Critical-reading-pack-for

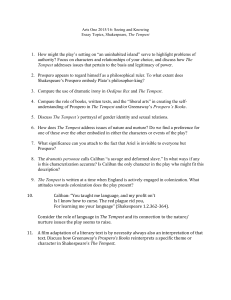

advertisement

Year 13 – critical material on The Tempest Please bring to every lesson (Or risk the wrath of Prospero… see above) Conjuring up a storm Authority and leadership in The Tempest Exploring The Tempest in the social and political context of Jacobean England leads Neil Bowen to read it ‘as a coded, but nevertheless daring critique of Jacobean ideology.’ In the opening scene Shakespeare brilliantly uses the resources at his disposal to conjure a storm. Whereas in a modern film CGI can be used to create a storm scene, in The Tempest Shakespeare only has words, the stage and perhaps music. This means he has to work much harder than, say, a modern film director to make the audience imagine the storm. How then does Shakespeare do this? The situation is, of course, dramatic. The ‘ship’ is being split apart and the social order thrown into confusion. Shakespeare uses sound effects – ‘a tempestuous noise of thunder and lightning’ – to convey this confusion. But the pace of the dialogue is more important. Shakespeare wants us to believe these characters are in mortal danger, hence the dialogue cuts urgently from one agitated character speaking to another. Generally the lines are also very short, often consisting of just a few words: Do you hear him? You mar our Labour. Keep your cabins. (Lines 12-13) The rhythm created is suitably swift and choppy. Tone is also crucial in creating the drama. Normally, in Shakespeare’s plays, we expect lowly characters to address Noblemen with respect. Indeed at the end of the play that is how the Boatswain addresses his ‘betters’. In this crisis, however, the Boatswain is exasperated by the Noblemen’s interference with his attempts to save the ship. And when he cries, ‘What cares these roarers for the name of King?’ he openly challenges the authority of the King and the Court. The challenge is underscored by a series of commands, ‘Hence...To cabin. Silence! Trouble us not’. The language here is sharp and stark. The air crackles with sedition. Shakespeare then ratchets up the tension through the Noblemen’s enraged response; Sebastian curses ‘a pox o’ your throat’, and Antonio spits ‘Hang, cur, hang you whoreson, insolent noisemaker’. Later in the scene we will also hear desperation, ‘lay her a-hold’, and despair, ‘Mercy on us! We split, we split’. The situation is extreme and the relationships between the characters are violent and stormy. For an audience, confusion is also created by the simple fact that the characters are not named. Shakespeare’s usual marker of social status – verse for the nobility, prose for the plebeians – is, as elsewhere in the play, also scrambled. A profusion of entries and exits punctuates the stage action. Look, for instance, at lines 4, 8, 26, 32, 36, 49 and 63. Together these devices create a pervasive sense of tension, confusion and disorder. In short a tempest is conjured. The Great Chain of Being For a Jacobean audience the opening of The Tempest must have been even more disorientating. The dominant model of social order was ‘The Great Chain of Being’, a rigid, pyramid-like structure within which all things had their rank. In the spiritual sphere, God was at the apex and underneath him were ranked various types of angels. The earthly world reflected this divine pattern; the Monarch sat at the tip of the pyramid, on top of the Aristocracy; the Aristocracy looked down on the teeming merchant classes and, down at the foot were the masses, the peasants; the whole weight of the structure upon them. A key aspect of the ‘Great Chain of Being’ was that it was sanctioned by God. Hence seeking to change social position, or worse, questioning the authority of those above you, was seen, not just as questioning your betters (which could be dangerous enough) but also to be going against God himself. The fear of threats to this rigid, top-down structure is clear in, for example, the Sumptuary Laws or the 1598 Poor Law Act. The Sumptuary Laws controlled the dress code at court. The wealthier and more powerful you were the more colours, patterns and fabrics you were allowed to wear. The Queen could wear ermine, for example, whereas the Nobles were allowed fox. The Poor Law Act made it legal to beat and drive from a parish ‘masterless men’, i.e. those that did not fit into the ‘Great Chain of Being’. A scene where the normal hierarchy is so confused would therefore be dangerous and alarming. Authority in tempest Shakespeare’s bold opening raises serious questions about leadership and authority. In a crisis, authority appears to lie with those able to deal best with the situation. It is the boatswain who wields power in this scene, as indicated, for instance, by his domination of the lines. The Noblemen are at best ineffectual; at worst an encumbrance. They shout at their potential saviour, and generally get in the way. The Boatswain’s cry challenges the authority of the King and suggests that monarchy (and by implication ‘The Great Chain of Being’) is not natural, or God-given. Instead it is an unnatural construct. And one which, crucially, is vulnerable to outside forces. The ‘roarers’ are these forces rising. They are loud and violent – hence ‘roaring’ – and ready to mount a challenge. Later in the play these rebellious forces will be represented, in comic form, by Trinculo, Stephano and Caliban, and in more sinister form by Antonio and Sebastian. The Tempest can be seen, then, as exposing fault lines in the seemingly impregnable social order. Thirty or so years after the play was written, of course, these ‘roarers’ did become so powerful and insistent that a Civil War would break out, a King be beheaded and the new social order of the ‘Commonwealth’ established. So from the very opening of the play questions of power, leadership and authority are raised. As in Shakespeare’s history plays, much of the rest of the action in The Tempest wrestles with these key ideas. Prospero’s lessons in leadership Traditional interpretations of The Tempest have often seen the play as obliquely criticising King James; advising him on good government. In this reading Prospero is identified with the King and is shown, over the course of the action, to learn how to be a better leader. If this is the case what does he learn about leadership and authority? In Act 1 Scene 2 Prospero tells the audience he lost his dukedom because he was too trusting (of his brother, Antonio) and became too absorbed in his studies to rule effectively, ‘rapt in secret studies’, ‘neglecting wordly ends’. On the island he suffers for his mistakes, and has to learn the values of patience and fortitude. At the end of the play he breaks his magic ‘staff’ and ‘drowns’ his books. Thus, as his increasingly Christian language indicates, he gives up his role of magus and dedicates himself to conscientious government. Moreover, though Prospero may have intended to revenge his usurpation, by punishing his brother Antonio and Alonso, in the end he refrains. Despite having all his enemies at his mercy, prompted by Ariel ‘...if you now beheld them, your affections/ Would become tender’ (Act 5 Scene 1) he forgoes the satisfaction of vengeance. He learns, instead, the value of mercy and the virtue of reconciliation. He is ready by the end of the play to reassume his previous role, but now as a wiser, more responsible leader: ‘the rarer action is in virtue than in vengeance’. And so The Tempest ends with order emerging from disorder; the ‘roarers’ reconciled by Prospero’s justice. After the storm has passed, the Boatswain returns in Act 5, humble and deferential; Ariel is finally freed. Gonzalo’s exclamations set the tone in his celebration of the engagement of Ferdinand and Miranda: O rejoice Beyond a common joy, and set it down With gold on lasting pillars. In one voyage Did Claribel her husband find at Tunis, And Ferdinand, her brother, found a wife. Alternative readings But this traditional reading marginalises aspects of the play which do not fall so neatly into its comforting scheme. Troubling questions persist: is Claribel’s marriage, for instance, really a cause for such celebration? Did Ferdinand really ‘find’ Miranda? What justification is there for Prospero’s usurpation of the island? Postcolonial writers, in particular, have highlighted the problems with the simple equation underpinning traditional readings of The Tempest, i.e. Prospero = noble and civilised; Caliban = savage and uncivilised. Taking their lead from the postcolonialists, modern critics emphasise the ways in which the play questions the basis of Prospero’s power and authority. Far from presenting Prospero as learning Humanist values, they argue, he is an altogether more sinister character. A subtle, but arch Machiavellian, the former Duke stagemanages the action in order to regain power, using his daughter as part of his political game, trampling on those who do not fit into his scheme. Certainly, as the opening scene shows, conventional ideas are questioned by the play. Gonzalo’s speech on a commonwealth, for example, provides an alternative model of society organised on an egalitarian basis. This utopian vision is juxtaposed with the cut-throat opportunism of Sebastian and Antonio. Moreover, Shakespeare shows how the political system depends on the subjugation of women – both Claribel and Miranda are used for geo-political gain by their fathers, and Sycorax is demonised by Prospero. However, it is the presentation of Caliban that most persuasively points to the play as a coded, but nevertheless daring critique of Jacobean ideology. Caliban, the hero As many critics have noted, Caliban is given verse, not prose, and this can be moving and beautiful. See for example the speech beginning, ‘The isle is full of noises/Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not...’ Furthermore, Caliban’s ability to recognise the beauty of music shows a potentially civilised sensibility, in contrast to Antonio and Sebastian, for instance, who are deaf to Ariel’s music. Another stark contrast is between the tender wonder of Caliban’s words and the brutal language Prospero uses against him. The tirade of abuse against Caliban (‘Hag-seed’, ‘malice’, ‘this thing of darkness’) echoes Antonio and Sebastian’s cursing of the Boatswain in the opening scene, and Prospero’s bemonstering of Caliban, are also undercut by the visceral descriptions of his physical suffering. Caliban’s cry of ‘This island’s mine, by Sycorax, my mother’ raises issues about authority and colonialism that Prospero and his sympathisers would rather avoid. The ending The end of the play does not provide a simple return to social order; the rainbow Prospero produces for the Masque is an illusion only. Although Prospero seems to have gained just authority, and although characters are back within their proper place in ‘The Great Chain’, the ending is undermined by unresolved doubts about the treatment of Caliban and of Ariel. Moreover, the silence of Antonio suggests that the forces of discord, the potential ‘roarers’ have not yet been properly reconciled. The manipulation of Miranda and her evident naïvety are also troublesome: How beauteous mankind is. O brave new world That has such people in’t. Modern critics argue that the ending does not neatly resolve the play’s issues. Instead they are left open and urgent. The play presents an ambiguous picture of colonialism and of the position of women in society. The play questions the features of a good society and the basis and nature of just authority. It shows how power can be generated, used and abused. In troubled times especially, such as during a tempest, it challenges us to consider what constitutes good, responsible, wise leadership. Neil Bowen This article first appeared in emagazine 35. Claribel’s story The Tempest Richard Jacobs argues that The Tempest is haunted by the absent Claribel and her forced marriage. Claribel? Who’s she? Don’t worry too much if that’s your first response to my title. Claribel doesn’t get widely discussed in criticism of, and commentary on The Tempest. One reason for that is that the play itself passes over her, and her story, in a rather perfunctory way. But I think she has important things to say about the play. Claribel is one of a number of women who are both in and not in the play. That is, like Sycorax and Mrs Prospero, as Carol Ann Duffy would call her, Claribel is talked about but doesn’t appear on stage. (Is The Tempest the only Shakespeare play to feature just one woman in the stage-action?) All three of these talkedabout women, incidentally, do actually appear in Peter Greenaway’s remarkable film Prospero’s Books and Mrs Prospero even gets allocated a name (but I’ve forgotten it). Claribel’s story is told in Act 2 Scene 1 when Gonzalo tries gamely, and much to the contemptuous amusement of Antonio and Sebastian, to cheer up Alonso. Gonzalo is struck by the odd fact that, despite being ‘drenched in the sea’ during the shipwreck, all their garments are ‘as fresh as when we put them on first in Afric, at the marriage of the King’s fair daughter Claribel to the King of Tunis’. After three attempts to draw Alonso’s attention to this fact, he gets this suddenly angry response: You cram these words into my ears against The stomach of my sense. Would I had never Married my daughter there! For, coming thence, My son is lost and, in my rate, she too, Who is so far from Italy removed I ne’er again shall see her. Alonso is certain that he’s lost Ferdinand to the seas, a wound into which Sebastian then pours some rather unbrotherly salt. Sir, you may thank yourself for this great loss, That would not bless our Europe with your daughter, But rather lose her to an African… You were kneeled to and importuned otherwise By all of us; and the fair soul herself Weighed between loathness and obedience at Which end o’th’beam should bow. Later in the scene, after Ariel has put the rest of the court party to sleep, Antonio tempts Sebastian with his assassination plot on the grounds that Claribel, after Ferdinand, the next heir of Naples, now ‘dwells/Ten leagues beyond man’s life’ and therefore can’t possibly pose any threat to their plans. And that’s the Claribel story. She’s only mentioned once more, in the play’s last moments, when Gonzalo remarks on the marvel that: in one voyage Did Claribel her husband find at Tunis, And Ferdinand her brother found a wife Where he himself was lost. What do we make of this? One point to start with is that Claribel’s marriage is a forced marriage. It’s made quite clear that it was only her ‘obedience’ to her father that outweighed her ‘loathness’, her dislike of the marriage and the husband. This is the tyrannical father imposing his will on his daughter, as threatened (but not fulfilled) in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The next point is that everyone else in the court of Naples objected to the marriage as well, though not it seems out of sensitivity to Claribel’s feelings: the Napolitans’ objections were racist, opposed to Alonso’s plans to ‘loose her to an African’ rather than to a European. I’m struck by the word ‘loose’, as if Claribel is being seen as a bit of sweet white meat to be tossed to a wild black animal. There’s also a submerged pun on ‘lose’ (Alonso loses daughter as well as son). Polonius uses the word in an equivalent context when planning to use Ophelia as decoy or bait with Hamlet: he tells Claudius that when Hamlet is next seen reading in the lobby ‘at such a time I’ll loose my daughter to him’. So why does the marriage happen at all? The play is silent on this but the answer is clear: Claribel is forced into a marriage with the King of Tunis for reasons of geo-politics and/or trade. Claribel is the commodity or prize (or bait) in an act of commercial-colonial calculation over Africa. And the reason the Neapolitan court party is now on Prospero’s island is that they were on their way back to Naples after the marriage in Tunis. Even Alonso himself, faced with the presumed death of his son, seems to regret his actions with his daughter, who is now ‘so far from Italy removed/I ne’er again shall see her’. And it’s very remarkable that Gonzalo forces us to think again about Claribel’s situation at the very end of the play. Yes, ‘in one voyage/Did Claribel her husband find at Tunis’. But is that a happy ending, for her? Why is all this important? One answer is that, in this very highly patterned play, we’re being invited, if only part consciously, to see Claribel as a version of Miranda. At first the differences seem clear: Miranda loves Ferdinand and Ferdinand is Italian and the marriage is not forced. But it is nonetheless an arranged marriage – Prospero very deliberately manipulates his daughter into making it possible – and it’s also an important dynastic marriage that politically consolidates the relations between two Italian city-states, though with the odd effect, as critics have pointed out, of consolidating and extending the power of Naples over Milan. The Claribel story, then, gives a muted ironic edge to the Miranda story, making us uneasily recognize that Miranda too is a commodity. It also has an effect on the way we perceive Caliban. If the King of Tunis is the unwelcome black suitor whom the white bride tries to resist, then that’s the Caliban story told in a different way as well. Miranda is able to resist successfully and her father stigmatizes and punishes the transgressor; Claribel is not able to resist and her father delivers his daughter into the black embrace. The King of Tunis becomes the son-in-law; Caliban is the son that Prospero can only unwillingly ‘acknowledge mine’. The Claribel story both sharpens the racist representation of loathsome Africa, home to Sycorax and Caliban, and also underlines the questionable morality of Prospero’s European colonizing power over Caliban, equivalent to Alonso’s ambitions with Tunis. Another pattern positions Claribel as one of three virtuous white women – Miranda, Claribel and Mrs Prospero, described as a ‘piece of virtue’ (‘piece’ means masterpiece) – who collectively thus further demonise Sycorax as the ‘dark’ or ‘other’ woman and mother. One other effect of the Claribel story is odd. It undermines Prospero’s authority and stage-management. In the first scene he explains to Miranda that ‘by accident most strange, bountiful Fortune… hath mine enemies/Brought to this shore’. But it’s not an accident at all: it’s Alonso’s decision to impose the King of Tunis on his daughter that has brought Prospero’s enemies to this shore. Moreover, Prospero, who apparently knows everything, shows no awareness or knowledge of the Claribel story. The effect of this is to cast another ironic note, one that makes Prospero, in this matter at least, less often ‘all-powerful authority’ and more ‘victim of circumstance’. And it’s that way of thinking about Prospero that I find most helpful. For all his stage-management he’s the victim of one crucial circumstance above all: the fact that his daughter has grown up and he has to lose/loose her to another man. And he can’t do anything about it. His ignorance of the Claribel story is an emblem of that inability. The play explores most subtly in the area of father and daughter and that’s why the Claribel story is so important. From the play’s first moments – and twice in one speech – we can hear a father trying to tell his daughter that she must now at last know him properly, now before it’s too late. In what I take to be a very poignant pun, though I don’t think I’ve seen it commented on elsewhere, Prospero says ‘Tis time/I should inform thee farther’ and, ten lines later, ‘Sit down. For thou must now know farther’. Richard Jacobs This article first appeared in emagazine 28 April 2005 Clothing in The Tempest 'Rich garments, linens, stuffs and necessaries' Roy Booth looks at the motif of costumes and clothing and reveals how the characters’ changing wardrobes signal the importance of Prospero as controller of others, as well as key shifts in characters’ roles. In the will which he signed on March 25th 1616, among other bequests, Shakespeare left his sister Joan twenty pounds ‘& all my wearing Apparrell’. Clothes were important to Elizabethans both as items valuable in themselves (and hence this legacy to a relative who couldn’t actually wear the garments bequeathed to her), and, inseparable from their value, as indications of social status. An actor and dramatist would always have had a special awareness of the contribution of clothing to identity. You will most likely be aware from other texts how important costumes are in Shakespearean drama – all those disguises in the comedies, the ‘borrowed robes’ of Macbeth, the ‘lendings’ King Lear frantically discards. The Tempest continues this attention to clothing, both in major aspects of the play, and in some of its more puzzling details. Prospero’s Robes This short investigation will start with the most obvious special costume of the play, addressing first the question of what Prospero looked like when wearing his ‘Art’. (The Folio text of The Tempest always gives ‘Art’, meaning magic robes, a capital A.) The critic Keith Sturgess envisaged a cloak covered with cabbalistic symbols. This is possible, but William Davenant, an early fan and imitator of Shakespeare (he carried his fandom so far that he was happy to allege that he was Shakespeare’s son) wrote a masque in which, ‘Merlin the Prophetic Magician’ enters apparel’d in a gown of light purple, down to his ankles, slackly girt, with wide sleeves turned up with powdered Ermines, and a roll on his head of the same, with a tippet hanging down behind, in his hand a silvered rod (Britannia Triumphans, 1637) Davenant copied Shakespeare so programmatically that this may involve a recollection of Prospero. Either way, it’s important that we see that Prospero is able to take off his magical ‘Art’ like a lab coat: magic has not taken him over. The moments when he coerces Ariel send the same message: Ariel is not an evil spirit serving Prospero for his own ends, but has to be forced to serve. Prospero is in control of his magic; it isn’t a black magic in charge of him. Trinculo’s Clothes, Caliban’s Gaberdine Another occupational costume in the play is that of Trinculo, who – although he is only a ‘dull fool’ (Act 5 Scene 1 line 297) – ought to be in a jester’s costume (hence Caliban’s ‘pied ninny’ insult in Act 3 Scene 2 line 62). Trinculo is our witness for what Caliban wears: My best way is to creep under his gaberdine … under the dead mooncalf’s gaberdine for fear of the storm (Act 2 Scene 2 lines 38-9 and 111-3) Caliban, whose only mentioned garment is his ‘gaberdine’, is, of course, Prospero’s sartorial opposite. In the latest Arden text we read that a ‘gaberdine’ was ‘a long loose cloak for men made of coarse cloth'. Its simplicity contrasts with Prospero’s and the court party’s finery. David Lindley, editing the New Cambridge text, more imaginatively compares it with the ‘Jewish gabardine’ worn by Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, suggesting that Shakespeare uses such a cloak as ‘an outsider garment’. An early dictionary by Thomas Blount (1661) defined a ‘rochet’ as a ‘loose Gaberdine, or gown of Canvas, worn by a labourer over the rest of his clothes’, while in a little play by Phineas Fletcher (1631), a ‘gaberdine’ seems to feature as something a fisherman would wear – and that’s appropriate, for Caliban is regularly associated with fishiness and fishing. Unlike Blount’s labourer, Caliban might be near-naked under a canvas cloak. He is certainly barefoot (hence the painful effectiveness of the hedgehogs Prospero’s spirits will spitefully put in his path). Prospero’s Changes of Costume While Caliban has his one unchanging garment, Prospero himself frequently changes his attire. In the nearcontemporary play by Ben Jonson, The Alchemist, Captain Face, dealing with the many clients of the alchemist Subtle, wishes for a suit of clothes – ‘To fall now like a curtain, flap’ (The Alchemist, Act 4 Scene 2). Quick-change artists still perform their strenuous and stylised routines (you can find clips on YouTube). But Prospero is in a way a slow-change artist: Lend thy hand, And pluck my magic garment from me. So, lie there, my Art - Act 1 Scene 2 lines 23-5 I am ready now - Act 1 Scene 2 line 187 Ariel sings, and helps to attire him … So, so, so - Act 5 Scene 1 line 87 sd; 96 Besides fussing reverently over the robes of his ‘Art’, over the course of the action, he slowly, reluctantly, changes one role and costume (Magus) for another (Duke of Milan). At the end of The Tempest, Caliban comes to a new perception of Prospero, who has by then resumed the clothing he wore as Duke of Milan: Ariel, fetch me the hat and rapier in my cell; I will discase me and myself present As I was sometime Milan - Act 5 Scene 1 lines 83-6 Trinculo says, ‘If these be true spies which I wear in my head, here’s a goodly sight’, and Caliban agrees: ‘O Setebos, these be brave spirits indeed! How fine my master is!’ (Act 5 Scene 1 lines 259-262). Caliban as ‘savage’ (Act 1 Scene 2 line 357) was always likely to be deployed in a late moment of endorsement like this. But consider the restless and unappeased Prospero, hander-out of costumes, fusser about his own, assigner of roles. Dressed up again in his ducal hat, flourishing his ducal rapier (‘these seem rather basic signs of ducal authority’, as David Lindley rightly says), presenting himself as he formerly appeared, Prospero is effectively a pretender to his own former dukedom, dressing up as he had appeared 12 years before to convince people he’s the same man. Though Caliban is impressed, these tokens of semiroyal substance seem rather too close to the callow aspirations Antonio uses to spur on Sebastian (‘My strong imagination sees a crown/Dropping upon thy head’, Act 2 Scene 1 lines 202-3), even to the ‘trumpery’ which distracts Stephano and Trinculo (Act 4 Scene 1 line 186). Can Prospero really relinquish his ‘Art’ for such rather ordinary regalia? Restitution to Former Position Using clothing as a motif, the play works rather hard to make restitution to a previous state something remarkable and worthwhile. Alonso’s entourage should be imagined as very well dressed. They first wore their present garments at the wedding of Claribel, from which they were returning. In Act 2, Gonzalo insensitively reiterates his fascinated observation that despite having been in the sea, all their garments seem ‘rather new-dyed than stained with salt water’ (Act 2 Scene 1 lines 61-2). This is as Ariel affirmed to Prospero (Act 1 Scene 2 line 218), the boatswain later affirms the same thing has happened for the rest of the crew (Act 5 Scene 1 line 236). Gonzalo just can’t get over it: ‘Methinks our garments are now as fresh as when we put them on first in Afric […] we were talking that our garments seem now as fresh as when we were at Tunis […] Is not, sir, my doublet as fresh as the first day I wore it?’ (Act 2 Scene 1 lines 66-7; 92-3; 989). The clothes carry some symbolic weight of restitution and restoration, but the human loss seems far greater, both here (for Alonso believes that he has lost a son and cannot be expected to find much comfort in this recompense that excites Gonzalo so much), and in Prospero’s brief swagger as restored Duke of Milan (and self-deposed man of Art). Delusions of Grandeur If in this case clothes seem inadequate to suggest a rejuvenation that’s stronger than a sense of loss, clothes and costuming make other potential contributions to meaning. From beneath Caliban’s gaberdine, Stephano pulled a fool in his fool’s pied costume. Stephano has delusions of grandeur, and a clothes-conscious Prospero easily subverts his drunken conspiracy. Despite Caliban’s warnings (‘it is but trash’, Act 4 Scene 1 line 224), the butler and the jester are distracted by the ‘trumpery’ Prospero had put out for them. That misfiring set of jests about the jerkin being above or below the ‘line’ may just be drunks finding something funny which isn’t, but it is obvious that stealing ‘glistering apparel’ (Act 4 Scene 1 line 193 sd) and a befuddled conspiracy to become king go together. Stephano and Trinculo succumb to more disasters, so that ‘at the play’s end […] they stand forlorn in their muddied finery’, as David Lindley puts it. The clothing they had stolen came from Prospero. A clever production might costume the two as parodic versions of Antonio and Sebastian, two more characters who must surrender signs of status to which they have no proper claim. They must confront a fool and a deluded drunk as mirrors of their own real status. ‘Look how well my garments fit upon me,/Much feater than before’ Antonio had bragged, in a Macbeth-like moment (Act 2 Scene 1 lines 267-8). He deserves to see the same style of garments on a butler who steals the wine, or a fool who isn’t even funny. A Full Wardrobe ‘Look what a wardrobe here is for thee!’ was Trinculo’s exclamation to Stephano (Act 4 Scene 1 line 223). Prospero’s desert island is anomalously full of costumes (though as Katherine Duncan-Jones says, with its store of glistering apparel, twanging instruments and elaborate props the island is ‘an image of the playhouse and its backstage equipment’). We even see Prospero hand out a costume solely for his pleasure – with it goes a command to be invisible: ‘go make thyself like a nymph of the sea […] go take this shape/And hither come in’t’, Act 1 Scene 2 line 301; 304-5). We learn, because the play is attentive to explaining such things, that it was Gonzalo who placed ‘rich garments, linens, stuffs, and necessaries’ (Act 1 Scene 1 line 164) in the leaky boat aboard which Prospero and his daughter were to be cast adrift. That the old counsellor anticipated the future needs of the infant Miranda, and also equipped the exiles with the ‘glistering apparel’ and ‘trumpery’ doesn’t bear much realistic examination. Freeing Yourself from a Role In Shakespearean tragedies, saying farewell to your crown, or the armour you fought in (as Mark Anthony does) can be a terrible moment of loss. But in The Tempest, a play where kings ‘fade […] into something rich and strange’ in the sea’s unfixed element, where actors are spirits who vanish, Prospero’s last three words are ‘set me free’. He has learned from Ariel the desire to be unfixed, neither pegged into a tree, nor a costume. Stage directors have to make up their minds about what to do with Caliban at the end. A.D. Nuttall suggests that Caliban expects to be retained in service and leave the island with his master. More romantic stagings leave Caliban alone on the island. Prospero broke his staff and buried it; he drowned his grimoire, his book of magic. But aren’t we fairly sure that he leaves his ‘Art’ to Caliban, and that our last vision ought to be of Caliban, out of his gabardine and wrapped in purple splendour? Dr Roy Booth is a senior lecturer at Royal Holloway College, London University. He specialises in the literature of the 16th and 17th centuries. This article first appeared in emagazine 57, September 2012. Caliban: On the Edge of Humanity When Trinculo first encounters Caliban in in Act II, scene 2 of The Tempest he says “what have we here? A man or a fish?” Caliban is “legg’d like a man, and his fins like arms,” and Trinculo wishes he could take him to England as a freak-show commenting, “any strange beast there makes a man.” (Shakespeare, II, 2, 25-33). The Tempest is one of the earliest texts which expresses English colonialist discourses and attitudes to the New World. In it, Caliban, who represents the indigenous peoples of the New World, is ever on the edges of humanity, never wholly human or wholly animal. As the early nineteenth-century image above shows, he occupied this problematic space for centuries. Since the mid-twentieth century postcolonial approaches have seen him reconsidered and reconstructed in adaptations including Aimé Cesaire’s Une Tempête and Marina Warner’s Indigo. Such readings challenge the dehumanization of native peoples whose lands were subjected to Western colonisation. The gaze towards new lands and the future in The Tempest, however, is through the lens of the medieval past. Shakespeare’s Caliban was influenced by a long European tradition of ‘wild men,’ dating back through the Middle Ages to the fauns and satyrs of classical times. The wild man, or wodewose in Middle English, was a familiar figure in masquerades and masques, as well as the literature, of the medieval and early modern periods. Hayden White (1972) and Timothy Husband (1980) have both argued that the wild man operated as a contrast to civilised, socialised humanity; Caliban, who has known no humans save his mother until the arrival of Prospero and Miranda, and lacking the restraint imposed by society, is part of this tradition. His attempted rape of Miranda echoes violent sexual episodes associated with wodewoses in medieval texts such as the Middle English prose Alexander (see Yamamoto 156) and the Northern Homily Cycle. The lack of impulse control was associated with animal irrationality. Yet medieval wild men occupied a literal and metaphorical wilderness on the borders of humanity, sometimes human, sometimes animal, sometimes a monster (Young 48). The possession of a rational soul was the key to humanity according to medieval thought, which largely drew on St Augustine’s City of God for the topic. Yamamoto has pointed out that Mandeville’s Travels contains an episode where a wild man demonstrates he has a soul by showing knowledge of, and contrition for, sin (155), and a book of fables printed by William Caxton in 1483 contains a similar episode (Young 42-44). Sayers has argued that the English wodewose moved from beast to human over time, and that this increase in its humanity may have resulted from growing amounts of contact between Europeans and the peoples of Africa and the Americas. Such a timeline is oversimplified (Young), but Caliban is far more human than his predecessors either on stage or the page. He may have had to learn language from Prospero because his mother was mute, but he has a voice, and for all his rage and cursing he loves his home and speaks some of the most beautiful and haunting lines of the play in its praise (Shakespeare, III, 2 148-156). Constructed in The Tempest as part human and part animal, Caliban shares the liminal space occupied by medieval wodewoses, leaving his significance open to interpretation in later centuries. In the monstrously human figure of Caliban lie the seeds of a major figure of postcolonial resistance with his roots firmly in the medieval past. Dr. Helen Young is a postdoctoral fellow in the English Department at the University of Sydney. She currently holds an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award Cliff’s notes – historical and cultural context Historical and Cultural Context By the beginning of the seventeenth century, the threat of the Black Death (the plague) was diminishing, but it still continued to be a seasonal problem in London, which was overcrowded and suffered from poor sanitation and too much poverty. A hundred years earlier, Henry VII had formed alliances with neighboring countries and trade was flourishing in London. But the coming of trade changed the face of England. Instead of a country composed largely of an agrarian culture, England, and especially London, became an important center of trade. There was more wealth, and the newly rich could now afford to escape the congestion of the city. There was a need for large country estates, and so more and more farm land was enclosed. Displaced rural families fled to the larger cities, where crowding, unemployment, and disease increased with the increase in population. As city life flourished, there was a resulting nostalgia for the loss of country life. In response to this sentimentality, England's poets began to compose poetry recalling the tranquility of rustic life. Early in the seventeenth century, the masque that comprises much of the fourth act of The Tempest was becoming a regular form of court entertainment. Masques were elaborate spectacles, designed to appeal to the audience's senses and glorify the monarch. Furthermore, their sheer richness suggested the magnificence of the king's court; thus they served a political purpose as well as entertained. It is important to remember that the masque fulfilled another important function, the desire to recapture the past. As is the case with most masques, Prospero's masque is focused on pastoral motifs, with reapers and nymphs celebrating the fecundity of the land. The masques, with their pastoral themes, also responded to this yearning for a time now ended. The country life, with its abundance of harvests and peaceful existence, is an idealized world that ignores the realities of an agrarian life, with its many hardships. The harshness of winter and the loss of crops and animals are forgotten in the longing for the past. Elaborate scenery, music, and costumes were essential elements of earlier masques, but during the Jacobean period, the masque became more ornate and much more expensive to stage. Eventually the cost became so great — and the tax burden on the poor so significant — that the masques became an important contributing cause for the English Revolution, and ultimately, the execution of Charles I. Interpreting The Tempest Dr Sean McEvoy looks at the wide range of different ways in which Shakespeare has been interpreted over time, arguing that the interpretations reveal as much about the context of criticism as about the play itself. The Tempest (1611) is such a strange play that it has prompted many readers and critics to think that it must be an allegory. It tells of Prospero, the anxious magician whose devotion to his occult learning enabled his wicked brother Antonio to depose him from the Dukedom of Milan and exile him to a remote island. On the day on which the action takes place, Prospero seizes the chance to use his art to wreak vengeance when his enemies’ ship comes near. Prospero is accompanied in his exile, by his daughter Miranda, and he is attended by Ariel, a spirit of the air, and he rules over Caliban, described in the cast list as ‘a savage and deformed slave’. With its airy spirits, magic spells, apparitions and illusions The Tempest seemed in the past to stand out from the broadly ‘realistic’ human world of the histories, comedies and tragedies. What could Shakespeare be up to here? What message must be hiding beneath the surface? Different critical views have been proposed over the years, opening up the possible meanings of the play in fascinating ways, but also revealing as much about the critic and the context in which they interpret the play, as the text itself. Is it coded autobiography? In fact, The Tempest, like The Winter’s Tale and Cymbeline, was Shakespeare’s response to the new fashion for ‘romances’: tragicomedies with a fantastic or supernatural element. The plot of The Winter’s Tale turns on a divine oracle and its denouement requires a statue to come to life (apparently). In Cymbeline the Roman god Jupiter descends in thunder and lightning, sitting on an eagle. He throws a thunderbolt. Rather than look at the theatre for which Shakespeare was writing, 19th- and early 20th-century critics were wedded to a Romantic idea that the writer’s life had its fullest expression in his or her work, and read the plays as an account of Shakespeare’s own emotional experiences as his life progressed. The plays, in turn, were to be read as coded autobiography. (Incidentally, since William Shakespeare’s relatively undramatic middle-class life could not be mapped onto the high drama of his plays, this way of thinking led some to the weird conclusion that he couldn’t have written his own plays.) These critics looked in particular at two climactic moments: when Prospero causes the masque he has created to celebrate the engagement of Miranda to Ferdinand to disappear, and when he decides to renounce his magic and forgive his brother. In the first of these moments he declares: Our revels now are ended. These our actors, As I foretold you, were all spirits; and Are melted into air, into thin air; And like the baseless fabric of this vision, The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces, The solemn temples, the great globe itself, Yea all which it inherit, shall dissolve; And like this insubstantial pageant faded, Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff As dreams are made on, and our little life Is rounded with a sleep. This irresistibly seemed to be Shakespeare saying goodbye to the imaginary worlds his plays had created, with the clincher being his announcement that his theatre (‘the great globe itself’) was to disappear. When later he talks of how his ‘so potent art’ had summoned up storms and made the dead (historical figures?) walk again, and then announces that he will break his staff, it seemed clear to critics like John Dover Wilson, writing in 1932, that this must be Shakespeare’s own ‘farewell to the theatre’. If The Tempest had been Shakespeare’s last play this idea might perhaps be persuasive, if not very informative about the play itself. But it was known even in the 1930s that he went on to co-author three more plays after The Tempest. There is also some evidence that he went on to write The Winter’s Tale on his own after completing The Tempest. Critical opinion such as this can tell us as much about of the time of the critics and their ideological views as it can about the play. Prospero the Director Two particular interpretations of the play had wide currency in the late 20th century. When in 1956 the Berliner Ensemble brought Bertolt Brecht’s play Mother Courage to London it began a long-lasting fascination with the left-wing German playwright and theorist’s work which had a great influence both in the theatre and among critics. Brecht’s own plays don’t hide from the audience the fact that they are plays and seek to ‘alienate’ the audience from emotional connection to the action so that they can make judgements on the political situation depicted. In The Tempest, it could be argued, Prospero acts like a theatre director at many points. He instructs his actor Ariel how to perform down to the last detail the illusions which will terrify his shipwrecked brother and his ally Alonso, the King of Naples. These range from the initial tempest itself, to the magic table which is snatched away by Ariel as a harpy in Act 3 Scene 3, to the spell which traps them in a lime grove. Apart from the amazing masque which he puts on in Act 4 Scene 1 he also conjures up the hunting dogs which chase away the drunken conspirators Stephano, Trinculo and Caliban later in that scene. Prospero also makes his daughter and Alonso’s son Ferdinand fall in love as his ‘soul prompts it’. In this interpretation Prospero is not Shakespeare the playwright, but Shakespeare the Brechtian director. The Tempest is one big play-within-a-play, drawing attention to its own theatricality by exposing the way The Tempest itself manipulates our emotions and thoughts by showing just such a manipulation in action by Prospero. In the 1980s this approach coincided historically with an attack from some quarters on Shakespeare’s deployment in English culture as a means of making ‘natural … a ruling-class perspective and thereby … preserve the status quo’, as an essay of 1988 put it. In the same year the theatre company Cheek by Jowl toured Britain with a production of the play based closely on this interpretation of Prospero as director. Prospero was seen putting the other characters in costume and directing their moves on stage. We see the magician Prospero in action and we see how his tricks are done. Shakespeare himself shows us how he has duped us into believing in a set of patriarchal, monarchical views through his dramatic skills. Prospero the Colonist The other influential late 20th-century view took an interest in Caliban. It noted that one of Shakespeare’s sources for the play was an account of how an English ship taking the governor to the new American colony of Virginia had been thought lost in a storm, but in fact safely reached Bermuda. All on board were later discovered to be safe. This echoes what happens to Alonso’s ship, and Bermuda is even mentioned in play by Ariel. Since it also seems evident that Gonzalo’s account of his utopian society is taken from the French essayist Montaigne’s description of New World ‘cannibals’ – the word is so close to Caliban’s own name – it was argued that The Tempest was about the English colonisation of America, and about colonisation in general. The play becomes an examination of what happens when Europeans take over distant territories and enslave the inhabitants by force. The colonised seem to respond in two ways. Ariel seems to seek his master’s approval no matter how brutally he is threatened; but, though a spirit, his humanity is greater than his master’s and it is he who ultimately persuades Prospero that the rarer action is In virtue than in vengeance. The play becomes anti-colonialist: the coloniser is shown to have no innate moral superiority which justifies his imperialism. But more critical attention has been paid to Caliban, and to his statement to Prospero that: You taught me language, and my profit on’t Is I know how to curse. In a famous 1990 essay the American critic Stephen Greenblatt wrote of the ‘devastating justness’ of this remark. If Caliban is a savage, a would-be rapist of Miranda, he is also a product of violent enslavement by Prospero: no matter what the civilising discourse of the coloniser may be, his language is shot through with the selfishness, fear and hatred which underpin the colonialist project which Caliban learns through speaking his language. At the end Prospero admits this: this thing of darkness I Acknowledge mine And still Caliban himself, as Greenblatt points out, gets to speak perhaps the play’s most beautiful, lyrical and hopeful speech, which begins ‘Be not afeard. The isle is full of noises…’. The first notable example of many stage productions of The Tempest which made the play a commentary on imperialism was directed by Jonathan Miller in 1970, with two West Indian actors, Norman Beaton and Rudolph Walker, as Ariel and Caliban. The New World Tempest probably reflected the fact that Shakespeare criticism in the late 20th century was increasingly dominated by American academics. Its politics also suited well the strength of anti-imperialist feeling in the years following the American defeat in Vietnam and the growing multiculturalism of British urban society. But, as Jerry Brotton pointed out in 1998, the New World Tempest clearly gets its geography wrong. Alonso’s ship is on its way from Tunis to Naples. Prospero’s island, if anywhere, must be somewhere in the Mediterranean. An English Caliban? Caliban’s language also turns out to be much more European, too. Some new research published in 2013 by the American academic Todd Andrew Borlik has gone back to looking at the very English landscape of Caliban’s world. When Caliban curses Prospero, he twice calls for diseases to rise from the fenlands and to infect his master. Antonio also sees the island as a stinking ‘fen’ and Caliban says it has ‘brine pits’. Caliban’s tasks seem to be those of fen-dwellers, collecting wood and catching fish. The fens are a large low-lying area in eastern England. In the early 17th century they were marshy and wild, but there were many schemes to drain them and exploit the fertile farm land that would be produced (as parodied in Ben Jonson’s 1616 comedy The Devil is an Ass). London was full of money-making schemes aimed at taming the fenlands. The inhabitants of this muddy and reedy wasteland were regarded as little better than savages, as superstitious near-pagans who believed in monsters and spirits who dwelt there. Borlik suggests that the legend of St Guthlac was well-known in Shakespeare’s time. Guthlac was an 8th-century scholarly hermit who retired to the Lincolnshire fens. Guthlac could make the air and water obey his commands; he brought demons under his control. He has an angelic familiar, like Ariel, and a magic garment, like Prospero’s cloak. In other words, we need not look any further than provincial England for the isolated wilderness and the reclusive magician. This is not a postcolonial interpretation, it turns out, but an environmentalist one. Caliban is the wild spirit of the fens and also its inhabitant trying to resist the scientific (i.e. magical) exploitation of the wilderness – the ‘colonisation of non-human nature by anthropocentric science’, as Borlik puts it. It’s an interpretation for our time. Caliban’s curses call on the forces of nature to fall on their enemies in a kind of ‘environmentalblowback’, when nature enacts its revenge on its exploiters. The Tempest isn’t a mystery; but it is a richly open text that anticipates the world created by the actions of our early-modern forebears who wielded power. Dr Sean McEvoy teaches English at Varndean College in Brighton. He is the author of William Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’: a Sourcebook. This article first appeared in emagazine 65, September 2014. Prospero – A Renaissance Magus Malcolm Hebron introduces some specialist contextual information about Renaissance attitudes towards magic, learning and politics and considers the way in which this knowledge illuminates The Tempest. The Tempest has many familiar characters: the scheming usurper, the clown, the virtuous young nobleman, the faithful old courtier. We can recognise these types in other Shakespeare plays, and indeed in dramas today. But what of the figure at the centre of the play, Prospero himself? We can place him as a kind of wizard, a Gandalf or Dumbledore perhaps, but to a contemporary audience he would have been identifiable at once as something slightly different – a Magus, or mage, an ancestor of the gentle headmaster of Hogwarts, but not sharing all of his traits. Understanding what a Magus was can help us to answer one of the most intriguing questions raised by this play: is Prospero’s magic a force for good, or something more sinister? The Renaissance Mage In Renaissance culture a Magus is someone who understands the cosmos and man’s place within it. This knowledge is gained principally through study. Prospero prizes his books above his dukedom, and we can easily guess what kind of books they are. They would include Astrology, the study of planetary influences on the earth (Prospero notes his magical career is at its height or zenith while a particular star is in the ascendant). Prospero might have had to hand the mystical texts ascribed to the ancient Egyptian sage ‘Hermes Trismegistus’, which discuss how, through self-knowledge, a person can ascend to the divine. Perhaps, like the Italian scholar Pico della Mirandola, he also studied the Cabbala, the secret Hebrew Law given to Moses, where deeper meanings are encrypted within the letters of the text. A self-respecting Renaissance mage would also have been familiar with the writings of the philosophical school known as Neoplatonism, based on the idea that the soul naturally yearns to leave the body and be with God. Then there was Alchemy, concerned with the transmutation of matter (interestingly, in Alchemy, a ‘tempest’ is the term for sifting out impurities from a mixture). Such studies were ‘hermetic’, closed off to all but the initiated. Next to these, Prospero would also have pursued studies we would deem more scientific, since a Magus must also understand earthly phenomena through careful observation. The goal of all this study is to transcend human limitations and achieve a complete understanding of the universe: the Magus is familiar with celestial, inanimate forces and sees how, through a complex system of ‘sympathies’ and ‘correspondences’, these are reflected on earth and in the soul of man. At the highest level, the Magus has the wisdom to perceive the mind of God. To attain this wisdom, he must not only study but also pursue a pure life, untainted by sin. A Force for Good? A Magus is, then, someone who devotes himself to the pursuit of wisdom. There were Renaissance scholars who pursued just such a course of study, anxious to unite the various strands of learning – classical, Jewish, Christian – in a quest to pursue a transcendent understanding of the universe. They included scholars like Pico, Marsilio Ficino, Cornelius Agrippa and the Englishman John Dee (a likely source for both Prospero and Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist). But a Magus is not merely a contemplative figure. His wisdom gives him the power to act, and it is this power that makes him controversial. The virtuous Magus acts only in accordance with divine Providence: he assists in God’s work, and is thus a force for good. For example, he might apply his knowledge of the natural powers of plants to heal (several magi were medical doctors); or he might use astrological knowledge to calculate the ideal times for a harvest. John Dee was consulted on the most auspicious date for Elizabeth I’s coronation. ‘Good’ magic of this kind is magia, or theurgy. It does not interfere with God’s actions, but works with them, to the greater good of humankind. A Force of Evil? The powers of a Magus might equally lead him into bad magic, or goetia. The Church was particularly suspicious of those parts of hermetic study that seemed to suggest humans could alter nature as God has ordered it. Hermes Trismegistus, for example, gives instructions for calling down spirits to animate statues, a dangerous interference with the cosmos. Then there were the more usual kinds of manipulation, involving using this specialist knowledge for personal gain, for example by getting money from people by scaring them or providing a suitably flattering prophecy. There was also the possibility of dabbling in the Occult, or black arts. The Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno, was burned at the stake in 1600 on charges of dealing with the Occult. Reformed Protestant England was generally suspicious of magic for its associations with Catholic practices and teachings (such as the idea that relics held miraculous powers), and King James I was highly suspicious of magical activities. Dee was forced to defend himself and prove that his practices were in harmony with the divine, and though he succeeded, he died poor and disgraced in 1608, just two years before The Tempest was (probably) written. Weighing Up Prospero’s Intent The Magus, then, was a controversial figure, and it is not surprising that Prospero and his actions have stimulated much critical debate. Is he a virtuous mage, practising magia for a beneficent end? Or does the magic of The Tempest have a darker side? Let us review briefly the case for each. Several scholars have argued that Prospero is a Magus using his powers for the greater good, not for personal gain. His theurgy contrasts with the destructive goetia of Sycorax. If he simply wanted personal vengeance, he could have killed everybody in the storm. But he makes sure that no one is harmed. His aim is to bring his enemies to recognise their evil actions and repent, thus restoring them to divine grace. The illusions he creates are all for this purpose. Prospero also wishes to marry his daughter to a worthy suitor. From the pure chastity of this couple a truly noble generation should emerge, ensuring the security of the dukedom. Ariel represents Prospero’s art in its most spiritual form, free from the constraints of the body. Caliban symbolises his earthly side, and the fact that Prospero clearly has control over Caliban shows he has the proper discipline over his lower human tendencies. When Prospero renounces his magic art, it is not a sign of guilt, but a necessary step to resuming his worldly duties as a Duke. The final scene of pardon and compassion is a fitting climax for this beneficent magic. If the reconciliation is not complete, it is because Antonio is still unable to repent: not even a Magus can take away divinely bestowed free will, or rid the soul of evil. However, Prospero and his magic have also led to different readings. Some critics argue that his absorption in study is irresponsible, taking him away from his duties as Duke and allowing his brother to take over. At many points in the play, Prospero becomes angry, and his treatment of Ferdinand is hard to understand. His irritable demeanour and violent imagery hardly suggest a serene mage high above the world of human rivalry. Prospero himself seems to doubt his own ‘rough magic’ and its dubious effects: Graves at my command Have waked their sleepers. It is as if he has been playing God, and wants to step back from this interference with the natural order. (This speech has also been interpreted as Prospero moving from a crude stage of magic to a more refined one.) Even the contrast with Sycorax is not wholly clear, since we have no other real source about her besides Prospero himself. At one point, it is Ariel who apparently points Prospero away from anger to higher thoughts of compassion, based on a human sympathy he is in danger of losing. Immersed in the ideal world of his books, Prospero is possessed by a desire for impossible purity in the world, and incapable of seeing that evil is a normal part of human affairs: he was naive about his brother, and foolish to leave Caliban alone with Miranda. He still seems to find it hard to believe that Caliban and his associates would want to plot against him. According to this argument, Prospero undergoes a journey of self-knowledge in the play: his magic has distanced him from real human behaviour, and he has to renounce it to return from a world of illusion and manipulation – a world similar to the art of theatre – to the human community. A Drama, Not a Thesis Which of these arguments seems stronger? The magic in the play does seem to be directed towards the good end of repentance and reconciliation. Yet the play is a drama, not a thesis for or against magic, and it surely reflects some of the suspicious atmosphere of the time. Prospero is not a benign sage but a troubled soul, given to irascible outbursts and brooding soliloquies. He does indeed seem ill at ease with his art and its ‘vanity’. Ariel, the disembodied spirit, has to be released; the world must be returned to. Perhaps the play is not attacking magic but suggesting that it tests our humanity to the utmost. As Prospero leaves the island, he leaves us with a host of difficult questions, about magic, about colonialism, and about how successful the outcome of the play really is. On page and stage, the magical action of The Tempest is an abiding riddle, one to which no answer seems altogether satisfactory. Perhaps this is fitting since magic is ultimately beyond rational understanding, a hermetic world, a mystery. Malcolm Hebron teaches English at Winchester School. This article first appeared in emagazine 51, February 2011. Caliban's last sigh Auden's reworking of The Tempest is irritatingly didactic, but 60 years on, the imaginary worlds of The Sea and the Mirror are as solidly mysterious as ever, says Jeremy Noel Tod Saturday 27 September 2003 01.21 BST – The Guardian The Sea and the Mirror by WH Auden, edited by Arthur Kirsch Although it is now standard practice in academic publishing, it seems odd that "advance praise" blurb should have been provided for a reprint of a poem that first appeared in the 1940s. Odder still that the dust jacket should then quote, from Sylvia Plath's Journals , a description not of the poem but the poet: "Auden...the naughty mischievous boy genius...gesticulating with a white new cigarette in his hands, holding matches, talking in a gravelly incisive tone about...art and life, the mirror and the sea. God, god, the stature of the man." The publishers of this critical edition presumably sense that Auden's stature is not what it was; Plath, though, should attract the attention of a large contemporary readership. It is also an expertly revealing sketch: Auden the compulsive lecturer; the chain-smoking, roving don. When Auden went off to America in 1939 his poetry, it is generally agreed, went off too. Philip Larkin's diagnosis, in 1960, seems accurate: by emigrating, Auden lost "his key subject and emotion - Europe and the fear of war - and abandoned his audience together with their common dialect and concerns". Instead, wrote Larkin disapprovingly, "he took a header into literature". The first long poem to result, New Year Letter (1941), was a dud. Composed in sometimes heroically awful couplets - "The very morning that the war / Took action on the Polish floor" - it came with even longer "Notes", quoting chunks from the poem's implied reading list. Far from the action, Auden lectured his readers. The Sea and the Mirror (1944) - a long poem billed as a "commentary" on Shakespeare's The Tempest - retreated even further into the library. The result, however, was some of his most inventive and moving later poetry. Shakespeare's strange final play presents a usurped magician, Prospero, who brings his enemies to their knees on an enchanted island, and then renounces his powers. It contains echoes of virtually every other Shakespearean work, and is a honey-trap for the critic seeking a neat allegorical map of Shakespeare's mind. Auden, with his love of explanation by system and schema (Freud, Marx), was such a critic. In 1944, he was orienting his ideas by Christian philosophy. This edition reprints a huge chart of universal "antitheses" which he drew up while writing The Sea and the Mirror . It divides everything from "Physical Diseases" to "Political Slogans" along theologically dualistic lines (two flavours of Hell either side of existential vanilla). Auden found such dualistic oppositions everywhere in The Tempest : the otherworldly Prospero and his Machiavellian brother, Antonio; ethereal Ariel and earthy Caliban. Shakespeare only hints at what Auden rigidly schematised. Arthur Kirsch, commenting on Auden, doesn't seem always to realise this. For example, Kirsch's introduction states that Ariel and Caliban (Prospero's non-human servants in The Tempest ) "cannot exist without each other". This idea is not substantiated by a single line in the play. It does, however, explain Auden's beautiful closing lyric, "Postscript (Ariel to Caliban. Echo by the Prompter)": Never hope to say farewell, For our lethargy is such Heaven's kindness cannot touch Nor earth's frankly brutal drum; This was long ago decided, Both of us know why, Can, alas, foretell, When our falsehoods are divided, What we shall become, One evaporating sigh ...I In other words (Auden's to Plath), Ariel, the "creative imaginative" spirit, is nothing without Caliban, "the natural bestial projection". Auden wanted to correct what he saw as Shakespeare's Manichaeism in The Tempest : that is, blaming the bestial for the imperfections of the spirit. In the theology of The Sea and the Mirror , man is equally imperfect in mind and body (the "falsehoods" of Ariel and Caliban). Consequently, he will be existentially anxious until death - when, the echorhyme fadingly suggests, the evaporating "I" will finally know wholeness. This delicate technical conceit is typical also of the lyrics given to Shakespeare's characters in the book's middle section. Each is a discrete poem, particular in form and diction. Inevitably, they are not all equally successful - inconsistency is the price of predetermined schematic construction. Loveliest is "Miranda", Prospero's daughter, who speaks a villanelle of innocent adoration for her new husband, Prince Ferdinand - affirming, repeatedly, My Dear One is mine as mirrors are lonely, And the high green hill sits always by the sea. The real achievement of the poem, though, is in the two sections that enclose this lucky dip of lyric skill. The first is "Prospero to Ariel": a measured, unrhymed, touching speech of farewell, in which Prospero prepares to return to unmagical mortality and general disillusionment. Auden takes Shakespeare's sad little touch at the end of The Tempest - Miranda: "O brave new world / That has such people in't!" Prospero: "Tis new to thee." - and wittily expands it. "Will Ferdinand be as fond of a Miranda / Familiar as a stocking?" Prospero wonders, imagining himself "an old man" Just like other old men, with eyes that water Easily in the wind, and a head that nods in the sunshine, Forgetful, maladroit, a little grubby... (Kirsch's notes make public for the first time an amusing line that Auden - part-time mischievous boy genius well into old age - excised from the final draft: Prospero on adolescent masturbation, "the magical rites of spring in the locked bathroom".) The second set-piece in The Sea and the Mirror is "Caliban to the Audience". This prose monologue breaks with the versified fictions of character and narrative to address the modern reader directly. Auden's Tempest characteristically leaves out Caliban's tactile nature poetry. Instead, the subservient savage is given the elaborate prose style of late Henry James, and is employed to evoke the topography of another enchanted isle, the musty, pagan-industrialised, storybook England which the young Auden (who once played Caliban in a school production) made his own: "Carry me back, Master, to the cathedral town where the canons run through the water meadows with butterfly nets...an old horse tramway winds away westward through suave foothills crowned with stone circles...to the north, beyond a forest inhabited by charcoal burners, one can see the Devil's Bedposts quite distinctly, to the east the museum where for sixpence one can touch the ivory chessmen." The Sea and the Mirror succeeds because, despite its simplistic schematising, its imaginary worlds are solidly mysterious; only Auden could have dreamed them. Caliban's speech is particularly rich with brilliantly casual specifics ("sunset glittered on the plate-glass windows of the Marine Biological Station"). The wonderful writing remains subservient to a didactic end, however. This, it transpires, is a campy hellfire sermon. We are intended ultimately to gag on the over-egged nostalgia; as WH Caliban goes on to explain, we will never be carried back to Paradise in this life. So, the poem is more than a "commentary" on Shakespeare; it is a lecture that deduces from its text an existential moral never stated therein. The Tempest , in fact, is a marvel of ambiguity about cosmological questions (count the number of different gods invoked in it). Auden recast the dramatic as the didactic. This luxuriously produced edition's exhaustive critical apparatus - which includes extracts from Auden's private explanations of his project, as well as from his criticism and working notes - makes the difference unexcitingly clear. New readers should go straight to the poem. · Jeremy Noel Tod teaches English literature at the universities of Oxford and East Anglia.