CHP. 15- Mannerism and Later 16th Century in Italy

advertisement

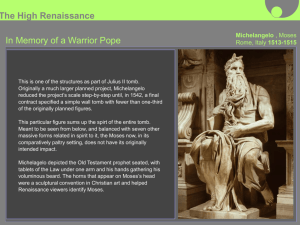

[CHP. 15- MANNERISM AND LATER 16TH CENTURY IN ITALY] P A G E |1 Overview of Mannerism (in webpages) Mannerism refers to a certain genre of literature, art, and architecture that evolved in Florence and Rome during the period from Raphael's death in 1520 to the beginning of the seventeenth century. This period is roughly that between the end of the High Renaissance and the beginning of the Baroque period. This was a period of political , economic , and religious upheaval. Rome had been sacked by the Germans and Spaniards. During the Reformation, the church lost its authority. Michelangelo and Raphael had enjoyed almost god-like status. kings begged them for sketches. During the Renaissance, all of the problems of portraying reality had been solved with art depicting harmony and perfection. What was to happen now? Mannerism would replace harmony with dissonance reason with emotion reality with imagination The artists following the Renaissance wanted to be original and so the Mannerist artists would abandon the realism based on observation -was a style that followed the Italian Renaissance which put emphasis on the individual style of the artist. -Most of the works from the period were constructed through the use of conventions Parmagianino, Madonna of the Long Neck, 1534 -elongated the human figure in order to make it more elegant -criticized in its time for putting too much emphasis on "style' Characteristics of Mannerism: rejection of classical harmony emphasis on imagination eccentricities versatility individual expression distortion of space elongation of the human figure. The Mannerists particularly enjoyed portraying allegorical images, as seen in Bronzino's Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time (1550). "Although the mannerists looked to the artists of the High Renaissance, such as Michelangelo and Raphael, as sources of inspiration, they did not concern themselves with the relationship between nature and appearance as these masters did. To the Mannerists, the art was in the abstracting and idealizing of the subject. Whereas artists such as Michelangelo had sought balance and harmony, the Mannerists sought instability, choosing to explore the possibilities for manipulation in their art. Characteristics of their style include the distortion of space and the elongation of the human figure." The young artists of Florence and Rome came to take the art of the older masters as model, particularly that of Michelangelo. But they were ambivalent, as young men often are toward a father figure, sometimes slavishly imitating him and at others turning to new and exaggerated stylizations. Michelangelo's figure, The Victor introduced a pose that became extremely popular with Mannerist sculptors—the corkscrew turn that moves away from the planar organization of most Renaissance figures into an intricate spiral composition. The spiral became a favorite device with the young sculptor Giovanni da Bologna who used it for The Rape of the Sabine Women (Figure 17-46). The exaggerated musculature of the figures in Moses Defending the Daughiers of Jethro (Figure 1740) by the young Rosso Fiorentino shows the influence of Michelangelo's figures from the Sistine (Figure 17-16). Michelangelo's figures of Night (Figure 17-27) and Dawn from the Medici tombs served as models for many young artists. Michelangelo himself used the figure of Night as model for a now lost painting of Leda and the Swan. The more elegant figure of Dawn was used by Benvenuto Cellini as model for the bronze figure of Diana that he cast for the French palace of Fontainebleau (Figure 1745). Like many other Mannerist artists, Cellini exaggerated the elegance of the original, lengthening the legs and torso and making the elegant head amazingly small. Mannerist nudes, which are often provocative and self-conscious, can be compared to the natural unself-conscious Renaissance nudes. Compare Bronzino's Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time (Figure 1742) to Titian's Allegory of Sacred and Profane Love (Figure 17-60). One is clear and well balanced while the other is complex and filled with tension. The various Mannerist explorations of space, form, and color are most pronounced in painting— the nervous line, twisted or oblique space, asymmetrical designs, eccentric compositions, thin or sour colors, disproportions and disturbed balances. Everything is held in a state of "dissonance, disassociation and doubt," to use scholar Wylie Sypher's phrase. Between 1520 and 1600 Europe was torn by contradictions; tormenting doubt made people oppose religious obedience to ardently held dogmatic principles. Mannerism is [CHP. 15- MANNERISM AND LATER 16TH CENTURY IN ITALY] P A G E |2 full of contradictions: rigid formality and obvious disturbance, bareness and over-elegance, mysticism and pornography. We can see these contradictions clearly when we compare works like Pontormo's Descent from the Cross (Figure 17-39) to Raphael's Deposition. It may be that the strange color combinations seen in Jacopo's Descent were based on some of Michelangelo's experiments. Compare Parmigianino's Madonna with the Long Neck (Figure 17-41) with Andrea del Sarto's High Renaissance Madonna of the Harpies (Figure 17-36) or with Giovanni Bellini's San Zaccaria Altarpiece (Figure 17-57). The Renaissance concern with balance, ease, and proportion and the High Renaissance pyramid composition are seen in both of the latter works, while the Parmigianino deliberately seems unbalanced, with large figures contrasted with small ones. Proportions are not natural, and if the Virgin stood up, she would be incredibly tall. Raphael's Portrait of Castiglione (Figure 17-18) can be contrasted to Bronzino's elegant Mannerist portrait (Figure 1743). Bronzino's portrait shows the rigid formality and mask-like face guarding the personality that was so typical of the mid-sixteenth-century Florentine court. How different is this from Raphael's portrait of Castiglione, which demonstrated the ideal Renaissance courtier, gracious, restrained, and in effortless control. Titian's portrait of the Man with the Glove (Figure 17-63) is much closer to Castiglione's sense of grace and ease than it is to the self-conscious elegance of the Mannerist portrait. Mannerist Painting (from wepages) rejection of the Classical traditions established for painting during the High Renaissance. The Mannerists particularly enjoyed portraying allegorical images consistent of mannerism are the dense crowded forms, play of lights and dark linear patterns Part --: Unit Exam Essay Questions (from previous Art 260-261 tests) (from AAT4) What effect did the Inquisition have on the visual arts? Which rules applied to the arts? Compare Mannerism with the High Renaissance style in Italy. Consider both context and formal elements. Compare the Sistine ceiling with the ceiling of the Palazzo del Tè. Consider subject, illusionism, context, and style. Describe the development of Palladio's architecture, discussing the influence of Vitruvius, Alberti, and the classical orders. Compare Veronese's Last Supper (Christ in the House of Levi) with that of Leonardo da Vinci. Consider style and iconography. Learning Goals (AAT4) After reading Chapter 15, you should be able to do the following: Identify the works and define the terms featured in this chapter Discuss the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation, and analyze their significance for the visual arts Compare Mannerism with the High Renaissance style Discuss Cellini's work from a biographical point of view Compare Giambologna's Mercury with Donatello's bronze David Discuss Vasari's views of women artists Discuss the role of mysticism, the mystic saints, and the Council of Trent in relation to the arts Explain Palladio's architectural use of Classical sources Describe the changes in church architecture resulting from the Counter-Reformation Chapter Outline (AAT4) MANNERISM AND THE LATER 16th CENTURY IN ITALY The Reformation: Martin Luther; Henry VIII Counter-Reformation Council of Trent (1545–1563) Veronese and the Inquisition Vasari, Lives (1550, 1568) Cellini, Autobiography Saint Teresa, The Way of Perfection Saint Ignatius Loyola, Spiritual Exercises Painters: Pontormo; Parmigianino; Bronzino; Fontana; Veronese; Romano; Anguissola; Tintoretto; El Greco Sculptors: Cellini; Giambologna; Properzia dé Rossi [CHP. 15- MANNERISM AND LATER 16TH CENTURY IN ITALY] P A G E |3 Architects: Romano; Palladio; Vignola (Il Gesù) Summary and Study Guide Define or identify the following terms: AAT4 Key Terms broken pediment a pediment in which the cornice is discontinuous or interrupted by another element. crossing the area in a Christian church where the transepts intersect the nave. cross-section a diagram showing a building cut by a vertical plane, usually at right angles to an axis. figura serpentinata a snakelike twisting of the body, typical of Mannerist art. keystone the wedge-shaped stone at the center of an arch, rib, or vault that is inserted last, locking the other stones into place. oculus a round opening in a wall or at the apex of a dome. rustication to give a rustic appearance to masonry blocks by roughening their surface and beveling their edges so that the joints are indented. triglyph in a Doric frieze, the rectangular area between the metopes, decorated with three vertical grooves (glyphs). volute in the Ionic order, the spiral scroll motif decorating the capital. voussoir one of the individual, wedge-shaped blocks of stone that make up an arch. Mannerism Mannerism is a term used to describe a certain genre of literature, art, and architecture that was produced during the period from Raphael's death in 1520 to the beginning of the seventeenth century, that is, between the end of the High Renaissance and the beginning of the Baroque period. Although the mannerists looked to the artists of the High Renaissance, such as Michelangelo and Raphael, as sources of inspiration, they did not concern themselves with the relationship be¬tween nature and appearance as these masters did. To the Mannerists, the art was in the abstracting and idealizing of the subject. Whereas artists such as Michelangelo had sought balance and harmony, the Mannerists sought instability, choosing to explore the possibilities for manipulation in their art. Characteristics of their style include the distortion of space and the elongation of the human figure. Mannerist Painting Rosso An example of the early Mannerist style in painting is Rosso Fiorentino's (1495-1540) Descent from the Cross (1521). Startling for its clambering forms, sharp edges, and harsh colors, this work, in effect, is a rejection of the Classical traditions established for painting during the High Renaissance. Jacopo Pontormo Jacopo Pontormo (1494-1557), a friend of Fiorentino, painted his own version of the subject shortly thereafter. In Pontormo's The Descent from the Cross (1525-1528), the figures are not in the center of the composition as tradition would dictate, but have been pushed away. Christ is posed in a somewhat contorted manner, and the space created is vague without cues to indicate its limits. Pontormo's colors, his distortion of the figures, and his composition contribute to the overall tension of this image, which, like Rosso's, represents an anti-Classical approach to painting. Parmigianino Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzuoli, better known as Parmigianino (1503-1540), created a work that reflects the manner of Raphael and of Leonardo as well. His painting The Madonna with the Long Neck (c. 1535) is much more elegant than Pontormo's The Descent from the Cross and exemplifies the direction that Mannerism would take. The elongated torso, hands, and neck of the Madonna add dramatic distortion to the composition and illustrate the Mannerists' focus upon those elements as vehicles of expression of idealized beauty. To the left of the Madonna, a cluster of figures gazes adoringly at her, while behind her, at some unidentified distance, stands an erect figure with a scroll. Agnolo Bronzino At its most elegant level, the style of the Mannerists appealed to the taste of the aristocracy, especially in the form of portraits. The painting Portrait of a Young Man (1550) [see illustration 6], and the portrait Eleanora of Toledo and Her Son Giovanni de' Medici (c. 1550), by Agnolo Bronzino (1503-1572), the court painter of Cosimo I de' Medici, possess many of these desired qualities. These two paintings by Bronzino, though of real persons, do not seem to represent the in¬dividuals as much as their position in society. [CHP. 15- MANNERISM AND LATER 16TH CENTURY IN ITALY] P A G E |4 The Mannerists particularly enjoyed portraying allegorical images, as seen in Bronzino's Venus, Cupid, Folly, and Time (1550). Here again, special attention has been paid to the heads and the hands to accentuate their expressive qualities. The figures are sensuously modeled and so fill the composition that little of the space surrounding them is revealed. Tintoretto It was not until the middle of the sixteenth century that the Man¬nerist style was seen in Venice, where Jacobo Robusti Tintoretto (1518¬1594) was respected as a Mannerist painter. Although his painting Christ Before Pilate (1566-1567) has qualities that recall Raphael's use of light and shadow and color, the figures and the atmosphere are distinctly Mannerist. If Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper is considered to be the classical version of that subject, then Tintoretto's version of The Last Supper (1592-1594) is its antithesis. Tintoretto has placed the table on a strong diagonal axis. Christ is at the center, but because of the perspective his figure is small and would not stand out were it not for the halo that envelops him. Earthly qualities are introduced in the form of servants milling about while the Apostles converse with one another. As Christ conducts the Passover ceremony, smoke from an oil lamp overhead is transformed into heavenly beings who gravitate toward him. Although Tintoretto has chosen to focus upon the ritual of Passover rather than Christ's announcement that he will be betrayed, the overall effect of the composition is one of extreme drama. El Greco One of the last, and probably the most famous, of the Mannerist painters who studied in the Venetian School was Domenikos Theotocopoulos (1541-1614), better known as El Greco. One of his best-known works is The Burial of Count Orgaz (1586). Though this huge painting, sixteen feet tall and nearly twelve feet wide, recounts an event that took place more than two centuries earlier, El Greco took the liberty of depicting, among those present, individuals from the Church and aristocracy who were his contemporaries. The painting is set into the wall of the chapel of the Church of Santo Tome in Toledo, Spain, directly above a stone plaque that represents the sarcophagus of Count Orgaz. The effect is powerful, for one is faced with an image of the count being lowered into his resting place, while above, his soul is carried up to heaven and Christ. Besides his religious painting, El Greco was renowned as a portrait painter, as evidenced in his portrait of Fray Felix Hortensio Paravicino (c. 1605). Though the painting is similar in some ways to Titian's Man with the Glove (1520), the subject's intense expression is made even stronger by El Greco's sensitive treatment of his hands and face. However, it was the elongated manner in which El Greco depicted the human figure for which he is probably best known, and his paintings The Vision of St. John (1610) and Christ on the Cross with Landscape (1610) well illustrate this style. In the former painting, the elongated features of the figures reaching upward accent their movement and the tension they possess. The image does not pretend to represent an actual event but rather a vision, and the unearthly quality of the work is apparent. In the latter work, the, elongation of Christ's torso and limbs conveys a sense of weightlessness; he seems to float upon, rather than hang from, the cross. Mannerist Sculpture Benvenuto Cellini The work of Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571) is representative of the Mannerist style of sculpture. His Diana of Fontainebleau (1543¬1544), cast in bronze, is larger than life-size. In proportion to the rest of her body, her head seems small, whereas her arms and legs are elongated, accenting her reclining contrapposto position. Giovanni da Bologna Giovanni da Bologna (1529-1608) is considered by some his¬torians to be the greatest Italian sculptor after Michelangelo. His work The Rape of the Sabine Woman, so named after it was completed in 1583, reflects the artist's compliance with and rejection of Mannerist principles. The three figures that make up the sculpture are intertwined; an old man cowers below with his left arm raised defensively, while a young man stands above him holding a woman who has flung her left arm out. Bologna was very conscious of his use of both positive and negative space. As one views the sculpture from different angles, one becomes aware of the spaces between the figures as well as of their mass. The sculpture is self-contained in that it carries its own space with it, rather than extending out and sharing that space with the viewer. Like Michelangelo, Bologna is able to depict a moment of movement involv¬ing figures that appear to be capable of action. Mannerist Architecture Giulio Romano Closely associated with the Mannerist style of architecture is the painter and architect Giulio Romano (1499-1546), who served as Raphael's assistant while he was working on the Vatican stanza for Pope Julius II. In 1524, several years after Raphael's death, Romano moved to Mantua, where he received a commission to build the Palazzo del Te' (1525-1535) for Duke Federigo Conzaga. What Conzaga desired was a palazzo that would serve not only as a summer palace but also as a stud farm for his stable of horses. Dispensing with the High Renaissance tradition of using a central portal to emphasize the main axis of a building, Romano designed a structure that had its entrance on the west, with a large garden bordered by the stables facing the east. His treatment of the structure itself overtly ignored and at the same time parodied the Classical traditions concern¬ ing construction and symmetry. [CHP. 15- MANNERISM AND LATER 16TH CENTURY IN ITALY] 16th Century Christianity was added to Platonic ideal: Neo-platonism. Michelangelo in the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and Raphael in the Vatican Stanze are representative of this movement at the beginning of the 16th century; they brought the Renaissance to the highest achievement in painting in Rome. But the attempt to reconcile paganism and Christianity foundered. The Reformation intervened and the works of the Mannerists show what resulted in painting. The Counter-Reformation ushered in the new period, the Baroque. P A G E |5