Chapter 2: What is adventure programming?

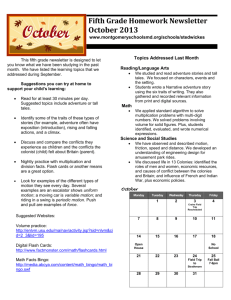

advertisement