Teacher-created Units - Collaborative for Educational Services Tour

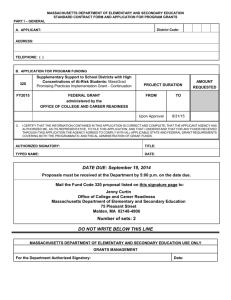

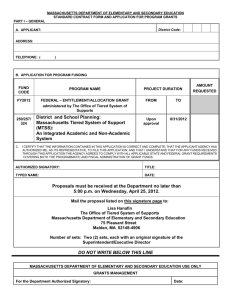

advertisement