- James F. Daugherty

advertisement

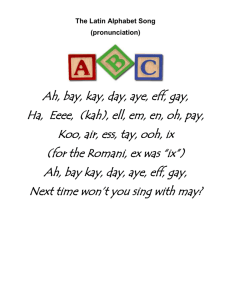

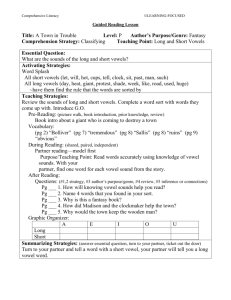

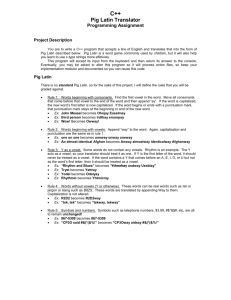

Resources for Teaching and Learning DICTION James F. Daugherty The University of Kansas From a musical / artistic perspective: CHORAL MUSIC HAS TEXT From a musical / artistic perspective: CHORAL MUSIC HAS TEXT Question: Why, then, are many philosophies of music education today based exclusively on models of absolute music, i.e., “music alone?” From an acoustical / scientific perspective: CHORAL MUSIC HAS TEXT IS Articulatory maneuvers produce UNITS OF SOUND: phonemes allophones vowels consonants words phrases “Good diction is the keystone in producing distinctive vocal and choral sound. Without good diction there is little prospect for other choral virtues such as blend of voices, sectional unity, variety in tone quality or color, proper use of resonation and even good intonation.” --Lloyd Pfautsch, English Diction for Singers (1971), p 3. “If a song is sung with poor diction (faulty articulation of vowels and consonants), much more than the literary meaning is lost; the quality of the singing voice is also impaired, resulting in a musical loss” --Charles Lindsley, Fundamentals of Singing, p 62 The articulatory capacity of the human voice most distinguishes it from other wind instruments. Resonance Articulation Phonation Respiration In its contributions to the human singing voice, articulation can sometimes be more important even than phonation (e.g., voiceless consonants) and resonance (e.g., articulators can block or open certain resonators) Some intuitively define singing as prolonged speech Fred Waring: “Sing all the beauty of all of the sounds of all of the syllables of all of the words.” Robert Shaw: “Don’t sing words. Sing all of the sounds of the words.” The final premise of our choral art…is that vocal (choral) music has words to communicate--as well as pitches, rhythms, and colors--and that it is possible most of the time to project them through and over instrumental collaboration. We do this by concentrating not upon the words themselves, but upon the irreducible, individual, and succession of sounds which form these words, and we try to allot to each of these sounds its precise moment of musical time. We amy take our personal inspiration from the text, but when it comes to the transmission of that text, it’s work gloves, overalls, and sweat. Robert Shaw FOOD FOR THOUGHT: Pence (1994) found that choral teachers surveyed were neither trained for, nor comfortable in, teaching diction. We spend a lot of time on pitches and rhythms, and we tend to believe that systematic sight-singing instruction is a means to musical literacy. Yet, we rarely consider systematically equipping our students with articulatory/phonetic tools for vocal literacy, despite the centrality of diction for choral sound and its demonstrated role in vocal/choral pitch and rhythm. In choral singing, this essential role of diction or articulation becomes more complex because of the CHORUSING EFFECT: Many voices and their reflections create a quasirandom sound of such complexity that the normal mechanisms of auditory localization and fusion are disrupted. Instability of F0 produces flutter. CHORAL SOUND: has properties of both complex tones and very narrow-band noise its sonic character is that of a sum of sounds that are similar, yet not phase coherent spectral beat (using LTAS) in the region of 500-700 Hz SPL of choral sound has large, random short-term variations due to beats Scientific studies of human singing find that people phonate and articulate differently in choirs than they do as soloists, i.e., solo singing and choral singing are two distinct modes of vocal production. Beyond a certain point, one cannot work with an ensemble of voices as one would work with a single voice in a studio. Simply put, choruses have to “chorus.” Matters such as perceived blend and balance become important. In chorusing, moreover, the whole is more than the sum of its parts. Put another way, chorusing vowels and chorusing consonants play somewhat different roles than solo vowels and solo consonants. Most importantly in this respect, they have to be perceived as being in some sense “unified.” It is this complex, perceived “unity” that determines both choral tone quality and some aspects of choral intonation. Intonation Issues Related to Diction Vowels themselves have intrinsic pitch: for example, all else being equal, high front vowels are generally produced with a higher Fo than low vowels. front vowels (like “ee” and “ih”) tend to raise the pitch (Fo) the “ah” vowel tends to lower the pitch (Fo) “u” (oo) has a relatively low number of harmonics and is perceived to drop in pitch the louder it gets, and to sharp in the presence soft reference tones translation: even given the same frequency at phonation, the pitch of some vowels will naturally sound flatter or sharper than the pitch of some other vowels. Certain combinations of vowels are particularly potent pitch/frequency benders: for example, “ee” to “eh” (as in Kyrie Eleison) can carry a change in Fo of almost 35 cents cent (a unit of frequency ratio that represents pitch deviation); one cent = 1/100 of a half step; 35 cents = about a fifth of step flat or sharp Solo singers typically can check their vowel tuning by a stable reference, e.g., a piano or an orchestra. A cappella choral singers (and to some extent all choral singers) have as a reference only fellow singers, who are fighting against the same vowel intonation tendencies. When, in a choral singer’s ear, the sound of the choir as a whole overbalances the feedback heard from one’s own voice (as in crowded spacing) a singer is much less able to modify intrinsic vowel pitch. To complicate matters further: two differing versions of a vowel going on simultaneously in a choral ensemble can also alter the overtones of the fundamental pitch produced by vibrations of the vocal folds. QuickTime™ and a Photo - JPEG decompressor are needed to see this picture. Translation: Choral singing “in tune” requires more than vocal folds phonating at on or around a certain frequency as indicated by notes in a score. It also requires articulation savvy. QuickTime™ and a Photo - JPEG decompressor are needed to see this picture. YOUR TURN So how do we teach the articulation necessary to sing this canon both beautifully and in tune? Four Teaching/Learning Strategies: 1. Que sera, sera whatever will be, will be 2. Modeling/Rote Perhaps momentarily quicker, but questionable transfer potential; teacher-centered, students equipped only to mimic the teacher Four Teaching/Learning Strategies: 3. English Phonetic Spelling similar to the Fred Waring tone syllable system For example: you--bee--lah--teh Can work more or less successfully for Latin. But not consistent or accurate for every language Shteal_lay Nahcht! Hi_lee_gay Nahcht! Often more than one symbol per sound, cannot always convey nuance. Still student-passive. 4. Established 1886, Paris. Revised 1993. Updated 1996. Major advantage over other systems: one sound, one symbol. Learn and teach any language. Empowers students with a useful tool. More useful over time. Major disadvantage: Need to learn the system first. (Not unlike solfegge in this respect). Pan (1995), in a study of an intact eighth grade choir (N=62), found that: Both IPA and English Phonetic Spelling were superior to traditional rote instruction as measured by individual testing on the correct pronunciation of a Latin motet the choir had been rehearsing. Students receiving instruction in IPA performed with significantly greater accuracy than students receiving instruction by phonetic spelling in being able to pronounce previously unstudied Latin texts. YOUR TURN hænd ov| ∂oz b√t\ns ør ju m´lt ! Sung Ecclesiastical Latin is a good starting point for IPA Choral Diction: It has 5 vowel sounds and only 5 vowel sounds It has no diphthongs Repeat: It has (should have) NO diphthongs Question: Given the absence of recording devices and the apparent presence of numerous dialects (Austro-German Latin, Venetian Latin, etc.), who determines how Ecclesiastical Latin should be sung? Answer: The Pope Papal Decree (1903), Pope Pius X required Roman pronunciation of Latin universally in the Roman Catholic Church This diction is codified in The Rev. Michael de Angelis, C.R.M., The Correct Pronunciation of Latin According to Roman Usage. Philadelphia: St. Gregory Guild. Rev. ed. 1937. 5 Latin Vowels å ´ i ø u 5 Latin Vowels å ´ i ø u ah, as in father eh, as in met ee, as in seek aw, as in bought, saw oo, as in soon 2 Latin Glides a glide is an unstressed vowel that proceeds quickly and smoothly to a following vowel j = unstressed i ju w = unstressed u kwi ju - bi - la -t´ a - l´ -lu - ja d´ -ø ju -bi - lla - t´ d´ - ø In terms of developing choral sound, especially in younger or amateur ensembles: Start with u: Most bang for the buck • u is the most physically active of the Latin vowels • need to round the lips, open the pharynx, release tension • can incorporate kinesthetic elements in its teaching • teach distinction between “Pepto-Bismol” u and “free” u Teach one at a time the 5 Latin vowels and the 2 Latin glides, along with their IPA symbols Can begin by incorporating them into daily warm ups Some strategies: 1. Teach the Jubilate Deo canon; it has them all (except the w glide), plus it contains the ubiquitous “alleluia” 2. During warm up exercises: have the IPA symbol(s) already on the board or wall and point to them in turn, perhaps adding one each day: both visual and aural reinforcement u ø i å ´ Strategies, continued: 3. focus on a particular vowel in already familiar u exercises, e.g., “I love t sing” anchor or modify with kinesthetic gestures 4. have on the board a “Pronounce That Word” or “Pronounce This Phrase” challenge (with the word or phrase written in IPA), similar to “Name That Tune” dIkß\n Iz f√n ßøn tßæst´:In raks ! Strategies, continued: 5. use various IPA symbols for sightsinging or rehearsing off text 6. download the IPA fonts and replace selected text with IPA symbols 7. occasional worksheets or online modules 8. gradually begin to use some IPA in memos and handouts YOUR TURN More IPA Symbols • \ = neutral unaccented schwa • √ = neutral accented uh, “up” • U = open as in “put,” “book” • † = unvoiced th as in “think” • æ = forward vowel, as in “cat” • ˜ = voiced, nasal consonant, • åU = diphthong, as in “cow” • I = open as in “it,” “him” • hw = unvoiced glide, as in as in sing “what” ∂ = voiced th as in “those” • diphthong is dIf †ø˜ nå:U Iz ∂\ m√n† √v m´:I˜ hw´n m´ri lædz år pl´:I˜ nå:U pl´: - I˜ få lå lå lå lå lå Iz ∂\ m√n† √v m´ - I˜ hw´n m´ -ri lædz år Altered to fit the context of a particular ensemble: nå:U pl´‘ - (I˜) få lå lå lå lå lå Iz ∂√ m√n∂ åv m´‘-(I˜) hw´n m´ -ri læ-dzår Altered to fit the context of a particular ensemble: nå:U pl´‘ - (I˜) få lå lå lå lå lå Iz ∂√ m√n∂ åv m´‘-(I˜) hw´n m´’-ri læ-dzår YOUR TURN Still More IPA Symbols • e = high vowel as in “chaotic” • ç = voiceless, forward ch somewhat as in “hue” • x = voiceless, back ch somewhat as in a sharply whispered “ah” • ø = close mixed vowel, ö • y = close mixed vowel, ü • o = closed o, as in “open” Ein Feste Burg ist unser Gott Unz\r gøt:t å:In f´st´ bUrk Ist ein Wehr und waffen å:In gut´ ver Unt våf:f\n der bö- se gute al-te Feind der ål-t´ bø-z´ få:Int mit Ernst er’s jetzt meint mIt ´rnst ers j´t:st må:Int gross macht gros:s måxt sein grausam und viel Unt fil List lIst Rüstung zå:In grå:Uzåm rystU˜ auf Erd ist å:Uf ert Ist nicht nIçt seins ist Ist gleichen zå:Ins glå:Iç\n å:In f´st´ bUrk Ist Unz\r gøt:t å:In gut´ ver Unt våf:f\n der ål - t´ bø - z´ få:Int mIt ´rnst ers j´t:st må:Int gros:s måxt Unt fil lIst zå:In grå:Uzåm rystU˜ Ist å:Uf ert Ist nIçt zå:Ins glå:Iç\n å:In der f´ - st´ bUrk Ist Un - z\r gøt:t å:In gu-t´ ver ål t´ zå:In grå:Uzåm Unt våf: - f\n bø - z´ få:Int mIt ´rnst ers j´t:st må:Int gros:s måxt Unt fil lIst ry - stU˜ Ist å:Uf ert Ist nIçt zå:Ins glå:I - ç \n YOUR TURN Even More IPA Symbols • Ω = voiced consonant, as in “azure” • • • • ´~ = nasalized ´ å~ = nasalized å o~ = nasalized o ß = fricative consonant sh, as in “ocean” and “sugar” il est ne le divin Enfant i l´ ne l\ di-v´~ å~ -få~ Jouez hautbois resonnez Ωu-we o-bwa il est ne le divin musettez reso~ne my-z´-t\ Enfant i l´ ne l\ di-v´~ å~ -få~ Chantons tous son avenement ßå~to~ tus so~ nå~-vå~~-n\-må~~ i l´ ne l\ di - v´~ ne my - z´ - t\ i l´ tus so~ na - vå~ -n\ -må~ å~ - få~ Ωu -we o - bwa res ne l\ di - v´~ å~ - få~ ßå~ Recommended Web Sites Listed on your handout Be sure to note: http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/~rogers/fonts.html download the IPA fonts for your word processing program for free..there is a set for Mac’s and a set for PC’s Recommended Books KU SUMMER GRADUATE COURSE CHORAL DICTION (3 credit hours) June 7 - 25, three weeks, 9am-Noon M-F for details: http://www.ku.edu/~memt moving the articulators causes shape, size, and length of vocal tract to change these changes allow the vocal tract to act as a filter on the sound produced by the vibrating vocal folds this sound source filtering, which includes the variable resonating frequencies of the vocal tract, determines the particular quality of a sound, i.e. which vowel is sounded different vowels are caused by different articulatory filtering for example, natural resonance frequencies of the vocal tract modify the signal generated in the vocal folds to ….. 1. Shteal_lay Nahcht! Hi_lee_gay Nahcht! Ah_lays shlayft; ine_sahm wahcht Noor dahs trou_tay hi_lee_gay Paar. Hole_dare Knahb' eem low_kig_ten Haar, |: Shlah_fay in him_lish_air Roo! :| 1. Stille Nacht! Heil'ge Nacht! Alles schläft; einsam wacht Nur das traute heilige Paar. Holder Knab' im lockigten Haar, |: Schlafe in himmlischer Ruh! :|