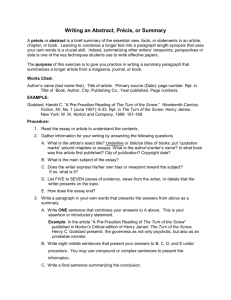

Voltaire's tale of how Candide — young, naive, and not too bright

Honors World Literature

Background for Candide

Voltaire’s tale of how Candide — young, naive, and not too bright — endures a series of trials, travels, and misadventures as he searches for his beloved Cunegonde was a publishing sensation in Europe in 1759. Some 20,000 copies were printed in that year alone, confirming its status as a bestseller in the context of that era. The satirical treatments of religion, sexuality, and authority made Candide both a target of censorship by governments and the church as well as a hugely popular underground success. Over the centuries, the tale has been imitated, augmented with further adventures, illustrated more than a hundred times by artists anonymous and famous, adapted into various other art forms, translated into all the major languages of the world, and canonized as an outstanding contribution to both French and world literature.

Voltaire: A Brief Life

The French philosopher, poet, playwright, and novelist François-Marie Arouet (November 21, 1694–May 30, 1778) — pen name, Voltaire — was foremost among the 18th-century philosophes and a passionate crusader for humanism, justice, and free thought. One of the towering figures of the European Enlightenment, and the first writer to achieve, in his lifetime, what today we would call the status of a celebrity, he enjoyed a readership that spanned Europe and the British

Isles, and extended to the New World. Through the 2,000 works he published, he exerted a heretofore unmatched level of influence on public opinion.

Born of a middle-class Parisian family, Voltaire was educated at a Jesuit school and gave up his legal studies for writing. Early literary creations, including the tragic dramas Oedipe (1718) and Zaïre (1732) and the epic poem La Henriade (1728), earned him a reputation among contemporaries as the premier poet and playwright of his century. Both admired and condemned for his liberal views and attacks on the church, nobility, and the ancien régime

, he was imprisoned and exiled on several occasions.

Banished to England from 1726 to 1729, Voltaire was drawn to the political ideas of

John Locke, Isaac Newton, and others, about which he wrote in Letters Concerning the English Nation [Lettres philosophiques, 1734]. The book was banned in France, and Voltaire took refuge at the estates of wealthy admirers. His place in history rests chiefly on his essays and letters in defense of reason and tolerance, and on such

“philosophical tales” as Zadig (1747) and Candide (1759).

By the 1750s, disenchantment with his situation in France led him to accept an invitation to take up residence in Potsdam at the court of the Prussian King Frederick the Great. Becoming disenchanted with Frederick as well, Voltaire took his leave of

Potsdam, settling first in Geneva and then, in 1758, on an estate he created in the village of Ferney, just over the Swiss border. It was there, when Voltaire was 65 years old, that he wrote Candide . He remained at Ferney until returning to Paris in triumph in February 1778, when he was 83. In the months that followed,

Voltaire met Benjamin Franklin, had a new play produced at the Comédie-Française, and was feted throughout the French capital. Voltaire died in a house on what is now called the Quai Voltaire on May 30, 1778. During the French Revolution, his remains were interred in the Panthéon in Paris amidst a vast public spectacle, stage managed by the great painter

Jacques-Louis David. Other major works include Essay on the Manners and Spirit of Nations [Essai sur les moeurs et l’ésprit des nations, 1756–69], a seven-volume world history, and

Philosophical Dictionary [Dictionnaire philosophique,

1764], a compendium of ideas.

Candide: Plot, Major Characters, and Adaptations

Candide, or Optimism

( Candide, ou L’optimisme , 1759)

Voltaire's "philosophical tale" ( conte philosophique ) follows the adventures and misadventures of its open-hearted, innocent, and extremely gullible title character, who has been instructed in Leibnizian optimism by his master, Dr. Pangloss, whose credo that this is "the best of all possible worlds" has been humorously but effectively shredded by story's end.

Characters

Abbé of Périgord A cleric from the district of Périgord in southwestern France whom Candide and Martin meet when they first arrive in Paris. This "ever alert, officious, forward, fawning, and complaisant" busybody takes it upon himself to show Candide the town.

Cacambo Formerly a singing-boy, sacristan, sailor, monk, peddler, soldier, and servant, this clever, resourceful, and "very honest fellow" becomes Candide's faithful valet and eventually settles with his master and the rest of the company on the little farm just outside of Constantinople.

Candide

Naive title character in Voltaire’s riotous satire. After a series of disastrous adventures have sorely tried his belief in the optimistic doctrines of his teacher Dr. Pangloss, Candide settles down with Pangloss, his beloved Cunegonde, and other companions of his wanderings, certain of one essential truth, that man must cultivate his garden.

Cunegonde Beautiful and pragmatic daughter of the Baron Thunder-ten-Tronckh of Westphalia and beloved of Candide. When she and Candide are found together, Candide is expelled from her father’s castle, and spends much of the tale searching for her. Meanwhile, Cunegonde undergoes severe trials of her own.

Dr. Pangloss

Professor of “metaphysico-theologico-cosmolo-nigology” and tutor to Candide, he steadfastly espouses the doctrine that “all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds,” despite repeated confrontations with natural disasters and human depravity. His “optimism” is modeled on the philosophy of German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), as popularized by Alexander Pope (“Whatever is, is right,” from An Essay on Man , 1732–34).

James, the Good Anabaptist A kindly man who — unlike his hardhearted neighbors — takes pity on Candide in

Holland, treating the starving young man with "extreme generosity."

Martin A poor but honest man of letters whose life experiences ("robbed by his wife, beaten by his son, and abandoned by his daughter") have given him a rather jaundiced view of human nature. He travels to Europe from Surinam with

Candide, who enjoys discussing philosophical matters with the elderly philosopher, who describes himself as a

Manichaean.

Paquette and Friar Giroflée

Chambermaid to the mother of Cunegonde, the Baroness of Thunderten-Tronckh, Paquette contracts a social disease (which she passes on to Dr. Pangloss) and is expelled from the castle. After a series of misfortunes, she becomes the companion of Friar Giroflée, a most unhappy monk who was forced at the age of fifteen to "put on this detestable habit" to

"increase the fortune of a cursed older brother."

The Baron/The Reverend Father Commandant The son of the Baron Thunder-ten-Tronckh of Westphalia and

Cunegonde's brother. Handsome and haughty, he is extremely proud of his family's aristocratic lineage and twice refuses to allow Candide to marry his sister.

The Old Woman Formerly a great beauty, she is the daughter of Pope Urban X and the Princess of

Palestrina. Brought up in a palace, she is betrothed at a young age to a handsome prince, who unfortunately is poisoned by a former mistress before his marriage. This is only the first of an almost unbelievable string of disasters to befall the woman who will nurse Candide back to health, reunite him — albeit temporarily — with Cunegonde, and become one of his trusted traveling companions.

Introduction

On his travels in search of Cunegonde, his lost love, Voltaire’s Candide encounters a world marked by political and religious upheaval, scientific discovery, and colonial expansion. His tutor, Dr. Pangloss, insists that “all is for the best,” but episodes of tragedy and devastation continually challenge this optimism.

Candide is a work of fiction, but it is not a novel. Its zany and often ridiculous two-dimensional characters, and its improbable, rapid plot twists, cannot be taken seriously. These are elements of satire in Voltaire’s philosophical tale, or conte philosophique (a literary recasting of debate), in which the author set out to persuade his readers that one of the central and dominant ideas of the 18th century was both false and dangerous. Known as philosophical optimism, this is the idea that everything that happens in life is for the best, even if we cannot understand why it is so.

On its first publication, in 1759, Candide was a sensation — banned, pirated, and talked about all over Europe. Seventeen editions appeared in the first year alone. Although it was disparaged in the 19th century by the leading writers of French

Romanticism, Candide has become a staple in the canon of Western literature. It has been reprinted continuously for more

than two centuries in all the major languages of the world and illustrated by artists of note. Candide as a cultural treasure has also been continuously transformed: imitated, excerpted, expanded, set to music, staged, and filmed. This adaptability was Candide’s specialty from the start: refashioning controversies has made it an engine for 250 years of debate.

Philosophical Contexts

Some of the most renowned thinkers and writers in Europe and England were proponents of philosophical optimism:

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the creator of the calculus, in Prussia; Alexander Pope in England; Jean-Jacques Rousseau in

France; and, for a long time, even Voltaire.

Leibniz’s highly influential Essais de Théodicée [Essays on Theodicy; 1710] argued that God’s benevolence is evident even in tragic events. Alexander Pope’s widely reprinted and translated poem, theEssay on Man (1725), set out to

“vindicate the ways of God to man,” and contains the thunderous line, “Whatever is, is right.” For many years, Voltaire himself was not immune to the seductive aspects of optimism and went so far as to translate Pope’s Essay into French

(1733) in order to give it wide readership on the Continent.

It was the horrific destruction of Lisbon by an earthquake on November 1, 1755, that shook Voltaire’s belief in philosophical optimism. Voltaire now rejected the idea that universally applicable, optimistic principles could explain such devastation. He first made this case within weeks in his Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne [Poem on the Lisbon

Earthquake]. Four years later, almost to the month, he brought forth Candideas a more fully elaborated attack on optimism.