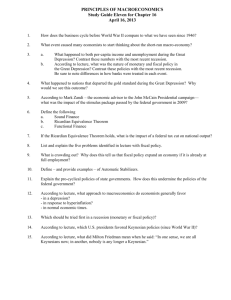

Non-Keynesian effects of fiscal policy

advertisement

Non linear effects of fiscal policy. The case of New Member States. Joanna Siwinska-Gorzelak Faculty of Economic Sciences University of Warsaw Objective • The main goal of the paper is to assess the short run effects of discretionary fiscal policy in New Member States (NMS) and examine the factors that may lead to “non-Keynesian” in these countries. • Up to now, NMS have been largely excluded from the analysis of non-Keynesian effects. Private consumption and fiscal policy • The standard Keynesian or “conventional” view of fiscal policy holds that in the short run fiscal adjustments (expansions) reduce (stimulate) disposable income, consumption and aggregate demand and due to sticky wages, prices or other misperceptions these shifts in demand affect the factors of production and output. • According to permanent income life cycle hypothesis (PILCH) and its generalization – the Ricardo – Barro Equivalence Theorem holds that the level of aggregate demand is unaffected by the tax/debt mix or by permanent changes in government spending – the former leaves consumption decisions unaffected, while the latter crowds it out; fiscal policy is thus ineffective in stimulating or dampening output, at least in the short-run. Non-Keynesian effects of fiscal policy • Giavazzi and Pagano (1990) analyzed the cases of Denmark and Ireland and concluded that these were “…the two most striking cases of “expansionary (fiscal) stabilizations in Europe”. • Since then, it has been well documented, that fiscal policy can have “non-Keynesian” effects i.e. that fiscal expansion can cause a recession and fiscal retrenchments an expansion in economic activity. • These effects do not fit into Keynesian nor Ricardian tradition Non-Keynesian effects of fiscal policy • The models by Blanchard (1990), Bertola and Drazen (1993), Sutherland (1997) and Perotti (1999) emphasize the demand side of non-Keynesian effects. • The models are neoclassical (i.e. based on PILCH) and each holds that expectations of future fiscal policy changes can give rise to nonlinear consumer behavior. • Theoretical (and empirical) literature suggests that the nonKeynesian effects stemming from the demand side, may be triggered by different set of factors than the non-Keynesian effects operating through the supply side. • For the former the crucial features of fiscal policy are the ones, that influence agent’s expectations of future policy changes, such as initial fiscal conditions (the level of debt and deficit, the level of expenditures) or size of fiscal adjustment; for the latter much more important is the composition of fiscal policy change. Blanchard’s (1990) model • Blanchard’s (1990) assumes a critical level of taxation t*, such that distortions caused by taxes, which exceed this level, imply a decrease in output. Consequently, there is also an associated critical level of debt d* that implies, through the government budget constraint, a future tax rate above the critical level t* and a lower output. • If consumers anticipate that this critical level of debt d* will be reached, then a fiscal consolidation that stabilizes or lowers debt value, allows o escape from the highly distortionary tax rate. Thus expected permanent income is higher and consumption rises. To put it in other words: today’s tax increase, which is does not exceed the critical value t* allows avoiding a larger future increase that would exceed t* and hence lower output. As a result, fiscal consolidation in “bad fiscal times” can be good news and raise consumption. • Blanchard notes, that if consumers have a constant probability of death (are not Ricardian), then “in normal times” i.e. when the economy is far from the critical debt level, despite a neoclassical structure, fiscal policy will have Keynesian effects. The model thus shows, that consumers behave in a nonlinear fashion – in “normal times” they behave in a Keynesian way (provided they have finite horizont), in “bad times” their behavior is reversed, what gives rise to non-Keynesian effects. Sutherland’s (1997) model • The government implements restrictive fiscal policy, in form of a large tax hike, when public debt reaches critical levels. • At low values of debt the probability of fiscal contraction is very low, thus a fiscal transfer from the government to households produces a Keynesian effect, as the probability that the future necessary increase in taxes will fall on the current consumer is low. • The higher is the debt value, i.e. the closer it is to the trigger point of fiscal stabilization, then a further increase in fiscal deficit causes consumption to fall, as consumers know that there is a high probability that the stabilization – a large tax increase - will take place during their lives and that the future income loss will be much higher than today’s government transfer. • Again, non-linear consumer behavior gives rise to non-Keynesian effects. This effect diminishes, when consumers have infinite lives in that case the results are Ricardian. Perotti’s (1999) model • Consumers; one group - rational and forward looking (PILCH), while the other group is either liquidity constrained or myopic, so that the consumption function of the latter group is purely Keynesian. • Increase in government expenditure stimulates pre-tax income, while taxes dampen it. The distortions caused by taxes increase in a non-linear fashion, as taxes enter the output function raised to the second power. Because policymakers do not smooth taxes out, future taxes are expected to be larger than today’s. • The non-Keynesian effects of fiscal policy emerge when the unexpected change in public spending or taxes changes the expectations about future disposable income (mainly through altering of the future tax path) of rational, unconstrained consumers. • Note, that the “Keynesian” consumers have a constant propensity to consume out of current income, and the bigger their proportion in the society, the less likely it is for the non-Keynesian effects to appear. • The “PILCH” consumers do not react to expected changes in fiscal policy. Consumption only changes when fiscal policy is unexpected. Perotti’s (1999) model • An unexpected increase in public expenditure may exert positive or negative effect on the consumption of “PILCH” consumers depending on the strength of output stimulus as opposed to the negative effect of the implied (future) tax increase. • If output stimulus outweighs tax distortions, consumption will increase as a result of government spending shock, if the opposite is true, consumption will decrease. • Therefore an increase in government spending may have perverse demand effects, provided that the share of PILCH consumers is not too low and that the effect of (expected) tax distortions outweighs the positive effects of spending. • The latter effect is more likely when the present discounted value of financing needs of the government is large – for instance when the government is struggling with a mounting debt. • Similarly the effect of tax increase may have different effects depending on the expected path of future taxation. An unexpected tax increase today may stimulate consumption of forward looking, unconstrained individuals, as it implies significantly lower tax distortions in the future. • Again, the emergence of non-Keynesian consumers’ reaction depends on the share of unconstrained consumers and on the present discounted value of financing needs of government. In “bad fiscal times” the PDV of financing needs of government is large, so today’s tax increase implies a significant decrease in future distortions. Perotti’s (1999) model • The model by Perotti (1999) holds that when the PDV of future government financing needs is low, fiscal policy will exert the usual Keynesian effects due to the reaction of liquidity constrained consumers PILCH consumers (provided that the fiscal action is has been unexpected). • When however the PDV of financing needs is high, it is possible that the unexpected fiscal policy will have perverse effects, because the PILCH consumers expect a future perverse change in income. Keynesian and non-Keynesian episodes of fiscal policy in OECD countries in years 1976-2001. • As a measure of the output effects of fiscal policy change, I use the concept of “corrected growth” developed by Cour et. al (1996). • Corrected growth of country i equals the actual growth of country i minus the actual growth in G7 countries and minus the difference between the potential growth rates between country i and G7. • A “Keynesian” fiscal adjustment/expansion is an episode, during which the “corrected growth” is smaller/larger than in the preceding year. • An episode is “non-Keynesian” when fiscal adjustment/expansion is coupled with a “corrected growth” which is larger/smaller than in the preceding year. Keynesian and non-Keynesian episodes of fiscal policy in OECD countries in years 1976-2001 We isolated 40 fiscal expansions and 73 fiscal adjustments. Out of these 113 significant fiscal policy changes, 50 were non-Keynesian. Thus, a first conclusion emerges – non-Keynesian effects are not a random anomaly, they seem to be quite a frequent phenomenon. Keynesian Non- Keynesian Non-Keynesian expansions Keynesian adjustments adjustments expansions Number of episodes Average change of balance, in 23 46 27 -2,47 -2,62 2,24 2,53 1,58% -1,38 -1,72 1.01 the cyclically adjusted primary govt. 17 % of potential GDP. Average “adjusted growth” Source: own calculations, OECD database Empirics • The empirical literature on demand-side non-Keynesian effects, starting with the seminal contribution of Giavazzi and Pagano (1990) confirms (although not uniformly) the existence of non-Keynesian effects (or a somewhat weaker phenomenon – the non-linear effects) for OECD countries • The “trigger” factors: large fiscal imbalances (deficit and/or public debt) and or size of fiscal shock (large fiscal expansions and adjustments). Effects of a positive public expenditure shock • Constrained (myopic) consumers – Both positive and negative effects due to current influence of G on disposable income • Unconstrained (rational)consumers – Only unexpected shocks matter; expected shocks do not change the consumption path of PILCH consumers – Both positive and negative effect due to current effect on disposable income – Negative effect due to expected increase in future taxation – Both positive and negative effect due to future impact of the higher government spending on disposable output. • Depending in the magnitude of these offsetting effects, the impact of unexpected spending shock can be either positive or negative • The magnitude of the adverse effects of spending shocks can be amplified by large fiscal imbalances (expectations of a significant increase in future taxation), by adverse economic conditions (amplification of the adverse effect on disposable income) • Non- linearity does not necessarily imply a non-Keynesian output effect, as they may be too weak to offset the effects of fiscal policy. Effects of increased taxation • Constrained (myopic) consumers – Negative effects due to current influence of T on disposable income • Unconstrained (rational)consumers – Only unexpected shocks matter; expected shocks do not change the consumption path of rational consumers – Negative effect due to current decrease of disposable income – Positive effect due to future decrease in taxes and hence increase in expected (future) disposable income • Depending in the magnitude of these offsetting effects, the impact of unexpected spending shock can be either positive or negative Empirical strategy Estimate Euler equation of the form cit 1 yit 2 fiscit 3 ( fiscit dummy) t where: cit – log difference of real, private consumption (i.e. percentage change) yit – log difference of real, disposable household income fisc – cyclically adjusted fiscal impulse dummy variable that equals 1, when times are hard (public deficit is excessive or economy is in recession) Data source: OECD; 1970-2007. Regression results; OECD countries Income Deficit (1) 0.747*** (0.222) 0.775*** (0.0196) Deficit*dummy_def Deficit*dummy_gdp (2) 0.725*** (0.217) 0.794*** (0.0201) -0.160*** (0.0563) (3) 0.591*** (0.212) 0.809*** (0.0191) -0.152*** (0.0531) -0.656*** (0.116) Spend*dummy_gdp Constant Observations R-squared Number of countries Standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 -0.0174*** (0.00490) 504 0.7 18 -0.0123*** (0.00463) 504 0.7 18 (4) 0.666*** (0.219) 0.798*** (0.0198) -0.155*** (0.0554) -0.388*** (0.146) -0.0140*** (0.00481) 504 0.7 18 NMS • Included are 10 NMS: Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia • Years: 1992-2007 • AMECO database • Variables: – Private final consumption expenditure – Total current expenditure, excluding interest of general government – Gross national disposable income – Final consumption expenditure of general government – Total current revenue of general government – Current taxes on income and wealth Regression results; NMS Expected income Fiscal impulse Fiscal impulse*dum_def (1) FE 0.866*** (0.154) -0.0103 (0.0203) -0.117** (0.0522) (2) PW 0.903*** (0.155) -0.00439 (0.0119) -0.112* (0.0570) Exp*dum_gdp (3) FE 0.850*** (0.141) -0.00990 (0.0185) -0.0181 (0.0520) -0.260*** (0.0552) (4) PW 0.879*** (0.143) -0.00280 (0.0101) -0.0396 (0.0525) -0.240*** (0.0690) 0.00923 (0.00755) 118 10 0.388 0.00801 (0.00593) 118 10 0.446 Expenditure shock Exp*dum_def Constant Observations Number of countries R-squared Standard errors in parentheses *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 0.00782 (0.00827) 118 10 0.257 0.00451 (0.00496) 118 10 0.376 (5) FE 0.883*** (0.140) -0.194*** (0.0713) 0.00606 (0.0143) -0.129 (0.0784) 0.00876 (0.00749) 118 10 0.400 Conclusions • Fiscal policy has a non-linear impact on private consumption spending both in OECD and in New Member States • As usual, in case on NMS, the short time horizon and poorer data quality imply that any estimation results must be treated with considerable amount of skepticism • The non-linearity seems to be triggered by fiscal imbalances and by recessions • This implies that stabilizing the business cycle with discretionary fiscal policy can be difficult… References • Blanchard O., (1990) Comment on “Can severe fiscal contractions be expansionary?” NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1990, ed. by Blanchard O., and Fischer S., MIT Press • Cour P., Dubois E., Mahfous S., Pisani-Ferry J (1996) The cost of fiscal retrenchment revisited: How strong is the evidence? • Giavazzi F., Pagano M. (1990) Can Severe Fiscal Contractions Be Expansionary? Tales of Two Small European Countries. NBER Macroeconomics Annual • Perotti R., (1999) Fiscal policy in good times and bad. The Quarterly Journal of Economies, November • Sutherland A. (1997) Fiscal Crises and Aggregate Demand: Can High Public Debt Reverse the Effects of Fiscal Policy? Journal of Public Economics 65.