TP #6 The Industrial Revolution Packet

advertisement

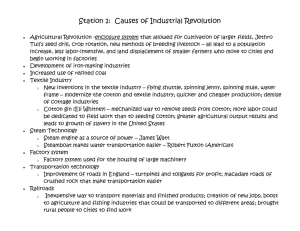

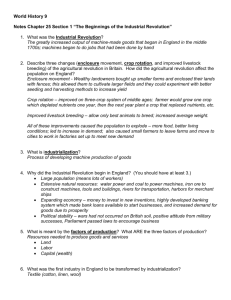

Turning Point #6: The Industrial Revolution c. 1700 – 1800s A.D. NAME: ____________________________________________ DATE DUE: _____________________ PERIOD: ____________________ SCORE: _______/10 Essential Question for TP #6 What were the effects of the Industrial Revolution on the geography, economics, culture, and politics of our world? TP #6 Vocabulary Directions: Please follow the directions given in each section. Much of this homework should be done in the first 5 minutes of each class period as an entry task. If you are not finished with the homework by Thursday night you must have it finished before Friday morning. Grading: SCORE:______/2 Vocabulary: Define each word using the text in this packet. Please write the full text of the definition. Do not shorten, or write a definition from a dictionary. 1. Industrial Revolution - 2. Mechanization – 3. Mass Production - TOP 10 Inventions Score: _______/2 GROUP 1 GROUP 2 FINAL GROUP 1. 1. 1. 2. 2. 2. 3. 3. 3. 4. 4. 4. 5. 5. 5. 6. 6. 6. 7. 7. 7. 8. 8. 8. 9. 9. 9. 10. 10. 10. Mechanization and Industrialization Notes SCORE: ______/2 I. Beginnings A. 1. Jethro Tull’s “Seed Drill” 2. B. 1. 2. Labor – people to work 3. II. Inventions A. 1. 2. *8 times the normal production 3. 4. 1793 – Eli Whitney’s Cotton Gin B. 1. 2. Late 1700s – Coal and Iron ore mined in Britain 3. C. Transportation and Communication 1. 2. 1808 – Robert Fulton invents the steamboat 3. D. Factory Breakthroughs 1. 2. Assembly Line (1913) – 3. Ford’s “Model T” Car A. 1908 B. 1924 - III. Factories A. Work 1. 2. 3. Assembly Line = Mass Production B. 1. 2. Growing opportunities for women 3. 4. IV. Conclusion A. Industry feeds itself and inventions move industry quickly into the future B. C. D. Citation: VanDerPuy, Abraham . "Mechanization and Industrialization." Auburn High School. 23 Apr. 2013. Lecture. The Industrial Revolution: A Great Leap Forward Social Science Perspectives: - Economy - Geography - Culture - Politics Getting new clothes in the 17th century was no simple matter. Most people in rural areas made their own. They had to spin the yarn and weave the fabric before sewing the clothing itself. They also may have made textiles (fabrics) and sewn clothing for a merchant who sold the finished products in the cities. In rural England, for example, textile production was one of the main work-at-home, or "cottage," industries. Many other items were manufactured (changed from raw material to finished product) by people working in their own homes, in England and in other parts of the world. By the 18th century, however, many new inventions sped up the manufacturing process tremendously. These inventions set in motion a period that is now called the industrial revolution. The ways in which people worked, lived, and thought changed dramatically. Many people no longer lived in small villages surrounded by farms. Instead large numbers of rural farmers and craftspeople moved to cities to operate machinery in factories. The factory work used more natural resources than had previously been needed, especially iron and coal. This demand and use increased as the industrial revolution spread from England throughout Europe and to North America. Innovations in Textiles Until the 1700s, fabrics were made on a loom by a person weaving by hand. The weaver sent yarn back and forth across the threaded loom on a shuttle--the weaver's equivalent of a needle. John Kay invented a mechanical shuttle, patented in 1733, which made weaving much faster. This mechanical process, however, used yarn faster than spinners were able to produce it. In the mid-1760s, James Hargreaves solved that problem by inventing another machine. Called the “Spinning Jenny,” it allowed people to spin yarn fast enough to keep up with the weavers' needs. Other improvements followed, until the machines could work a hundred times faster than hand weavers. Having all the work done in a mill allowed a merchant to centralize the whole process of cloth production. Besides being speedier, machines cost less to run per unit of fabric than it cost to pay workers in their homes. People who had worked by hand in their homes in the countryside now came to work the machines at a mill. By 1780, England had 140 mills. The industrial revolution was underway. The Cotton Gin and Textile Production As the supply of textiles increased, the price of cotton cloth went down. As a result, demand increased and so did the need for more raw cotton. Raw cotton imports by England went from 4 million pounds in 1761 to 100 million pounds in 1815. Most of it came from the southern United States. Cleaning seeds from the cotton fiber was slow work done by slaves by hand. In 1793 American Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, a machine that could clean much more cotton in a day than hand laborers could. With Whitney's invention, the southern United States became the cottonproducing center of the world. As production soared, so did the profits made by using slave labor to plant and pick cotton. Thus, the cotton gin had the unintended side effect of helping to expand The Cotton Gin slavery in the United States. Full Steam Ahead Manufacturers first built mills next to large rivers and used the river water to power water wheels to operate the machines. In the 1760s, however, another major invention provided a power source that could be used anywhere: the steam engine. Several earlier inventors had created steam-powered engines. But the improved engine built by James Watt in 1765 (patented 1769) was the first that could run the large machines in textile mills. When water is changed to steam by heating, its volume expands greatly. The force produced by this increasing volume is the moving force in all steam engines. In a basic steam engine, a rod, called a piston, is free to move back and forth in a closed container, called a cylinder. When very hot steam is let into one end of the cylinder, the steam forces the piston to move to the other end. This steam then exits the cylinder through an exhaust valve. Then steam enters the other end of the cylinder and forces the piston back the other way. This steam also exits through an exhaust valve, and the cycle begins again. A rod connected to the moving piston turns a wheel or moves some other machine part. Like other engines, the steam engine needed fuel to burn. England had large deposits of coal to fuel the new steam engines, making it possible for people to use more machines and to build larger factories. Steam engines in trains and ships improved transportation. The first public train, in 1825, carried both passengers and freight between the English cities of Stockton and Darlington. Iron production began to boom as metalworkers tried to keep up with the demand for more steam engines, more locomotives, and more rails, not only in England but elsewhere in western Europe and in the United States. Urbanization Cities changed from centers of trade to production centers. The demand for workers in the growing mills and factories led many people to leave farms and villages to look for work in the cities. Factories hired anyone able to do a simple task; men, women, and children (many under the age of 10) worked up to 14 hours a day, six days a week, often in places with little light or fresh air. There were no safety standards, and accidents in the factories were common, injuring, crippling, and even killing workers. In later years the amount of people being injured or killed each year (especially children) leads many in Europe and America to campaign for worker’s rights. Although unions (worker organizations) were illegal for most of the time during industrialism, many in government attempted to pass laws limiting the amount of time that could be spent in a factory, limiting the amount of child labor, and even passing wage laws. However, the lure of jobs and wealth kept workers in fresh supply for factories. Despite conditions in the factories, people continued to move to the cities to work in factory jobs. For many, the move improved their standard of living. In many places farm workers worked even longer hours than factory workers, and bad weather might wipe out their crops. In villages many people earned their living by manufacturing textiles by hand in their own homes. A small cottage that doubled as a home and a manufacturing workshop was noisy, dirty, and uncomfortable. Many of these people were relieved to have the manufacturing operation moved out of their homes and into a central factory. By 1850, half of England's people lived in cities. Sanitary facilities could not keep pace with the rapid growth. That created health and environmental problems. Sewage flowed down the streets and emptied into streams and rivers. Wastes from the factories also emptied into streams. Smoke and soot from coal-burning engines billowed from factory chimneys. The constant noise of machines filled the air. The industrial revolution changed the world in major ways. It introduced machines to do much of the work previously done by humans and replaced human and animal power with engines. For most people, the economic situation improved. With the positive effects, however, came the negative impacts of air, water, and noise pollution that affect us to this day. Citation: "Industrial Revolution." Earth Explorer. 1995. eLibrary. Web. 29 Mar. 2012. Social Science Categories and The Industrial Revolution: A Great Leap Forward Score: _______/2 1. Provide one detailed example from the article that shows that the Industrial Revolution affected the economy of the time. 2. Provide one detailed example from the article that shows that the Industrial Revolution affected the geography of the time. 3. Provide one detailed example from the article that shows that the Industrial Revolution affected the culture of the time. 4. Provide one detailed example from the article that shows that the Industrial Revolution affected the politics of the time. The Changing Face of Work Social Science Categories: - Economy - Culture - Politics Because steam engines and machines were expensive to buy and maintain, businessmen were anxious to run them as efficiently as possible. They built factories to house their machinery, and workers had to travel there to work, instead of working in their own homes, or in small forges and workshops. Workers had to work at the pace set by the machines, instead of their own pace. Many workers resisted the coming of the machines. For example, hand weavers feared that the power looms would eliminate the need for their craft skill and destroy their way of life. They had reason to be afraid: while there were about 250,000 home weavers in Britain 1820, the number fell to under 50,000 by 1850. When the first textile machines were installed, gangs of masked workers broke into factories at night to smash them. They were known as Luddites, a name derived from that of a weaver named Ned Ludd, who inspired their movement. Between 1811 and 1816 the Luddites caused widespread damage. As the violence spread, the rioters ended up killing one manufacturer. The alarmed government sent thousands of troops to deal with the Luddites, and 23 protesters were hanged and many more were imprisoned. Workers' protests of this kind were by no means confined to Britain but occurred wherever factory owners introduced machines that threatened home production. For example, textile workers in Germany destroyed machines in the 1820s. In France, protestors destroyed some 81 sewing machines installed in a workshop in 1841. In addition, agricultural workers smashed threshing machines, which they thought would take away their jobs,in a series of riots that swept across southeast England in the 1830s. At first, most factories were small, employing fewer than 100 workers. These early factories allowed families to remain together; for instance, in cotton textile factories the husbands wove the cloth, the wives spun the thread, and the children carried materials to their parents. Ultimately, though, factories disrupted family life. Women and children In a British cotton mill around 1812, two Luddites set about could easily operate the new steam-driven machines. wrecking the machinery they fear will put them out of work. The They were paid lower wages than men, so the textile term "Luddite" has come to mean a person who is hostile to technological change. (Tom Morgan/Mary Evans Picture Library) factories ceased to employ men. Of course, factories did not replace all the older ways of manufacturing goods overnight. Generally speaking, businessmen established factories only in situations where either the cost of the machinery or the complexity of the manufacturing process warranted the creation of large-scale operations. Even by the middle of the 19th century, only about 11 percent of British workers worked in factories. Many industrial workshops were very small, employing only one or two people, but they were often located close to the larger factories and supplied them with semi-finished goods for processing. So manufacturing came to be concentrated in small areas, close to sources of coal and iron ore or centers of transportation. As the 19th century progressed, more and more manufacturing was performed in factories. Working in a factory was both hazardous and difficult. Because labor was cheap and machines were expensive, factory owners were more interested in ensuring that their machines ran efficiently than in the safety of their workforce. Workers had to put in long, punishing hours at the machines carrying out boring, repetitive, and often dangerous work. A worker unable to work because of injury was simply fired. In factories and mines, small children were employed to squeeze into narrow places to clean machinery or haul out the coal through low passages. During the 19th century, working people came together to find ways to protect their interests and improve their working conditions. One way to do this was to withhold their labor by going on strike. Labor unions sprang up in Britain and across Europe to fight for workers' rights. Eventually political parties developed to represent and champion the views of working people. Governments feared that these organizations would spread revolutionary ideas, and often tried to suppress them. Many countries introduced limited social reforms (such as ending the employment of children) for humane reasons and to meet the workers' demands. Citation: Carlson, W. Bernard, Ed.. 15: The Changing Face of Work. Oxford University Press, 2005. eLibrary. 07 Nov. 2012. Social Science Categories and The Changing Face of Work Score: _______/2 1. Provide one detailed example from the article that shows that the Industrial Revolution affected the economy of the time. 2. Provide one detailed example from the article that shows that the Industrial Revolution affected the culture of the time. 3. Provide one detailed example from the article that shows that the Industrial Revolution affected the politics of the time.