Physical activity - Pennington Biomedical Research Center

advertisement

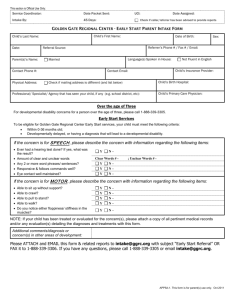

Exercise and Your Health Pennington Biomedical Research Center Division of Education First, we’ll need to define some terms… 1. Homeostasis: This refers to the ability or 2. Energy Expenditure: The act or process of 3. Thermogenesis: Generation or production of tendency of an organism or cell to maintain internal equilibrium by adjusting its physiological processes. Once a weight loss or desired weight is achieved, this is what you want. This is what your body strives for at all times. using up energy. This is one component that must be considered when striving to achieve homeostasis. heat, especially by physiological processes. This is one of three components to energy expenditure. 2009 2 First, we’ll need to define some terms… 4. Basal Metabolism: The minimal amount of 5. Satiety: The condition of being full or 6. Hunger: Refers to a strong desire or “need” energy required to maintain vital functions in an organism at complete rest. This is measured by the basal metabolic rate (BMR) in a fasting individual who is resting in a warm and comfortable environment. gratified beyond the point of satisfaction. Often times, we ignore this feeling or fail to notice it when eating. for food. It is the discomfort, weakness, or pain caused by a prolonged lack of food. It is not the same as appetite, or craving foods. 2009 3 Energy Expenditure Components Made up of three dominant components: Basal metabolism Thermogenesis Physical activity Thermogenesis includes the dietary-induced and thermoregulatory components Only physical activity has a substantial element of voluntary control. 2009 4 Energy Intake Energy intake, on the other hand, is entirely voluntary, except in clinical conditions. Therefore, the modifiable aspects of the energy balance equation amount to just two variables: Physical activity Food intake 2009 5 The Two Sides to Over Eating Under Activity Over Eating Driven by the technological revolution Driven by the agricultural revolution Inactivity, combined with overeating appear to be the largest contributors to the obesity epidemic. When energy intake (energy in) and physical activity (energy burned) are at balance with one another, the body is at homeostasis. There is no weight loss, and there is no weight gain. Weight is simply maintained where it is. This is the ideal situation, provided the individual is at a healthy weight. 2009 6 Set Point Theory Body homeostasis Previous animal experiments indicate that there is a “set point” of body weight that is correctly defended under most conditions. Studies have demonstrated that there are natural feedback systems capable of regulating energy homeostasis with great precision in animals. The same is true for humans. The body wants there to be a balance between energy intake and expenditure. 2009 7 Overview of Energy Balance When energy intake is greater than energy expenditure, there is a net weight gain The Energy Balance Energy intake > Energy expenditure = weight gain When energy intake is less than energy expenditure, there is a net weight loss Energy intake < Energy Expenditure = weight loss Intake Output When energy intake and energy expenditure are at equilibrium with one another, weight is maintained Energy intake = Energy Expenditure = weight maintenance To lose weight, an energy imbalance eliciting an energy deficit is required. This can be done through dieting, exercising, 2009 or a combination of both. Calories From Foods Calories Used During Physical Activity 8 Set Point Theory Body homeostasis However, these feedback loops have been shown to only function appropriately within the settings in which they were originally developed. They have been shown to be easily disrupted by changes in the external environment, such as inactivity and the over consumption of energydense foods. In experimental animals, research shows that their ability to regulate energy balance was impaired once their movement was restricted and they were forced to become physically inactive. In addition, when their low-fat laboratory chow was replaced by a “cafeteria diet” with energy-dense and highly palatable foods, extreme obesity with massive fat deposition was the outcome. 2009 9 Set Point Theory Body homeostasis Similar outcomes have been noted in experiments involving humans where normal lean volunteers were asked to eat a diet prepared for them at the amount that they would normally consume per meal. These individuals were unaware that the fat content (and hence energy density) of the diets differed between each of the three dietary treatments. Energy balances were shown to be strongly influenced by the energy densities of the diets. This was believed to be due to a physiologic failure to recognize that the energy content of the diets differed and so, appetite or energy expenditure was not modified accordingly. 2009 10 Imbalances Physical Activity and Food Intake A survival imperative common to all mammals is: The ability to maintain the body’s energy reserves in the form of hepatic (liver) and muscle glycogen, together with at least a limited supply of fat These energy reserves are necessary to support basic physiologic and immune functions, and to mount fight or flight responses. Because of these essential needs, hunger is believed to have evolved to be a strong physiologic drive made up by robust neuro-endocrine mechanisms, which are protected by multiple levels of redundancy. The same is true for humans. 2009 11 Imbalances Physical Activity and Food Intake Due to recurrent periods of food shortage and famine throughout time, it is believed that evolutionary pressures led to the ability for fat storage to well exceed that which is needed for day-to-day survival in humans. As a result, there has never been the imperative to develop strong satiety mechanisms. This imbalance between effectiveness of hunger and satiety signals is believed to lead to an asymmetry in appetite control. This could possibly explain why current lifestyles create such a high level of susceptibility to obesity in most individuals. 2009 12 Imbalances Physical Activity and Food Intake Because of this imbalance, many individuals have to learn to adopt cognitive dietary restraints in place of their natural physiologic regulatory system in order to maintain leanness. With the previous evidence in mind, this provides further support on the importance of exercise in aiding in body weight regulation. 2009 13 Imbalances Physical Activity and Food Intake Consequences of this asymmetry in appetite control are believed to be further confounded by marketing trends towards larger portion sizes and increased energy density of foods, each of which opposes the need of adapting a lower calorie intake in a progressively more sedentary world. 2009 14 The Importance of Exercise There are a number of published studies indicating that physical activity benefits stable weight maintenance, especially after a weight loss. The real benefit is not particularly during the weight loss itself, although it does contribute to the weight loss when combined with a dietary restriction, but more so in maintaining the weight loss once it is achieved. 2009 15 The Importance of Exercise The importance of exercise in aiding in weight maintenance is due to reasons discussed previously with respect to the asymmetry in appetite control, but is also due to the physiological effects of exercise in enhancing well-being and status of control, and hence compliance with a restrictive dietary regime. It is important to remember that there are many additional benefits of exercise. The benefits of exercise are not limited to just those previously discussed. 2009 16 The Importance of Exercise It is beneficial in that it: Reduces your risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, osteoporosis, diabetes, and obesity Reduces both total blood cholesterol and triglycerides and increases high-density lipoproteins, known as the “good” cholesterol. Reduces your risk for having a second heart attack Reduces your risk of developing colon cancer. Contributes to mental well-being and helps to treat depression Helps relieve stress and anxiety Increases your energy and endurance 2009 17 The Importance of Exercise It is beneficial in that it: Helps you maintain a normal weight by increasing your metabolism. (the rate in which your burn calories) Helps you sleep better. Keeps joints, tendons, and ligaments flexible so it’s easier to move around. Reduces some of the effects of aging. Helps older adults become stronger and better able to move about without falling or becoming excessively fatigued. 2009 18 Physical Activity &Coronary Heart Disease A major, underlying risk factor for coronary heart disease is inactivity. In a study published in JAMA, men, who were initially unfit and became fit, were found to have a 52% lower age-adjusted risk of cardiovascular disease mortality than their peers who remained unfit. Regular physical activity has been shown to impact blood pressure beneficially. One study found that for every 26.3 men who walked more than 20 minutes to work, one case of hypertension would be prevented. 2009 19 Physical Activity &Coronary Heart Disease It is important to note that these acute effects of exercise on blood pressure lowering do not require vigorous efforts. They can be achieved at 40% of maximal capacity during exercise. Blood lipids play a major role in the development of atherosclerosis, which is the underlying cause of coronary heart disease. Moderate to vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise training has been shown to improve the blood lipid profiles of individuals. The most commonly observed changes have been: increases in High density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL), with reductions in total blood cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), and triglycerides. 2009 20 Physical Activity and Type 2 Diabetes Physical activity is associated with: A reduced risk of type 2 diabetes Improved insulin sensitivity Glucose homeostasis From participating in physical activity 30 minutes/day, overweight subjects were able to reduce their risk of getting type 2 diabetes by 58% in a recent study. Physical inactivity has been shown to elevate the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in normalweight individuals as well. 2009 21 Physical Activity & Overweight/Obesity Physical activity appears to be an important component in weight stability for healthy individuals. In a recent study looking at the effects of physical activity on body composition in 3,853 healthy subjects between the ages of 15 and 64, it was concluded that physical activity is able to limit both fat mass and weight gain in men and women. Many studies are in agreement with one another when stating that exercise + diet lead to greater weight losses than just diet-alone. In a review of 11 studies looking at the influence of both exercise and diet on weight loss, the average weight loss of the diet-only group was shown to be 6.7 kg; whereas, the average weight loss of the diet + exercise group was 8.5 kg. 2009 22 Physical Activity & Overweight/Obesity Weight loss is not only achieved, but is also maintained through physical activity. In 2001, a study was conducted on 3000 previously obese subjects, who reported a weight loss of 30 kg, on average, which was additionally maintained for an average of 5.5 years. When looking at those who did not continue to participate in physical activity, it was found that only 9% of these participants were able to maintain their weight loss in the absence of physical activity. 2009 This further supports the importance of exercise in the prevention of weight regain. 23 Physical Activity & Overweight/Obesity The optimal amount of weekly exercise necessary to prevent weight gain is still a topic under much debate. The current recommendations include, at a minimum, 150 minutes/wk of moderate-intensity exercise, or 30 minutes a day on most days of the week (5 or more). This should be the initial targeted amount of exercise each week 2009 24 Physical Activity and Appetite Control Physical activity has the potential to adjust appetite control by: Improving the sensitivity of the physiological satiety signaling system Adjusting macronutrient preferences or food choices Altering the hedonic (pleasurable) response to food There exists a belief that physical activity drives up hunger and increases food intake, thereby rendering it useless as a means of weight control. In a recent study, researchers set out to examine this very idea. 2009 25 Physical Activity and Appetite Control Recent Findings Short term (1-2 day) and medium term (7-16 day) studies demonstrated that men and women can tolerate substantial negative energy balances when performing physical activity programs. The immediate effect of taking up exercise is weight loss. This isn't always easy to assess; however, due to changes in body composition or fluid compartmentalization that arise. Once around 30% of energy is expended in activity, food intake then begins to increase in order to provide compensation for this loss. This compensation (up to 16 days) is partial and incomplete. 2009 26 Physical Activity and Appetite Control Recent Findings Subjects have been separated into compensator and non-compensator groups. The exact nature of the differences noted in these 2 groups has yet to be determined. Some subjects performing a set routine of activities for a 14 day period showed no differences in energy intake. More studies are needed to further classify individuals who are compensators versus non-compensators and to identify the mechanisms responsible for the rates of compensation and its limits. 2009 27 Physical Activity and Osteopenia Everyday physical activity has a positive effect on skeletal mass. It has been suggested that electrical currents are developed when bone is mechanically stressed, leading to the formation of new bone. When comparing whole body, leg, and trunk body mineral densities in women who walk 7.5 miles/week versus those who walk 1 mile per week or less, women in the group with the most distance were shown to have significant increases in bone density. Normal bone 2009 Osteoporotic bone 28 Physical Activity and Sarcopenia Sarcopenia can be defined as the age- related loss of muscle mass, strength, and function. Physically active subjects aged over 65 years have a significantly higher level of lean tissue mass than sedentary participants. It has also been shown that healthy older people can safely tolerate higher intensity strength training with improvements comparable with those seen in younger persons. 2009 29 Physical Activity & Psychological Disorders Physical activity is associated with elevations in mood states and heightened psychological well-being. On the other hand, inactive persons have been shown to be 1.5 times more likely to become depressed than those who maintain an active lifestyle. Physical activity is believed to be protective against the development of Alzheimer’s disease. This is believed to be due to increased blood flow, which may in turn promote nerve cell growth. It has been suggested that people who are intellectually and physically inactive have a 250% better risk of developing the disease. 2009 30 The Truth on Exercise The bad news is that people still are not getting enough exercise. This map specifically looks at physical activity trends in women and finds that only 4 in 10 women are engaging in the recommended levels of activity. Activity has been shown to generally decrease with age, and is less common among women than in men and among those with lower income and less education. 2009 Source: CDC. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2001. 31 Photo from: http://womenshealth.gov Inactivity Inactivity leads to a loss of muscle, to obesity, and to reduced functional ability. Low physical fitness increases the risk for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and some cancers. Individuals who are physically fit can do more things, have better endurance for activities and tasks, and are healthier than individuals with low fitness. Even small increases in physical activity can make a big difference to an individual’s health. Try to incorporate small changes into your daily activities. This, in time, will gradually improve your fitness, leading to a better you. 2009 32 Physical Activity and Physical Fitness What’s the difference? Physical activity is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in an expenditure of energy. Exercise is defined as a subset of physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposeful. Physical fitness is a measure of one’s ability to perform physical activities that require endurance, strength, or flexibility, and is determined by a combination of regular activity and genetically inherited ability. Simply put, fitness is good, but physical activity is a must! 2009 33 Types of Exercise Aerobic, anaerobic, and resistance Aerobic exercise is exercise that involves Anaerobic large muscle groups (arms and legs) in dynamic activities that result in substantial increases in heart rate and energy expenditure. Aerobic Anaerobic exercise is exercise done at very high intensities such that a large portion of the energy is provided by glycolysis and stored phosphocreatine. These activities build and tone muscles, but are not as beneficial to the heart and lungs as aerobic activities are. Resistance exercise is exercise designed specifically to increase muscular strength, power, and endurance by varying the resistance, the number of time the resistance is moved in a single group (set) of exercise, the number of sets done, and the rest interval provided between sets. 2009 Resistance 34 Examples Aerobic Anaerobic Brisk walking Dancing Jogging Bicycling Skating Swimming Snow shoveling Lawn mowing Leaf raking Vacuuming Baseball Sprinting Tennis Weightlifting Leg lifts Arm circles Curl-ups Dusting Doing laundry Washing windows 2009 35 Physical Activity for Everyone Everyone can benefit in some way by regular physical activity. Whether you are trying to maintain a weight loss or just feel more energetic when you incorporate exercise into your daily activities. There are also the benefits later in life from exercising. These include reductions in the risk of developing chronic diseases and overall improvements in your quality of life. 2009 36 Who Benefits and How? Older adults: Parents and children: No one is too old to enjoy the benefits from regular physical activity. Evidence indicates that muscle-strengthening exercises can work to reduce the risk of falling and fracturing bones, and can improve the ability to live independently. Parents can help their children maintain a physically active lifestyle by providing them with encouragement and opportunities for exercise. Outings and family events are encouraged, particularly when everyone in the family is involved. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2009 37 Who Benefits and How? Teenagers: Regular physical activity improves strength, builds lean muscle, and decreases body fat. Activity can build stronger bones to last a lifetime. People trying to manage their weight: Regular physical activity helps to burn calories while preserving lean muscle mass. Regular physical activity is an important component to any weight-loss or weightmaintenance activity. People with high blood pressure: Regular physical activity helps to lower blood pressure. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2009 38 Who Benefits and How? People with physical disabilities, including arthritis: Regular physical activity for individuals with chronic, disabling conditions is important because it can help improve their stamina and muscle strength. It can also improve the quality of life by improving the individual’s ability to perform daily activities. Everyone under stress, including persons experiencing anxiety or depression: Regular physical activity has been shown to improve one’s mood, help relieve depression, and increase feelings of well-being. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2009 39 Getting Started You will first want to begin by speaking with your doctor. This is particularly important if you: Are elderly Currently smoke Have any health problems Are overweight or obese Have not been active in a while Are currently pregnant Are unsure of your health status Feel pain in your chest, joints or muscles during activity When it is okay to begin, you want to start out slowly. A good suggestion could be to begin with a 10-minute period of light exercise or a brisk walk every day. You can then gradually increase how hard you exercise for and how long. 2009 40 Ways to Improve Your Health Walking or jogging Swimming Bicycle riding Group exercises Weight-bearing exercise, such as weight lifting, resistance bands, or activities involving the whole body Stretching, such as yoga or tai chi exercises Participation in active sports, such as tennis, basketball, and soccer 2009 41 Ways to Add Activity to Your Day Park the car in the furthest spot from the entrance and walk the extra distance Get off of the bus one stop before your destination and walk Take the stairs instead of the elevator Take walking breaks during the work day Take a 10-minute walk during your lunch break Walk a dog or play outside with the kids Dance to your favorite music Use housecleaning as an exercise opportunity Ask a friend, family member, or coworker to walk with you 2009 42 Physical Activity Calorie Use Chart Activity 100 lb 150 lb 200 lb Bicycling, 6 mph 160 240 312 Bicycling, 12 mph 270 410 534 Jogging, 7 mph 610 920 1230 Jumping rope 500 750 1000 Running, 5.5 mph 440 660 962 Running, 10 mph 850 1280 1664 Swimming, 25 yds/min 185 275 358 Swimming, 50 yds/min 325 500 650 Tennis singles 265 400 535 Walking, 2 mph 160 240 312 Walking, 3 mph 210 320 416 Walking, 4.5 mph 295 440 572 The chart shows the approximate calories spent per hour by a 100, 150 and 200 pound person doing a particular activity 43 2009 Adults should strive to meet either of the following physical activity recommendations… Adults should engage in moderate-intensity physical activities for at least 30 minutes on 5 or more days of the week (CDC/American College of Sports Medicine). This 30 minutes per day can be accumulated in bouts of 10 minutes throughout the day. Adults should engage in vigorous-intensity physical activity 3 or more days per week for 20 or more minutes per occasion (Healthy People 2010) 2009 Tip: While activity at a higher intensity or performed longer does offer more health benefits, this level of activity may not be a realistic goal for everyone, at least not to start with. Again, work your way to this, slowly, by setting realistic goals for each week. 44 Moderate Intensity Activity What’s is it? This is an activity which generally causes a slight, but noticeable increase in breathing and heart rate. It may also cause light sweating. Some examples of moderate intensity activity include: Brisk walking Swimming Cycling Dancing Doubles Tennis 2009 45 Sites Exercise: A Healthy Habit to Start and Keep. Available at: http://www.familydoctor.org Exercise: When to check with your doctor first. Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.com/print/exercise/SM00059/METHOD=print Physical Activity. Available at: http://womenshealth.gov/pub/steps/Physical%20Activity.htm Physical Activity Calorie Use Chart. Available at: http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=756 The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Available at: http://www.jama.com Physical Activity for Everyone: The Importance of Physical activity. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/physical/importance/index.htm General Physical Activities Defined By Level of Intensity. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/physical/pdf/PA_Intensity_table_2_1.pdf Sarcopenia: The Mystery of Muscle Loss. Available at: http://www.unm.edu/~lkravitz/Article%20folder/sarcopenia.html Physical Activity and Weight Control. Available at: http://win.niddk.nih.gov/publications/physical.htm Aerobic or Anaerobic? Quick Activity. Available at: http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=3003065 2009 46 Sites Melzer K, Kayser B, Pichard C. Physical activity: the health benefits outweigh the risks. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care. 2004; 7: 641-47. Prentice A, Jebb S. Energy intake/physical activity interactions in the homeostasis of body weight regulation. Nutrition Reviews. 2004; 62(7): S98-S104. Blundell JE, Stubbs RJ, Hughes DA, Whybrow S, King NA. Cross talk between physical activity and appetite control: does physical activity stimulate appetite? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2003; 62: 651-661. Moore M. Interactions between physical activity and diet in the regulation of body weight. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2000; 59: 193-198. Jakicic J, Otto A. Physical activity considerations for the treatment and prevention of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005; 32(suppl): 226S-9S. 2009 47 About Our Company… The Pennington Biomedical Research Center is a world-renowned nutrition research center. Mission: To promote healthier lives through research and education in nutrition and preventive medicine. The Pennington Center has several research areas, including: Clinical Obesity Research Experimental Obesity Functional Foods Health and Performance Enhancement Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Nutrition and the Brain Dementia, Alzheimer’s and healthy aging Diet, exercise, weight loss and weight loss maintenance The research fostered in these areas can have a profound impact on healthy living and on the prevention of common chronic diseases, such as heart disease, cancer, diabetes, hypertension and osteoporosis. The Division of Education provides education and information to the scientific community and the public about research findings, training programs and research areas, and coordinates educational events for the public on various health issues. We invite people of all ages and backgrounds to participate in the exciting research studies being conducted at the Pennington Center in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. If you would like to take part, visit the clinical trials web page at www.pbrc.edu or call (225) 763-3000. 2009 48