Learning Partnerships Model (PowerPoint)

advertisement

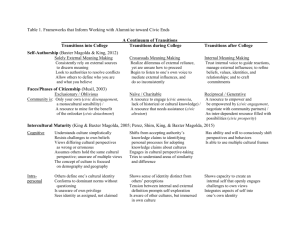

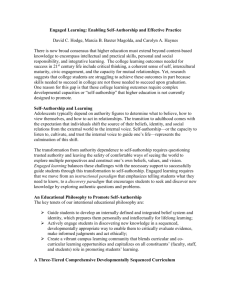

THE LEARNING PARTNERSHIPS MODEL FOR STUDENT OGANIZATIONS Adapted from Baxter Magolda, 2011 What is the Learning Partnerships Model? The Learning Partnerships Model is a framework that practitioners can use to promote self-authorship in student leaders. It is based on three assumptions (which provide a challenge to students' assumptions about the way the world works) and uses three principles (which offer support to help students learn). It claims to help students develop an internal belief system, an internal identity/sense of self, and a capacity for mutual, interdependent relationships (Baxter Magolda, 2011). Three assumptions: Knowledge is complex and socially constructed One’s identity plays a central role in crafting knowledge claims Knowledge is mutually constructed via the sharing of expertise and authority Three principles: Validate student leaders capacity to know Situate learning in student leaders experiences Define learning as mutually constructing meaning Results: An internal belief system, an internal identity/sense of self, and a capacity for mutual, interdependent relationships How do I implement the Learning Partnerships Model? The Learning Partnerships Model is based on three principles and three assumptions. Below is a summary of how the LPM was implemented in an academic advising program, and these same principles can be applied in your one-on-one meetings with student leaders as well. An Example of a Program based on the LPM The STEP program [an academic advising program focusing on retention of students who were struggling academically] provided regular one-on-one sessions with a professional advisor. Session frequency varied by student and was based on student needs, with most students attending formal sessions every three weeks. The STEP curriculum was flexible in that it could be tailored to individual student needs, and it included topics such as goal setting, time management, study skills, and career exploration. In addition to teaching students specific academic success skills, advisors also can purposefully work on helping students develop skills for how they made sense of situations, made planful decisions, understood themselves, and balanced competing expectations of them from important others (e.g., organization, parents, peers). The following subsections describe how STEP functioned as a learning partnership. (This plan can be adapted towards developing partnership between organization advisors and student leaders). Validating Students' Capacity to Know STEP was designed with the assumption that knowledge is complex and socially constructed —assumption one of Baxter Magolda's (2001) three key assumptions of the LPM. Consequently there is not a suggestion that there was a formula for success. Instead advisors should approach students as important authorities. They should solicit students' ideas, rather than telling students how to modify their behaviors. By inviting students to construct their own plans for success, and by taking their contributions seriously, advisors can work to validate students' capacity to know. Situate Learning in Students' Experiences In addition to helping student leaders see themselves as capable learners, STEP was predicated on the notion that the self is central to knowledge construction— students' identities are important influences on how knowledge can and should be constructed and to what ends. Meetings should be planned around student leaders needs and focused on helping students identify who they were, who they wanted to be, and how to make plans based on these goals. Advisors should help students integrate identity goals and knowledge construction. Define Learning as Mutually Constructing Meaning As students work on individualized plans for success, and run into obstacles, the advisors should coach them but never tell them what to do. Advisors can demonstrate their expertise while also coaxing them to notice their own authority through their invitations to explore motivations behind their behaviors, making plans for future obstacles, considering how to transfer their skills into other situations, and reminders to incorporate particular behaviors, and reflections on progress. Through this work advisors can help student leaders see that they shared authority and expertise and that learning is about mutually constructing meaning. What can they expect along the way? Student leaders will likely move through a set of stages on the way to selfauthorship. Advisors may notice their views regarding authority, themselves, and others changing. Self-Authorship Becoming self-authored requires transformational learning that helps students "learn to negotiate and act on [their] own purposes, values, feelings, and meanings rather than those [they] have uncritically assimilated from others" (Mezirow 2000, 8). Self-authorship encompasses and integrates three dimensions of development: • epistemological, intrapersonal, and interpersonal (Kegan, 1994). • The epistemological dimension of development refers to how people use assumptions about the nature, limits, and certainty of knowledge to decide what to believe (Kitchener, 1983; Perry, 1970). • How people use assumptions about knowledge to craft beliefs is closely related to how they construct their identities, or the intrapersonal developmental dimension (Abes, Jones & McEwen, 2007; King & Baxter Magolda, 1996). • Self- authored persons have the ability to explore, reflect on, and internally choose enduring values to form their identities rather than doing so by simply assimilating expectations of external others (Kegan, 1994). They then use this internal identity to interpret and guide their experiences and actions. This internal identity that is not overly dependent on others is a crucial aspect of standing up for one’s own beliefs (an aspect of cognitive maturity). Similarly, it is a crucial aspect of mature relationships (the interpersonal dimension) that require respect for both self and other. Dimension External Formulas Crossroads Self-authorship Epistemological (How do I know what I know?) View knowledge as certain or partially certain, yielding reliance on authority as source of knowledge; lack of internal basis for evaluating knowledge claims results in externally defined beliefs View knowledge as contextual; develop an internal belief system via constructing, evaluating, & interpreting judgments in light of available evidence and frames of reference Intrapersonal (How do I understand myself?) Lack of awareness of own values and social identity, lack of coordination of components of identity, and need for others’ approval combine to yield an externally defined identity that is susceptible to changing external pressures Dependent relations with similar others are source of identity and needed affirmation; frame participation in relationships as doing what will gain others’ approval Evolving awareness & acceptance of uncertainty & multiple perspectives; shift from accepting authority’s knowledge claims to personal processes for adopting knowledge claims; recognize need to take responsibility for choosing beliefs Evolving awareness of own values and sense of identity distinct from external others’ perceptions; tension between emerging internal values and external pressures prompts self-exploration; recognize need to take responsibility for crafting own identity Evolving awareness of limitations of dependent relationships; recognize need to bring own identity into constructing independent relationships; struggle to reconstruct of extract self from dependent relationships Interpersonal (How do I understand others?) Choose own values & identity in crafting an internally generated sense of self that regulates interpretation of experience and choices Capacity to engage in authentic, interdependent relationships with diverse others in which self is not overshadowed by need for others’ approval, mutually negotiating relational needs; genuinely taking others’ perspectives into account without being consumed by them Baxter Magolda, 2011 How does the Guided Reflection Process fit into the Learning Partnerships Model? Advisors can use the principles of the Learning Partnerships Model in the implementation of the Guided Reflection Process (a form of experiential education, is a collaborative teaching and learning strategy designed to promote academic enhancement, personal growth, and civic engagement. Students render meaningful service in community settings that provide experiences related to academic material. Through guided reflection, students examine their experiences critically, thus enhancing the quality of both their learning and their service). By connecting with student leaders and helping them to create their own goals and paths, advisors allow students leaders to be “authors of their own experiences” and develop their own values and identity. Research has shown that the Learning Partnerships Model does move students on a path to self-authorship. While the Guided Reflection Process is not always easier than telling students directly what to do, it does help them grow and develop. It allows students to learn how to take others’ perspectives into account while still listening to their own inner voice. Our ultimate goal as professionals is the growth and development of students, and through this process we can help them prepare for the world they will experience when they leave college. Unfortunately, most traditional-age college students have not yet developed these capacities, both because many enter college having been socialized to uncritically accept knowledge from authorities (including well-intentioned advice), and because many influential people in students' lives are inclined to simply offer such knowledge. Summary The existence of peer groups and organizations is insufficient to ensure a sense of belonging. Helping students select groups that match their values yet challenge them to think differently can yield supportive environments in which to grow. Educators advising student organizations, class project groups, or residential units can guide leaders to use the process for articulating, analyzing, and refining perspectives. Supportive advisors respect and help students articulate their feelings and thoughts about their experiences, encourage reflection on the meaning of their experiences, and assist students in making their own interpretations of how to view themselves and relationships in light of their experiences. The key to support in developmentally effective experiences is to respect students’ current meaning making, encourage reflection and interpretation, and assist them in making their own sense of experiences (Baxter Magolda, 2004; King et al., 2009).