Evolution of Computational Approaches in NWChem

advertisement

Evolution of Computational Approaches

in NWChem

Eric J. Bylaska, W. De Jong, K. Kowalski, N.

Govind, M. Valiev, and D. Wang

High Performance Software Development

Molecular Science Computing Facility

Outline

Overview of the capabilities of NWChem

Existing terascalepetascale simulations in

NWChem

Challenges with developing massively

parallel algorithm (that work)

Using embeddable languages (Python) to

develop multifaceted simulations

Summary

Overview of NWChem: Background

NWChem is part of the Molecular Science Software

Suite

Developed as part of the construction of EMSL

Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a DOE BER

user facility, located at PNNL

Designed and developed to be a highly efficient

and portable Massively Parallel computational

chemistry package

Provides computational chemistry solutions that are

scalable with respect to chemical system size as well

as MPP hardware size

Overview of NWChem: Background

More than 2,000,000 lines of code (mostly FORTRAN)

About half of it computer generated (Tensor Contraction Engine)

A new version is released on a yearly basis:

Addition of new modules and bug fixes

Ported the software to new hardware

Increased performances (serial & parallel)

Freely available after signing a user agreement

World-wide distribution (downloaded by 1900+ groups)

70% is academia, rest government labs and industry

Overview of NWChem: Available on many

compute platforms

Originally designed for parallel architectures

Scalability to 1000’s of processors (part even 10,000’s)

NWChem performs well on small compute

clusters

Portable – runs on a wide range of computers

Supercomputer to Mac or PC with Windows

Including Cray XT4, IBM BlueGene

Various operating systems, interconnects, CPUs

Emphasis on modularity and portability

Overview of NWChem: capabilities

NWChem brings a full suite of methodologies to solve

large scientific problems

High accuracy methods (MP2/CC/CI)

Gaussian based density functional theory

Plane wave based density functional theory

Molecular dynamics (including QMD)

Will not list those things standard in most

computational chemistry codes

Brochure with detailed listing available

http://www.emsl.pnl.gov/docs/nwchem/nwchem.html

Overview of NWChem: high accuracy

methods

Coupled Cluster

Closed shell coupled cluster [CCSD

and CCSD(T)]

Tensor contraction engine (TCE)

Spin-orbital formalism with RHF,

ROHF, UHF reference

CCD, CCSDTQ, CCSD(T)/[T]/t/…,

LCCD, LCCSD

CR-CCSD(T), LR-CCSD(T)

Multireference CC (available

soon)EOM-CCSDTQ for excited

states

MBPT(2-4), CISDTQ, QCISD

8-water cluster on EMSL computer:

1376 bf, 32 elec, 1840 processors

achieves 63% of 11 TFlops

CF3CHFO CCSD(T) with TCE:

606 bf, 57 electrons, open-shell

Overview of NWChem: Latest capabilities of

high accuracy

Gas phase

CR-EOMCCSD(T)

DNA

environment

n *

4.76

n *

*

5.24

*

5.01

5.79

TDDFT infty 5.81 eV

EOMCCSD infty 6.38 eV

Surface Exciton Energy: 6.35 +/- 0.10 eV (expt)

Dipole polarizabilities (in Å3)

C60 molecule in ZM3POL basis set:

1080 basis set functions; 24 correlated

Electrons; 1.5 billion of T2 amplitudes;

240 correlated electrons

Wavelength

CC2

CCSD

Expt.

92.33

82.20

76.5±8

1064

94.77

83.62

79±4

532

88.62

NWChem capabilities: DFT

Density functional theory

Wide range of local and non-local

exchange-correlation functionals

Truhlar’s M05, M06 (Yan Zhao)

Hartree-Fock exchange

Meta-GGA functionals

Self interaction correction (SIC) and

OEP

Spin-orbit DFT

ECP, ZORA, DK

Constrained DFT

Implemented by Qin Wu and Van

Voorhis

DFT performance: Si75O148H66,

3554 bf, 2300 elec, Coulomb fitting

Overview of NWChem: TDDFT

Density functional theory

TDDFT for excited states

Expt: 696 nm ; TDDFT: 730 nm

Expt: 539 nm ; TDDFT: 572 nm

Modeling the λmax (absorption maximum) optical chromophores with dicyanovinyl and

3-phenylioxazolone groups with TDDF, B3LYP, COSMO (8.93 → CH2Cl2), 6-31G**,

Andzelm (ARL), et al (in preparation 2008)

Development & validation of new Coulomb attenuated (LC) functionals

(Andzelm, Baer, Govind, in preparation 2008)

Overview of NWChem: plane wave DFT

Plane wave density functional theory

Gamma point pseudopotential and projector

augmented wave

Band structure (w/ spin orbit)

Extensive dynamics

functionality with Car-Parrinello

CPMD/MM molecular dynamics, e.g. SPC/E,

CLAYFF, solid state MD

Various exchange-correlation

functionals

LDA, PBE96, PBE0,(B3LYP)

Spin-Orbit splitting in GaAs

Exact exchange

SIC and OEP

Can handle charged systems

A full range of

pseudopotentials and a

pseudopotential generator

A choice of state-of-the-art

minimizers

Silica/Water CPMD

Simulation

CCl42-/water

CPMD/MM Simulation

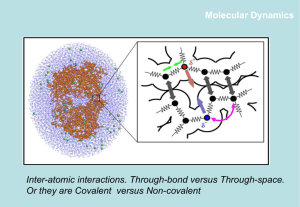

Overview of NWChem: classical molecular

dynamics

Molecular dynamics

Charm and Amber force fields

Various types of simulations:

Energy minimization

Molecular dynamics

simulation including ab initio

dynamics

Free energy calculation

Multiconfiguration

thermodynamic integration

Electron transfer through proton

hopping (Q-HOP), i.e. semi-QM in

classical MD

Implemented by Volkhard group,

University of Saarland, Germany

Set up and analyze runs with Ecce

Overview of NWChem: QM/MM

MM

Seamless integration of molecular

dynamics with coupled cluster and

DFT

QM

QM/MM

Optimization and transition state

search

QM/MM Potential of Mean Force

(PMF)

Modeling properties at finite

temperature

Excited States with EOM-CC

Polarizabilities with linear

response CC

NMR chemical shift with DFT

QM/MM CR-EOM-CCSD Excited

State Calculations of cytosine base

in DNA, Valiev et al., JCP 125

(2006)

Overview of NWChem: Miscellaneous

functionality

Other functionality available in NWChem

Electron transfer

Vibrational SCF and DFT for anharmonicity

COSMO

ONIOM

Relativity through spin-orbit ECP, ZORA, and DK

NMR shielding and indirect spin-spin coupling

Interface with VENUS for chemical reaction dynamics

Interface with POLYRATE, Python

Existing TerascalePetascale capabilities

NWChem has several modules which are scaling to

the terascale and work is ongoing to approach the

petascale

NWPW scalability:

UO22++122H2O

(Ne=500, Ng=96x96x96)

MD scalability: Octanol

(216,000 atoms)

CCSD scalability: C60

1080 basis set functions

Speedup

1000

Cray T3E / 900

750

500

250

0

0

250

500

750 1000

Number of nodes

Existing terascalepetascale Capabilities:

Embarrassingly Parallel Algorithms

Some types of problems can be decomposed and executed in

parallel with virtually no need for tasks to share data. These types

of problems are often called embarrassingly parallel because

they are so straight-forward. Very little inter-task (or no)

communication is required.

Possible to use embeddable languages such as Python to

implement

Examples:

Computing Potential Energy Surfaces

Potential of Mean Force (PMF)

Monte-Carlo

QM/MM Free Energy Perturbation

Dynamics Nucleation Theory

Oniom

….

Challenges: Tackling Amdahl's Law

There is a limit to the performance gain

we can expect from parallelization

Parallel Efficiency

f

Ts

Np

Tp

1

1

f

Np

Np

1 f

f N p 100,

f N p

f N p

f N p

1

f N 1 f

p

Np

1 N p

f N p

My Program

Significant time investment for each

10-fold increase in parallelism!

99%

1000, 99.9%

10000, 99.99%

100, 0.9 99.8877666%

1000, 0.9 99.9888778%

1

2

1

2

1

2

f

1% * 24 hrs 14 min

0.1% * 24 hrs 1.4 min

0.01% * 24 hrs 8.64 sec

0.001122% * 24 hrs 1.62 min

0.000111222% * 24 hrs 9.6 sec

1-f

Challenges: Gustafson’s Law – make the

problem big

Gustafson's Law (also known as Gustafson-Barsis'

law) states that any sufficiently large problem can be

efficiently parallelized

My parallel Program

Tp (a(n) b(n))

Ts (a(n) P * b(n))

Assuming lim n a(n) small and a(n) b(n) 1

b(n)

Then S Ts ( a ( n) P * b( n)) a ( n) P * (1 a ( n))

Tp

(a (n) b(n))

1

P

1 a (n) * (1 )

a(n)

Challenges: Extending Time – Failure of

Gustafson’s Law?

The need for up-scaling in time is especially critical for classical

molecular dynamics simulations and ab-initio molecular dynamics,

where an up-scaling of about a 1000 times will be needed.

Current ab-initio molecular dynamics simulations done over several

months are currently done only over 10 to 100 picoseconds, and

the processes of interest are on the order of nanoseconds.

The step length in ab initio molecular dynamics simulation is on the

order of 0.1…0.2 fs/step

1 ns of simulation time 10,000,000 steps

at 1 second per step 115 days of computing time

At 10 seconds per step 3 years

At 30 seconds per step 9 years

Classical molecular dynamics simulations done over several

months, are only able simulate between 10 to 100 nanoseconds,

but many of the physical processes of interest are on the order of at

least a microsecond.

The step length in molecular dynamics simulation is on the order of 1…2

fs/step

1 us of simulation time 1,000,000,000 steps

at 0.01 second per step 115 days of computing time

At 0.1 seconds per step 3 years

At 1 seconds per step 30 years

Challenges: Need For Communication Tolerant

Algorithms

Speedup for Car-Parrinello Code

T3E

IBM-SP

70.00

speedup

60.00

50.00

40.00

30.00

20.00

10.00

0.00

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Data motion costs increasing due to

“processor memory gap”

Coping strategies

Trade computation for communication

[SC03]

Overlap Computation and

Communication

number of nodes

5

10

Processor

4

10

1200

1100

1000

900

800

700

600

500

400

300

200

100

0

Performance

Time (s)

Scaling of local basis DFT

calculation

(55%/year)

3

10

Memory

[DRAM]

(7%/year)

2

10

1

10

8

16

32

64

Processors

96

128

0

10

1980

1985

1990

1995

Year

2000

2005

Basic Parallel Computing: tasks

Break program into tasks

A task is a coherent piece of work (such as Reading

data from keyboard or some part of a

computation), that is to be done sequentially; it can

not be further divided into other tasks and thus can

not be parallellised.

Basic Parallel Computing: Task

dependency graph

a = a + 2;

b = b + 3

A

2

B

3

C[0]

C[1]

C[2]

for i = 0..3 do

c[i+1] += c[i];

b = b * a;

b = b + c[4]

C[3]

C[4]

Basic Parallel Computing: Task

dependency graph (2)

Critical path

Synchronisation

points

Basic Parallel Computing: Critical path

The critical path determines the time required to

execute a program. No matter how many processors

are used, the time imposed by the critical path

determines an upper limit to performance.

The first step in developing a parallel algorithm is to

parallelize along the critical path

If not enough?

Case Study: Parallel Strategies for Plane-Wave Programs

....... N

e

Ng basis

Ne molecular orbitals

Critical path

Three parallization schemes

parallelization

Distribute basis

Distribute Molecular Orbitals

(i.e. FFT grid)

(one eigenvector per task)

FFT requires communication

<i|j> requires communication

Distribute Brillouin Zone

number of k-points is usually

small

proc=1

proc=2

proc=3

proc=....

• Minimal load

balancing

slab decomposition

Case Study: Speeding up plane-wave DFT

2+

Performance of UO2 +122water

Old parallel distribution

(scheme 3 – critical path)

10000

Norbitals

Ngrid

=N1xN2xN3

Time (Seconds)

Each box

represents

a cpu

1000

100

10

1

1

10

100

Number of CPUs

1000

10000

Case Study: Analyze the algorithm

Collect timings for important components of the

existing algorithm

Rotation Tasks

Overlap Task

Non-Local PSP Tasks

FFT Tasks

1000

10000

1000

1000

100

1000

100

100

10

100

10

10

1

10

1

1

0.1

1

0.1

0.1

0.01

0.01

0.1

1

10

100

1000

10000

1

10

100

1000

10000

0.01

1

10

100

1000

10000

1

10

100

1000

For bottlenecks

Remove all-to-all, log(P) global operations beyond 500 cpus

Overlap computation and communication (e.g. pipelining)

Duplicate the data?

Redistribute the data?

….

10000

Case Study: Try a new strategy

Old parallel distribution

New parallel distribution

Norbitals

Ngrid

=N1xN2xN3

Norbitals

Ngrid

=N1xN2xN3

Case Study: analyze new algorithm

Can trade efficiency in one component for

efficiency in another component if timings are of

different orders

1000

10000

nj=1

nj=2

nj=4

nj=8

nj=16

nj=32

nj=1

nj=2

nj=4

nj=8

nj=16

nj=32

100

10

1000

1000

nj=2

1000

nj=4

100

nj=2

100

nj=4

nj=2

nj=1

nj=4

nj=8

nj=8

nj=16

nj=16

nj=32

nj=32

10

10

1

1

0.1

1

0.1

0.1

0.01

0.1

10

100

1000

10000

0.01

10

100

1000

10000

nj=16

nj=32

10

1

nj=8

100

1

1

nj=1

nj=1

0.01

1

10

100

1000

10000

1

10

100

1000

10000

Case Study: Success!

Python Example: AIMD Simulation

title "propane aimd simulation"

start propane2-db

memory 600 mb

permanent_dir ./perm

scratch_dir ./perm

geometry

C

1.24480654 0.00000000 -0.25583795

C

0.00000000 0.00000000 0.58345271

H

1.27764005 -0.87801632 -0.90315343 mass 2.0

H

2.15111436 0.00000000 0.34795707 mass 2.0

H

1.27764005 0.87801632 -0.90315343 mass 2.0

H

0.00000000 -0.87115849 1.24301935 mass 2.0

H

0.00000000 0.87115849 1.24301935 mass 2.0

C

-1.24480654 0.00000000 -0.25583795

H

-2.15111436 0.00000000 0.34795707 mass 2.0

H

-1.27764005 -0.87801632 -0.90315343 mass 2.0

H

-1.27764005 0.87801632 -0.90315343 mass 2.0

end

basis

* library 3-21G

end

python

from nwmd import *

surface = nwmd_run('geometry','dft',10.0, 5000)

end

task python

Python Example: Header of nwmd.py

## import nwchem specific routines

from nwchem import *

## other libraries you might want to use

from math import *

from numpy import *

from numpy.linalg import *

from numpy.fft import *

import Gnuplot

####### basic rtdb routines to read and write coordinates ###########################

def geom_get_coords(name):

#

# This routine returns a list with the cartesian

# coordinates in atomic units for the geometry

# of given name

#

try:

actualname = rtdb_get(name)

except NWChemError:

actualname = name

coords = rtdb_get('geometry:' + actualname + ':coords')

return coords

def geom_set_coords(name,coords):

#

# This routine, given a list with the cartesian

# coordinates in atomic units set them in

# the geometry of given name.

#

try:

actualname = rtdb_get(name)

except NWChemError:

actualname = name

coords = list(coords)

rtdb_put('geometry:' + actualname + ':coords',coords)

Python Example: basic part of Verlet

loop

#do verlet step-1 verlet steps

for s in range(steps-1):

for i in range(nion3): rion0[i] = rion1[i]

for i in range(nion3): rion1[i] = rion2[i]

t += time_step

### set coordinates and calculate energy – nwchem specific ####

geom_set_coords(geometry_name,rion1)

(v,fion) = task_gradient(theory)

### verlet step ###

for i in range(nion3):

rion2[i] = 2.0*rion1[i] - rion0[i] - dti[i]*fion[i]

### calculate ke ###

vion1 = []

for i in range(nion3):

vion1.append(h*(rion2[i] - rion0[i]))

ke = 0.0

for i in range(nion3):

ke += 0.5*massi[i]*vion1[i]*vion1[i]

e = v + ke

print ' '

print '@@ %5d %9.1f %19.10e %19.10e %14.5e' % (s+2,t,e,v,ke)