Rap and Poetry JayZ

advertisement

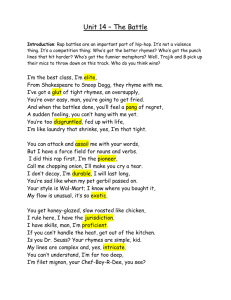

9th Honors Lit Rap, Poetry, Literary Devices, Identity EQ: How can I recognize the relationship between traditional poetry and rap music? “Empire State of Mind” by Jay-Z http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0UjsXo9l6I8 As you watch the video, quickly jot down visual images that strike you. How does Jay-Z use visual imagery to enhance the meaning of his verse? Yeah for foreigners it ain't for, they act like they forgot how to act [Verse 1: Jay-Z] Yea I'm out that Brooklyn, now I'm down in TriBeCa 8 million stories, out there in it naked City, it's a pity, half of y'all won't make it right next to Deniro, but I'll be hood forever I'm the new Sinatra, and... since I made it here Me, I got a plug, Special Ed "I Got It Made" If Jeezy's payin' LeBron, I'm payin' Dwyane Wade I can make it anywhere, yea, they love me everywhere Three dice cee-lo, three Card Monty I used to cop in Harlem, all of my Dominicano's right there up on Broadway, pull me back to that McDonald's Labor Day Parade, rest in peace Bob Marley Statue of Liberty, long live the World Trade Took it to my stashbox, 560 State St. catch me in the kitchen like a Simmons with them Pastry's Long live the King yo, I'm from the Empire State that's Cruisin' down 8th St., off white Lexus drivin' so slow, but BK is from Texas [Chorus:] [Verse 3: Jay-Z] Me, I'm out that Bed-Stuy, home of that boy Biggie Lights is blinding, girls need blinders now I live on Billboard and I brought my boys with me Say what's up to Ty-Ty, still sippin' mai tai's so they can step out of bounds quick, the sidelines is lined with casualties, who sip to life casually sittin' courtside, Knicks & Nets give me high five Xxxxx I be Spike'd out, I could trip a referee then gradually become worse, don't bite the apple eve Caught up in the in-crowd, now you're in style Tell by my attitude that I'm most definitely from.... Anna Wintour gets cold, in Vogue with your skin out City of sin, it's a pity on the wind [Chorus: Alicia Keys] Good girls gone bad, the city's filled with them New York, concrete jungle where dreams are made of There's nothin' you can't do Mami took a bus trip, now she got her bust out Everybody ride her, just like a bus route Now you're in New York These streets will make you feel brand new …Came here for school, graduated to the high life Ball players, rap stars, addicted to the limelight Big lights will inspire you Let's hear it for New York, New York, MDMA got you feelin' like a champion The city never sleeps, better slip you an Ambien New York [Verse 2: Jay-Z] [Chorus:] [Bridge: Alicia Keys] Catch me at the X with OG at a Yankee game xxxx, I made the Yankee hat more famous then a Yankee can One hand in the air for the big city Street lights, big dreams, all lookin' pretty You should know I bleed blue, but I ain't a Crip though but I got a gang of xxxxxs walkin' with my clique though No place in the world that could compare Put your lighters in the air Welcome to the melting pot, corners where we sellin' rock Everybody say "yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah" Afrika Bambataa xxxx, home of the hip-hop Yellow cab, gypsy cab, dollar cab, holla back Questions for Discussion: What themes does Jay-Z address in this song? How does his use of literary elements help bring out these themes? Where in the lyrics do you see layers of metaphors? What are the effects of his “language tricks” on you as a listener? Literary Elements Hunt Directions: Fill in the chart next to each literary element with an example from Jay-Z's lyrics. Allusion Biblical allusion Hyperbole Simile Metaphor Alliteration Personification Rhyme Double entendre Pun November 22, 2010 The New York Times Jay-Z Deconstructs Himself By MICHIKO KAKUTANI DECODED By Jay-Z Illustrated. 317 pages. Spiegel & Grau. $35. In the summer of 1978, when he was 9 years old and growing up in the Marcy housing projects in Brooklyn, Shawn Carter — a k a Jay-Z — saw a circle of people gathered around a kid named Slate, who was “rhyming, throwing out couplet after couplet like he was in a trance, for a crazy long time — 30 minutes straight off the top of his head, never losing the beat, riding the handclaps” of the folks around him, transformed “like the church ladies touched by the spirit.” Young Shawn felt gravity working on him, “like a planet pulled into orbit by a star”: he went home that night and started writing his own rhymes in a notebook and studying the dictionary. “Everywhere I went I’d write,” Jay-Z recalls in his compelling new book, “Decoded.” “If I was crossing a street with my friends and a rhyme came to me, I’d break out my binder, spread it on a mailbox or lamppost and write the rhyme before I crossed the street.” If he didn’t have his notebook with him, he’d run to “the corner store, buy something, then find a pen to write it on the back of the brown paper bag.” That became impractical when he was a teenager, working streets up and down the eastern corridor, selling crack, and he says he began to work on memorizing, creating “little corners in my head where I stored rhymes.” In time, that love of words would give Jay-Z more No. 1 albums than Elvis and fuel the realization of his boyhood dream: becoming, as he wrote in one of his earliest lyrics, the poet with “rhymes so provocative” that he was the “key in the lock” — “the king of hip-hop.” Part autobiography, part lavishly illustrated commentary on the author’s own work, “Decoded” gives the reader a harrowing portrait of the rough worlds Jay-Z navigated in his youth, while at the same time deconstructing his lyrics, in much the way that Stephen Sondheim does in his new book, “Finishing the Hat.” “Decoded” is less a conventional memoir or artistic manifesto than an elliptical, puzzlelike collage: amid the photo-sharp reminiscences, there are impassioned music history lessons that place rap in a social and political context; enthusiastic shout-outs to the Notorious B.I.G. and Lauryn Hill; remedial lessons in street slang (“cheese” and “cheddar,” the casual hip-hop tourist will learn, translate into “money”); and personal asides about the exhaustingly competitive nature of rap and the similarities between rap and boxing, and boxing and hustling drugs. At the same time, “Decoded” is a book that highlights the richly layered, metaphoric nature of the author’s own rhymes (even those about guns and girls and bling often turn out to have hidden meanings, stashed like “Easter eggs” in the weeds) — a book that underscores how the pressures of Jay-Z’s former life as a dealer honed his gifts as a writer, including a survivor’s appraising sense of character, an observer’s eye for detail and a hustler’s penchant for wordplay and control. Jay-Z has mythologized his life before, of course — many of his most resonant lyrics, particularly those on his autobiographical masterpiece, “The Black Album,” are works of willful self-dramatization. And the basic outlines of his Horatio Alger story are well known: his childhood in Bed-Stuy during the crack epidemic; his father’s departure from the family, leaving him “a kid torn apart”; his career as a dealer, “tryin’ to come up/in the game and add a couple of dollar signs to my name”; his debut album, “Reasonable Doubt,” in 1996 (by which time, he has said, he “was the oldest 26-year-old you ever wanted to meet”); his ascent as a rap star, followed by his success as a producer, an entrepreneur and a chief executive (“I’m not a businessman/I’m a business, man.”) Confidence is hardly in short supply for Jay-Z. This is the writer, after all, whose nickname is Hova (as in Jay-Hova), the rapper who has boasted of being “Michael Magic and Bird all rolled in one,” the “Sinatra of my day.” But Jay-Z writes here that he’s also tried, in his lyrics, to address emotions that “young men don’t normally talk about with each other: regret, longing, fear and even self-reproach,” and there are passages in this volume where the reader catches glimpses of the complicated, earnest artist behind the swaggering persona. As in the lyrics, such passages are often half-hidden. His father’s abandonment and the harsh code of the streets made Jay-Z, in his words, “a guarded person” — wary of feeling or exposing too much, and practiced in the art of detachment. And affecting moments of vulnerability (seeing his father many years later, he writes, was “like looking in a mirror,” and it “made me wonder how someone could abandon a child who looked just like him”) are stashed in footnotes, or scattered amid unsettling scenes from the author’s past, growing up in the projects when “teenagers wore automatic weapons like they were sneakers,” and dealing “crack to addicts who were killing themselves, collecting the wrinkled bills they got from God knows where, and making sure they got their rocks to smoke.” “Decoded” does not really grapple directly or in detail with several somber episodes in the author’s life, like his reported shooting, when he was 12, of his crack-addicted brother (who, according to a recent article in The Guardian, “did not press charges and apologized to his little brother for his addiction”), or his own narrow escape from what an article on Forbes.com has called “a failed attempt on his life” after “a dispute with rival dealers.” For that matter, this book — which thanks Dream Hampton, a former editor of the hip-hop magazine The Source, for her help — appears to be a variation on a more straightforward autobiography, written with Ms. Hampton, which Jay-Z decided not to publish several years ago. Shawn Carter’s past would supply the subject matter for Jay-Z’s best-known lyrics, and he notes here that when he began writing about his life and the lives of the people around him, “the rhymes helped me twist some sense out of those stories”: “flesh and blood became words, ideas, metaphors, fantasies and jokes.” Jay-Z neither romanticizes his days in the street nor apologizes for them, and while it may seem pretentious to supply detailed footnotes to a comical, party-down song like “Big Pimpin’,” his annotations to other lyrics are revealing. For instance, of the now ubiquitous “Empire State of Mind,” he says that when he first heard the gorgeous track, his decision was “to dirty it up,” to “tell stories of the city’s gritty side, to use stories about hustling and getting hustled to add tension to the soaring beauty of the chorus.” In doing so, he reminds us that this song, which has virtually replaced “New York, New York” as Gotham’s unofficial anthem, contains some remarkably raw references to drug dealing (“Welcome to the melting pot,/Corners where we selling rocks”) and promiscuous sex (“The city of sin is a pity on a whim,/Good girls gone bad, the city’s filled with them”). In the end, “Decoded” leaves the reader with a keen appreciation of how rap artists have worked myriad variations on a series of familiar themes (hustling, partying and “the most familiar subject in the history of rap — why I’m dope”) by putting a street twist on an arsenal of traditional literary devices (hyperbole, double entendres, puns, alliteration and allusions), and how the author himself magically stacks rhymes upon rhymes, mixing and matching metaphors even as he makes unexpected stream-of-consciousness leaps that rework old clichés and play clever aural jokes on the listener (“ruthless” and “roofless,” “tears” and “tiers,” “sense” and “since”). Just as Jay-Z’s eclectic sampling on his records affirms his postmodernist fascination with musical DNA, so this book attests to his love of music and respect for its history, and his debt to his parents’ incredible collection of LPs, “stacked to the ceiling in metal milk crates” — soul and R&B, pop and Motown and funk that he would “smuggle” into his own records and give new life to. “We were kids without fathers, so we found our fathers on wax and on the streets and in history, and in a way, that was a gift,” he writes near the end of this provocative, evocative book. “We got to pick and choose the ancestors who would inspire the world we were going to make for ourselves. That was part of the ethos of that time and place, and it got built in to the culture we created. Rap took the remnants of a dying society and created something new. Our fathers were gone, usually because they just bounced, but we took their old records and used them to build something fresh.”