d - Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences

advertisement

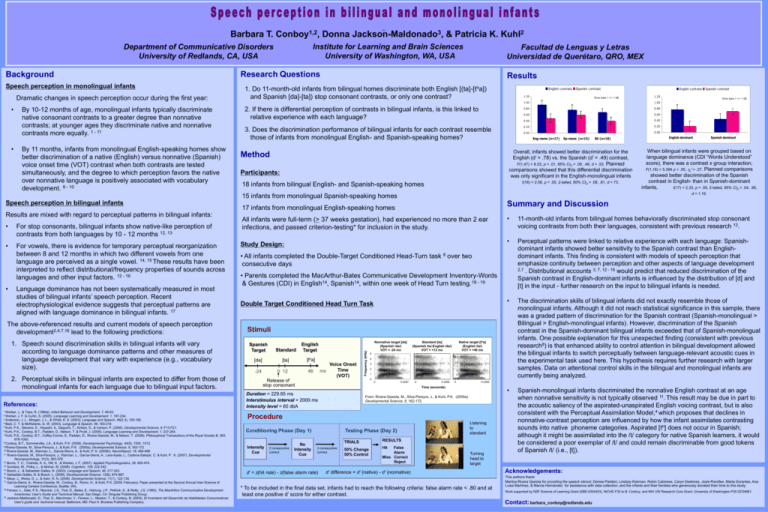

Y9062 Barbara T. Conboy1,2, Donna Jackson-Maldonado3, & Patricia K. Kuhl2 Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences University of Washington, WA, USA Speech perception in monolingual infants Dramatic changes in speech perception occur during the first year: • By 10-12 months of age, monolingual infants typically discriminate native consonant contrasts to a greater degree than nonnative contrasts; at younger ages they discriminate native and nonnative contrasts more equally. 1 - 11 • By 11 months, infants from monolingual English-speaking homes show better discrimination of a native (English) versus nonnative (Spanish) voice onset time (VOT) contrast when both contrasts are tested simultaneously, and the degree to which perception favors the native over nonnative language is positively associated with vocabulary development. 8 - 10 Research Questions Results 1. Do 11-month-old infants from bilingual homes discriminate both English [(ta]-[tha]) and Spanish [da]-[ta]) stop consonant contrasts, or only one contrast? English contrast Spanish contrast 1.20 2. If there is differential perception of contrasts in bilingual infants, is this linked to relative experience with each language? mean d' Background Facultad de Lenguas y Letras Universidad de Querétaro, QRO, MEX 3. Does the discrimination performance of bilingual infants for each contrast resemble those of infants from monolingual English- and Spanish-speaking homes? 1.00 1.00 0.80 0.80 0.60 0.40 Participants: 18 infants from bilingual English- and Spanish-speaking homes 0.00 0.00 Bil (n=18) • • • For stop consonants, bilingual infants show native-like perception of contrasts from both languages by 10 - 12 months 12, 13 For vowels, there is evidence for temporary perceptual reorganization between 8 and 12 months in which two different vowels from one language are perceived as a single vowel. 14, 15 These results have been interpreted to reflect distributional/frequency properties of sounds across languages and other input factors. 12 - 16 Language dominance has not been systematically measured in most studies of bilingual infants’ speech perception. Recent electrophysiological evidence suggests that perceptual patterns are aligned with language dominance in bilingual infants. 17 The above-referenced results and current models of speech perception development2,4,7,16 lead to the following predictions: 1. Speech sound discrimination skills in bilingual infants will vary according to language dominance patterns and other measures of language development that vary with experience (e.g., vocabulary size). 2. Perceptual skills in bilingual infants are expected to differ from those of monolingual infants for each language due to bilingual input factors. References: 1 Werker, J., & Tees, R. (1984a). Infant Behavior and Development, 7, 49-63. J. F. & Curtin, S. (2005). Language Learning and Development, 1, 197-234. 3 Anderson, J. L., Morgan, J. L., & White, K. S. (2003). Language and Speech, 46(2-3), 155-182. 4 Best, C. T. & McRoberts, G. W. (2003). Language & Speech, 46, 183-216. 5 Kuhl, P.K., Stevens, E., Hayashi, A., Deguchi, T., Kiritani, S., & Iverson, P. (2006). Developmental Science, 9, F13-F21. 6 Kuhl, P.K., Conboy, B.T., Padden, D., Nelson, T. & Pruitt, J. (2005). Language Learning and Development, 1, 237-264. 7 Kuhl, P.K., Conboy, B.T., Coffey-Corina, S., Padden, D., Rivera-Gaxiola, M., & Nelson, T. (2008). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 363, 979-1000. 8 Conboy, B.T., Sommerville, J.A., & Kuhl, P.K. (2008). Developmental Psychology, 44(5), 1505 -1512. 9 Rivera-Gaxiola, M., Silva-Pereyra, J., & Kuhl, P.K. (2005a). Developmental Science, 8, 162-172. 10 Rivera-Gaxiola, M., Klarman, L., Garcia-Sierra, A., & Kuhl, P. K. (2005b). NeuroReport, 16, 495-498. 11 Rivera-Gaxiola, M., Silva-Pereyra, J., Klarman, L., Garcia-Sierra, A., Lara-Ayala, L., Cadena-Salazar, C. & Kuhl, P. K. (2007). Developmental Neuropsychology, 31(3), 363-378. 12 Burns, T. C., Yoshida, K. A., Hill, K., & Werker, J. F. (2007). Applied Psycholinguistics, 28, 455‐474. 13 Sundara, M., Polka, L., & Molnar, M. (2008). Cognition, 108, 232‐242. 14 Bosch, L., & Sebastian‐Galles, N. (2003). Language and Speech, 46, 217‐243. 15 Sebastián-Galles, N. & Bosch, L. (2009). Developmental Science, 12(6), 874-887. 16 Maye, J., Weiss, D. J., & Aslin, R. N. (2008). Developmental Science, 11(1), 122‐134. 17 García-Sierra, A., Rivera-Gaxiola, M., Conboy, B., Romo, H., & Kuhl, P.K. (2009, February). Paper presented at the Second Annual Inter-Science of Learning Centers Conference, Seattle, WA.. 18 Fenson, L., Dale, P.S., Reznick, J.S., Thal, D., Bates, E., Hartung, J.P., Pethick, S., & Reilly, J.S. (1993). The MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories: User’s Guide and Technical Manual. San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing Group. 19 Jackson-Maldonado, D., Thal, D., Marchman, V., Fenson, L., Newton, T., & Conboy, B. (2003). El Inventario del Desarrollo de Habilidades Comunicativas: User’s guide and technical manual. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company. 2 Werker, All infants were full-term (> 37 weeks gestation), had experienced no more than 2 ear infections, and passed criterion-testing* for inclusion in the study. Study Design: 11-month-old infants from bilingual homes behaviorally discriminated stop consonant voicing contrasts from both their languages, consistent with previous research 12. • Perceptual patterns were linked to relative experience with each language: Spanishdominant infants showed better sensitivity to the Spanish contrast than Englishdominant infants. This finding is consistent with models of speech perception that emphasize continuity between perception and other aspects of language development 2,7 . Distributional accounts 3, 7, 12 - 16 would predict that reduced discrimination of the Spanish contrast in English-dominant infants is influenced by the distribution of [d] and [t] in the input - further research on the input to bilingual infants is needed. • The discrimination skills of bilingual infants did not exactly resemble those of monolingual infants. Although it did not reach statistical significance in this sample, there was a graded pattern of discrimination for the Spanish contrast (Spanish-monolingual > Bilingual > English-monolingual infants). However, discrimination of the Spanish contrast in the Spanish-dominant bilingual infants exceeded that of Spanish-monolingual infants. One possible explanation for this unexpected finding (consistent with previous research8) is that enhanced ability to control attention in bilingual development allowed the bilingual infants to switch perceptually between language-relevant acoustic cues in the experimental task used here. This hypothesis requires further research with larger samples. Data on attentional control skills in the bilingual and monolingual infants are currently being analyzed. • Spanish-monolingual infants discriminated the nonnative English contrast at an age when nonnative sensitivity is not typically observed 11. This result may be due in part to the acoustic saliency of the aspirated-unaspirated English voicing contrast, but is also consistent with the Perceptual Assimilation Model,4 which proposes that declines in nonnative-contrast perception are influenced by how the infant assimilates contrasting sounds into native phoneme categories. Aspirated [th] does not occur in Spanish; although it might be assimilated into the /t/ category for native Spanish learners, it would be considered a poor exemplar of /t/ and could remain discriminable from good tokens of Spanish /t/ (i.e., [t]). • Parents completed the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory-Words & Gestures (CDI) in English14, Spanish14, within one week of Head Turn testing.18 - 19 Double Target Conditioned Head Turn Task Stimuli Standard [da] [ta] [tha] Voice Onset Time ms (VOT) 46 0 12 -24 English Target Nonnative target [da] (Spanish /da/) VOT = -24 ms Native target [tha] (English /ta/) VOT = +46 ms Standard [ta] (Spanish /ta/,English /da/) VOT = +12 ms 5 4 3 2 1 0 Release of stop consonant 0 0.2297 0 0.2292 0 0.2300 Time (seconds) Duration = 229.65 ms Interstimulus interval = 2000 ms Intensity level = 65 dbA From: Rivera-Gaxiola, M., Silva-Pereyra, J., & Kuhl, P.K. (2005a). Developmental Science, 8, 162-172. Procedure Conditioning Phase (Day 1) Intensity Cue 2 consecutive correct No Intensity Cue Testing Phase (Day 2) 3 consecutive correct d’ = z(hit rate) - z(false alarm rate) When bilingual infants were grouped based on language dominance (CDI “Words Understood” score), there was a contrast x group interaction, F(1,16) = 5.394 p < .05, p2 = .27. Planned comparisons showed better discrimination of the Spanish contrast in English- than in Spanish-dominant infants, t(17) = 2.33, p < .05, 2-tailed, 95% CID = .04, .95, • • All infants completed the Double-Target Conditioned Head-Turn task 8 over two consecutive days Spanish Target Spanish dominant Summary and Discussion 17 infants from monolingual English-speaking homes Frequency (kHz) Results are mixed with regard to perceptual patterns in bilingual infants: English dominant d = 1.19. 15 infants from monolingual Spanish-speaking homes Speech perception in bilingual infants 0.40 0.20 Sp-mono (n=15) Error bars = +/- 1 SE 0.60 0.20 Eng-mono (n=17) Spanish contrast 1.20 Error bars = +/- 1 SE Overall, infants showed better discrimination for the English (d’ = .78) vs. the Spanish (d’ = .49) contrast, F(1,47) = 8.33, p < .01, 95% CID = .09, .48, d = .53. Planned comparisons showed that this differential discrimination was only significant in the English-monolingual infants t(16) = 2.58, p < .05, 2-tailed, 95% CID = .08, .81, d = 73. Method English contrast mean d' Department of Communicative Disorders University of Redlands, CA, USA TRIALS RESULTS 50% Change 50% Control Hit False Alarm Miss Correct Reject Listening to standard Turning head to target d’ difference = d’ (native) - d’ (nonnative) * To be included in the final data set, infants had to reach the following criteria: false alarm rate < .80 and at least one positive d’ score for either contrast. Acknowledgements: This authors thank: Maritza-Rivera Gaxiola for providing the speech stimuli; Denise Padden, Lindsay Klarman, Robin Cabiness, Caryn Deskines, Josie Randles, Marta Dorantes, Ana Luisa Martínez, & Marcia Hernández for assistance with data collection; and the infants and their families who generously donated their time to this study. Work supported by NSF Science of Learning Grant (SBE-0354453), NICHD F32 to B. Conboy, and NIH UW Research Core Grant, University of Washington P30 DC04661. Contact: barbara_conboy@redlands.edu