Managing International Production. - An Introduction to International

advertisement

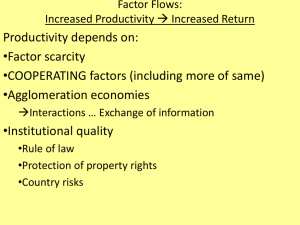

Chapter 11: Managing International Production An Introduction to International Economics: New Perspectives on the World Economy © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Analytical Elements Countries Sectors Tasks Firms © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Organizing the MNE Every MNE faces the two-fold decision regarding that tasks in which countries to include within its corporate boundaries In the case of Intel, these corporate boundaries are illustrated with solid lines in Figure 11.1 Within solid lines, intra-firm trade can take place Within dashed lines, inter-firm trade can take place Organizing the MNE involves both intra-firm design and inter-firm relationship considerations © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Figure 11.1: Intel’s Global Production Network for Semiconductors © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Intra-Firm Design As suggested in Table 11.1, before a firm begins the process of foreign market entry, it might consist of functional divisions With foreign market entry into a few countries, the firm might begin to set up a foreign division As foreign operations mature, there is a tendency to locate greater numbers of functions abroad One option for single-product, multi-country MNEs is country/regional divisions Each country or region covered by the MNE has its own division responsible for all functions © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Table 11.1: Generic Types of Intra-Firm MNE Design MNE Characteristics MNE Intra-Firm Design Singe product, single country Functional division Single product, few countries Single, foreign division Single product, multi-country Country/regional divisions Multi-product, few countries Product divisions Multi-product, multi-country Mixed structure based on matrix management or “heterarchy” © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Intra-Firm Design Another option associated with multiproduct, few country MNEs is that of a product division The most complicated case is that of the multi-product, multi-country MNE, and here, a standard approach is that of matrix management Each of the firm’s products has its own corporate division for global production and sales There are both product and country/regional dimensions to reporting lines Each of these are possibilities summarized in Table 11.1 © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Intra-Firm Design From the above, we can identify two general tendencies First, the narrower the range of its products, the more likely the MNE will adopt a country/region divisional structure Second, the wider the range of its products, the more likely the MNE will adopt a product divisional structure However, there is no complete set of principles that can guide MNE organizational design This lack of principles leaves MNEs pursuing heterarchy Heterarchy involves information sharing and informal ways of circumventing the limitations of formal organizational design © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Inter-Firm Relationships With regard to inter-firm relationships, an important issue is that of vertical connections to supplying firms As Gereffi, Humphrey and Sturgeon (2005) emphasized, MNEs with firm-specific assets (e.g., intangible assets) might engage in certain kinds of relationships that we can describe as contractual plus Market- market contracts are augmented by trust and normality achieved via repeated transactions Modular- suppliers organized around breakpoints in GPNs Relational- mutual dependence due of proximity or ethnic ties Captive- an asymmetric relationship in which the MNE is dominant over its suppliers © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Conclusions on Organizing the MNE MNE management in both it intra-firm design and inter-firm relationship components is a relatively complex and difficult task There is no single approach that can be grasped as the “answer” to multinational management There is an ongoing learning process that takes place, with varying degrees of success, within the historical trajectories of MNEs © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Joint Ventures Joint ventures (JVs) pose a set of challenges not generally encountered in merger and acquisition (M&A) and greenfield FDI The motivation for a JV usually reflects the presence of complementary firm-specific assets in the two firms involved JVs also occur in large, resource extraction FDI projects where both firms are interested in risk sharing and achieving large scale economies In some circumstances, the foreign-country government chooses to require JVs to ensure profit-sharing © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Joint Ventures Despite advantages in some circumstances, JVs are difficulty to negotiate, notoriously unstable and relatively short-lived The irony of JVs is that they tend to form due to differences between the firms involved, but these very differences make them difficult to manage Despite these difficulties, JVs remain an important component of international production © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 The Home Base Home bases are more than convenient addresses The home base of an MNE is in almost all cases the location of corporate headquarters Headquarters are important from the point of view of intra-firm design Home base environments can be important for the competiveness of MNEs Finance, corporate control and R&D tend to be centralized in home bases © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 The Home Base It is possible for these home bases to support the firmspecific assets that drive MNEs into international production This was the argument made, for example, by Michael Porter in The Competitive Advantage of Nations (1990) Porter identified four determinants of competitive advantage related to the home base factor conditions demand conditions related and supporting industries firm strategy, structure, and rivalry © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 The Home Base and Firm Competitiveness According to Porter Factor conditions Demand conditions Sophisticated, demanding, and anticipatory home demand contributes to firms’ success Related and supporting industries Sustained competitive advantage has its basis in the creation of advanced and specialized factors Supplier relationshipis can provide the MNE with betterdeveloped inputs and support innovation and upgrading Firm strategy, structure and rivalry There is an association between domestic rivalry and competitive advantage in an industry © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Spatial Clusters Malmberg, Sölvell, and Zander (1996) defined a spatial cluster as “a set of interlinked firms/activities that exist in the same local and regional milieu, defined as to encompass economic, social, cultural and institutional factors” Spatial clusters contribute to the productivity of firms The concentrated communication made possible by a cluster increases learning and innovation Trust increases over time, and this facilitates contracting and exchange among firms A common business culture develops, and this reduces uncertainty © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Research and Development There is a tendency to centralize R&D functions in the home base country or even in the corporate headquarters Given MNEs’ involvement in approximately three fourths of global, civilian R&D, the way in which MNEs configure R&D within their GPNs matters enormously to global technological capabilities The order of magnitude of R&D expenditures can be seen in Figure 11.2 © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Figure 11.2: R&D Expenditures (Source: UNCTAD) © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Research and Development A few considerations have motivated MNEs to begin decentralizing their R&D Advances in information and communication technology (ICT) The rise of emerging markets and the need to better tailor products to these markets New sources of talent and creativity for effective R&D, especially in China and India MNEs that want to tap into new sources of talent can either recruit it by bringing it to their home bases and other R&D sites or begin to relocate their R&D Many MNEs have chosen to relocate some aspects of their R&D © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 Research and Development Relocating R&D to new sources of scientific and engineering talent can make a great deal of sense Many MNEs are rethinking the role of R&D in their GPNs, choosing to locate specific kinds of R&D outside of the home base and developing regional R&D facilities that they link together in coordinated networks If a trend can be identified, it is for basic research (the R in R&D) to remain in the home base, with more applied research (the D in R&D) moving abroad The R&D element that is most likely to be dispersed throughout MNEs GPNs is the support laboratory © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012 US MNE Donaldson Testing Lab in Wuxi China Source: Aggregates Manager (www.aggman.com) © Kenneth A. Reinert, Cambridge University Press 2012