Chapter 15

advertisement

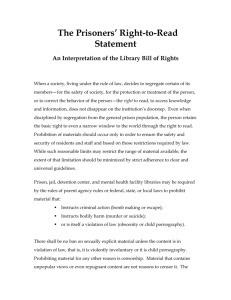

Part II Constitutional Law of Corrections Chapter 15 – Eighth Amendment: Conditions of Confinement – Cruel and Unusual Punishment Introduction: This chapter examines the phrase “cruel and unusual punishment” with respect to the conditions under which inmates are held Chapter Outline Conditions in Prison Opening the Gates Crowding in Prisons and Jails Effect of the Prison Litigation Reform Act Bell v. Wolfish Rhodes v. Chapman Chapter Outline: cont’d Whitley v. Albers Wilson v. Seiter Hudson v. McMillian Farmer v. Brennan Helling v. McKinney Qualified Immunity Conditions in Prison Historically, the courts had a “handsoff” attitude towards prisons Gave no constitutional guidelines for the management of prisons Constitution was not seen as providing the courts the keys to unlock the doors and to look into prison conditions This view changed beginning in the 1960s Opening the Gates Wright v. McMann (1967) – Inmate in Clinton State Prison in New York filed suit, without assistance of counsel, under Section 1983, claiming prison conditions in solitary confinement were deplorable Said he was in this cell for 33 days, beginning in February 1965, and another 21 days in 1966 Opening the Gates: cont’d A few of the claims Cell was dirty, with no means to clean Toilet and sink encrusted with slime and human excrement Left nude for several days, and later given only a pair of underwear Opening the Gates: cont’d No hygiene items Windows in his cell were left open, causing exposure to the cold winter air during subfreezing temperatures Had to sleep on the cold concrete floor without bedding Opening the Gates: cont’d Appeals court in Wright gave brief overview of the history of the Eighth Amendment, referencing the Supreme Court’s holding in Weems (1910) “[The Constitution]. . . may acquire meaning as public opinion becomes enlightened by a humane justice” The concept of “cruel and unusual punishment” is found in an ever-changing state of public opinion – the views of American society Opening the Gates: cont’d In Wright, the appeals court said the alleged conditions if established would be cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment “The Eighth Amendment forbids treatment so foul, so inhuman, and so violative of basic concepts of decency” Opening the Gates: cont’d The appeals court in Wright returned the case to the trial court for a hearing on the truthfulness of the charges If proved, Wright would be entitled to relief under Section 1983 A judge concurring in this holding, warned that this would open the courts to a flood of complaints under Section 1983 Crowding in Prisons and Jails Many prisons are crowded beyond their desirable capacity Such crowding can lead to other problems - budgetary, program dilution, tensions within prison Crowding in Prisons and Jails: cont’d Term “overcrowding” seen as inappropriate – as making a judgment on what level of prison population is bad Prisons and jails can be effectively run at a population above capacity – adequate funding and resources are two factors that contribute to this Better way to describe, absent a population that has reached a truly unmanageable level, is “crowding” Crowding in Prisons and Jails: cont’d Crowding in prisons has led to many lawsuits, most under § 1983 Many suits have led to court orders or consent decrees requiring corrective actions At least 40 states have been under such orders or decrees Crowding in Prisons and Jails: cont’d Consent decrees are agreements by the parties and approved by the court that certain actions will occur to improve conditions Some defendant–administrators have signed such agreements because they agreed with the provisions and wanted to see the changes Crowding in Prisons and Jails: cont’d Consent decrees also have significant drawbacks: The duration of the consent decree – can be an albatross passed from one administrator to the next The requirement for adherence to the agreement regardless of subsequent occurrences – failure to adhere could place prison officials in contempt Crowding in Prisons and Jails: cont’d Interesting question – what right does an administrator have to sign an agreement that requires the government to spend large sums of taxpayer money for programs or changes he feels are desirable What right exists to bind future legislators or governors to that course of expensive changes Short answer – no such right or authority - the power to raise money for the government and to decide where it is spent is with the legislative branch Crowding in Prisons and Jails: cont’d Some court decisions involving conditions of prisons or jails led to court-appointed masters to assist the court in the administration of the granted relief Crowding in Prisons and Jails: cont’d The appointed masters were to be assistants to the judges However, provided wide authority by appointing judges, masters, at times, became involved in day-to-day prison management or were authorized to look over the shoulders of administrators in many different aspects of their job Crowding in Prisons and Jails: cont’d The Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) provides prison officials with some relief regarding consent decrees and masters Effect of the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) While does not change inmate’s substantive rights, does establish guidelines (such as requiring “exhaustion”) The PLRA reflects congressional intent to limit judicial management of prisons Effect of the PLRA: cont’d Consent decrees – PLRA defines as relief entered by the court that is based in whole or in part upon the consent or acquiescence of the parties; does not include private settlements Relief – refers to all relief that may be granted or approved by the federal court and includes consent decrees Effect of the PLRA: cont’d Prospective relief in a civil action with respect to prison conditions may be granted or approved by the federal court only upon: Finding that the relief is narrowly drawn Extends no further than necessary to correct the violation of a federal right, and Effect of the PLRA: cont’d Is the least intrusive means necessary to correct that violation The court must also give substantial weight to any adverse impact the proposed relief has on public safety or the operation of the criminal justice system Effect of the PLRA: cont’d On existing consent decrees, the PLRA provides: For termination of a decree, upon motion of any party or intervener, no later than two years after the date the court granted or approved the prospective relief One year after the court has entered an order denying termination of prospective relief; or For orders issued prior to the PLRA’s enactment date, two years from the date of the PLRA’s enactment Effect of the PLRA: cont’d A different section of the PLRA places limitations on special masters, including a ban on them making findings or ex parte communications Effect of the PLRA: cont’d Miller v. French (2000) – dates back to 1975 and an inmate class action suit on conditions of confinement Constitutional violations found and lower courts ordered injunctive relief, remaining in effect through current litigation Last modification occurred in 1988 Effect of the PLRA: cont’d In 1997, the state, citing the PLRA, filed a motion to end the prospective relief Inmates opposed action – saying the PLRA’s automatic stay provision (temporary suspension of the court-ordered injunctive relief) violated the separation of powers doctrine Supreme Court held for government – saying that the stay “merely reflects the changed legal circumstances” Effect of the PLRA: cont’d Court held prospective relief under the existing decree is no longer enforceable, and that it remains unenforceable unless and until the court makes the required findings that prospective relief continues to be necessary to correct a current and ongoing violation of the federal right it extends no further than necessary to correct the violation of the federal right and that the prospective relief is narrowly drawn, and the least intrusive means to correct the violation Effect of the PLRA: cont’d Gilmore v. People of the State of California (2000) – state officials, pursuant to the PLRA, filed for termination of court orders dating back to 1972 and consent decrees dating back to 1980 Appeals court noted that no circuit court has found the PLRA to violate due process or the Equal Protection clause; the court said it declined “to stray from these precedents” Effect of the PLRA: cont’d Inmates of Suffolk County Jail v. Rouse (1997) – dated back to 1971, primarily involving double-bunking of pretrial detainees 1979 consent decree ratified plan for new facility with single occupancy cells, and phasing out old jail For various reasons, wasn’t until mid-1990s when new facility was done Difficulty encountered in adhering to single occupancy Effect of the PLRA: cont’d Consent decree modifications in 1985, 1990 and 1994 Following passage of PLRA, state filed suit to terminate the decree Appeals court ordered termination of the consent decree Found the PLRA legislation to be rational Withdrawal of prospective relief does not diminish the right of access PLRA does not impair a fundamental right Effect of the PLRA: cont’d Imprisoned Citizens v. Ridge (1999) – appeals court held that while the PLRA’s provision for immediate termination of prospective relief singles out certain prisoner rights cases for special treatment, it does so only to advance unquestionably legitimate purposes “to minimize prison micro-management by federal courts and to conserve judicial resources” Effect of the PLRA: cont’d Benjamin v. Fraser (2001) – suit first brought in 1975, alleging conditions in New York City jails violated pretrial detainees’ constitutional rights Original consent decrees dated to 1978-79 State, under PLRA, attempted to terminate operation of the decrees Effect of the PLRA: cont’d Lower courts refused to terminate decree provisions involving attorney visitation Family were allowed to visit during “count”; attorneys were not – no justification for distinction was provided No rationale provided as to why the process of bringing detainees to the counsel rooms could not begin upon the attorney’s arrival at the prison, rather than his arrival at the visiting area The district court had found that attorneys were forced to wait 45 minutes to two hours or longer, after arriving Effect of the PLRA: cont’d No reasons provided why a space reservation policy could not be used in those institutions with limited visiting areas Appeals court found measures ordered by earlier consent decrees to be reasonable To safeguard the detainees’ constitutional rights at minimal cost to the department and The safeguards did not impair institutional concerns Effect of the PLRA: cont’d Appeals court affirmed the “continuing need for prospective relief to correct an ongoing denial of a federal right, and that the relief ordered was sufficiently narrow to satisfy the requirements of the PLRA” Bell v. Wolfish (1979) First Supreme Court case dealing with conditions of confinement, and interpreting the Eighth Amendment Discussed previously with respect to the publishers-only rule for incoming publications and the inspection of personal packages in Chapter 7 (First Amendment), and the issue of searches in Chapter 10 (Fourth Amendment) Bell v. Wolfish: cont’d Eighth Amendment also a focus in the case Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC) New York had a planned capacity of 449 inmates Primarily single occupancy rooms Increased confinement numbers led to doublebunking Issue - is it a constitutional violation to “overcrowd” – that is to place two or more inmates in a space planned or designed for one Bell v. Wolfish: cont’d Because the inmates were pretrial detainees, inmates could not be punished at all; issue was one of due process Under the due process clause, a detainee may not be punished prior to an adjudication of guilt in accordance with due process of law Court focus was to look at whether the conditions or restrictions of pretrial detention amounted to punishment of the detainees Bell v. Wolfish: cont’d Court held that if a particular condition or restriction of pretrial detention is reasonably related to a legitimate governmental objective, it does not, without more, amount to “punishment” But, if a restriction or condition is arbitrary or purposeless – a court could permissibly infer that the purpose of the governmental action was punishment Bell v. Wolfish: cont’d Court held in Wolfish that as a matter of law, the double-bunking as done at the MCC did not amount to punishment and thus did not violate inmates’ rights under the due process clause Court held the government must be able to take steps to maintain institution security and order Bell v. Wolfish: cont’d The Wolfish ruling is important on two points It provided the standard for measuring the constitutionality of conditions for pretrial detainees, and It ruled that double-bunking is not per se unconstitutional Bell v. Wolfish: cont’d The Wolfish decision has allowed jails to be double-bunked and otherwise crowded, so long as the conditions do not become “genuine privations and hardships over an extended period of time” Rhodes v. Chapman (1981) In Rhodes v. Chapman, the issue was whether the housing of two inmates in a single cell at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility is cruel and unusual punishment, prohibited by the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments Inmates brought the Section 1983 action, claiming that double-celling resulted in inmates living too closely together, and that the crowding strained the prison’s facilities and staff Rhodes v. Chapman: cont’d This maximum security prison opened in the early 1970s It had 1,620 cells, each 63 square feet At the time of the lawsuit, the prison had 2,300 inmates, most doing long-term sentences Most inmates had to spend 25% of their time in their cells Rhodes v. Chapman: cont’d Court noted that conditions could not involve the wanton and unnecessary infliction of pain, nor be grossly disproportionate to the severity of the crime warranting confinement This is the current “standard of decency” to measure whether conditions amount to cruel and unusual punishment Rhodes v. Chapman: cont’d Court, using this standard, found no cruel and unusual punishment in double bunking per se, or on the conditions that prevailed at the prison, saying “(T)he Constitution does not mandate comfortable prisons” Whitley v. Albers (1986) Whitley v. Albers focused on the use of force Inmates at the Oregon State Penitentiary took control of a two-tiered cellblock Inmate Albers lived in the cellblock An officer was taken hostage, and was being held on the upper tier Whitley v. Albers: cont’d Officers formed an assault squad to regain control of the cellblock Captain Whitley was going to go to the second tier in an effort to free the hostage Three officers were told to shoot low at any inmates trying to climb the stairs to the second tier – because they would be a threat to Captain Whitley or the hostage Inmate Albers started up the stairs after Whitley had run up; Albers was shot in the left knee Hostage was rescued and cellblock retaken Whitley v. Albers: cont’d Inmate Albers filed a § 1983 action alleging Eighth Amendment deprivations because of the physical damage to his knee, plus mental and emotional distress Whitley v. Albers: cont’d Court ruled for government, holding that whether the measure taken inflicted unnecessary and wanton pain and suffering ultimately turns on “whether force was applied in a good faith effort to maintain or restore discipline or maliciously and sadistically for the very purpose of causing harm” Whitley v. Albers: cont’d Court held that the situation at the penitentiary was “dangerous and volatile” Saw the shooting as within the good faith effort to restore prison security Court held no Eighth Amendment violation occurred Tennessee v. Garner (1985) Case involved the shooting of a fleeing suspect by a police officer Court set three standards to be met for the use of force Tennessee v. Garner: cont’d 1. Force must be necessary to prevent the escape of the subject 2. Must be probable cause for the officer to believe that the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious bodily injury to the officer or others, and 3. If possible there must be some kind of warning given to the fleeing person before deadly force is used Tennessee v. Garner: cont’d Analysis is seen as applicable in looking at the use of force in a prison or jail First element seen as implicit in using force to stop an escapee or would-be escapee In a prison disturbance or in an escape, elements 2 and 3 should also be followed Tennessee v. Garner: cont’d In a prison that houses convicted felons or those accused of violent crimes, 2nd element appears to be met – to require staff in a prison or jail to identify a person scaling a wall or fleeing from the prison, before shots can be fired, ordinarily would not be reasonable Tennessee v. Garner: cont’d Every facility should establish a policy on use of force and especially define those limited situations where deadly force may be used All staff should be fully trained on the policy guidelines Wilson v. Seiter (1991) Case involved the conditions of confinement Inmate in Ohio facility claimed under Section 1983 that his Eighth Amendment rights were infringed by his treatment Overcrowding Excessive noise Insufficient locker storage space Inadequate heating and cooling Wilson v. Seiter: cont’d Improper ventilation Unclean and inadequate restrooms Unsanitary dining facilities and food preparation, and Housing with mentally and physically ill inmates Wilson v. Seiter: cont’d Supreme Court qualified its guidance in Whitley as applying to those circumstances in which officials were reacting to an emergency situation Did not see this high standard – wanton misconduct shown by actions done “maliciously and sadistically for the very purpose of causing harm” - applying to prison conditions cases Wilson v. Seiter: cont’d Held that in general poor-condition cases, such as Wilson, the state of mind of prison officials was determinative To sustain a finding of cruel and unusual punishment, need to show a “deliberate indifference” on the part of officials to the basic needs of the inmate Each need of inmates, or each claimed violation of constitutional standards, would have to be examined separately to determine the existence of deliberate indifference Wilson v. Seiter: cont’d Not proper to look at “overall conditions” to decide cruel and unusual punishment “Nothing so amorphous as “overall conditions” can rise to the level of cruel and unusual punishment when no specific deprivation of a single human need exists” Case remanded to the lower courts to determine whether any one condition violated the “deliberate indifference” standard Hudson v. McMillian (1992) Case looked at what degree of injury is required before an inmate can claim an Eighth Amendment—cruel and unusual punishment—violation Hudson, a Louisiana inmate, claimed he was beaten by guards while he was handcuffed and shackled Said he sustained minor bruises, some facial swelling, loosened teeth, and a cracked dental plate Hudson v. McMillian: cont’d Appeals court held there must be a “significant injury” to constitute an injury recoverable under the Eighth Amendment Supreme Court reversed, holding the core judicial inquiry is that set forth in Whitley was force applied in a good-faith effort to maintain or restore discipline, or maliciously and sadistically to cause harm Hudson v. McMillian: cont’d Court held that a serious injury was not necessary for an inmate to pursue a cruel and unusual punishment claim Court must look at the particular circumstances Unjustified striking of an inmate would raise a serious question about the concepts of decency that lie behind the Eighth Amendment Hudson v. McMillian: cont’d In Smith v. Mensinger (2002), an appeals court looked at whether a prison officer could be held liable if he had a reasonable opportunity to intervene but refused to do so Smith received misconduct reports, including one for punching an officer in the eye Smith claims he was handcuffed behind his back Hudson v. McMillian: cont’d Claimed several officers then rammed his head into wall and cabinets, and knocked him to the floor, where he was kicked and punched by one officer Inmate said officer Paulukonis saw the beating but made no effort to intervene or restore order Hudson v. McMillian: cont’d Smith filed a § 1983 suit, alleging violation of his constitutional rights, naming several officers as defendants, including officer Paulukonis Federal appeals court said officer Paulukonis could be held liable, provided he had a reasonable opportunity to intervene, and simply did not “The approving silence emanating from the officer who stands by and watches . . . contributes to the actual use of excessive force. . . . Such silence is an endorsement of the constitutional violation resulting from the illegal use of force” Hudson v. McMillian: cont’d Appeals court acknowledged that there could be a greater degree of dereliction of duty for a supervisor than for an officer of lower rank Farmer v. Brennan (1994) Farmer was a biological male who was medically diagnosed as a transsexual He was housed at a federal penitentiary, where he wore clothes in a feminine manner Farmer v. Brennan: cont’d Inmate usually segregated from the general prison population due to his own misconduct and for his safety He was released into the regular population, without any objection by him Within two weeks he was beaten and raped by another inmate Farmer v. Brennan: cont’d Farmer filed a Bivens suit (federal equivalent of a § 1983) Claimed he had been subject to cruel and unusual punishment When transferred to the prison where officials knew there were assaultive inmates And where officials knew he would be particularly vulnerable to sexual attack Farmer v. Brennan: cont’d He claimed this was deliberate indifference to his personal safety on the part of prison officials Lower courts granted prison officials summary judgment Held liability could be found only if officials had actual knowledge of a potential danger to Farmer Such knowledge had not been shown Farmer v. Brennan: cont’d Supreme Court, in remanding the case, stated that prison officials have a duty to protect inmates from violence at the hands of other inmates Farmer v. Brennan: cont’d Court held that a prison official may be held liable under the Eighth Amendment for denying humane conditions of confinement only if he Knows that inmates face a substantial risk of serious harm and Disregards that risk by failing to take reasonable measures to abate it (is deliberately indifferent to inmate health or safety) Farmer v. Brennan: cont’d Court said the fact that the inmate had not given notice that he feared harm was not sufficient to dispose of the case Court said lower court would have to examine the evidence to see if officials had other reasons to know that the inmate faced a “substantial risk” of serious harm and failed to take reasonable steps to avoid that risk Helling v. McKinney (1993) Nevada inmate McKinney filed a § 1983 suit claiming his involuntary exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) posed an unreasonable risk to his health, in violation of the Eighth Amendment Inmate claimed, in part That he suffered from health problems caused by ETS exposure His prison cell mate was a heavy smoker Helling v. McKinney: cont’d Court restated its ruling in other cases that prison officials may not be deliberately indifferent to an inmate’s health problems Question whether standard applied only to current health problems or also to risk of future problems In answering, Court held it would be “odd” to deny an injunction to inmates who plainly proved unsafe, life-threatening conditions on the ground that nothing had yet happened to them Helling v. McKinney: cont’d McKinney also argued prison officials were deliberately indifferent to his concerns That current standards of decency do not support such involuntary exposure as he was required to face in the prison Helling v. McKinney: cont’d Court remanded the case back to the lower court to inquire into the inmate’s allegations To see whether the inmate could show an Eighth Amendment violation based on ETS exposure Court held the following needed to be proved: Helling v. McKinney: cont’d That the inmate was being exposed to unreasonably high levels of ETS That the prison’s intervening adoption of a smoking policy, including the establishment of nonsmoking areas, did not sufficiently reduce the risks to the inmate That the complained of risks violated the contemporary “standards of decency” and That prison officials by their attitude and conduct had shown deliberate indifference to substantial risks to McKinney’s future health Helling v. McKinney: cont’d In Atkinson v. Taylor (2002), an appeals court looked at the standards of decency and deliberate indifference Atkinson was a blind, diabetic inmate, who shared a cell with constant smokers He complained he was exposed, with deliberate indifference, to constant smoking in his cell for over seven months Helling v. McKinney: cont’d He claimed this led to nausea, difficulty breathing, and other symptoms His requests to prison officials to change these conditions were not successful Atkinson filed a § 1983 suit, claiming prison officials violated his Eighth Amendment rights by exposing him to ETS Helling v. McKinney: cont’d The appeals court, in addressing the “contemporary standards of decency” issue cited Helling and its holding that an inmate had a right to be free from levels of ETS that pose an unreasonable risk of future harm The court noted that Atkinson had provided evidence that society has become unwilling to tolerate the continuous unwanted risks of second-hand smoke Helling v. McKinney: cont’d As to deliberate indifference, Atkinson produced evidence that after telling prison officials about his sensitivity to ETS, no change was made The court observed that an inmate cannot simply walk out of his cell whenever he wishes Confining a nonsmoker to a cell with a “constant” smoker for an extended period of time, can transform a “passing annoyance” into a serious ongoing medical need Appeals court held evidence showed deliberate indifference on the part of prison officials Helling v. McKinney: cont’d In Reilly v. Grayson (2002), an asthmatic inmate charged Michigan state prison officials with violation of his Eighth Amendment right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment Inmate said he repeatedly complained to prison officials that his medical problems were worsened by failure to house him in an area free of ETS Claimed this exposed him to an unreasonable risk of harm to his health and Constituted deliberate indifference on the part of prison officials Helling v. McKinney: cont’d Appeals court held for the inmate The court stressed the state’s failure to respond to the repeated medical staff recommendations that the inmate be moved to a smoke-free environment That the record showed the inmate suffered both an increase in the severity of his asthma and the risk of future damage to his health due to his exposure to ETS Helling v. McKinney: cont’d Punitive damages were seen as appropriate based on the defendant’s “reckless . . . disregard of Reilly’s rights” The appeals court further noted that the compensatory and punitive damages and attorney fees were to be paid by the warden and two deputy wardens Liable in personal capacities for harm caused, and for constitutional violation of Reilly’s rights Qualified Immunity Focus – immunity in § 1983 cases, where officials may be personally sued because of claimed violations of the constitutional rights of others Qualified Immunity: cont’d Absolute immunity – persons cannot be sued because actions are protected - in the interest of public policy – provided the actions are part of their official duties Prosecutors, judges, legislators, and jury members have this immunity available Government officials in the executive branch, including prison staff, do not (except for the president) Qualified Immunity: cont’d In Cleavinger v. Saxner (1985), lawyers for prison staff tried to claim absolute immunity Involved a suit against prison disciplinary committee members, who had “tried” a case involving an inmate’s misconduct After finding the inmate committed the prohibited act, the committee imposed a sanction Government argued committee members were acting like judges, and persons who acted like judges in their government roles should be protected Qualified Immunity: cont’d Court rejected the argument Prisons officials were not sufficiently independent Were not professional hearing officers, and Did not have the procedural requirements that a judicial officer would have Qualified, rather than absolute immunity, is available to prison officials Qualified Immunity: cont’d Qualified immunity is available – how it works: Inmates need to show a violation of a constitutional right If this can be shown, it must further be shown that the right was clearly established at the time of the action complained about Qualified Immunity: cont’d If officials can show either of the above conditions is not met, then they (officials) are entitled to qualified immunity If the court is convinced by the prison officials’ arguments, the judge will dismiss the lawsuit Qualified Immunity: cont’d Hope v. Pelzer (2002) – Hope, an Alabama inmate, had been handcuffed to a hitching post in the prison, due to his disruptive conduct He was cuffed with his hands above the height of his shoulders First time he was cuffed, he was offered drinking water and given a bathroom break every 15 minutes Qualified Immunity: cont’d On a second occasion, he was involved in an altercation with an officer at his chain gang’s worksite He was sent back inside the prison, ordered to take off his shirt, and spent the next seven hours attached to the post He received one or two water breaks He received no bathroom breaks Qualified Immunity: cont’d Hope filed a § 1983 action against prison officials, alleging violation of his Eighth Amendment rights Supreme Court held there was an Eighth Amendment violation Found in tying Hope to the hitching post when there was no emergency situation requiring that action This resulted in serious discomfort, including deprivation of bathroom breaks Qualified Immunity: cont’d Court saw such conduct as a violation of the basic concept underlying the Eighth Amendment – nothing less than the dignity of man This met part one of the test for qualified immunity – there was a violation of a constitutional right Qualified Immunity: cont’d On the second part of the test – was the right clearly established – the Supreme Court held it was Court cited earlier lower court cases addressing such actions Also, the U.S. Department of Justice had advised the state to discontinue the use of the post in order to meet constitutional standards Qualified Immunity: cont’d In sum, the Court found prison officials violated clearly established law “Hope was treated in a way antithetical to human dignity” “This wanton treatment was not done of necessity, but as a punishment for prior conduct” Qualified Immunity: cont’d “Even if there might once have been a question regarding the constitutionality of this practice,” the court rulings, plus the Department of Justice report “put a reasonable officer on notice that the use of the hitching post under the circumstances alleged by Hope was unlawful” Qualified Immunity: cont’d Hope shows the importance of keeping prison policy current with developing law, and that prison staff carefully follow the agency’s policy