Class Action - Northern Illinois University

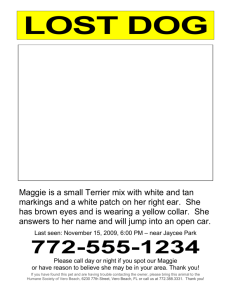

advertisement

Civil Law • • • David v. Goliath: films depicting civil disputes often show the small-time, solo-practitioner attorney taking on the big corporate law firm. We see big firms practice greedy, unethical, even illegal behavior and drag out cases to bleed their cash-strapped opponents who often work on a contingency-fee basis (they only get paid if they win). Discovery: during the pre-trial phase of a case, both sides are supposed to exchange all the information each has on the case. While this is meant to encourage settlement, it also leads to lengthy delays. Lengthy discovery is often difficult for plaintiff’s attorneys who work on contingency fees and enrich defendant’s attorneys who bill by the hour. Hence defendant’s attorneys routinely submit a blizzard of documents in hopes of overwhelming their opponents who may endlessly search in vain for the proverbial needle in a haystack. Wither Workaholics? • On one level, the film is a critique of excessive work and singleminded focus on career and is therefore critical of the corporate, getahead-at-all-costs, work ethic of the New Right political regime. • Jed’s excessive devotion causes hurt to those closest to him such as his wife Estelle and his daughter Maggie as well as his friend Tagalini. • Maggie’s desire to climb the corporate ladder and make partner leads her into an unhealthy relationship with a co-worker and make poor career choices in the end. • In this sense, Jed and Maggie are not the opposites they seem to be at first blush (liberal v. conservative; plaintiff v. defendant; big firm v. small). The are exactly the same in their focus on career at the expense of everything else. Ethics • What should Maggie have done when she discovered that Michael destroyed Pavel’s report? • She could tell her clients about the consequences of destroying evidence and urge them to supply another report to opposing counsel, consistent the discovery requirements. • She could urge her clients to settle the case immediately to avoid a big loss at trial. • She could tell the judge what happened. • She could report the actions of her superiors to the state bar association’s ethics committee. • She could take herself off the case. • She could leave the firm. • In the end, she chooses to betray her clients by telling opposing counsel what she knows and undertakes a legal strategy that harms her clients and her firm. • In the process, she betrays client loyalty and will probably be disbarred for violating legal ethics. Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio as Maggie Ward • • • • • • • • • • • She is a new San Francisco corporate attorney climbing the ladder to a coveted partnership. In order to get there, she believes that she has to exhibit phallic power and dominance. To show sympathy for victims and concern for family would be to exhibit “weak,” liberal, female traits. As a result, she is miserable and makes bad personal and professional decisions. Of course her superiors know that she will overcompensate for this and they assign her the job of defending the automobile corporation against injury claims. She formally opposes her father in a class action lawsuit and is ordered by her unethical male superior and lover, Michael, to “play ball” in order to win the case, which he knows she will do. Maggie’s main concern, however is her father and in a classic feminist position, she conflates the public and private behavior of her father: “You’re a user, Dad. You used Tagalini [a corporate whistleblower]. You used all those women, and you used Mom.” She also conflates the public and private by sleeping with her boss, Michael. Nick (Lawrence Fishburne), at attorney in Jed’s firm has her completely figured out: “Your biggest aspiration is to be his mirror image—exactly the opposite of what he is. And the problem is, you don’t know what he is. That makes being you impossible.” Maggie is caught in the classic father-daughter Electra (Oedipal) complex of female sexual development: She kills her mother so that she can replace her in a relationship with the father. But which “father” will she choose? The image or the mirror-image? She MUST choose, however, in order to “find herself” as a daughter, woman, and lawyer. Why? Because the feminist position leaves her unsatisfied (indeed it’s excessive and fueled by her own insecurities), is antithetical to the corporate environment she works in, and is inconsistent with her father’s mainstream liberal position. Female Attorney Protagonists • Like many of her predecessors in the female attorney films before Class Action, such as Jagged Edge, Suspect, Music Box, and The Big Easy, Maggie is caught within a web of deception constructed by the male characters surrounding her. • Maggie is being used not only by Quinn but also by her lover Michael, several other male associates, and later Jed, though this time in the name of justice. Father #1: Gene Hackman as Jedediah Ward • Former activist lawyer in the 1960s and 1970s from the People’s Republic of Berkeley, he represents victims and their families seriously injured or killed in car accidents involving a defective model. • He is the “good” father of corporate attorney Maggie Ward. • However, his focus on career and fame led to affairs and the ultimate failure of his marriage and family life. Maggie resents him for the affairs and thinks he is still at it at the party when she thinks she sees him hitting on a young associate. As in Adam’s Rib, the associate is a lesbian and therefore the scene only serves to clarify the relationship between the main characters. • Jed plays the role as mediator (father) for Maggie’s agency (daughter) in personal, professional, and ethical terms. • He represents the mainstream liberalism of Bill Clinton and other Democrats attempting to operate in the New Right (conservative) political regime. Father #2: Donald Moffat as Fred Quinn • Controlling partner of the corporate firm where Maggie works. • He is the “bad” father to Maggie, seducing her into the high-powered, prestigious, rich, corporate, legal world. • Quinn represents the New Right conservatism of the Reagan/Bush I-era when the film was made. • Moffat made a career of playing attorneys, even the senior partner, in films like Regarding Henry. Cinematic Techniques • Mise-en-scene combines with parallel editing in the first third of the picture to function as a barometer of Jed’s politically correct position, against which the film asks us to evaluate Maggie. Jed speaks of “justice” while Maggie argues the “law.” • Numerous courtroom sequences portray Maggie as the castrating female. With shots composed so that the jury often is visible, we watch as one elderly male juror, positioned on the far right of the frame, lowers his head in embarrassment and sympathy with Dr. Pavel when Maggie attacks his credibility. This shot, along with several others in which we see Jed’s reaction from a distance, once again defines Maggie as a threatening figure. • Maggie’s imposing class-and-steel firm where lawyers compete for fast-track cases in contrasted with the warm, homey, small office of Jed and Nick where they democratically discuss the rights and safety of “the people.” Maggie’s Choice • • • • • • • Why don’t either Maggie or Jed move toward the mediated position represented by their martyred mother/wife Estelle? Female lawyer films routinely set-up dichotomies that the female protagonists must resolve: public/private; reason/emotion; law/justice. This suggests a lack of empowerment as the female must conform to one stereotype or the other. Before ultimately aligning herself with the “proper” patriarch, Maggie threatens to subvert justice because she is a public agent of law and reason—as good as any man can do. Yet she never has any real choice because the numerous exchanges between her two fathers demonstrate that men ultimately wield the real power. Only when she embraces the film’s liberalism does Maggie achieve a coherent subjectivity in service to her good father, the film’s true agent of justice. The picture’s Hollywoodland, happy-ending final shot is telling: the Oedipal/Electra embrace of her good father is familiar and comforting to both them and us. When she refused to dance with him earlier in the film we were upset! Now, everybody’s happy! Female Lawyer Films • • • • • • There was a huge explosion of female lawyer films in the 1980s and 1990s. Why? Hollywood films in general from this period illustrate a crisis of maleness and patriarchy. One example is the use of female protagonists in increasing numbers—even in action pictures such as Aliens and Point of No Return. Films involving law, and particularly women lawyers, provide unique opportunities to question patriarchy: male v. female attorney with “the law” (patriarchy) in dispute. Yet these films ultimately undermine the feminist critique of patriarchy. How? The female lawyer is often positioned to deflect the very analysis of patriarchal power her existence would seem to prompt: the female lawyer herself is “put on trial” so to speak, and we question her role as a woman and a lawyer. Indeed, continually reminding us that patriarchy and the law are inseparable, almost all female lawyer films feature patriarchal figures who possess the potency—the genuine power—to initiate the female lawyer into he structure of the law, to deny her access, or to regulate her behavior as she performs within or outside the courtroom. These men, the films suggest, rightfully “own” the power of language and the law. The Paradox • Hence the paradox: the existence of a female lawyer is a powerful feminist critique on patriarchy, however her ultimate inability to “measure up” and her choice between either the “good” or “bad” father-figures competing to influence her, exposes a lack of agency and deeply conservative, antifeminist underpinnings. • Radical feminism is co-opted, watered-down, and replaced by a “new woman” or “corporate feminism” which equates liberation from patriarchy with enlistment in its ranks—in one form or another. • Female lawyer films, therefore, become symptomatic of the very crisis they wish to submerge. Credits • • • • • Bergman, Paul and Michael Asimow, “Class Action,” in Reel Justice (Kansas City: Andrews and McMeel, 1996) 171, 176, 198, 233. Lucia, Cynthia, Framing Female Lawyers: Women on Trial in Film (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2005). Ryan, Michael and Douglas Kellner, Camera Politica: The Politics of Ideology of Contemporary Hollywood Film (Bloomington, IA: Indiana University Press, 1988). Sklar, Robert, Movie-Made America: A Cultural History of American Movies, rev. ed. (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1994). Tushnet, Mark, “Class Action: One View of Gender and Law in Popular Culture,” John Denvir, ed., Legal Reelism: Movies as Legal Texts (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1996) 244-60.