Here

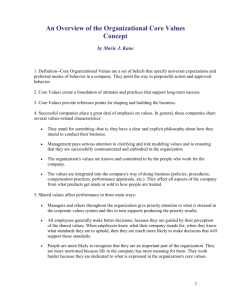

advertisement

Free Will Agenda • What is Free Will? The “Authorship Slogan” • Why think we don’t have it? The Evil Scientist Argument • The standard philosophical positions: Compatibilism, Incompatibilism, Libertarianism, and Hard Determinism. Our Question • Our question is, Do we have free will? I don’t understand. • What is “free will” supposed to be? What is a will? What sort of freedom is at issue? • I propose to table these questions until later. • … So let’s just change the subject. A Picture of Action The “Standard Picture” of Action: Whenever an agent acts, there are three distinct elements I want to…, I choose to…, I plan to... Cause 1. The psychological sources of the action Causes 2. The action itself 3. The consequences of the action Authorship of actions SLOGAN: We are the authors of our actions. This is a METAPHOR! Philosophers use these all the time, but they can mislead. Think: “What does the metaphor mean in literal terms?” Chasing down the parallel Authorship of books Explanation Responsibility Certain text & pictures appear in a book because those text & pictures are what the author chose, decided, etc., to include. The author is responsible for the content of the book. If there’s racism in there, she’s responsible. If there’s beauty or insight in there, she’s responsible. “Authorship” of actions You acted as you did because you chose, decided, etc., to do so. You are responsible for your actions. If it was cruel or wicked for you to do what you did, you’re responsible. If it was brave, you’re responsible. The Authorship slogan interpreted The Authorship Slogan: If an agent P performs an action A, then: 1) Any full explanation for why P performed A must include her choices, etc.; and 2) P bears responsibility for A. This will be my focus Free Will = Authorship • • • Proposal: replace “Do we have free will?” with “Are we ever the ‘authors’ of our actions?” This means we stop asking, “Do we have free will?” Instead we ask: 1. Are our choices, etc., ever part of the full explanation for why we perform our actions? 2. Are we ever responsible for an action we perform? If the answer to either question is ‘no’, then we will conclude: We don’t have free will. Agenda • What is Free Will? The “Authorship Slogan” • Why think we don’t have it? The Evil Scientist Argument • The standard philosophical positions: Compatibilism, Incompatibilism, Libertarianism, and Hard Determinism. The Evil Scientist Argument I want to show why there might be a problem for “authorship.” STRATEGY: (1) Propose a case in which it is utterly clear that the agent is not the “author” of his action. (2) Give reasons why we might think our situation is exactly similar. Meet Al and the Evil Scientist Evil Scientist Al The Evil Scientist Scenario I hereby choose to raise my arm! electrode in the brain + forced choice • Is Al the “author” of his action? Who cares about the Evil Scientist Scenario? • That’s too bad for Al, but what does this have to do with us? • Control by external forces: Al Addiction • Some people used to think that we are all in Al’s situation (and the addict’s, too): what we want is determined by external forces. Universal Determinism Definitions: a total state of the universe: a description of how things are that leaves no detail out, no matter how specific. Universal Determinism: The total state of the universe at a time t determines the total state of the universe at every time after t; it is impossible that the universe evolve in any other way. Determinism and the thin red line According to Universal Determinism: Where you can get depends only on where you start: Your life Your birth time The entire course of your life is determined by how things were a long time before you were born. green start red start The actual initial state of the universe The Evil Scientist Argument for Incompatibilism 1) Descriptive Premise: In the Evil Scientist Scenario, Al is not the “author” of his actions. In particular, Al is not responsible for what he does. 2) Analogy Premise: If Universal Determinism is true, our situation is exactly like Al’s in all relevant respects. Incompatibilism: If Universal Determinism is true, then we are never the “authors” of our actions. In particular, we are not responsible for what we do. Spinoza Said It Best Baruch Spinoza, Letter to G.H. Schaller (The Hague, October 1674) (trans. by R. Elwes): [E]very individual thing is necessarily determined by some external cause to exist and operate in a fixed and determinate manner. Further conceive, I beg, that a stone, while continuing in motion, should be capable of thinking and knowing, that it is endeavouring, as far as it can, to continue to move. Such a stone, being conscious merely of its own endeavour and not at all indifferent, would believe itself to be completely free, and would think that it continued in motion solely because of its own wish. This is that human freedom, which all boast that they possess, and which consists solely in the fact, that men are conscious of their own desire, but are ignorant of the causes whereby that desire has been determined Agenda • What is Free Will? The “Authorship Slogan” • Why think we don’t have it? The Evil Scientist Argument • The standard philosophical positions: Compatibilism, Incompatibilism, Libertarianism, and Hard Determinism. Compatibilism and Incompatibilism Compatibilism: “Authorship” of actions (i.e. “free will”) is compatible with Universal Determinism. Incompatibilism: If Universal Determinism is true, then we are never the “authors” of our actions. [Note: The argument just presented is an argument for Incompatibilism.] 2 Kinds of Incompatibilism Hard Determinism: Universal Determinism is true; so we do not have free will. Libertarianism: We have free will; so Universal Determinism is false. [Note: The Hard Determinist and the Libertarian agree about the incompatibility of Universal Determinism and “authorship”.] Summary of philosophical positions YES Universal Determinism and “authorship” compatible? Compatibilism NO YES “Authorship” ? NO Hard Determinism Libertarianism Hume’s Theory • David Hume (1711 - 1776) • Hume is a Compatibilist: he believed that we “author” our actions, despite the fact that everything is determined by circumstances that obtained before our birth. Hume’s View “[A]ll men have ever agreed in the doctrine both of necessity and of liberty, according to any reasonable sense.” (para. 3) • The Doctrine of Necessity: All human motives, decisions, and actions are determined (necessitated) by their causes. • The Doctrine of Liberty: All who are not physically restrained have liberty (i.e. “free will”). Agenda • Hume’s Positive Arguments: first articulate (and criticize) Hume’s arguments for his own views. • Hume’s Defense: then articulate (and criticize) Hume’s defense against the Evil Scientist Argument. Hume has two positive arguments Hume’s Positive Arguments: first articulate (and criticize) Hume’s arguments for his own views. 1. The argument for the Doctrine of Necessity. 2. The argument for the Doctrine of Liberty. Causation and Necessitation • Hume holds that the relation of cause-andeffect is necessitating. • Causes Necessitate: If an event C causes an event E, then it is impossible that C should have occurred, and E not. Hume’s Challenge: “Let any one define a cause, without comprehending, as a part of the definition, a necessary connexion with its effect … and I shall readily give up the whole controversy.” (para. 25) Hume: Causes Necessitate A possible situation? The actual situation effect effect 8 8 IMPOSSIBLE! cause Any possible situation in which C occurs must be a situation in which E also occurs. cause Human Actions and Decisions are Caused [A] prisoner, when conducted to the scaffold, foresees his death as certainly from the constancy and fidelity of his guards, as from the operation of the axe or wheel. His mind runs along a certain train of ideas: the refusal of the soldiers to consent to his escape; the action of the executioner; the separation of the head and body; bleeding; convulsive motions, and death. Here is a connected chain of natural causes and voluntary actions; but the mind feels no difference between them in passing from one link to another […] (para. 19) Human Actions and Decisions are Both Causes and Effects No Escaping! Causes Causes “the refusal of the soldiers to consent to his escape” “the action of the executioner” “the separation of the head and body;” (etc.) Hume’s Argument for the Doctrine of Necessity (1) Causes necessitate: if an event C causes an event E, then it is impossible that C should have occurred and E not (rather than some other event E*) (2) Actions are caused: Human motives, choices, actions, etc., have causes. (C) The Doctrine of Necessity: Human motives, choices, actions, etc., are determined (necessitated) by their causes. A Problem for Hume’s Argument So far, I’ve been explaining Hume’s argument for the Doctrine of Necessity. Now, I’ll switch sides, and explain why his argument may be wrong. Schrödinger’s Cat ? (50% chance) Indeterministic Causation: It seems that we cause Tibble’s death by putting him in the box. But that doesn’t determine that he will die. The Objection (1) Causes necessitate: if an event C causes an event Falseoccurred E, then it is impossible that C should have and E not (rather than some other event E*) (2) Actions are caused: Human motives, choices, actions, etc., have causes. (C) The Doctrine of Necessity: Human motives, choices, actions, etc., are determined (necessitated) by their causes. Hume has two positive arguments Hume’s Positive Arguments: first articulate (and criticize) Hume’s arguments for his own views. 1. The argument for the Doctrine of Necessity. 2. The argument for the Doctrine of Liberty. Hume’s Defense: then articulate (and criticize) Hume’s defense against the Evil Scientist Argument. Hume’s Argument II: The Principle of Liberty “By liberty, then, we can only mean a power of acting or not acting, according to the determinations of the will; this is, if we choose to remain at rest, we may; if we choose to move, we also may. Now this hypothetical liberty is universally allowed to belong to every one who is not a prisoner and in chains. Here, then, is no subject of dispute..” (para. 23) • The English Translation: Liberty is: being able to do what you want to do, and … being able to not do what you want not to do. The Argument (1) Liberty is the power to do (or not do) as we choose. (2) All who are not “a prisoner in chains” have that power. (C) All who are not “a prisoner in chains” have liberty. (para. 23) A Problem for Hume’s Argument • Hume’s claim that all of us who are not physically restrained can act or not as we choose is very plausible. • But is this what is at issue in the free will debates? • Note: Poor Al in the evil scientist scenario still has “liberty” in Hume’s sense. But we have found reason to doubt that he really “authors” his actions. • So: Hume has shown us a conclusion which is irrelevant to the free will debate. Agenda Hume’s Positive Arguments: first articulate (and criticize) Hume’s arguments for his own views. Hume’s Defense: then articulate Hume’s defense against the Evil Scientist Argument. Hume’s Version of the Evil Scientist Hume is speaking for his opponent: “[I]f voluntary actions be subjected to the same laws of necessity with the operations of matter, there is a continued chain of necessary causes, pre-ordained and pre-determined, reaching from the original cause of all to every single volition of every human creature. No contingency anywhere in the universe; no indifference; no liberty. While we act, we are, at the same time, acted upon. The ultimate Author of all our volitions is the Creator of the world, who first bestowed motion on this immense machine, and placed all beings in that particular position, whence every subsequent event, by an inevitable necessity, must result.” (para. 32) God is the Evil Scientist • Hume’s opponent concludes: God is responsible for all of our actions, and we are responsible for none of them. “For as a man, who fired a mine, is answerable for all the consequences whether the train he employed be long or short; so wherever a continued chain of necessary causes is fixed, that Being, either finite or infinite, who produces the first, is likewise the author of all the rest, and must both bear the blame and acquire the praise which belong to them.” (para. 32) • NOTE: Theological entanglement is entirely optional. Hume vs. the Evil Scientist Hume has two responses to his version of the Evil Scientist argument. The First Response: We are naturally inclined anyway to blame people for their bad actions (we thereby “hold them responsible”) “The mind of man is so formed by nature that, upon the appearance of certain characters, disposition, and actions, it immediately feels the sentiment of approbation or blame [….] A man who is robbed of a considerable sum; does he find his vexation for the loss anywise diminished by these sublime reflections? Why then should his moral resentment against the crime be supposed incompatible with them? […] Both these distinctions are founded in the natural sentiments of the human mind: And these sentiments are not to be controuled or altered by any philosophical theory or speculation whatsoever.” (para. 35) Hume vs. the Evil Scientist (Again) The Second Response: God and his attributes are a really big mystery anway, so we shouldn’t get too worked up about these theological matters. “These are mysteries, which mere natural and unassisted reason is very unfit to handle; and whatever system she embraces, she must find herself involved in inextricable difficulties, and even contradictions, at every step which she takes with regard to such subjects [….] [T]o defend absolute decrees, and yet free the Deity from being the author of sin, has been found hitherto to exceed all the power of philosophy. Happy, if she be thence sensible of her temerity, when she pries into these sublime mysteries; and leaving a scene so full of obscurities and perplexities, return, with suitable modesty, to her true and proper province, the examination of common life; where she will find difficulties enough to employ her enquiries, without launching into so boundless an ocean of doubt, uncertainty, and contradiction!” (para. 36) Against Natural Inclination • Hume’s first response seems to miss its mark. The question is not what we are naturally inclined to do; the question is whether it is legitimate to do what we are naturally inclined to do. • Suppose that we were naturally inclined to kill the loved ones of the people we hate. Does this fact about our natural inclinations make the killing legitimate? • Chimpanzees and Bonobos. • Is it true that we are naturally inclined to punish the guilty? Against Hume’s Dismissal of Theology • This is not a response. • Theological speculation is not essential to the Evil Scientist argument. Kane’s Theory • Robert Kane (1938 - ) • Kane is a Libertarian: he believes that we “author” our actions, partly because our decisions, choices, etc., are not determined by antecedent conditions. On to Kane: Our Agenda • Kane’s Evil Scientist: first identify Kane’s problem with the Evil Scientist. • Surface Freedom and Deeper Freedom: then review Kane’s explanation of free will in terms of what he calls “Deeper Freedom”. • Kane’s Defense: finally, show how Kane proposes to establish authorship. Kane’s Libertarianism • Kane is a Libertarian: he believes that we have “free will”, and so some of our actions are not determined. • As a Libertarian, Kane can accept the Evil Scientist Argument for Incompatibilism. • Kane’s evil scientist: Frasier of “Walden Two” • Kane still faces a variant of the Evil Scientist Argument. The Evil Scientist Without Universal Determinism I hereby choose to raise my arm! ? The problem isn’t that Al’s desire is determined; it’s that it’s caused. The Hard Problem of Free Will “While we act, we are, at the same time, acted upon.” I want to…, I choose to…, I plan to... Cause caused External Circumstances Psychological Sources of Action Action The Evil Scientist Argument against Authorship 1) Descriptive Premise: In the Evil Scientist Scenarios (±Universal Determinism), Al is not the “author” of his actions. In particular, Al is not responsible for what he does. 2) Analogy Premise: Our situation is exactly like Al’s in all relevant respects. (C) No Authorship: We are never the “authors” of our actions. In particular, we are not responsible for what we do. Agenda • Kane’s Evil Scientist: first identify Kane’s problem with the Evil Scientist. • Surface Freedom and Deeper Freedom: then review Kane’s explanation of free will in terms of what he calls “Deeper Freedom”. • Kane’s Defense: finally, show how Kane proposes to establish authorship. Surface Freedom vs. Deeper Freedom • Kane distinguishes between surface freedom and deeper freedom: “[Walden Two-ers] have maximal surface freedom of action and choice (they can choose or do anything they want), but they lack a deeper freedom of the will because their desires and purposes are created by their behavioral conditioners or controllers.” (p. 501, col. 1) • Surface Freedom: being able to do what you want. • Deeper Freedom: “freedom of the will” What is Deeper Freedom? A Simple Proposal • Surface Freedom: the ability to act according to what you want, choose, decide, etc. (All who are not “a prisoner in chains” have this, at least sometimes.) • Deeper Freedom: control over the shape of your own psychology: what you want, what matters to you, etc. Agenda • Kane’s Evil Scientist: first identify Kane’s problem with the Evil Scientist. • Surface Freedom and Deeper Freedom: then review Kane’s explanation of free will in terms of what he calls “Deeper Freedom”. • Kane’s Defense: finally, show how Kane proposes to establish authorship. Kane’s Defense: Agenda • Kane’s 2-Prong Strategy: Kane attempts to establish that we have authorship in two very different ways. • Self-Forming Actions (SFAs): The key concept in Kane’s argument. • Kane’s Unstated Argument: Kane’s arguments that we are responsible for our actions. Kane’s 2 Prong Strategy I: Two Kinds of Action SFA’s (Self-Forming Actions) APA’s (Auto-Pilot Actions) Are NOT determined Are determined (by character, habits, standing motives, etc.) Do NOT help form our character, habits, standing motives, etc. Help form our character, habits, standing motives, etc. Kane’s 2 Prong Strategy II: Passing the Buck Kane needs to do two things: Secure “authorship” for APA’s; and secure “authorship” for SFA’s. For APA’s: Pass the buck to SFA’s. We are responsible for our APA’s because we are responsible for our character. For SFA’s: ???? Kane’s 2 Prong Strategy III: Aristotle’s Dictum How come Kane thinks he can pass the buck from APA’s to SFA’s? Because he holds Aristotle’s Dictum: An agent is responsible for an action that was determined by her character, habits, etc., (together with circumstances) only if she is responsible for her character, habits, etc. “[I]f a man is responsible for the wicked acts that flow from his character, he must at one time in the past have been responsible for forming the character from which those acts flow.” (p. 503, col. 2, bottom) Kane’s Defense: Agenda • Kane’s 2-Prong Strategy: Kane attempts to establish that we have “Deeper Freedom” in two very different ways. • Self-Forming Actions (SFAs): The key concept in Kane’s argument. • Kane’s Unstated Argument: Kane’s arguments that we are responsible for our actions. SFA’s: The Definition Definition: An SFA (“self-forming action”) is an action or choice which contributes to the formation of one’s character. “Not all choices or acts done ‘of our own free wills’ have to be undetermined, but only those choices or acts in our lifetimes by which we made ourselves into the kinds of persons we are. Let us call these ‘self-forming choices or actions’ or SFAs.” (pp. 503-504) SFA’s: Examples Examples: (For each of these identify: the SFA, and the effect on the agent’s character.) Me and philosophy: my decision to read philosophy contributes to my general bookishness now. Former Co-Worker: His decision to quit drinking contributes to his general bitterness and irritability now. Teddy Roosevelt: his decision to “toughen up” as a teenager contributes to his robust and ebullient personality as an adult. Mystic River: The boy’s decision to get in the car contributes to his pedophiliac impulses now. Kane’s Businesswoman: her decision to help rather than hurry contributes to her warm humanitarianism now. Kane’s Defense: Agenda • Kane’s 2-Prong Strategy: Kane attempts to establish that we have “Deeper Freedom” in two very different ways. • Self-Forming Actions (SFAs): The key concept in Kane’s argument. • Kane’s Unstated Argument: Kane’s argument that we author our actions. Kane’s Unstated Argument 1) Kane’s Assertion: We (normally) have control over and responsibility for our SFA’s. 2) Kane’s Assumption: if we have control over and responsibility for our SFA’s, then we have control over and responsibility for our APA’s. (C) Authorship: We (normally) have control over and responsibility for all of our actions. Assessing Kane’s Unstated Argument: Agenda • Kane’s Assertion: How does Kane establish control/responsibility for our SFA’s?. • Kane vs. the Evil Scientist: Kane thinks there’s a big difference between us and Al. • Kane’s Assumption: Does control over SFA’s imply control/responsibility for character? The Positive Argument: From Indeterminacy to Control “If she overcomes this temptation [i.e. her ambition], it will be the result of her effort, but if she fails, it will be because she did not allow her effort to succeed.” (p. 504, col. 2, top) 1) 2) The businesswoman’s effort to overcome her ambition explains her success if she succeeds. Her allowing the effort to fail explains her failure if she fails. (C1) Whichever way she acts, something she did explains why she acted that way. (C2) She controls and is responsible for her SFA. The Negative Argument: No Reason to Deny Control “[T]hese conditions taken together (that she wills it, and does it for reasons, and could have done otherwise willingly and for reasons) rule out each of the normal motives we have for saying that agents act, but do not have control over their actions (coercion, constraint, inadvertance, mistake, and control by others).” (p. 506, col. 1, top) (1) Kane’s List: The only reasons one can have for denying an agent control over and responsibility for her actions are: coercion, constraint, inadvertance, mistake, and control by others. (2) In the case of the businesswoman (and in similar cases of SFAs), none of these reasons apply. (C) The businesswoman (and similarly situated agents) controls and is responsible for her SFA. Assessing Kane’s Unstated Argument: Agenda • Kane’s Assertion: How does Kane establish that we have control over our SFA’s?. • Kane vs. the Evil Scientist: Kane thinks there’s a big difference between us and Al. • Kane’s Assumption: Does control over SFA’s imply control over character? Kane’s Responses to the Evil Scientist Argument Generic Response: The Analogy Premise is just wrong! More specific responses: Positive Argument Negative Argument Unlike Al and the Walden Two-ers, we have indeterminacy in our psychology. Unlike Al and the Walden Two-ers, we are not being manipulated by someone. Assessing Kane’s Responses • Kane’s two different responses can be countered by tweaking the Evil Scientist scenario so that the differences disappear. • We seem able to do this for both responses. • The argument against Authorship will then still work. Two Evil Scientists I hereby choose to raise my left arm! Lefty Curses! Foiled Again! Left? Right? ? (50% chance) Righty Indeterminacy in Al’s psychology without “authorship” 0 Evil Scientists I hereby choose to raise my arm! No manipulation and no “authorship” The Evil Scientist Argument (one last time) 1) Descriptive Premise: In the Evil Scientist Scenarios (±Universal Determinism), Al is not the “author” of his actions. In particular, Al is not responsible for what he does. 2) Analogy Premise: Our situation is exactly like Al’s (in at least one of the Evil Scientist Scenarios) in all relevant respects. (C) No Authorship: We are never the “authors” of our actions. In particular, we are not responsible for what we do. Assessing Kane’s Unstated Argument: Agenda • Kane’s Assertion: How does Kane establish that we have control over our SFA’s?. • Kane vs. the Evil Scientist: Kane thinks there’s a big difference between us and Al. • Kane’s Assumption: Does control over SFA’s imply control over character? Is Kane’s Assumption Correct? • Where, exactly, is the problem with Kane’s unstated argument? • Kane’s Assumption: if we have control over our SFA’s, then we have control over the changes in our characters that result from those SFA’s. • Recall some of the cases of SFAs. Were they all cases in which the agent has control over the changes in her character than resulted from those SFAs?