Africans in America: America's Journey Through Slavery

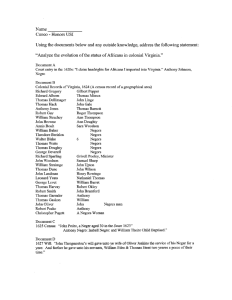

advertisement

“Truth it is that through our long peace and seldom sickness…we are grown more populous than ever heretofore; so that now that there are…so many, that can hardly live by one another,…yea many thousands of idle persons are within this realm.” Richard Hakluyt, “A Rationale for New World Colonization” According to Captain John Smith, Jamestown was a “ ‘fruitfull and delightsome land’ where “‘heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for mans habitation.’” Cited in Davidson, “Serving Time in Virginia”, p. 7. “As described by historian Abbot Emerson Smith, they included convicts, ‘rogues, vagabonds, whores, cheats, and rabble of all descriptions, raked from the gutter,’ ‘decoyed, deceived, seduced, inveigled, or forcibly kidnapped and carried as servants to the plantations.’ They were regarded as the ‘surplus inhabitants’ of England.” Ronald Takaki, A Different Mirror, p. 54 “In sum, this enterprise [Jamestown] will minister matter for all sorts and states of men to work upon;…yea, old folds, lame persons, women, and young children, by many means…shall be kept from idleness, and be made able by their own honest and easy labour to find themselves without surcharging others.” Richard Hakluyt, “A Rationale for New World Colonization” According to Captain John Smith, Jamestown was a “ ‘fruitfull and delightsome land’ where “‘heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for mans habitation.’” Cited in Davidson, “Serving Time in Virginia”, p. 7. In 1607, 120 colonists arrived in Jamestown and according to the charter granted to them by King James, their mission was to “ ‘first to preach and baptize into the Christian religion… and recover out of the arms of the Devil a number of poor and miserable souls.’ ” Charles Johnson and Patricia Smith, Africans in America: America’s Journey Through Slavery, p. 29 According to Sir Walter Raleigh, “‘I never saw a more beautiful country, nor more lively prospects…the plains adjoining without bush or stubble, all fair green grass,…the air fresh with a gentle easterly wind, and every stone that we stooped to take up, promised either gold or silver.’” Cited in Charles Johnson and Patricia Smith, Africans in America: America’s Journey Through Slavery, p. 31. “Criminals escapes the gallows by signing up. In some instances, innocent people were accused of crimes in order to force them into indentures. People were kidnapped, plied with alcohol. Children were offered sweets.” Charles Johnson and Patricia Smith, Africans in America, p. 34. John Rolfe writing to Sir Edwin Sandys: “About the latter end of August, a Dutch man of Warr of the burden of 160 tunnes arriued at Point-Confort…He brought not any thing but 20 and odd Negroes, wch the Governor and Cape Marchant bought for victualle (whereof he was in greate need as he pretended) at the best and easiest rate they could.” Engel Sluiter, “New Light on the ‘20 and Odd Negroes’ Arriving in Virginia, August 1619”, p. 395-6 Captain John Smith writing in the Generall Historie of Virginia, “Nay so great was our famine, that a salvage we slew and buried, the poorer sot tooke him up again and eat him; and so did divers one another boyled and stewed with roots and herbs:…” Charles Johnson and Patricia Smith, Africans in America: , p. 32. TREATED EQUALLY/ COMMON INTERESTS “Slavery or modified slavery was a distinct possibility for all disadvantaged people—Indian as well as black and white immigrants. So to was open society. Socioeconomic forces…tobacco…and capitalist planting techniques based on the use of gang labor tilted the structure in the direction of Negro slavery.” Lerone Bennett, Confrontation: Black and White “Virginia legislated against intermingling in 1662, 1691, 1696, 1705, 1753, 1765. There were similar paroxysms in other states.” Lerone Bennett, Confrontation: Black and White “White and black, they shared a condition of class exploitation and abuse; they were all unfree laborers. Sometimes they had to wear iron collars around their necks. When they were recalcitrant, they were beaten and event tortured. They were required to have passes whenever they left their plantations. White and black, laborers experienced the day-to-day exhaustion and harshness of work.” Ronald Takaki, A Different Mirror, p. 55. “A white servant in Virginia was undoubtedly expressing the anguish of many laborers, whether from Europe or Africa, when he wrote: ‘I thought no head had been able to hold so much water as hath and doth daily flow from mine eyes.’” Ronald Takaki, A Different Mirror, p. 55. “Their status as free men was always in danger of debasement: planters bought, sold and traded servants without their consent, and on occasion they even used them as stakes in gambling games. There had been ‘many complaints,’ acknowledged John Rolfe, ‘against the Governors, Captaines, and Officers in Virginia: for buying and selling men and boies,’ something that ‘was held in England a thing most intolerable.’” Davidson, “Serving Time in Virginia”, p. 16 “One Englishman put the indignity quite succinctly: ‘My Master Atkins hath sold me for a £150 sterling like a damnd slave.” Davidson, “Serving Time in Virginia”, p. 16 Elisabeth Key was ½ English and ½ African. She was a servant to an Englishman from 1636-1645 (9 years) and a servant to another Englishman, John Mottrom until 1655. In 1656, she sued for her freedom claiming her father was free, she “was sold for 9 years” [implication that it’s an indentured servitude contract] and that she was Christian. [Court recognized her ability to sue.] Court ruled she was free. After an appeal, she was denied her freedom. The General Assembly investigated and her owners dropped their opposition and she was declared free. William M. Billings, “The Case of Fernando and Elizabeth Key” “…‘Antonio, a Negro’ is listed as a “servant” in 1625 census.” “…court records in 1641 indicate that Anthony was master to a black servant, John Casor.” “In 1645, a man identified as ‘Anthony the negro’ stated in court records, ‘now I know myne owne ground and I will worke when I please and play when I please.’” By 1650, the Johnsons [Antony and his wife Mary] owned 250 acres of land that they got through the headright system. Charles Johnson and Patricia Smith, Africans in America: America’s Journey Through Slavery, p. 38-39. “Land patent granted to Anthony Johnson, on 250 acres for transport of five persons…” Virginia Land Patent Book No. 2, p. 326,24 July 1651. 3 indentured servants of Hugh Gwyn: Victor the Dutchman, James Gregory the Scotsman and John Punch the Negro. They ran away from their master together. They all “shall receive the punishment of whipping and to have thirty stripes apiece.” Then Victor and James Gregory owe the colony 3 years after their service is done but John Punch, the Negro, must serve for the rest of his life. H[enry] R[ead] McIllwaine, ed. Minutes of Council and General Court of Virginia… “Court records indicted repeated instances of blacks and whites conspiring to escape together. In one case, the Virginia court declared, ‘Whereas [six English]…Servants… and Jno. A negro Servant…hath Run away and Absented themselves from their…masters Two months, It is ordered that the Sherriffe…take Care that all of them be whipped…and Each of them have thirty nine lashes well layed on…” Ronald Takaki, A Different Mirror, p. 55 1661 law—if you run away from your master, you owe him double the time of your indenture. If you are English and you run away with a Negro and the Negro dies, you will have to pay the Negro’s master 4,500 in tobacco or 4 years of service. Statues 2:116-117 “White and black, Bacon’s solders formed what contemporaries described as, ‘an incredible Number of the meanest People,’ ‘every where Armed.’ They were the ‘tag, rag, and bobtayle,’ the ‘Rabble’ against ‘the better sort of people.’” Ronald Takaki, A Different Mirror, p. 64 Negro women’s children retain the status of their mother. December 1662, Act XII Servants cannot go abroad without a license. September 1663, Act XVIII