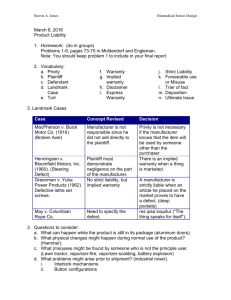

Power Point Chapter 19

advertisement

CHAPTER 19 Product Warranty Warranties & Product Liability Product Liability (Tort) • Based on: – Negligence – Misrepresentation • Requirement for Strict Liability Express Warranty • Warranty = Contractual promise by seller regarding quality, character or suitability of goods sold • Creation of Warranty/Guarantee – – – – Specific words or intent not required Statement of fact or promise Concerning the goods Which becomes a part of the bargain • Question 2 at end of chapter – The court found that in agreeing to produce crystal balls conforming to the prototype sample approved by the testing laboratory, Plastic had created an express warranty that its product would conform to the sample. It breached that warranty when the production balls had thinner walls that differed from the prototype sample and would not pass the safety test. Beck v. Plastic Products Co., Inc., 412 N.W.2d 315 (Ct. App. Minn. 1987). Express Warranty • Creation of Warranty/Guarantee – Advertisements • Bobholz v. Banaszak, p.321 – Where the seller in one advertisement described a boat as being in “perfect condition’, in another ad described it is as “in excellent condition”, and represented to the potential buyer in a conversation that the boat had been properly maintained and winterized in the previous year, that statements were held to constitute express warranties. The statements were affirmations of fact relating to the goods and the representation regarding the quality of the boat was a basis of the bargain because it induced the buyer to purchase the boat. Note what the plaintiff must show in order to be able to recover on a theory of breach of express warranty, namely show that the statement was an affirmation of fact relating to the goods and that the representation was a part of the basis of the bargain because it induced the buyer to purchase it. Express Warranty • Creation of Warranty/Guarantee – Not Mere Opinion/Puffery • Question 1.Yes. The statements in the leaflet constituted descriptions of the capabilities of the product and were not mere puffing. The product was purchased—and used— in reliance on those statements. They constituted an express warranty, and the failure of the product to conform to the representations was the cause of Klages’s injury. Klages v. General Ordnance Equipment Corp., 19 UCC Rep. 22 (Super. Ct. Pa. 1976). Express Warranty • Creation of Warranty/Guarantee – Advertisements • Question 1 at end of chapter – Yes. The court held that the statements in the advertisements could create express warranties but that they had to be shown to be part of the “basis of the bargain” on which Cippolone had purchased the cigarettes. Thus (1) Antonio Cipollone had to prove that his wife had read, seen or heard the advertisements in question and (2) Liggett had to have an opportunity to prove that any advertisements read, seen, or heard by Cipollone were not believed by her. Cipollone v. Liggett Group, Inc., 893 F.2d 541 (3rd Cir. 1990). Implied Warranty • Nature - Imposed by Law • Merchantability- Fit for Ordinary Purpose – – – – Conform to promises or statements of fact made on label Adequately Packaged/Labeled Same Kind/Quality/Quantity w/I each unit Fungible (Mixed Goods that cannot be separated, e/g. coal), of average quality – Acceptable in trade or business Implied Warranty – Denny v. Ford Motor Co., p.323 • Where the manufacturer designed a vehicle for off-road use— but marketed and sold it knowing that most buyers intended to use in for on-road driving—and the vehicle had a propensity to roll over when used on the highway, the manufacturer was held liable for breach of the implied warranty of merchantability on the grounds it was not fit for the ordinary purpose for which it was intended. • Would the result have been different in this case if the product had been marketed solely as an off-road vehicle? What if had been marketed only as an off-road vehicle and it rolled over while being used off-road? Implied Warranty – Mexacali Rose v.Superior Court, p.324 • Where a customer in a Mexican restaurant was injured by a chicken bone contained in a chicken enchilada that he purchased, the court majority applied the foreign-natural test and held that if an injury producing substance is natural to the preparation of the food served, then it can be said that it was reasonably expected and the food cannot be considered unfit or defective. A minority of the court dissented, stating that no reasonable consumer would anticipate finding the bone. The minority would have applied the reasonable expectation test. Implied Warranty – Klein v. Sears Roebuck & Co., p.325 • Where the buyer explained to the seller his particular needs concerning a lawnmower and relied on the seller’s recommendation as to the appropriate model that would be suitable for his needs, the seller made an implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose which was breached when the mower proved to be unsuitable for the buyer’s needs and he was injured as a consequence. • Note the dual requirements that must be met for the implied warranty of fitness for a particular purpose to be created: the seller must know the particular purpose for which the buyer needs the goods and that the buyer is relying on the seller to select goods suitable for Implied Warranty – Example: Marino v. Perna. • This case involves two separate sales of a 1981 Oldsmobile. In the first sale of the vehicle at an auction conducted by the Marshall of the city of New York, the sale was considered to be out of the ordinary course of business and carried no warranty of title. However, when the buyer at the auction resold the car to a co-worker, the sale did carry with it an implied warranty of title. Implied Warranty – Example: Under the Code, if the seller of goods is a merchant with respect to goods of that kind, a warranty of merchantability is implied in the contract of sale. To be merchantable, the goods must be at least fit for the ordinary purposes for which they are sold and conform to any promises or affirmations of fact made on the container or label. When a product fails to meet the reasonable expectations of the user, it can be inferred that there was some sort of defect that breached the warranty. A thermos bottle that implodes or explodes when coffee and milk are poured into it is defective. Virgil v. “Kash N’ Karry” Service Corp., 484 A.2d 652 (Ct. App. Md. 1984). Implied Warranty – Question 4 at end of chapter • No. The court adopted the reasonable expectation test and held that a jury could reasonably find that because the nature of the food was a hamburger (which is not usually eaten with a knife and fork), the restaurant customer should not reasonably have anticipated the presence in it of a bone particle. Mitchell v. BBB Services Co., Inc., 582 S.E.2d 470 (Ct. App. Ga. 2003). Implied Warranty – Question 5 at end of chapter. • Yes. Where the seller at the time of contracting has reason to know the purpose for which the goods are required, and that the buyer is relying on the seller to furnish goods that are suitable for that purpose, a warranty of fitness for a particular purpose arises. The glasses were advertised as suitable for use by baseball players and were bought and used for that purpose. The buyer relied on the seller’s assurance that the glasses were suitable for baseball playing. In fact, they were not. The lenses were so thin that they shattered into exceedingly sharp splinters when broken. Since they lacked the safety features of plastic or shatterproof glasses, they were not fit for baseball players. Filler v. Rayex Corp., 435 F.2d 336 (7th Cir. 1970). Implied Warranty – Question 6 at end of chapter • Yes. The court found that under Section 2-312 of the UCC, a merchant selling goods warrants that he is passing clear title to the goods. Williams breached that warranty of title when he sold the stolen camera to Brooke because a thief cannot pass clear title to goods, nor can his successor. It is irrelevant that Williams did not know the goods were stolen. The court also found that there was no effective disclaimer of the warranty of title through the placing of “as is” signs in the store. Brooke v. Williams, 766 P.2d 1311 (Sup. Ct. Mont. 1989). Implied Warranty – Bryant v. Hoffman-La Roche, Inc., p. 330 • Where a patient was given some free samples of medicine that the manufacturer had provided to her physician, the patient was not entitled to the benefit of the implied warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose because there was no privity between the patient and the manufacturer. Note that if the doctor had provided the medicine to someone in his family or who was a guest in his home, the warranties would be available to the recipient of the medicine. Implied Warranty – Question 3 at end of chapter • Yes. the court held that Eveready breached the implied warranty of merchantability when it produced batteries that leaked battery fluid on the consumer’s ankle. The batteries were subject to the warranty, they were defective at the time of sale because when they were put to their intended use they malfunctioned, and the injury was due to their defective nature. DeWitt v. Eveready Battery Co., Inc., 565 S.E.2d 140 (Sup. Ct. 2002). Exclusions/Modifications • General Rules – Parties have right to agree to – Courts frown on seller self-limits • Limitation of Express Warranty – Disclaimers must not be inconsistent with – Thacker v. Menard, p.327 • Where a written estimate clearly disclaimed any warranty that the materials were fit for any purpose, even if a contract was formed, it did not include any such warranty. Exclusions/Modifications • Exclusion of Implied Warranty – For merchantability • Must specifically mention merchantability • If in writing must be conspicuous – For Fitness for Particular Purpose • Must be in writing and conspicuous – Or by conditions of sale (e.g. “as is”) • Unconscionable Disclaimers – Courts may not enforce • Limitation of Warranty – May limit nature of liability Who May Sue? • Old Rule: Privity of Contract Required • Current trend: Suits allowed against manufacturer Who May Sue? • Old Rule: Privity of Contract Required • Current trend: Suits allowed against manufacturer – Question 8 at end of chapter • In Re air Crash Disaster at Sioux City, Iowa on July 19, 1989 / Banks v. United Airlines, Inc. – A passenger on an airplane that crashed was not in privity of contract with a supplier of a component part to the aircraft and thus not able to assert a claim for breach of warranty of fitness for a particular purpose. The court declined to extend to an injured passenger the warranty protection the California legislature had given to an injured employee. FTC Warranty Rules • Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act (1975) – Purpose of Act • Provide Minimum Warranty Protection for Consumers • Increase Consumer Understanding of Warranties • Ensure Warranty Performance by Providing Meaningful Remedies • Encourage Better Product Reliability FTC Warranty Rules • Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act (1975) – Requirements • Seller must: – – – – – – – I.d. who can use the warranty Must clearly describe goods covered by the warranty Must state nature of remedy(ies) Must state duration of warranty Must explain process for initiating a claim Must state any exclusions Must inform as to possible legal variances FTC Warranty Rules • Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act (1975) – Full Warranty • • • • • • Fix or replace Not limited in duration Not limit consequential damages Refund option if can’t repair/replace No unreasonable duties on consumer Notify of exclusion where improper use FTC Warranty Rules • Magnuson-Moss Warranty Act (1975) – If Not Full = Limited Warranty – Availability of Warranty • In writing, before sale – Enforcement • FTC enforces disclosures Negligence • Types – Improperly Manufactured – Misrepresented – Failure to Disclose/Warn/Instruct Known Defects • Question 10 at end of chapter. – No. The court held that under the circumstances Honda satisfied its duty to warn under the law of strict liability and negligence. It was not necessary to warn of every conceivable danger that could be encountered if the user rode the bikes on public highways. The boys were old enough to read and to comprehend the warning they were given. Baughn v. Honda Motor Co., Ltd., 727 P.2d 655 (Sup. Ct. Wash. 1986). Negligence • Types – Failure in Design Due Care • Weigl v. Quincy Specialties Company, p. 334 – Where a lab coat marketed for that purpose had a tendency to melt and fuse to the user when exposed to a flame, burned much more readily than lab coats manufactured by other companies, and the coat contained no warning as to its flammability characteristics, a person who was badly burned while wearing the coat was entitled to recover on the theories of defective design, negligent-testing, failure to warn, and breach of warranty. Negligence • Types – Failure in Design Due Care • Question 9 at end of chapter – Griggs v. BIC Corp., p.270-271 » Where a three-year-old child started a house fire with a disposable lighter that seriously injured his younger brother, the manufacturer of the lighter was potentially liable for negligence for failing to manufacture a childproof lighter. The court found that it was foreseeable that a lighter might fall into the hands of a child who, although not the intended user, could ignite it with the risk of serious injury to himself and others. Note that the court found that strict liability was not applicable. Could a case be made that strict liability should be applicable to lighters? Negligence • Types – Failure in Design Due Care • Example: In designing a product, the manufacturer has a duty to design it so that it is reasonably safe in light of the risks of injury that can be foreseen. A risk is not foreseeable where a product is used in a manner that could not be reasonably anticipated. The purposes of an automobile trunk are top transport, show and secure the spare tire, luggage, and other goods, and to protect them from the weather. The dimensions of a trunk, the height of its sill and load floor, and the effort required to lower the trunk lid and then to engage its latch are among the design features that encourage closing and latching it from the outside. Its design makes it almost impossible for an adult to intentionally enter the trunk and close the lid. Use of the trunk as a means to commit suicide was unforeseeable and the manufacturer had no duty to design the trunk in light of this risk. Manufacturers also have no duty to warn of a risk that is unforeseeable. In addition, they have no duty to warn of duties that are obvious. In fact, Daniell initially took that risk. Finally, the potential efficacy of a warning, given Daniell’s use for a deliberate suicide attempt, is questionable. Daniell v. Ford Motor Co., Inc., 581 F. Supp. 728 (D.N.M. 1984) Negligence • Types – Failure in Design Due Care • Example: Commonly there are three types of product defects that may give rise to a claim that a manufacturer of a product should be liable in strict liability: (1) a flaw in the manufacturing process resulting in a product that differs from the manufacturer’s intended result; (2) products that are perfectly manufactured but are unsafe because of the absence of a safety device, that is a defect in design; and (3) products that are dangerous because they lack adequate warnings or instructions. Here, the claim is based on an asserted failure of the dangerous propensities of Halcion that were known or scientifically knowable. The California Supreme Court has held that a drug manufacturer may not be held strictly liable for failure to warn of a drug’s inherent risks where it neither knew nor could have known by the application of scientific knowledge available at the time of distribution that the drug could not produce the undesirable side effects suffered by a plaintiff. The court was concerned that unless limited, strict liability might make drug companies reluctant to undertake the risks of developing and marketing beneficial new drugs. Accordingly, it set forward the following statement of the law: A manufacturer is not strictly liable for injuries caused by a prescription drug so long as the drug was properly prepared and accompanied by warnings of its dangerous propensities that were either known or scientifically knowable at the time of distribution. Accordingly, Carlin should be given an opportunity to show that the alleged side effects were known or knowable at the time she purchased the drug and that she was not given suitable warning concerning them. Carlin v. Superior Court of Sutter County, 38 Cal. Rptr.2d 576 (Ct. App. Cal. 1995). Negligence • Obvious Danger Defense – Not a complete defense, but a factor • Privity/Disclaimers Not Apply Strict Liability • Elements – – – – – Sold in defective condition Unreasonably dangerous Product of type seller normally sells Received in unaltered condition Consequential harm Strict Liability • State Of The Art-Dangerous or Defective – What known that could have been done to make safer? – Uniroyal Goodrich Tire Co. v. Martinez, p.336 • The manufacturer was held strictly liable for injuries caused by the plaintiff’s failure to follow a suitable warning where the manufacturer was aware of a safer tire design but had not utilized in the design of the tire that caused the injury. Strict Liability • Industry-wide Liability (e.g. asbestos) • Statutory Limitations • Statutes of Repose (like statute of limitations) Elements Strict Liability • Defective Condition or Unreasonably Dangerous • Selling Engaged in Selling Product • Reach Consumer Without Change • Harm/Damage From Condition Defenses- Strict Liability • Assumption of Risk • Nonforeseeable Product Misuse • Contributory/Comparative Negligence