Lecture # 9

advertisement

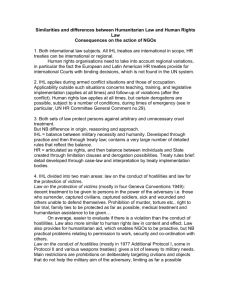

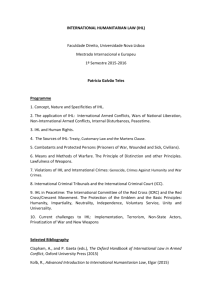

Human Rights Law and Related Regimes HUMR5140 Thursday 9th October 2014 Joanna Nicholson Fragmentation of International Law • Concern that international law (‘IL’) has developed in a fragmented way, leading to a lack of coherence between the different branches of international law (‘IL’) and the norms and institutions of the different branches of IL . • Human rights law (‘HRL’) overlaps with several other areas of IL, e.g. international humanitarian law, international criminal law, environmental law, refugee law. • What is the relationship between IHRL and international humanitarian law (‘IHL’) and international criminal law (‘ICL’)? E.g. Piracy Acts punishable under ICL E.g. crimes against humanity, genocide committed in peace time E.g. denial of freedom to practice religion in peace time detention. Breaches of International Human Rights Law War crimes against people and crimes against humanity and genocide committed during armed conflict. Breaches of IHL E.g. denial of freedom to practice religion during detention in breach of Additional Protocol II E.g. serious breaches of Hague Cultural Property Convention, 1954 E.g. minor breaches of Geneva Convention III or Hague Cultural Property Convention, 1954 Part I International Humanitarian Law What is IHL? • Also known as the Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC). • International law separates the question of when a state is lawfully entitled to use military force (jus ad bellum) from how hostilities are to be conducted once they are underway (jus in bello). Jus ad bellum • Concerns when states are lawfully entitled to use military force. • International law prohibits the use of force: - Article 2(4) Charter of the United Nations,1945 ‘All members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.’ • Exceptions: - Chapter VII, UN Charter Military sanctions authorised by the UN Security Council. - Article 51 UN Charter May resort to force only in the exercise of their inherent right of individual or collective self-defence. • Crime of aggression- Article 5(1)(d), ICC Statute 1998. Jus in bello • Governs how the conflict is conducted once it is underway. • This is IHL. • Aims to contain the violence. • Applies equally to all parties to a conflict. • It is concerned with: - The protection of civilians and civilian property. - The protection of those who fall into the hands of the enemy. - Means and methods of warfare. Roots of IHL dig deep into history….. • Many examples of rules of warfare from ancient societies. • Middle ages- rules of warfare as we know them today begin to develop. • Codification from mid-19th century onwards. - 1859, Battle of Solferino- Henry Dunant - 1864, Geneva Convention - 1863, Lieber Code • ‘Geneva Law’ and ‘Hague Law’ . Sources of IL Article 38, International Court of Justice Statute, 1945: • • • • International conventions. Customary law. General principles of law. Judicial decisions and teachings of highly qualified publicists. Sources of IHL Geneva Law (pertaining chiefly to protection) • Four Geneva Conventions, 1949 - GC I- Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field - GC II- Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked - GC III- Protection of Prisoners of War - GC IV- Protection of Civilians • Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions, 1977 - Applies primarily in international armed conflicts. • Additional Protocol II to the Geneva Conventions, 1977 - Applies in certain Non-international armed conflicts • Additional Protocols are concerned with both protection and means of warfare. Hague Law (pertaining chiefly to means of warfare) • • • • • • St. Petersburg Declaration, 1868 Hague Regulations, 1899, and 1907 Geneva Gas Protocol, 1925 Hague Convention on Cultural Property, 1954 Biological Weapons, 1972 Conventional Weapons Convention and Additional Protocols, 1980 • Chemical Weapons Convention, 1993 • Mine Ban Treaty, 1997 • Cluster Munitions, 2008 Customary International Law • International Committee of the Red Cross, customary international law study. - First published in 2005 - 161 Rules - discusses state practice - Available at: - https://www.icrc.org/customaryihl/eng/docs/v1 When does IHL Apply? • • • • • - There must be an armed conflict ‘an armed conflict exists whenever there is a resort to armed force between states or protracted armed violence between governmental authorities and organised armed violence between such groups within a state.’ Tadić, Decision on the Defence Motion on Jurisdiction, IT-94-1, 2, 1995, para 70 does not apply in internal disturbances, riots, sporadic violence IHL distinguishes between two different kinds of armed conflict: international armed conflicts (IAC) and non-international armed conflicts (NIAC). IACs- see Common article 2 GC and Article 1(3) and (4) Additional Protocol I. NIACs – see Common article 3, GC and Article 1, Additional Protocol II. The classification of the conflict as an IAC or a NIAC affects which laws that applies. However, it can be a complicated question to determine whether a conflict is an IAC or a NIAC. Majority of treaty law relates to IACs, but many of the same rules apply in NIACs as a matter of customary law. Tadić Jurisdictional Decision, para 94. Who does IHL apply to? • States • Non state armed groups • Individuals The Fundamental principles of IHL • • • • Distinction Military Necessity Proportionality Prohibition against superfluous injury and unnecessary suffering Distinction • Distinction (Art. 48 and 52(2), AP I) - All belligerents must distinguish between legitimate military objectives and civilian objectives and between combatants and civilians. - Military operations can be directed against military objectives and combatants only. Military Necessity • Parties to a conflict are permitted to apply any amount and kind of force to compel their enemy to submit- parties can do what is necessary to win the war. • BUT the principle of military necessity must be balanced against the principles of proportionality and unnecessary suffering. • Also it only covers measures which are lawful under IHL. • E.g. see Article 23(g), Hague Regulations, 1907. Military Necessity in the Lieber Code: • Military necessity admits of all direct destruction of life or limb of armed enemies, and of other persons whose destruction is incidentally ' unavoidable ' ….it allows of the capturing of every armed enemy, and every enemy of importance to the hostile government…’. (Article 15) • Military necessity does not admit of cruelty -- that is, the infliction of suffering for the sake of suffering or for revenge, nor of maiming or wounding except in fight, nor of torture to extort confessions. It does not admit of the use of poison in any way, nor of the wanton devastation of a district. It admits of deception, but disclaims acts of perfidy; and, in general, military necessity does not include any act of hostility which makes the return to peace unnecessarily difficult. (article 16) Proportionality • Attacks are prohibited if they will cause incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians, damage to civilian objects which would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated. (Article 51(5)(b) and 57(2)(b), Additional Protocol I). • Military commanders must consider the results of an attack as compared to the military advantage they will gain from carrying it out. • They must take precautions to ensure that the objective to be attacked is a military one and the damaged caused to civilians and civilian property is not disproportionate. Superfluous Injury and unnecessary suffering • St Petersburg Declaration, 1868. ‘Considering: That the progress of civilization should have the effect of alleviating as much as possible the calamities of war; That the only legitimate object which States should endeavour to accomplish during war is to weaken the military forces of the enemy; That for this purpose it is sufficient to disable the greatest possible number of men; That this object would be exceeded by the employment of arms which uselessly aggravate the sufferings of disabled men, or render their death inevitable; That the employment of such arms would, therefore, be contrary to the laws of humanity’. • Article 35(2), Additional Protocol I ‘It is prohibited to employ weapons, projectiles and material and methods of warfare of a nature to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering.’ ICRC – Rules of war (in a Nutshell) 22nd August 2014 https://www.icrc.org/en/document/rules-warnutshell#.VBqzS0t97wI Scenario A football match is taking place in a car park surrounded by buildings. About a third of the players and spectators are off-duty, unarmed soldiers. The rest- about 200 people- are civilians. Two shells are launched by the opposing side. Both hit the car park, killing and injuring many of those present. What questions would you need to ask in order to ascertain whether or not this was a lawful attack? Relationship between IHL and IHRL • Traditionally viewed as being separateseparate historical and philosophical origins; different objectives; different ethos. • Now widely agreed that IHRL can apply during armed conflict. IHL and IHRL IHL IHRL Applies During armed conflict During peacetime and armed conflict Duty bearers States Armed groups Individuals States Rights holders States Individuals Individuals States Remedies and ICJ Monitoring mechanisms Specific treaty regimes International criminal tribunals National courts ICJ International human rights bodies National courts Application of IHRL during armed conflict • Some rights can be limited (e.g. Articles 8, 9, 10 and 11 ECHR). Must be: - Prescribed by law - Necessary in a democratic society - In the interests of national security, territorial integrity or public safety. - For the protection of public order, health or morals - For the protection of the rights and freedoms of others. • Some rights can be derogated from during time of war or other public emergency (Article 15 ECHR) - Some rights cannot be derogated from: Article 2 (except for deaths resulting from lawful acts of war); Articles 3, 4 (paragraph 1) and 7. Possible scenarios during armed conflict: • Both IHL and IHRL apply in a particular situation and result in the same outcome. • Both IHL and IHRL apply in a particular situation and result in a different outcome. • Only IHL governs a situation, while IHRL is silent. • Only IHRL governs a situation while IHL is silent. What if there is a conflict between an IHL and IHRL norm? • Although application of IHL and IHRL will often lead to the same result, there are instances where there are important differences, e.g. viewing the deaths or injury of civilians being ‘collateral damage’, holding combatants as prisoners of war. • How are differences to be resolved: • Lex specialis principle: - The rule most specific to the situation is to be preferred. - Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, Advisory Opinion, ICJ Reports, 1996 para 25. - Legal Consequences of the Construction of a wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion, ICJ Reports, 2004, para. 106. Palestinian Wall, Advisory Opinion, para. 106 ‘the Court considers that the protection offered by human rights conventions does not cease in case of armed conflict, save through the effect of provisions for derogation of the kind to be found in Article 4 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. As regards the relationship between international humanitarian law and human rights law, there are thus three possible situations: some rights may be exclusively matters of international humanitarian law; others may be exclusively matters of human rights law; yet others may be matters of both these branches of international law. In order to answer the question put to it, the Court will have to take into consideration both these branches of international law, namely human rights law and, as lex specialis, international humanitarian law. ‘ However….. • Not everyone agrees with the lex specialis theory. • Other approaches include: - Complementarity- the two regimes complement and mutually reinforce each other. - Most favourable protection of victims- the regime which gives most protection to individuals should prevail. Some other debates: • Extra territorial application of ECHR • Capture or kill debate • IHRL obligations of non state actors Extra-territorial application of ECHR • Article 1 ECHR- ‘The High Contracting Parties shall secure to everyone within their jurisdiction the rights and freedoms defined in Section 1 of this Convention.’ • What does ‘within their jurisdiction’ mean? • ECtHR- jurisdiction not necessarily geographically limited - Loizidou v Turkey (1996)- state possesses jurisdiction when it has effective overall control of an area. - Bankovic (2001)- individuals killed outside an area under the effective overall control of a state by missiles or bombs fired from an aircraft were not within the state’s jurisdiction. - Al Skeini (2012) Capture or Kill? • In a NIAC, does IHRL place authorities under a duty to arrest a member of an armed group if possible, rather than kill them? IHRL and non State Actors • To what extent do human rights obligations bind non state actors? - They are not party to HR treaties. - Growing trend towards requiring non state actors with de facto authority over persons and/or territory to abide by HR norms. Suggested additional reading: • Kolb and Gaggioli, Research Handbook on Human Rights and Humanitarian Law, Edward Elgar Publishing, (2014). • Theodor Meron, The Humanization of International Humanitarian Law, Vol. 94(2) American Journal of International Law, 239-278 (2000). • Sassoli and Olsen, The relationship between international humanitarian law and human rights law where it matters: admissible killing and internment of fighters in non-international armed conflicts, Vol. 90 Number 871 International Review of the Red Cross (2008). Part 2 International Criminal Law What is ICL? • A body of international rules designed both to proscribe certain categories of conduct, and to make those who engage in such conduct criminally liable. • Comprises of: - substantive law- the rules which stipulate what behaviour constitutes an international crime and the elements that must be proved in order for a person to be convicted of an international crime. procedural law- the rules which determine how the various international criminal courts and tribunals function. Historical Background • Largely a product of the Twentieth century. • Post World War I- Leipzig trials of alleged German war criminals. - A German court trying its own nationals • Post World War II- International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg and International Military Tribunal of the Far East. Recent times • International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, 1993 (‘ICTY’) • International Tribunal for Rwanda, 1994 (‘ICTR’) • International Criminal Court, 2002 (ICC Statute, 1998) (‘ICC’) • Special Court for Sierra Leone, 2002 • Special Tribunal for Lebanon, 2009 • Extraordinary Courts for Cambodia (Agreement 2003) • The courts have different origins - The ICC was created by a treaty (ICC Statute) - ICTY and ICTR were created by UN SC Resolutions. - Hybrid courts- SCSL and ECCC- contain both domestic and international elements. • The jurisdiction of these courts depends upon the terms of their statutes which stipulate: - The crimes over which they have jurisdiction. - The geographical area which they have jurisdiction over, e.g. Rwanda, former Yugoslavia. - The time period over which they have jurisdiction. The core international crimes • • • • War Crimes Crimes against Humanity Genocide Crimes of Aggression War Crimes • War crimes are serious violations of IHL. In order to constitute a war crime: 1. The rule must constitute an infringement of IHL. 2. The rule must be part of customary international law or treaty law. 3.The violation must be serious: it must protect important values and involve grave consequences for the victim. 4. The violation must entail individual criminal responsibility for the accused under customary or treaty law. Tadić, Decision on the Defence Motion on Jurisdiction, IT-94-1, 2 October 1995, para 94. Examples of war crimes: 1. 2. 3. 4. Crimes against persons e.g. wilful killing/murder; torture; rape; inhuman or cruel treatment; slavery; hostage taking; enlistment/conscription or use of child soldiers. Crimes against property, e.g. pillage. Prohibited methods of warfare, e.g. intentionally attacking civilians or civilian objects; attacking or bombarding undefended towns and villages, improper use of insignia. Prohibited means of warfare, e.g. use of poison; use of asphyxiating gases. • See for example: Article 8, ICC Statute. N.B: Article 8 is not an exhaustive list, nor does it reflect customary international law. Crimes against Humanity • Developed in the wake of World War II. • Originally needed to be connected to an armed conflict, but this is no longer a requirement. • They are now viewed as a way of prosecuting serious violations of human rights. • In order to constitute a crime against humanity, there must be: - a widespread or systematic attack- not an isolated incident. - committed against a civilian population. Specific acts of Crimes against Humanity • For example: murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation/forcible transfer, torture, rape/sexual slavery/forced pregnancy, persecution against any identifiable group on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender grounds. • See: Article 7, ICC Statute. Genocide • Has a special intent requirement: to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group. • - Conduct amounting to genocide: Killing members of the group Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part. - Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group. - Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. • Article 6, ICC Statute. Crime of Aggression • Listed as one of the core crimes in Article 5 of the ICC Statute. • There was initially no definition given of the crime, but in 2010, an ICC Review conference agreed upon a definition: ‘the planning, preparation initiation or execution by a person in a position effectively to exercise control over or to direct the political or military action of a State, of an act of aggression which, by its character, gravity and scale constitutes a manifest violation of the Charter of the United Nations.’ • The ICC has no jurisdiction over the crime at present. A decision will be made by State parties regarding activating the provision in 2017. ICL and IHRL • Crimes against humanity and genocide- the criminalisation of serious violations of human rights. • Have been instances when ICTY has had recourse to HRL when defining crimes: - e.g. the crime of torture Additional Reading • Antonio Cassese and Gaeta, Cassese’s International Criminal Law, Oxford Uni Press, 2013. • William Schabas, Criminal Responsibility for Violations of Human Rights in Symonides (ed.), Human Rights, International Protection; monitoring and Enforcement, Aldgate, (2003). • Robert Cryer, The Interplay of Human Rights and Humanitarian Law: The Approach of the ICTY, Journal of Law and Security (2010) Vo. 14, No. 3, 511-527. • International Law Blogs: Opinio Juris; International Law Observer; EJIL: Talk.