cognitive processes

advertisement

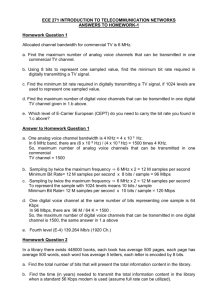

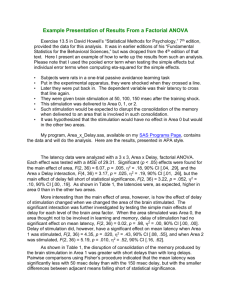

The Growth of Cognitive Modeling in HumanComputer Interaction Since GOMS By Judith Reitman Olson and Gary M. Olson The University of Michigan Introduction Published in 1990 by professors at the University of Michigan Developed a Framework for predicting how a user will interact with a design -> a useful tool for designers. Summarizes the work of Card, Moran, and Newell (1980s, 1980b, 1983) in this area The Human Side of Human Computer Interaction Each of the three types of processes: perceptual, cognitive, and motor How GOMS could be used as a cognitive process Lots of quantitative data, which is good Modifications to designs using those numbers Many unanswered questions remain Computer Based Tasks Illustrated 2 Parts to the Framework Presented 1st Piece of the Framework Model Human Processor (MHP), summarizes a large body of research from cognitive psychology 2nd Piece of the Framework: The GOMS modelactually a family of models - describes the knowledge necessary and the four cognitive components of skilled performance in tasks: goals, operators, methods, and selection rules. Roles of Cognitive Models 1. Constrains the design space 2. Answer specific design decisions 3. Estimate the total time for task performance with sufficient accuracy 4. Provide a base to calculate training time and to guide training documentations 5. Discover which stage of activity takes the longest time or produces the most errors GOMS Predicts user methods and operators Calculates the time needed for a task To make useful predictions, GOMS assumes that routine cognitive skills can be described as a serial sequence of cognitive operations and motor activities Consists of time parameters. Consistent across tasks -> text editors, graphics systems, and some functions from the operating system of a variety of software Limitations of GOMS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. Does not account for nonskilled users Does not account for learning and recall Does not account for errors Little distinction between cognitive processes Does not account for parallel processing Does not address mental workload Does not address functionality Does not address user fatigue Does not account for individual differences Does not account for user’s acceptance Does not address organizational life Plan of the Article How quantitative results helped future work How some investigators took the work into new directions: the study of learning and transfer, the study of errors, and the analysis of parallel processes. The limitations that still remain in cognitive models of HCI Results of Empirical Testing 1.) A keystroke, called k, for a midskilled typist is 280 msec. 2.) A mental operator, called M, often interpreted as the time to retrieve the next chuck of information from long-term memory into WM, is 1.35s. 3.) Pointing, called P, to target on a small display with a mouse takes on average 1.1 sec (though the time is variable according to Fitts’s law) 4.) Moving the hands, called H, from the keyboard to the mouse takes 400 msec Modeling Specific Serial Components Empirical explorations Derived detailed time parameters As mentioned in the introduction, there are three general classes: Motor Movements Perception Memory and Cognition Researchers CMN = Card, Moran, and Newell, 1983 O&N = Olson and Nilsen, 1988 J&N = John and Newell, 1989 WSN = Walker, Smelcer, and Nilsen, 1988 Motor Movements Keying Time it takes to enter a keystroke Value depends on skill of typist Some parameters (CMN) Best Typist: 80 msec Good Typist: 120 msec Average Typist: 200 msec Typing random letters: 500 msec Typing complex codes: 750 msec Worst Typist: 1200 msec Motor Movements Keying Parameters for Spreadsheets (O&N) Entering spreadsheet formulas Entering column / width commands Lotus1: 330 msec Multiplan2: 220 msec Lotus: 280 msec Multiplan: 230 msec Other Parameters (J&N) Enter command abbreviations: 230 msec Expert typing cross-hand digraphs: 170 msec Expert typing same-hand digraphs: 220 msec 1Lotus 1-2-3 is a spreadsheet program from Lotus Software (now part of IBM). It was the IBM PC's first killer application; its huge popularity in the mid-1980s contributed significantly to the success of IBM PC in the corporate environment 2Multiplan was an early spreadsheet program, following VisiCalc, developed by Microsoft. Introduced in 1982, initially for computers running CP/M, it was ported to a number of other operating systems including MS-DOS and Xenix. Motor Movements Moving a Mouse Time it takes to point to a target with a mouse Time varies depending on: Distance Size Value may be outdated, since the research is done on older displays. Motor Movements Moving a Mouse Parameters for Menu Selection (CMN): Parameters for Nested-Menu Selection (WSN): Average value, small screen, menu shaped target: 1100 msec Variation in distance and size: 1.0 + 0.10 log2(D/S+0.5) sec Average value, small screen, menu shaped target: 1900 msec Variation in distance and size: 0.80 + 0.23 log2(D/S+0.5) sec Fritts’ Law: T = 1.03 + 0.96 log2(D/S+0.5) sec Motor Movements Moving a Mouse Walker et al. used these results to make three adjustments to the design of menus Goal is to shorten menu selection time Three adjustments: Menu pops up to the right of the cursor instead of below Menu targets grow as the distance from the cursor’s staring position increases Virtual borders on the top, right, and bottom edges of a pop up menu Walker et al.’s Work: Motor Movements Hand Movements Time needed to move from the spacebar of a keyboard until the pointing control begins to move the cursor Varies depending on pointing device Parameters To To To To Mouse: 360 msec Joystick: 260 msec Cursor(arrow) Keys: 310 msec Function Keys: 320 msec Perception Time needed to recognize or perceive an item on screen Parameters Time to respond to brief light: 100 msec Varies with intensity of light (brighter is faster): 50 – 200 msec Recognize a 6-letter word: 314 msec Saccade (Jump to a new location): 230 msec Perception Olson and Nilsen used these parameters to derive the time needed to store a label into working memory. Calculation A saccade to the row line: 230 msec A storage of the row label: 130 msec A saccade to the column head: 230 msec A storage of the column label: 130 msec A saccade to the cell in which typing is to start: 230 msec Retrieval of the row and column labels: 1350 msec Total: 2300 msec Memory and Cognition Memory Retrieval Time needed to retrieve information from long term memory (LTM) to working memory (WM) Varies depending on type of information Retrieval of same command is proved to be quicker Memory and Cognition Memory Retrieval Parameters Retrieve a command name or delimiter: 1350 msec Retrieve a random command abbreviation: 1200, 1209, 1200 msec Retrieve the next part of a formula Retrieve command part in column width task Multiplan (cursor method): 1100 msec Lotus (cursor method): 990 msec Lotus (typing method): 1350msec Multiplan: 1160 msec Lotus: 1080 msec Repeated retrieval of same command Lotus: 660 msec Memory and Cognition Executing Steps in a Task Time needed to perform a mental step Although there are different types of mental steps, the results were remarkably consistent across studies Memory and Cognition Executing Steps in a Task Parameters Cognitive Processor (the contents of WM initiate associatively-linked actions in LTM): 70 msec Execute next rule in a formal model of skilled performance: 100 msec Execute next step in decoding abbreviations: 66, 60, 50 msec Memory and Cognition Choosing Methods Time needed to choose a method of action Card assumes that the more choices for a response, the longer the expected response time Different studies vary significantly, which indicates that choosing methods is a complex cognitive task Predicting Composite Performance Example 1 Typing in values then pointing to next cell with a mouse Parameters Moving the hand to the mouse: 360 msec Clicking the mouse (same as a keystroke): 230 msec Moving the hand to the keyboard: 360 msec Retrieving two digits: 1200 msec Typing two digits @ 230 each: 460 msec Retrieving the end action: 1200 msec Typing the <ret> key: 230 msec Total: 4040 msec Real results: 4.19 sec Error: 3% Predicting Composite Performance Example 2-1 Typing in values, clicking enter to go to next cell. Use mouse only to move to next line Parameters for moving the mouse Moving hand to mouse: 360 msec Pointing to a new line with mouse: 1500 msec Clicking the mouse: 230 msec Moving hand to keyboard: 360 msec Total: 2450 msec Real results: 2.81 sec Error: 13% Predicting Composite Performance Example 2-2 Typing in values, clicking enter to go to next cell. Use mouse only to move to next line Parameters for typing each number into the cell Retrieving (or looking for) two digits: : 1200 msec Typing two digits @ 230 msec each: 460 msec Retrieving the end action: 1200 msec Typing the <ret>: 230 msec Total: 3090 msec Real results: 2.46 sec Error: 26% Predicting Composite Performance Summary The performance could be challenged, especially the mental operations Average error is within 14% of the observed value, means it’s still useful in design Example Based on the Summary of Findings Example – Time Prediction for Emailing Yourself Action Saccade to Browser "To" section + perceive + point with mouse Time (msec) 1830 Click on Browser "To" section 230 Move hand to keyboard 360 Type in 16 characters "dpfister@uci.edu" Move hand to mouse Saccade to subject section + perceive + point with mouse 3680 1830 230 Move hand to keyboard 360 Move hand to mouse (230 * 16) 360 Click on subject section Type in 11 characters "Hello World" (230 + 100 + 1500) 2530 360 (230 + 100 + 1500) (230 * 11) Calculations (continued) Saccade to message body section + perceive + point with mouse 1830 Click on the message body section 230 Move hand to keyboard 360 Type in 11 characters "Hello World" Move hand to mouse Saccade to send button + perceive + point with mouse Click on stopwatch Saccade to stopwatch + perceive + point with mouse Click on stopwatch Total 2530 (230 + 100 + 1500) (230 * 11) 360 1830 (230 + 100 + 1500) 230 1830 (230 + 100 + 1500) 230 19370 (19 seconds) Extensions of the Basic Framework Classes of extension Grammars (TAG) Production Systems Learning and Transfer Analysis of Errors Parallel Processes Critical Path Analysis Classes of extension Grammars Task-Action Grammar Consist of goals, rules, and action Goals are translated into action by rules Production Systems Consist of rules Similar to grammar, makes things more explicit Can determine the number of loads needed to be stored in WM to perform an action Example of TAG Example of Production Systems Learning and Transfer Time to Learn Cognitive Complexity Theory Time needed to learn a production system step Time needed to learn a TAG rule Kieras and Polson: 30 s Ziegler, Vossen, and Hoppe: 17 s Card: 20 s Current “Best Guess”:25 s No quantified results Shown that 28 well-known rules was learned nearly 3 times faster than 12 complicated rules Varies depending on learning situation (e.g. amount of given explanation) Learning and Transfer Transfer of Training from One System to Another Learning times same order of magnitude over many situations and experiments. Consistency in design is key -> number of rules not as important as experience carryover. Analysis of Errors Multiple causes of error WM overflow Length of time item remains in WM Research shows that errors increases as WM load increases Still a lot of room for research, but a good start People forget the crucial “join” statement at the end of an SQL query when lots of items are in WM. Parallel Processes Previous analysis (GOMS) assumes actions are performed in sequence People type faster two successive letters on different hands than different letters with the same hand - indicates the presence of parallel process Situations for parallel process User experiences multiple external signals in parallel Mental events that occur in parallel External actions that occur in parallel GOMS calculates a clerk need 2 s to type in 1 item, but in reality, they need less than .5 s Critical Path Analysis Finds the path of events that a user takes Predicts time for parallel processes Harder to examine than serial process Example: Critical path of a world-class typist: 30 msec Critical path of a regular typist: 200 msec Need to identify critical paths that take the most time – can ignore tasks that take shorter time than others if they are performed in parallel. Future Research Directions (1990) Nonskilled or Casual User [GOMS only considers experienced users] Learning [GOMS only considers experienced users] Errors and Mental Workload [GOMS does not account for potential errors in time calculations] Cognitive Process [GOMS does not account complex mental operations] Parallel Processes [GOMS does not account for this] Individual Differences [Not in GOMS] Cognitive Modeling in HumanComputer Interaction Unanswered issues: Fatigue Acceptance of system Functions Still useful for many applications, especially in systems that require repetitive actions Conclusion Cognitive models can screen out certain classes of poor designs that involve highly repetitive and stylized tasks Based on simple case study we did, principles appear to be sound, and these principles are useful especially in the early design stages