Age

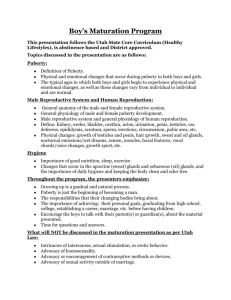

advertisement

Critical Period The Critical Period Hypothesis: • There is a biological period during which language can be acquired easily, perfectly, and without an accent; after this time, it is difficult, if not impossible, to learn language perfectly and without an accent. 1 Critical Period: First Language 1. Victor • feral child, France, 1799, 12 years old • no language, receptive to forest sounds • Dr. Jean Itard, 5 years tutoring; Victor learned “lait” and “O Dieu!” but never used them communicatively. • Itard, J. (1932). The wild boy of Aveyron. NY: Century. • “L’Enfant Sauvage” (“the Wild Child”), Francois Truffaut, 1970 2 Critical Period: First Language 2. Genie • 1970, California, 13.5 years old, isolated since 20 months (tied to bed by psychotic father), beaten if she vocalized, father spoke only in grunts. • After 5 years of education, she could speak, though slowly, and with greater-than-normal gaps between hearing and comprehension, overuse of formulaic language—recognizably different from native speakers. • Rymer, R. (1993). Genie: An abused child’s flight from silence. London: Michael Joseph. 3 Critical Period: First Language 3. Deaf Children • Born to hearing parents, sometimes “deprived” of exposure to sign language in infancy. • Newport, E. (1990). Maturational constraints on language learning. Cognitive Science ,14, 11– 28. • group 1: exposure since birth • group 2: exposure since school (age 4 – 6) • group 3: exposure after age 12. • Results showed decreasing grammaticality in ASL among the three groups. 4 Critical Period: Second Language 1. Patkowski, M. (1980). The sensitive period for the acquisition of syntax in a second language. Language Learning, 30, 449–472. • SL informants: group 1 began learning English before puberty; group 2 after puberty. • Speech recorded, transcribed, rated by native speakers on a scale from 0 (no knowledge of English) to 5 (educated native speaker). • note that this eliminates the phonological variable (i.e., accent). 5 Critical Period: Second Language 1. Patkowski, M. (1980). The sensitive period for the acquisition of syntax in a second language. Language Learning, 30, 449–472. What does the irregular shape of the distribution mean? Nearly everyone rated like a native speaker; success in SLA is “inevitable” before puberty. 6 Critical Period: Second Language 1. Patkowski, M. (1980). The sensitive period for the acquisition of syntax in a second language. Language Learning, 30, 449–472. What does the normal shape of the distribution mean? Results vary widely; some do well, others do not; success is not inevitable after the puberty. 7 Critical Period: Second Language 2. Johnson, J. & Newport, E. (1989). Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognitive Psychology, 21, 60–99. • Chinese and Korean subjects with varying ages of arrival in the United States; all highly educated (students and professors at universities). • Grammaticality judgment test – wide range of morphology / syntax rules, multiple sentences, some correct, some incorrect. Subjects make judgments about correctness. 8 Critical Period: Second Language 2. Johnson, J. & Newport, E. (1989). Critical period effects in second language learning. Cognitive Psychology, 21, 60–99. What does r = -0.87 mean? What does this correlation suggest? A pattern re: success in SLA (linearity), even before puberty. 9 Critical Period: Second Language 2. Johnson, J. & Newport, E. (1989). Critical period effects in second language learning. Cognitive Psychology, 21, 60–99. What does r = 0.16 mean? What does lack of correlation suggest? Learners have widely varying degrees of success in SLA 10 after puberty. Critical Period: Second Language 3. DeKeyser, R. (2000). The robustness of critical period effects in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 22, 499–533. • This study builds on and extends Johnson and Newport (1989), both methodologically and conceptually. 11 Critical Period: DeKeyser (2000) Questions for groups 1. What variable does DeKeyser add to J&N, and how is it measured? 2. Why does DeKeyser add the variable? 3. How does DeKeyser modify J&N’s instrument for data collection, and why? 4. What changes does DeKeyser make in the group from which data is collected, and why? 5. How are DeKeyser’s age-related results similar to, and different from, J&N’s (Question #1)? 6. What does the addition of the variable (point 2) allow him to explain relative to Question # 2? 12 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 1. What variable does DeKeyser add to J&N, and how is it measured? • Aptitude, or “analytic verbal ability” (p. 506). Measured by the Modern Language Aptitude Test. Participants completed the MLAT test (20, 5-way, multiple-choice questions) after the other instrument and the background questionnaire. 13 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 2. Why does DeKeyser add the variable? • In an effort to explain the “exceptions” in previous studies and observations – people or participants who are very successful with language learning, but began the process of language learning as adults. • Exceptions may explain the “right tail” in Patkowski’s distribution … 14 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 2. Why does DeKeyser add the variable? • In an effort to explain the “exceptions” in previous studies and observations – people or participants who are very successful with language learning, but began the process of language learning as adults. • Or the outliers in J&N … 15 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 2. Why does DeKeyser add the variable? • In an effort to explain the “exceptions” in previous studies and observations – people or participants who are very successful with language learning, but began the process of language learning as adults. • Or the “impressionistic data” in other studies (Coppieters, 1987) or the “partial overlap of the native and nonnative distributions in Birdsong” (1992) (p. 507). 16 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 3. How does DeKeyser modify J&N’s instrument for data collection, and why? • Grammaticality judgment task instrument shortened from 276 to 200 items / sentences. Original test “may have been too long for the participants to concentrate on every item” (p. 502). 17 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 4. What changes does DeKeyser make in the group from which data is collected, and why? • Native speakers of Hungarian, in and around Pittsburgh • Long period of residence (10+ years), to eliminate possible confusion between age of arrival and age of test taking in J&N, where period of residence was only minimum of 5 years. • Wide range in age of arrival and socioeconomic status. Why socioeconomic status? “a first approximation of verbal ability [i.e., aptitude]” (p. 508). 18 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 5. How are DeKeyser’s results similar to, and different from, J&N’s results (Question #1)? R = -0.63 19 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 5. How are DeKeyser’s results similar to J&N’s? The correlation between age of arrival and test score is remarkably similar. What does this suggest? An age-related effect in SLA. r = -0.77 r = -0.63 20 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 5. How are DeKeyser’s results different than J&N? Whereas J&N found a strong correlation between age of arrival and test score before puberty (r = -0.87), DeKeyser did not (r = -0.26). What does this suggest? J&N; r = -0.87 DeKeyser; r = -0.26 21 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 5. How are DeKeyser’s results different than J&N? • It might betray a lack of disruption in English proficiency between early and later arrivals; the uninterrupted downward linear trend might fail to illustrate the end of Critical Period. J&N; r = -0.87 DeKeyser; r = -0.26 22 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 5. How are DeKeyser’s results different than J&N? • Or, it might illustrate the different shapes of the distribution before and after puberty – which, while different from J&N, nevertheless suggest a disruption signaling the end of the CP. J&N; r = -0.87 DeKeyser; r = -0.26 23 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 5. How are DeKeyser’s results different than J&N? • On the other hand, DeKeyser’s results did show a difference between early and late arrivals relative to aptitude. • Early arrivals showed no correlation between English proficiency and aptitude (r = 0.07, ns). • Late arrivals showed a moderate correlation (r = 0.33; p < .05). • What does this mean? • That early arrivals did not need above average aptitude to achieve high English proficiency. Something else facilitated their success, maybe Critical Period effects. 24 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions 6. What does the addition of the aptitude variable allow him to explain relative to Question # 2? The “exceptions” to CP predications – i.e., adult learners who achieve very high levels of SL proficiency. 25 Critical Period: DeKeyser Questions “Among [those] who started acquiring English after age 16 but obtained a high score on the … test (over 175), all but one had an aptitude score of 6 or above” (p. 514). “Only the adults with above average aptitude eventually became near native” (p. 515). 26 Critical Period: Explanations 1. Neurological Explanation • Brain lateralization refers to the separation of brain functions into right and left. Language is controlled by the logical / analytical left side. • Lateralization is completed at around the time of puberty. Before lateralization, the brain is “plastic,” meaning that it is still developing and dynamic, and that brain functions and paths are not yet firm. • Some researchers have suggested that lateralization constrains the ability to learn language – that it constitutes the close of the Critical Period. 27 Critical Period: Explanations 2. Cognitive Explanation • Cf. Piaget’s theory of child development. Children advance from the Concrete operational stage (ages 7 to 11), wherein they begin to think logically about concrete events, to the Formal operational stage (age 11 ff.) wherein they develop abstract reasoning ability. • Researchers have suggested that there is a relationship between Piaget’s concrete and formal stages and the ability to learn language. Gaining the ability to think abstractly, which of course means we approach tasks like language learning differently, the Critical Period closes. 28 Critical Period: Explanations 3. Psychomotor Explanation • The Critical Period may be related to our physical development. More specifically, it may close with when we have completed the process of learning how to form the sounds of our native language. • African clicks? 29 Critical Period: Explanations 4. Affective Explanation • At a certain point in their development, children become conscious of themselves relative to other people. This consciousness affects their confidence, degree of extro / introversion, attitudes, inhibitions, and other affective aspects (i.e., emotions and feelings). • Researchers relate the CP to this development of affective consciousness. Before it, children are open and uninhibited, and they learn language easily and perfectly. After it – after the CP closes – their emotions inhibit language learning and render the result imperfect. 30 Critical Period: Explanations 5. Socio-Biological Explanation • Some scholars suggest a relationship between the process of sexual maturation and our ability to learn language. • At the point of sexual maturation (puberty), we lose the ability to learn a new language without an accent. The accent that we do acquire “marks” us for potential mates, making us un/ attractive to them, thereby maintaining the purity of the gene pool for future generations. • think hominids, race / ethnicity, social class … http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_vF9g37FCmk&feature=autop lay&list=PL037415A3348CAFC5&lf=results_main&playnext=2 31 Critical Period: Hakuta, Bialystok, & Wiley Recall how DeKeyser’s results differed from J&N’s. The uninterrupted downward linear trend perhaps failed to illustrate the end of CP. If the CP does not end, then is there such a thing as a critical period? This is exactly what Hakuta et al. wonder. J&N; r = -0.87 DeKeyser; r = -0.26 32