies to Minimize Toothpaste Ingestion Limit the amount of toothpaste on the toothbrush Discourage children from swallowing toothpaste Encourage spitting of toothpaste Supervise brushing until spitting can be ensured 10 Used with permission from Norman Tinanoff, DDS www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Topical Sources of Fluoride Following are the most common forms of topical fluoride: 11 Toothpaste Fluoride mouthrinses Fluoride gels Fluoride varnish www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Toothpaste Toothpaste is the most recognizable source of topical fluoride. The addition of fluoride to toothpaste began in the 1950s. Used with permission from Rocio B. Quinonez, DMD, MS, MPH; Associate Professor Department of Pediatric Dentistry, School of Dentistry University of North Carolina Brushing with fluoridated toothpaste is associated with a 24% reduction in decayed, missing, and filled tooth surfaces. The CDC concluded that the quality of evidence for fluoridated toothpaste in reduction of caries is grade 1. Strength of recommendation is A for use in all persons. 12 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Toothpaste Guidelines The American Dental Association (ADA), American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD), and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) have all published the following recommendations: • • Suggest a “smear” or “grain of rice” amount of toothpaste starting at tooth emergence for all children. For children ages 3 to 6, recommend a “pea-sized” amount of fluoridated toothpaste. Toothpaste recommendations are no longer “risk-based”. 13 http://www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Toothpaste Amounts “Smear” “Pea-sized” 14 Fluoride Mouthrinses Mouthrinses containing fluoride are recommended in a “swish and spit” manner for children at least age 6. Mouthrinses are available over the counter. • • Daily use of a 0.05% sodium fluoride rinse may benefit children over 6 years who are at high risk for dental caries No additional benefit shown beyond daily fluoridated toothpaste use for children at low risk for caries The CDC concluded that quality of evidence for fluoride mouthrinses is Grade 1. Strength of recommendation is A with targeted effort at populations at high risk for dental caries. 15 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Fluoride Gels Fluoride gels are professionally applied or prescribed for home use under professional supervision. They are typically recommended for use twice per year. The CDC concluded that the quality of evidence for using fluoride gel to prevent and control dental caries in children is Grade 1. Strength of recommendation is A, with targeted effort at populations at high risk for caries. 16 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Fluoride Varnish Varnish is a professionally applied, sticky resin of highly concentrated fluoride (up to 22,600 ppm). Used with permission from Suzanne Boulter, MD In the United States, fluoride varnish has been approved by the FDA for use as a cavity liner and root desensitizer, but not specifically as an anti-caries agent. For caries prevention, fluoride varnish is an “off label” product. 17 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Fluoride Varnish Application frequency for fluoride varnish ranges from 2 to 6 times per year. The use of fluoride varnish leads to a 33% reduction in decayed, missing, and filled tooth surfaces in the primary teeth and a 46% reduction in the permanent teeth. Used with permission from Ian VanDinther 18 The CDC concluded that the quality of evidence for using fluoride varnish to prevent and control dental caries in children is Grade 1. Strength of recommendation is A, with targeted effort at populations at high risk for dental caries. Fluoride Varnish The United States Preventive Services Taskforce (USPSTF) in 2014 recommended that primary care clinicians apply fluoride varnish to the teeth of all infants and children, starting with the appearance of the first primary tooth through age 5, at least every 6 months. • • Recommendation applies to ALL children; no longer a risk-based recommendation Assigned a “B” grade recommendation AAP recommends that all children ages 5 and under should receive a professional fluoride treatment at least every 6 months in the primary care medical home. 19 Higher risk children should receive fluoride varnish application every 3 months. http://www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Community Water Fluoridation The goal of community water fluoridation is to maximize dental caries prevention while minimizing the frequency of enamel fluorosis. In January 2011, the US Department of Health and Human Services proposed 0.7 ppm be considered the optimal fluoride concentration in drinking water. Because there is geographic variability in community water fluoridation, it is important to know fluoride content of the water children consume. 20 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Water Fluoridation The US Environmental Protection Agency requires that all community water supply systems provide customers an annual report on the quality of water, including fluoride concentration. Families or providers can contact the local water authority for this information. Used with permission from iSTOCK Fluoride content of a town’s water can also be determined by accessing CDC’s My Water's Fluoride Web site. 21 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Well Water Wide variations in the natural fluoride concentration of well water sources exist. Private wells should be tested for fluoride concentration before prescribing supplements. Testing can be done through local and state public health departments or through private laboratories. 22 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Fluoride Dietary Supplementation When access to community water fluoridation is limited, fluoride can be supplemented in liquid, tablet, or lozenge form. Fluoride supplements require a prescription. Fluoride supplements should be prescribed only to children whose community water source has Suboptimal fluoride levels. 23 Used with permission from Content Visionary www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Supplementation Dosing Schedule The AAP, ADA, and AAPD have developed the following recommendations regarding fluoride supplementation: 1. All sources of fluoride must be considered, including primary drinking water, other sources of water, prescriptions from the dentist, fluoride mouthrinse in school, and fluoride varnish. 2. Children who have adequate access to (and are drinking) appropriately fluoridated community water should NOT be supplemented. 3. Children younger than 6 months and older than 16 years should NOT be supplemented. 24 Fluoride Supplements, continued CDC Quality of Evidence to Support the Use of Fluoride Supplements Children 6 years and younger: Grade II-3. Strength of recommendation of C with targeted effort at populations at high risk for dental caries. Children 6-16 years: Grade 1. Strength of recommendation of A with targeted effort at populations at high risk for dental caries. Pregnant women: Quality of evidence against providing fluoride supplementation to pregnant women to benefit their children is Grade 1. Strength of recommendation of E (good evidence to reject the use of the modality). 25 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Fluoride Supplements, continued The American Dental Association (ADA) and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) recommend fluoride supplements be prescribed only to children at high risk for caries. • Strength of recommendation: B 26 The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) in 2014 recommended fluoride supplementation be prescribed to ALL children older than 6 months whose primary water source is deficient in fluoride. • Strength of recommendation: B. • The AAP endorses the USPSTF recommendation to prescribe fluoride supplements to all children ages 6 months to 16 years who drink sub-optimally fluoridated water. Fluorosis Fluorosis is caused by an increased intake of fluoride during permanent tooth formation. Fluorosis Mild forms of fluorosis appear as chalk-like, lacy markings on the enamel. White opacity can be seen on more than 50% of the tooth in the moderate form of dental fluorosis. 27 Used with permission from Martha Ann Keels, DDS, PhD; Division Head of Duke Pediatric Dentistry, Duke Children's Hospital Severe fluorosis results in brown, pitted, brittle enamel. www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Fluorosis Dental fluorosis occurs during tooth development. Permanent teeth are more susceptible to fluorosis than primary teeth. Most critical ages of susceptibility are 0 to 6 years, especially between the ages of 15 and 30 months. Used with permission from Content Visionary 28 After 7 or 8 years of age, dental fluorosis cannot occur because the permanent teeth are fully developed, although not erupted. Prevalence of Fluorosis The prevalence of dental fluorosis has increased in the United States from 22.8% in 1986-1987 to 32% in 1999-2002. This can be attributed to the increased availability and ingestion of multiple sources of fluoride by young children, including: 29 Foods Beverages Toothpaste Other oral care products Dietary fluoride supplements www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Prevalence of Fluorosis, continued Some form of dental fluorosis is found in the following age groups*: 40% of US children ages 6-11 years 48% of 12- to 15-year-olds 42% of 16- to 19-year-olds Most of this fluorosis is mild and barely noticeable by non-dental health professionals. 30 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Prevalence of Fluorosis, continued Although the effects of dental fluorosis are mainly aesthetic, the increased prevalence mandates that health professionals be aware of all possible sources of fluoride before considering supplementation. 31 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Fluorosis and Toothpaste Ingestion of toothpaste increases the risk of enamel fluorosis. If fluoridated toothpaste is used, strategies to limit the amount swallowed include limiting the amount placed on the brush and observing the child as they brush. 32 Used with permission from Rocio B. Quinonez, DMD, MS, MPH; Associate Professor Department of Pediatric Dentistry, School of Dentistry University of North Carolina www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Fluorosis and Toothpaste According to the AAPD, the best way to minimize a child's risk for fluorosis is to limit the amount of toothpaste on the toothbrush. The AAP suggests a “smear” of toothpaste for children younger than 3 years of age and a "pea-sized" amount for children ages 3 and above. Used with permission from Michael SanFilippo 33 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Fluorosis and Toothpaste For children younger than 2, the CDC suggests the pediatrician consider fluoride levels in the community drinking water, other sources of fluoride, and factors likely to affect susceptibility to dental caries when weighing the risk and benefits of fluoride toothpaste. For children younger than 6, the CDC recommends that parents: 1. Limit tooth brushing to 2 times a day. 2. Apply less than a pea-sized amount of toothpaste to the brush. 3. Supervise tooth brushing and encourage children to spit out excess toothpaste. 4. Keep toothpaste out of the reach of young children to avoid accidental ingestion. 34 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Question #1 What is the most critical age of susceptibility to fluorosis of the permanent teeth? A. Between 0 and 15 months of age B. Between 15 and 30 months of age C. Between 30 and 45 months of age D. The risk of fluorosis in the permanent teeth is equal across all ages E. None of the above 35 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Answer What is the most critical age of susceptibility to fluorosis of the permanent teeth? A. Between 0 and 15 months of age B. Between 15 and 30 months of age C. Between 30 and 45 months of age D. The risk of fluorosis in the permanent teeth is equal across all ages E. None of the above 36 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Question #2 True or False? The most important mechanism of action of fluoride is a systemic effect. A. True B. False 37 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Answer True or False? The most important mechanism of action of fluoride is a systemic effect. A. True B. False 38 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Question #3 Which of the following is the most important function of fluoride in caries prevention? A. Fluoride enhances remineralization of tooth enamel B. Fluoride inhibits demineralization of tooth enamel C. Fluoride negatively affects the acid producing capabilities of cariogenic bacteria D. Fluoride displaces sugars from the surface of the teeth E. All of the above are equally important 39 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Answer Which of the following is the most important function of fluoride in caries prevention? A. Fluoride enhances remineralization of tooth enamel. B. Fluoride inhibits demineralization of tooth enamel. C. Fluoride negatively affects the acid producing capabilities of cariogenic bacteria. D. Fluoride displaces sugars from the surface of the teeth. E. All of the above are equally important. 40 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Question #4 True or False? Fluoride supplements should be prescribed for highrisk children whose community water source is optimal. A. True B. False 41 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Answer True or False? Fluoride supplements should be prescribed for highrisk children whose community water source is optimal. A. True B. False 42 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Question #5 Which of the following is a symptom of mild fluorosis? A. A white opacity on more than 50% of the tooth B. Dark spots on the teeth C. Brown, pitted, brittle enamel D. Chalk-like, lacy markings on the enamel E. None of the above 43 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact Answer Which of the following is a symptom of mild fluorosis? A. A white opacity on more than 50% of the tooth B. Dark spots on the teeth C. Brown, pitted, brittle enamel D. Chalk-like, lacy markings on the enamel E. None of the above 44 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 45 American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Infant Oral Health Care. Council on Clinical Affairs. Reference Manual 2011. 33(6): 124-128. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Policy on Early Childhood Caries (ECC): Classifications, Consequences, and Preventive Strategies. Pediatr Dent 2011, 33(6): 47-49. 3. American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. Guideline on Fluoride Therapy. Updated 2014. Reference Manual 36(6): 171-74. American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Professionally applied topical fluoride. Evidence-based clinical recommendations. JADA. August 1, 2006. 137(8): 1151-1159. American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Fluoride Toothpaste for Young Children. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(2):190-1. Berg J, Gerweck C, Hujoel PP, et al. Evidence-Based Clinical Recommendations Regarding Fluoride Intake from Reconstituted Infant Formula and Enamel Fluorosis. A Report of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. JAMA. January 2011 vol. 142(1): 79-87. www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact References, continued 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 46 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States. MMWR. 2001; 50(RR-14): 1-42. Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5014a1.htm. Accessed November 20, 2006. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for Dental caries, Dental sealants, Tooth Retention, Edentulism, and Enamel Fluorosis-United States, 19881994 and 1999-2002. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2005. 54(03);1-44. Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/ss5403a1.htm. Accessed November 20, 2006. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Using Fluoride to Prevent and Control Tooth Decay in the United States Fact Sheet, updated Jan 2011. www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/fact_sheets/fl_caries.htm Department of Health and Human Services. HHS Recommendation for Fluoride Concentration in Drinking Water for Prevention of Dental Caries. Federal Register. Vol. 76(9): January 13, 2011. Krol DM. Dental caries, oral health, and pediatricians. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2003; 33(8):253-270. Lewis CW, Milgrom P. Fluoride. Pediatr Rev. 2003; 24(10):327-336. www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact References, continued 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 47 Lewis DW, Ismail AI. Periodic health examination: 1995 update: 2. Prevention of dental caries. The Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. Can Med Assoc J. 1995; 152(6): 836-46. Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Logan S, Sheiham A. Fluoride varnishes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD002279. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002279. This version first published online: 21 January 2002 in Issue 1, 2002. Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Logan S, Sheiham A. Topical fluoride (toothpastes, mouthrinses, gels, or varnishes) for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD002782. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002782. This version first published online: 20 January 2003 in Issue 1, 2003. Oral health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000. Available online at: http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/DataStatistics/SurgeonGeneral. Accessed November 20, 2006. Rozier RG, Adair S, Graham F, et al. Evidence-Based Clinical Recommendations on the Prescription of Dietary Fluoride Supplements for Caries Prevention. A Report of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. JADA. December 2010 www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact vol. 141(12): 1480-1489. References, continued 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 48 US Environmental Protection Agency. 40 CFR Part 141.62. Maximum contaminant levels for inorganic contaminants. Code of Federal Regulations 2002:428-9. US Environmental Protection Agency. 40 CFR Part 143.3 National secondary drinking water regulations. Code of Federal Regulations 2002; 614. United States Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical preventive services, 2010-2011. Available online at: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/pocketgd.htm. Accessed January 28, 2011. Wright JT, Hanson N, Ristic H, et al. Fluoride toothpaste efficacy and safety in children younger than 6 years. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014; 145(2):182-9. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Prevention of Dental Caries in Children from Birth Through Age 5 Years. May 2014. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsdnch.htm Clark MB, Slayton RL; AAP Section on Oral Health. Fluoride use in caries prevention in the primary care setting. Pediatrics. 2014 Sep;134(3):626-33. www.aap.org/oralhealth/pact