BAIS Ricky James - Courts Administration Authority

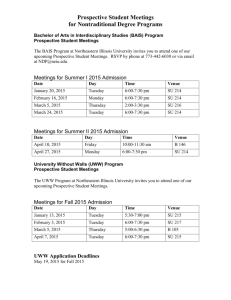

advertisement