1 The Crisis of Republican Government and the Calling of the

advertisement

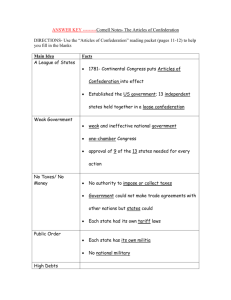

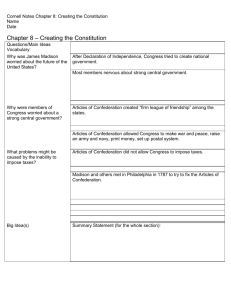

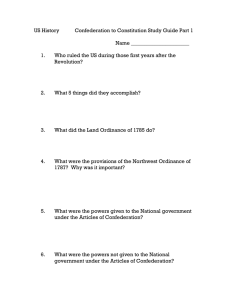

THE ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION, THE CRISIS OF REPUBLICAN GOVERNMENT, AND THE CALLING OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION Contact Information Alan Gibson, CSU, Chico, 400 W. 1st St., Chico, CA 95929-0455 530-898-4952 Agibson@csuchico.edu Thesis of the First Two Presentations Both the terms of the settlement of British North America and Americans’ experiences during the American Revolution understandably led them to favor highly decentralized and democratic (for that time) political systems following the Revolution. Reacting against an effort to impose centralization by a monarchical power, the Americans formed a decentralized, republican polity or a truly federal union. Experience with this “Confederation System” under the Articles of Confederation, however, proved that it led to its own sets of problems, including the impotence of the national government, problems within the states, and even the possibility of disunion and war between the states. The Framers of the Constitution, then, created a different kind of federal union to respond to these problems. Colonial and Revolutionary Origins of the Confederation System Settlement of North America The American colonies were settled without a great deal of supervision by the British government or the chartered trading companies that created them. Neither the British government nor these companies had the resources to finance or control the process of colonization in North America. The reach of the Atlantic was too great. In theory, American colonists were beholden to the King and the British crown exercised absolute authority over them. In practice, the British empire was a highly decentralized federal union from the beginning with the colonies as selfgoverning entities. Origins of the American Revolution After 1763, Parliament and the crown enacted a series of mercantilist measures and sought to rationalize the administration of the colonies (to provide uniform rules for their conduct. They also sought to defend the colonies (by placing British regulars on the North American continent). Most infamously, the crown sought to raise revenue for this defense of the colonies. Eventually, the crown asserted authority independent of colonial consent. Colonial Expectations and Revolt The colonists had engaged in self-rule for at least a century and believed themselves to be Englishmen equal to anyone in the mother country. Thus, British policies from 1763 to 1776 challenged their expectations of local control, violated their understanding of the rights of Englishmen, and insulted their understanding of their place within the British empire colonists. Denying the need for colonial representation led the colonists to feel like they were little better than the Native Americans that they sought to “pacify” or the Africans that they had enslaved. Federal Union with Britain Few of the men who would eventually become leading revolutionaries initially wanted to separate with the mother country. The belief that revolution and separation were necessary was a long and tortured path. As the imperial crisis worsened, the men who would become revolutionaries (Adams, Jefferson, James Wilson) wanted a federal union with the mother country. Eventually, they came to want to be a part of a federal union in which they recognized a common King with British citizens in Britain, but governed themselves in their local colonial assemblies. They wanted, in other words, for local assemblies to set their own trade and tax policies and thus to be sovereign in North America, but colonists also still wanted to be a part of the British Empire under the King. Federal Union Among the American States Such a relationship was of course unacceptable to the Crown and Parliament. The more the Crown tightened its grip, the more British colonists in North America came to believe that revolution and separation were the only possible alternatives. Hence, they declared independence. But most important, what did they do upon independence? They formed a federal union among themselves similar to the one that they had sought with the mother country. The states were joined in loosejointed confederation under the Articles of Confederation. The Articles of Confederation The Articles as a “Firm League of Friendship” A Confederation on the ancient model of confederations. Delegates to the Continental and Confederation Congresses were ambassadors. They were the states’ men, not statesmen. Equality between the states. Each state cast one vote in Congress. Extraordinary majorities were required to pass legislation on treaties, wars, and economic matters. The Articles conferred limited powers for limited purposes. Explicit powers include the power to coin and borrow money, requisition the states for men and money, wage war, conduct diplomacy, negotiate treaties, establish uniform standards of weights and measures, regulate Indian affairs, decide disputes between the states, and admit new states into the nation. Article II: “Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.” What was Accomplished Under the Articles of Confederation Government 1. Coordination of the War Effort and Effective Negotiation of the Treaty of Paris 2. Peace Among the States was Maintained 3. Emancipation of slaves and abolishment of slavery in Northern States. 4. Development of participatory democracy within the states 5. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 was passed. Orderly settlement of the West was begun. Problems With the Articles “The Poor Federal government is sick almost unto death.” Henry Knox, quoted in Cathy D. Matson, and Peter S. Onuf, A Union of Interests: Political and Economic Thought in American America (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1990), 54. Powers Not Conferred by the Articles Powers Not Conferred by the Articles of Confederation The Articles provided no power to compel taxation. Instead, quotas of payment were requested from the states. Under the Articles, requisitions were in theory mandatory. Congress set forth a dollar value for each state. States then raised the money through whatever taxation system that they had in place. There was, however, no system to make the states comply. Many delegates to Congress argued that coercion was an implicit power of the articles, but coercion was impossible against the largest states and impractical and destructive against any of them. Powers Not Conferred by the Articles of Confederation The absence of a means of making the states comply with orders for requisitions created a free-rider problems. The “goods” or benefits delivered by the national government were available to states whether they complied with requests for requisitions or not. Powers Not Conferred by the Articles of Confederation The Articles conferred no power on the government to establish uniform commercial regulations. No powers under the Articles were exercised directly upon individuals. Was a government really created by the Articles of Confederation? “Short Leash” Republicanism and the Articles of Confederation The government created by the Articles had only one branch (Congress) and thus no independent judiciary, executive, or scheme of separation of powers. The Articles stipulated that each state could have between 2 and 7 delegates. Delegates were appointed annually in “such a manner as the legislatures of each State shall direct.” Delegates could be recalled at any time by the state legislatures and were subject to rotation in office (no delegate could serve for more than three years in any term of six years). The constituency of the delegates was their respective state legislatures, not the people. The state legislatures paid the salaries and expenses of the delegates. “Short Leash” Republicanism and the Articles (continued) A President was chosen by Congress to serve as a presiding officer over the Committee of the States (a committee that was formed to do the business of Congress when it was not in full session). The President was also subject to rotation as each was eligible to serve only one year in every three. “Short Leash” Republicanism and the Articles (continued) Article IX courts were created to consider land claims. No congressional delegate could serve on these bodies and the judges were chosen in a complex process to ensure their impartiality. The republican character of the Articles was insured by the prohibitions in Article VI against the granting of titles of nobility by the states or the national government or their acceptance by any person who held office under the United States. Freedom of speech and debate were guaranteed in Congress, members could not be questioned outside of Congress for speeches made inside it, and were protected coming and going to Congress. A journal of the proceedings was published and the votes of each delegate would be recorded on the request of any delegate. The Articles thus attempted to meet the criteria that we call transparency and publicity. The Second Tier in the Confederation System: The First State Constitutions, 1776 1787 “Short Leash” Republicanism is even more evident in the state constitutions. Annual Elections of the Lower House (12 of 14 state constitutions adopted between 1776 and 1787) and Governors (10 of 14 state constitutions) Short Terms for Members of the Upper House (no state had a longer term than 5 years and four states had annual elections). “Good Behavior” for Judges Directly elected branches. The lower House was directly elected in each state, the upper House in Eight States, and Governors were elected by the legislature in a majority of states. Judges were appointed by the legislature or jointly between the legislature and the Governor. The Second Tier in the Confederation System (continued) Additional institutional features and plebiscitary devices in the states included: rotation in office, written guarantees for the right of the people to instruct their representatives into their state Declarations of Rights, schemes of separation of powers designed to control the Executive. Numerous representatives elected from small electoral districts and, perhaps most importantly, were confined within a small geographic compass compared to the vast extended republic governed by the national government created in 1787. The Crisis of Republican Government Powers Not Conferred by the Articles of Confederation The inability of the government under the Articles to secure money to have a functioning budget meant that the United States was really not able to pay for the debts that it incurred. Instead, paper money was printed which became worthless. The government gave this money in payment for supplies that were impressed (stolen) from ordinary Americans. This created great resentment. Loans were secured from other countries. But would they be repaid after the Revolution was completed? In 1786, Congress attempted to float a loan for $500,000 but attracted not a single subscriber. (Calvin Johnson, Righteous Anger, 29) Widespread Non-compliance States refused to comply with Congressional Requisitions. From 1781 to 1786, Congress requested 15 million dollars from the states but received only 2.5 million. As Jack Rakove has noted the Americans fought a Revolution based in large part on the grievance of “No taxation without representation,” but ended up with a system of representation without taxation. Widespread Non-compliance “On average states paid 53 percent of the quotas payable in specie and 27 percent of the quotas payable in indents.” [Indents were simply certificates issued at the close of the American Revolution for interest due on the public debt.] Georgia paid nothing under the period under the Articles. (Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, Volume 1, Note 6, p. 221) “The Newburgh Conspiracy” The inability of the government to finance the Revolution and pay the debts of the United States had profound effects. In March, 1783, the Continental Army threatened revolt. They had not been paid for several months. They were tired, poorly clothed, and hungry. Congress seemed obtuse to their needs. They had been promised a generous pension for their service in the war, but this seemed unlikely now. Hamilton seems even to have been behind the revolt. “The Newburgh Conspiracy” Washington would have none of this. He addressed his officers and assured them that he would do everything in his power to get them the benefits that they had been promised. But he would not led or abide a revolt. His commitment was to the rule of law. He was a military leader under civilian control. “The Newburgh Conspiracy” Most famously, after reading a speech that he had written, Washington pulled a letter from his pocket from a Virginia delegate to the Confederation Congress, Joseph Jones. Jones had written Washington expressing sympathy for the cause of the troops and pledged to work in Congress on their behalf. Washington, however, initially had trouble reading the letter and famously observed, “Gentlemen, you must pardon me. I have grown grey in your service, and now I find myself going blind. Washington’s officers dispensed in tears. Governmental Organization and the “Vices of the Political System of the United States” The organization of government established under the Articles of Confederation also led to numerous other “vices of the political system of the United States” – to borrow Madison’s phrase. Most importantly, the absence of the power to regulate commerce and to compel taxation led to commercial warfare between the states and to inadequate revenues for the national government. Encroachments of the States on the Rights of Each Other States restricted access to each other’s ports and passed laws favoring their vessels. They also restricted commercial intercourse with each other. This brought on retaliatory measures by other states. “Commercial Warfare” between the states was common. Encroachments Upon and Violations of Federal Authority States encroached on Federal Authority – States conduct their own wars with Indian nations and negotiate their own treaties. The most important of these were Georgia’s famous war with the Creek Indians. States violated treaties negotiated with the United States – E.g. the Paris Peace Treaty of 1783. Many Framers feared that this would lead to war with other nations. A Crisis of Union Many of the Framers worried that the corporate aggressiveness of the states – both against federal prerogatives and against each other - would lead to the civil war and the creation of separate confederacies. Would the union survive under the Articles of Confederation? Vulnerability of the United States to foreign powers Britain and Spain still occupied lands on North America. France, Britain, and Spain all still had territorial ambitions in North America. The American army following the Revolution was not wellorganized or prepared. Indeed, it could barely be said to exist. The National Debt and State Debts By 1779, the United States had emitted at least $226,200,000 in paper bills. The state governments had emitted about 209,000,000. The United States was some 435 million dollars in debt after the Revolution. This was an extremely large amount in the context of these times. How was this to be paid? Multiplicity, Mutability, and Injustices of the laws of the states. Pressured by majorities within the states, state legislatures passed paper money legislation, stay laws, and other debtor relief legislation. Many of the men who would later become Founders believed that this was a fundamental violation of the rights of contract and property. Such legislation, Madison argued, brought into question the fundamental principle of republican governments, that the majority is the safest guardian of the public good and private rights. Multiplicity, Mutability, and Injustices of the laws of the states (continued) “The mutability of the laws of the States is found to be a serious evil. The injustice of them has been so frequent and so flagrant as to alarm the most ste[a]dfast friends of Republicanism. I am persuaded I do not err in saying that the evils issuing from these sources contributed more to that uneasiness which produced the Convention, and prepared the public mind for a general reform, than those which accrued to our national character and interest from the inadequacy of the Confederation to its immediate objects.” Madison to Jefferson, Oct. 24th, 1787 Other Problems with the Confederation Government The Articles were never popularly ratified. They thus lacked legitimacy. The Articles proved impossible to amend. All 13 states had to approve amendments. Rhode Island was unwilling to comply with amendments granting the national government the power to levy an impost or to regulate commerce. Navigation Rights on the Mississippi Many of the Southern men who would eventually fight for a new constitution believed that navigation rights on the Mississippi River had to be secured to insure the value and settlement of western lands and he ability of American farmers to make their agricultural products available for export. In 1784, Spain closed the Mississippi to American trade. Within two years, John Jay – then Secretary of State under the Confederation – presented to Congress a treaty that proposed ceding to Spain navigation rights on the Mississippi for 25 years. New Englanders favored this treaty because it promised to increase commerce between Spain and the fledgling United States. This heightened sectional conflict. Shays’ Rebellion Massachusetts imposed a 60 % tax increase to dissolve its revolutionary war debts in three years. Daniel Shays, a revolutionary war veteran, then led a revolt to prevent foreclosures on the farms for several thousand (estimates range from a few hundred to 15,000) “desperate debtors” in Massachusetts. Shays’ rebels shut down the court system in western Massachusetts and threatened a government arsenal in Springfield, Massachusetts. Henry Knox, one of Washington’s generals during the Revolutionary War, was employed by the Confederation Congress to estimate the number of men in rebellion and whether action should be taken. He probably exaggerated the number of rebels and certainly exaggerated their threat, but his reports were circulated among the nation’s elite. Shays’ Rebellion The rebellion was put down by a voluntary force raised by Massachusetts governor James Bowdoin. Four rebels were killed by the 4400 troops raised and under the command of General Benjamin Lincoln. Daniel Shays escaped and lived to be 84 in the state of New York. Shays’ Rebellion Shays’ Rebellion was important for several reasons Illustrated the Impotence of the National Government and the problems within the States. The Confederation Congress could not put down the rebellion quickly because it required compliance by all the states to raise a national army. Furthermore, the Congress had no money to pay any troops who acted. Shays’ illustrated foreign influence in America as many Americans thought the British had instigated the rebellion. Shays’ Rebellion Most important, Shays’ Rebellion created a sense of panic and impending doom among the nation’s elite. Incidents or threats of violence also took place in Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Maryland, South Carolina, and Virginia. “There are combustibles in every State, which a spark might set fire to.” Washington to Henry Knox, 26 December 1786, Fitzpatrick, XXIX, 122 The British had predicted the United States would not long exist. Many European nations had believed likewise. This event seemed to verify these predictions. Shays’ Rebellion Among the nation’s elite, this also illustrated the natural tendency of republics. They were said to be turbulent, shortlived, and violent in death. Shays’ rebellion seemed to confirm this prediction as well. As much as any event, Shays’ rebellion galvanized the nation’s elite into believing that a stronger national government was necessary. Shays’ rebellion in particular led reformers to fuse a series of previously discrete weaknesses into a diagnosis of pathology. The Critical Period in American History? Progressive Historians have argued that there was general prosperity in the United States in the period from the end of the Revolution to the calling of the Constitutional Convention. The portrait of impending doom that is usually given of these years, they argue, is a fabrication by the Federalists who fear the loss of property and power by the rising tide of democracy in the United States. The Critical Period in American History? Most recent scholarship has suggested that the critical period was indeed critical. Even if popular rebellions did not pose that great a threat and Washington was able to prevent calls for a military coup, the Federalists were rightly concerned about with the splintering of the union, civil war between the states, and foreign influence on American soil. Washington as King?, Three Separate Confederations?, or a New National Government? On the eve of the Convention, some people wanted to reestablish a monarchy with Washington as King, others wanted to create three separate confederacies, and still others wanted to strengthen the national government. Few anticipated the bold move that would come at the Convention. The Annapolis Convention (1786) A trade convention was called in 1786 at the request of Virginia Assembly. Madison had persuaded the Virginia assembly to call this convention. This convention was called to "consider how far a uniform system in their commercial intercourse and regulations might be necessary to their common interest and permanent harmony." (Annapolis Convention Resolution) The Annapolis convention was attended by 12 delegates from five states: New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, New York, and Virginia. See Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, I, 176-179 for the lead up to the calling of the Constitutional Convention. Annapolis Convention (continued) The meeting was important because before adjourning, Alexander Hamilton suggested that a second convention be held to reform the Articles of Confederation. The delegates then adopted a resolution suggesting that the second convention have “enlarged powers” to address additional problems encountered with the Articles and that it should “devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union.” (Annapolis Resolution) Congressional Authorization for the Convention “That it be recommended to the States composing the Union that a convention of representatives from the said States respectively be held at on for the purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation and perpetual Union between the United States of America and reporting to the United States in Congress assembled and to the States respectively such alterations and amendments of the said Articles of Confederation as the representatives met in such convention shall judge proper and necessary to render them adequate to the preservation and support of the Union.” Congressional Authorization (continued) The most famous exposition of this resolution came in The Federalist No. 40 where James Madison argued that the Annapolis resolution and the Congressional resolution justified abandoning the Articles of Confederation altogether and creating a new constitution. Together, Madison suggested, the resolutions called for the creation of a national government that rendered the Articles "adequate to the preservation and support of the union." To be sure, Madison added, they also suggested that this was to be done by revising the Articles of Confederation. But, Madison queried, what were the delegates to do when they found out that it was impossible to meet the goal of preserving the union merely by amending or reforming the Articles? The proper rule of construction, Madison argued, was to suggest that the end or goal (preserving the union) was more important than the means of revising the Articles. These two expressions defining the authority of the Convention, Madison argued, were irreconcilably at variance with one another and the more important of the two was the end of preserving the union. If we had to choose between the happiness of the American people and the preservation of the Articles of Confederation, the happiness of the American people was clearly more important. Eventually, Madison evoked the language of the Declaration of Independence - that it is the right of the people to "abolish or alter their governments as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness." - to shore up his case that it was legitimate to abandon the Articles. Madison rested his case on the shear necessity of a new constitution, not on the any explicit authorization from the Annapolis Convention (which was itself extra-legal) or Congress. Washington’s Agrees to go to Philadelphia After being wooed by James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, George Washington agreed to serve on the Virginia delegation to the Philadelphia Convention. Washington’s prestige lent legitimacy to the gathering. The Constitutional Convention A coup d'état? The Philadelphia gathering of 1787 was certainly an extra legal convention and perhaps an illegal one. In the Philadelphia Papers, the delegates were known as the “conspirators” and Independence Hall was called “the dark conclave.” The delegates got over their lack of legal precedent by arguing they could propose anything, but only the people could ratify the product of their labors. The men of Philadelphia Fifty-five men attended the Convention. They were an elite unified by wealth, education (mostly lawyers), and geographic region (most were from the coastal regions and cities). There was no true radical at the Convention, no Thomas Paine or Daniel Shays. “An Assembly of Demi-Gods?” The meeting included George Washington who had been courted to attend the Convention by James Madison. Washington served with characteristic gravitas as the President of the Convention. The meeting also included an elderly Benjamin Franklin. The most important and active delegates were James Madison and James Wilson. Most scholars believe that the Constitution embodies their vision of the role of the national government. Note who was not at the Convention: Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, John Jay, Thomas Paine, and John Hancock. On a Less Lofty Note “The physical conditions – an average of close to forty men, most of them obese, crowded into a modest sized and not well ventilated room for five to seven hours a day during an intensely hot and muggy summer – ensured that those compromises would not always be accepted with good grace.” Forrest McDonald, Novus Ordo Seclorum, 225. What Happens at Independence Hall Stays at Independence Hall Delegates choose to close the doors. The dark closet and the conspirators. Story of Washington finding someone’s notes. Voting by States with Each State Getting One Vote This virtually insures that equal representation of the states will take place one branch Independence Hall James Madison On Madison “Every person seems to acknowledge his greatness. He blends together the profound politician with the scholar. In the management of every great question he evidently took the lead in the convention .... He always comes forward the best informed man on any point in debate. The affairs of the United States he perhaps has the most correct knowledge of any man in the Union.” – William Pierce, Georgia Delegate to the Convention, Max Farrand ed., The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1937, 4 vols.) 3:94. Another Description of Madison “He derives from nature an excellent understanding...but I think he excels in the quality of judgment. He is possessed of a sound judgment, which perceives truth with great clearness, and can trace it through the mazes of debate, without losing it....As a reasoner, he is remarkably perspicuous and methodical. He is a studious man, devoted to public business, and a thorough master of almost every public question that can arise, or he will spare no pains to become so, if he happens to be in want of information. What a man understands clearly, and has viewed in every different point of light, he will explain to the admiration of others, who have not thought of it at all, or but little, and who will pay in praise for the pains he saves them.” Fisher Ames to George Minot, 31 May 1789, Works of Fisher Ames, I, 35. And… “Maddison among the rest, Pouring from his narrow chest, More than Greek and Roman sense, Boundless tides of eloquence.” Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, Vol.8, p. 1684. James Madison (continued) Shy to the point of being inaudible to stenographers. Very frail and unhealthy. Shortest President of the United States. He was probably 5’3” tall or so. Described by Garry Wills as a gnome. Researched the history of ancient confederations on the assumptions of the Scottish Enlightenment. Quintessential Parliamentarian – Sized up the opposition before entering debates. Entered debates (including those at the Constitutional Convention) as the best prepared man on every point. Did he drink a pint of whiskey a day? (David Okrent, Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition.) But was Madison the Father of the Convention? Considered the “Father of the Constitution” but, according to one calculation, "of seventy-one specific proposals that Madison moved, seconded, or spoke unequivocally in regard to he was on the losing side forty times." Forrest McDonald, Novus Ordo Seclorum. Three major loses at the Convention: universal negative of all state laws, revisionary council (joint executive- judicial body to review laws), proportional representation in both branches of the government. But set the agenda for the Convention in the Virginia plan, took notes of the speeches at the Convention, wrote the most important Federalist Papers, lead the fight for ratification in Virginia, and secured passage of the Bill of Rights. James Wilson James Wilson (Madison’s Ally at the Convention) Fought with Madison for a universal negative of state laws, proportional representation in both branches, and a revisionary council. Considered the most democratic of the Federalists. Favored direct election of the President, Senate, and House. Foresaw the day when the President would be recognized by Americans as their spokesmen. Later became a Supreme Court judge George Washington’s Reputation and the Constitution George Washington and the Constitution Washington had promised to retire at the end of the Revolution, but Madison convinced him to preside over the Convention. (Did Madison really have to persuade him?) Washington served as the presiding President of the Convention and rarely spoke in debate. After the proceedings were over, he wrote a letter transmitting the Constitution to the Confederation Congress and the states for their consideration. This letter was often evoked during ratification. Washington did not actively participate in the ratification debate, but affirmed his support for the Constitution in his private correspondence. This private correspondence ended up getting published and used by Federalists. See DHRC, V, 788-790. The Venerable Franklin Benjamin Franklin Franklin was very old at the Convention (81), but lived another three years. He participated occasionally, having speeches he had written read for him by James Wilson. He made the famous observation that the sun on the wall is a rising sun, not a setting sun. Legend has it that he was also asked immediately after the Convention by a woman outside of Independence Hall what form of government had been created. He is said to have replied, “a republic, Madame, if you can keep it?” A Reform Caucus In Action The positions of delegates changed as the Convention progressed. Delegates learned from each other. Concessions in one areas led to rethinking in other areas. The convention was thus a “reform caucus in action” governed by a combination of interest (delegates advocating especially the interests of their states) and principle (delegates committed to different understandings of republicanism). The Virginia Plan Proportional Representation in both branches of the legislature. Number of delegates from each state would no longer be equal, but instead determined by their “quotas of contribution” or “number of free inhabitants.”[4] Lower House elected by the people and the Upper House by the lower House from nominations submitted by state legislatures. Independent Executive elected by the Legislature. Veto given to the National Government over state laws in areas where they were held to be incompatible with the articles of union. The New Jersey or Patterson Plan Unicameral legislature based upon equal representation for all states. Congress was given power to levy taxes and force their collection. Multi-person Executive was elected by the legislature. The Small States’ Case For Equal Representation Small states will be overpowered and outvoted by the large states without at least one branch in which they can protect their interests. The Confederation was based upon equal representation and this precedent should be followed. The Large States’ Case Against Equal Representation It violated the principles of equity and majority rule. It was not necessary to protect the small state interests. The small states had nothing to fear from a coalition of the large states because the large states had very dissimilar interests. States as states did not merit representation in the national government. The real and objective interests in the states were economic interests such as manufacturing, agricultural, and trading. Bradley Stevens’ Mural of the Great Compromise This mural by an American artist – Bradley Stevens – resulted from a resolution set forth by Christopher Dodd of Connecticut. It depicts Roger Sherman and Oliver Ellsworth who negotiated the “Connecticut” or “Great” Compromise. Since 2006, it has hung in the Capitol in the opulent Senate Reception room, celebrating this compromise as a victory for liberty. “The Great Extortion?” Was what is celebrated in our textbooks as “the Great Compromise” really an act of extortion? Small states refused to join the union without equal representation in one branch of the legislature. This was the Sine quo non (“without which, nothing”) presented by the small states as a condition of union. Slavery and the Constitution Southern states secure three favorable provisions for slavery: the three-fifths clause, the 1808 slave trade provision, and the fugitive slave clause. (More on this later). Core Principles of the Constitution Popular Sovereignty – Popular ratification of the Constitution and the “Federal Pyramid” based on successive filtrations of the public will. People directly elect the House of Representatives; people elect the state legislatures who elect the Senate. People or the state legislatures elect the Electors who elect the President; people indirectly elect the Senate and the Executive and together they appoint judges. Federalism – Division between the national and the state governments and state representation in the operations of the national government (Equal Representation in the Senate, the Electoral College, and the Amendment Process). National Supremacy – Over enumerated powers and those that can be implied from them. Signing the Constitution Forty one of the 55 delegates who attended at some time were present at the signing of the Constitution. Three refused to sign: Edmund Randolph, George Mason, and Elbridge Gerry. Thus, there were 38 delegates who signed the Constitution but 39 signatures. John Dickinson authorized fellow Pennsylvania delegate George Read to sign the Constitution for him. Benjamin Franklin’s Conciliatory Address "There are several parts of this Constitution which I do not at present approve, but I am not sure I shall never approve them. ... I doubt to whether any other Convention we can obtain, may be able to make a better Constitution. ... It therefore astonishes me, Sir, to find this system approaching so near to perfection as it does; and I think it will astonish our enemies..." Howard Chandler Christy’s Portrait of the Convention