The Case of the Monkey

advertisement

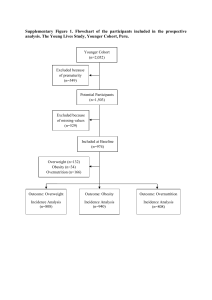

Parenting and Obesity Julie C. Lumeng, MD University of Michigan Center for Human Growth and Development Department of Pediatrics Obesity Trends* Among U.S. Adults BRFSS, 1985 (*BMI ≥30, or ~ 30 lbs overweight for 5’ 4” woman) No Data <10% 10%–14% 1990 No Data <10% 10%–14% 1995 No Data <10% 10%–14% 15%–19% 1997 No Data <10% 10%–14% 15%–19% 20%–24% 1999 No Data <10% 10%–14% 15%–19% 20%–24% 2002 No Data <10% 10%–14% 15%–19% 20%–24% ≥25% 2005 No Data <10% 10–14% 15–19% 20–24% 25–29% ≥30% Increase in Child Overweight Prevalence, % Increase in Obesity Prevalence 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 15 11 5 1960's 1988-94 Year 1999-2000 Increase in Rates of Overweight in Children by Race Over 10 Years Increase in Child Obesity by Race Prevalence, % 25 African American 20 Hispanic 15 White 10 5 1986 1998 Year Strauss RS, Pollock HA, Epidemic increase in childhood overweight, 1986 – 1998. JAMA 286(22). 2845-2848, 2001. Increase in Child Overweight by Race and Socioeconomic Status Increase in Child Obesity by Race and Socioeconomic Status Prevalence, % 30 Low income African American and Hispanic boys 25 20 15 Upper income white girls 10 5 0 1986 1998 Year Strauss RS, Pollock HA, Epidemic increase in childhood overweight, 1986 – 1998. JAMA 286(22). 2845-2848, 2001. US Obesity Prevalence by Race and Age, 2003-2006 30 23.8 % obese 25 21.3 20 15 14.9 16.7 15.0 10.7 10 5 0 White Black Mexican American 2-5 years White Black 6-11 years Ogden et al, High Body Mass Index for Age Among US Children and Adolescents, 2003-2006 . JAMA. 2008;299(20):2401-2405. Mexican American Overweight Prevalence in Preschoolers and Poverty 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 White Boys White Girls Black Boys NHANES (national data) Black Girls Hispanic Hispanic Boys Girls Head Start (children in poverty) M Feese et al. Prevalence of Obesity in Children in Alabama and Texas Participating in Social Programs. JAMA 289. 1780 – 1781; 2003. Etiology of Overweight Calories taken in exceed calories expended • Institute of Medicine, Committee on Childhood Obesity: Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance – A National Priority – Industry, advertising, media – Local Communities – Schools – Home “Expert Committee Recommendations for Parents” • • • • Limit consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages Encourage diets with recommended quantities of fruits and vegetables Limit television and other screen time by allowing no more than 2 hours per day Remove television and computer screens from children's primary sleeping areas MM Davis, Pediatrics 2007 “Expert Committee” Recommendations for Parents • • • • • • • Eat breakfast daily Limiting eating at restaurants Have family meals Limit portion sizes Have an authoritative parenting style Avoid a restrictive parenting style Model healthy behaviors MM Davis, Pediatrics 2007 Watching Television 10 8.8 Percent overweight 9 8 7 6 5.6 5.8 1.75 - 3 3 - 4.9 5 4 3 2.0 2 1 0 <1.75 > 4.9 hrs/day Hours per day of television JC Lumeng, et al. Television Exposure and Overweight Risk in Preschoolers Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:417-422. Which Children Watch More TV? • • • • • • • • • Low maternal education Minority race/ethnicity More televisions in the home More eating meals while watching television TV in the bedroom Maternal depression Maternal obesity Child behavior problems Low quality home environment Saelens 2002. J Dev & Behav Pediatrics; Burdette 2003. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med; Certain 2002. Pediatrics; Dennison 2002. Pediatrics; Lumeng 2006. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. Safety of the Neighborhood 18 16.8 Percent Overweight 16 14 11.5 12 10 8 6 4.1 4 2 0 Safest Average Safety Least Safe Perception of Neighborhood Safety Relationship not altered by child’s sex, race, maternal marital status, maternal education, maternal depression, the child’s participation in structured after-school activities, parental perception of neighborhood social cohesiveness, quality of the home environment JC Lumeng et al., Neighborhood Safety and Overweight Status in Children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:25-31. Who Feels Unsafe in Their Neighborhood? • Parents of African American children (as opposed to parents of white children), regardless of socioeconomic status • Mothers who are depressed, have low education, and are single Feeding and Parenting Parenting Behavior Impacts How Much Children Eat from Infancy • 8- to 14-week-old infants who are provided social interaction while feeding eat 40% more than those who are not provided social interaction • Infants who are held while fed closely relate the time elapsed since the last feeding to the amount they eat; when infants are not held, this relationship dissipates Lumeng, Patil, & Blass, Developmental Psychobiology, 2007. Behavior Problems Predicting Childhood Obesity • National Longitudinal Survey of Youth • N = 629 non-obese children, ages 8 – 11 years – 53% male – 53% white – 9% with behavior problems • Tested relationship between baseline “significant behavior problems” and becoming obese 2 years later • Tested potential confounders: – child’s sex – Race – mother’s marital status – mother’s education – family poverty status – mother’s obesity – mother’s depressive symptoms – Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment-Short Form (HOME-SF) cognitive stimulation score – mother’s smoking status – use of behavior-modifying medication – hours of television per day – history of academic grade retention Odds ratios for childhood obesity 2 years later Covariate Behavior problems (yes v no) OR (95% CI) 5.23 (1.37 – 19.93) Race Black v. white Hispanic v. white Quality of home environment 1.82 (0.79 – 4.24) 5.47 (2.18 – 13.7) Low v. high Medium v. high Baseline BMI z-score 2.43 (0.31 – 18.7) 4.10 (0.52 – 32.4) 5.86 (2.43 – 14.12) JC Lumeng et al. Association Between Clinically Meaningful Behavior Problems and Overweight in Children. Pediatrics (112). 1138-1145. 2003. Which children are at higher risk for behavioral problems? • • • • • Poverty Single mother Grade retention Low maternal education Maternal depression JC Lumeng et al. Association Between Clinically Meaningful Behavior Problems and Overweight in Children. Pediatrics (112). 1138-1145. 2003. Media Response • “Isn’t it all just bad parenting?” • “I've long suspected that rapidly growing rates of childhood obesity in the United States may be tied, at least in part, to the fact that American children in general seem more out of control and ill-behaved than ever. And that that's because their parents seem more ineffective and less likely to tell their children "no" than ever. You've seen it. The screaming, crying, foot-stomping little kids yelling at their parents and making demands in the mall, the grocery store, and virtually every restaurant one enters. It is not particularly surprising kids try that stuff -what's stunning is watching the impotent, terrified parents looking like deer caught in headlights as it's happening.” – one journalist Affect Regulation, Food, Mood, and Parenting • Children with behavior problems, difficult temperaments more likely to be overweight • Children who have tantrums over food more likely to become overweight • Food regulates affect (cortisol, stress axis) • Use of food to regulate mood in parents and children • “Food is love” The Parent-Child Interaction What Everyone Needs from Relationships • To feel known and understood • To feel “chosen” • To experience a balance of giving and getting What Everyone Needs from Relationships • To feel safe to be yourself and to explore options for change • To be able to predict the reactions of the other • To experience conflict cooperatively Parenting Style Parenting Style and Childhood Obesity • NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development • N = 872 children in 1st grade – 49% male – 83% white – 11% obese • Maternal sensitivity (scored from videotaped standardized interaction, “supportive presence”, “respect for autonomy”, “hostility”) • Maternal expectations for self-control Maternal Expectations for Self-Control How often do you expect your child to (1) Sit or play quietly (or refrain from interrupting) while adults are having a conversation? (2) Be agreeable about an unexpected change in plans? (3) Accept a new babysitter or caregiver without complaint? (4) Be patient when trying to do something difficult? (5) Go to bed without a hassle? (6) Refrain from interrupting when you are on the telephone? (7) Show self-control when disappointed? (8) Stay in bed once put to bed? (9) Be on "best behavior" when you are in public? (10) Wait his or her turn without fussing? (11) Control anger outbursts? Potential Confounders • • • • • Race Maternal education Income-to-Needs Ratio Family Composition (single mother v. not) Child behavior problems (Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist) Odds ratios for child being obese in first grade Covariate Self-control (high v. low) Sensitivity (high versus low) Gender (male versus female) Race (white versus other) Maternal education Income/needs ratio Living with spouse or partner Child behavior problems OR (95% CI) 1.27(0.82–1.96) 0.47 (0.28–0.81) 1.23 (0.81–1.92) 1.54 (0.82–2.94) 0.98 (0.88–1.09) 0.92 (0.83–1.02) 0.97 (0.49–1.96) 1.01 (0.99–1.04) Authoritarian 20 Neglectful 15 17.1 % obese Permissive 10 5 9.9 9.8 Authoritative 3.9 0 Low Expectations for Self-Control Low Sensitivity High Expectations for Self-Control High Sensitivity *Adjusted for income-to-needs ratio and race K Rhee, JC Lumeng, et al. Parenting Styles and Overweight Status in First Grade. Pediatrics (117). 2047-2054. 2006. Media Response • “Strict Parenting Raises Risk of Childhood Obesity” • “How Parents Mold Their Children’s Weight” (NYT) • “Do Very Strict Parents Raise Fat Kids” (CBS) • “Insensitive Parents, Chubby Children” • “Study: Mean, Maniacal Mom Made you Fat” • “It’s All Our Fault Anyhow” Why? • • • • Supporting response to satiety? Supporting physical activity? Affect regulation? Stress? Sleep and Childhood Obesity: Does “Poor” Parenting Explain the Link? • NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development • N = 785 children in 6th grade – 50% male – 81% white – 18% obese • Sleep duration by maternal response to Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire Potential Confounders • • • • Gender Race Maternal education Child Behavior Checklist, internalizing and externalizing subscale scores • Parenting measures – CHAOS Scale – Mid-Childhood Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (quality of the home environment) – Greenberger's Raising Children Checklist, lax control subscale Odds ratios for child being obese in 6th grade Covariate OR (95% CI) Sleep duration in 3rd grade,h 0.60 (0.36–0.99) Change in sleep duration 0.68 (0.44–1.06) between 3rd and 6th grades, h Gender (male versus female) 0.82 (0.40–1.71) Race (white versus other) 1.42 (0.54–3.73) Maternal education 0.84 (0.72–0.99) BMI z score at 3rd grade 127.4 (48.0–337.8) JC Lumeng, et al. Shorter Sleep Duration Is Associated With Increased Risk for Being Overweight at Ages 9 to 12 Years. Pediatrics (120). 1020-1029. 2007. Is it All Just “Bad Parenting”? Covariate OR (95% CI) CHAOS Score 0.98 (0.92 – 1.04) Quality of Home Environment 1.01 (0.97 – 1.05) Lax Control Subscale 0.99 (0.93 – 1.05) Beliefs about Childhood Obesity Among Low-Income Mothers • • • • • • N = 91 Ages 3-5 years Children: 21% obese, 26% overweight Mothers: 49% obese, 41% overweight 41% of mothers < high school education 26% of families food insecure “Why are children obese?” • I definitely blame overweight children on the parents. One hundred percent. I think it’s because they’re not educated, because they don’t know any better, because they’re feeding them things that are making [them] overweight and not giving them a healthy diet. Um, too much fast food. Um, a lot of parents just don’t care. I mean, honestly, there’s a lot of parents that just don’t care. Some parents feed their kids fat and let them be lazy in front of the TV all day, every day. I think children are overweight because of parents neglecting to do their jobs the way that they should, and [not] caring about their weight and their health. • There is people that, like the women that work here a lot, sometimes can’t take care of their children and when they take care of them, they are not used to making them something to eat, then they take them to those restaurants and I think that that makes you gain weight a lot. • So, I see a lot of kids that have, a lot of mothers that have heavy-set kids and they just…just because they’re hungry…they just ate two cheeseburgers…you know, just because they hungry you don’t have to feed them. And they’d say never turn down a child to eat. Yeah, I think you do. You just don’t feed your kid every time they’re hungry. • The mothers give them Twinkies, candy and ice cream and -- everyday, this is an everyday thing -- cookies and, you know, to me that’s what causes a child to be overweight. In every nursery there are ghosts. They are the visitors from the unremembered past of the parents. While no one has invited them, they take up residence and conduct the rehearsal of the family drama. In healthily developing relationships, the parents can move the ghosts aside to be present for the child. Selma Fraiberg, 1980 “How were you fed as a child?” • When I was a kid we didn’t have dinners. “Here’s a hot dog. Here’s a sandwich. Eat it.” You know? Not with me and my daughter. I make dinner. I don’t throw a hot dog at her and say, “Here you go. Eat that. You’re good.” No. I don’t do that. wish things would have been different for me, but it wasn’t. • My parents were actually very strict so dinner was somewhat stressful. We were expected to use our manners and, like, we weren’t allowed to drink while we ate. You couldn’t sit and slug down your glass of milk. You had to either sip it or it was taken away from you. Um, we had to clean our plates and it didn’t matter portion size, whatever, you had to eat everything that was on your plate. • I spend a lot of time with my kids and we eat together and my dad never did that, so, um, we do eat together and I do cook a little bit. But I always make sure my kids have breakfast, lunch, and dinner. My dad never did that. He just --- fend for yourself, really. I make sure that they eat and I make sure that we eat together. • My dad raised me by himself. Um, and he had a gambling problem. There was a bar just down the road. So, from like, ten and up, um -- I don’t remember much from ten and down -- I fed myself. Parenting and Obesity Maternal Feeding Behaviors Conceptualizations of Maternal Feeding Behaviors (1) along a continuum of more or less controlling (which may encompass both pushing and restricting intake) (2) 2 separate domains of prompting versus restricting (3) 4 parenting styles: authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and indulgent What is the “Right” Way to Feed? • Prompting to eat associated with: – Thinner child – Heavier child – No relationship • Controlling and restrictive feeding practices associated with: – Heavier child and increased caloric intake in unrestricted settings – Thinner child – No association • Allowing children more choice in what to eat – Heavier child – Thinner child – No relationship overweight and high restriction normal weight and low restriction Δ normal weight and high restriction ▲ overweight and low restriction O overweight and high restriction ● LL Birch et al, Am J Clin Nutr, 2003. Differences in Reported Feeding Practices by Income Low-income minority mothers (compared to upper-income white mothers) self-reported: • • • • • • • Greater concern about their infant’s hunger Using food less often to calm their infants More scheduled feedings Greater difficulty feeding their preschoolers Pushing their preschool children to eat more More divergent feeding practices Less mealtime structure at toddler/preschool age Baughcum 2001. J Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics Differences in Feeding Practices by Race • Hispanic parents have been described as self-reporting a more indulgent or permissive feeding style. • African American parents self-report a more authoritarian (directive) feeding style. • Hispanic parents self-report more controlling practices in their feeding than do African American parents. Effect of Maternal Feeding Behaviors May Differ By Maternal Weight Status • In children of obese mothers, more prompting to eat familiar foods was inversely associated with higher child BMI. • In children of non-obese mothers, prompting to eat was not associated with the child’s BMI. JC Lumeng et al, J Pediatrics, 2006. Predictors of Observed Maternal Feeding Behaviors • NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development • N = 734 mother-child dyads at age 3 years • Videotaped while eating standardized snack • Maternal behavior coded: – intrusiveness (1 to 4, higher scores = more intrusiveness) – total prompts to eat (defined as verbal encouragements, physical encouragements, and food offers) • Multiple regression predicting each Multiple regression predicting each feeding behavior Covariate Sex (Female v. Male) Race (white v.not) Maternal Education Maternal Depression Maternal Weight Status Child Overweight v. Not Child obese v. Not * p<.05 Intrusive β (SE) -.16 (.06)* .17 (.08)* -.03 (.01)* .01 (.00) .01 (.02) .20 (.09)* .17 (.12) Prompts β (SE) -.52 (.40) -1.15 (.54)* -.31(.08)* .06 (.03)* .30 (.14)* .25 (.61) .42 (.85) Conclusions • Obesity is tough to prevent and treat, and will require interventions on multiple different levels (community, school, home) • Parents play an important role, but the dyadic interaction needs to be considered (i.e. innate child behavioral predispositions likely bring something to the situation) • The jury is still out on which specific feeding practices and behaviors should be recommended Food for Thought: Maternal Beliefs about Feeding in Low-Income Groups Low Income African American Mother In response to: Do you worry about having enough food at the end of the month? Sometimes, sometimes. Yea, sometimes. I run low on food and I don’t have the type of food that I normally give them, you know? As long as I got some sandwiches they’re happy, you know? Cause, see, when it’s not nothing and she’s like, ‘Momma I’m hungry. I’m hungry,’ then it worries me. Like my mother always said, you always got food when you got canned goods in your cabinet, you know? I had to take all the canned good down, open them up, mix them all together and come up with something a couple times. Everybody looked at it ‘What’s that, momma?’ ‘I don’t know baby. It’s something. We need something to eat and we going to eat whatever it is. You got to eat it.’ You know, and they try it and they like it. It’s then when I go to other peoples’ houses and they’re down low—they have less than what I had to make what I got. He got to have a hotdog. And then I always wonder, them hotdogs, they’re not filling him up. He can eat three or four, but he has always ate three or four hotdogs behind each other, but it’s just that I be wondering if that is enough.” And then when I don’t have no hotdogs and can’t get no hotdogs and having a hard time trying to figure out what [my son] is going to eat. You know, because I got to make sure I got something that he will eat, cause if it’s not nothing he’s guaranteed to eat then I start wondering ‘Dang, my baby’s losing weight. My baby’s not this, my baby’s not that.’ You know.” All I can ask for is just something for him. Just give me some hotdogs and some bologna—just give me that. As long as my baby can wake up to a hotdog and go to bed to a hotdog, I’m happy. It may not be healthy for him, but . . . you know. Low Income Hispanic Mother To feed them, you have to do it with love. Because if you do it when you are in a bad mood or tired, they won’t even eat. The most beautiful thing is that you always give them [food] with love and with that desire -- that you know that you are feeding them and that you know that its your responsibility to feed your children. You should do it with lots of care, lots of love and to always try to think that they are being fed by you and that you have to give them the best that you can -- with patience -because sometimes [they say] “I don’t want this”, [and I say], “What do you want, mijo? If you didn’t like the food today, what do you want?” You have to give them with patience and with love because it is very hard sometimes. One is trying to understand all of them [her children].