Products Liability

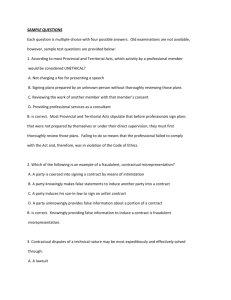

advertisement

Product Liability: A Review TECH-435 Legal Aspects of Safety Dr. E. Hansen, CIE, CHCM Northern Illinois University Department of Technology Introduction • The manufacturer of a product must exercise reasonable care to prevent injury to consumers and others who may come in contact with their product. This reasonable care includes insuring that the product is fit for its intended purpose. Product liability or negligence may also extend to dealers, sellers, suppliers, repairers and others within the product chain. Brief History While the product liability cases today stem from the Consumer Product Safety Act (CPSA) of 1972 ("CPSA," 1972) prior historical cases and events fueled the debate and subsequent passage of the act. • Prior to the turn of the century the general attitude was that of caveat emptor, or “buyer beware” based on common law. – “The logic was simple: people should examine what they are to receive before they buy it.” The origins for caveat emptor stem from “early English social and legal philosophy reflected [in] the manufacturing nature of the economy (Vaughn, 1999).” Two differing views on the “first case” of product liability: • McPherson v. Buick Motor Company (Vaughn, 1999) • Donaghue v. Stevenson (Vogt, 2000). Brief History: “First” Case # 1 In his book, Legal Aspects of Engineering, Richard Vaughn claims the origin of product liability stems from the McPherson v. Buick Motor Company case in 1916. • The plaintiff in the case suffered injuries when the wheel on his new Buick collapsed. • The judge ruled in favor of the plaintiff despite the use of the historical defenses of caveat emptor and privity of contract (an individual can not recover damages from the manufacturer, only the “middlemen”). • The judge’s “reasoning is virtually a statement of products liability law as it evolved years later.” It was also during this time that the philosophies of negligence and warranty were developed. (Vaughn, 1999) Brief History: “First” Case # 2 According to Susan Vogt, in her article Warning: Product liability law is extremely hot!, the first product liability lawsuit was Donaghue versus Stevenson decided the British House of Lords in 1932. • This case was about a snail that was almost swallowed by a woman who discovered it in a bottle of ginger beer. • “Its importance lies in the fact that the manufacturer was held liable, despite the absence of a contractual relationship, because the damages suffered were a foreseeable result of the manufacturer's negligence.” (Vogt, 2000) Theories of Product Liability Product Liability Negligence Breach of Warranty Strict Product Liability Breach of Express Warranty Breach of Implied Warranty Merchantability Theories of Product Liability (continued) • In most areas of the country the “plaintiff’s cause of action may be based on one or more of three different theories (Kionka, 1999)”: – Negligence – Breach of Warranty • Express warranties • Implied warranties • Merchantability and fitness for a particular use – Strict Liability Negligence • “is the committing of an act, which a person exercising ordinary care would not do under similar circumstances - or the failure to do what a person exercising ordinary care would do under similar circumstances.” (legal-definitions.com) Negligence Case Example Richelman v Kewanee Machinery And Conveyor Company • Suit based upon negligence and strict liability was brought against manufacturer designer as result of two-year nine-month-old child having suffered a traumatic amputation of his right leg when he became entangled in a grain auger located in his grandfather's farmyard. • The Circuit Court, St. Clair County, William P. Fleming, J., entered judgment, based on jury's findings, against manufacturer designer. Manufacturer designer appealed. • The Appellate Court, Moran, J., held that whether child's injuries upon inadvertently tripping or falling into open hopper was foreseeable was question for jury, inasmuch as defendant could "objectively expect" that if an adult with a smaller than 45/8 shoe width were to trip or fall near auger he could be injured because of inadequate safety guard. ("Richelman v. Kewanee Machinery And Conveyor Company," 1978) Breach of Warranty a warranty is an express or implied undertaking by a seller guaranteeing that the thing being sold is as promised (legal-definitions.com). • The primary breach of a “warranty” is the fitness of use of the product. • “Product liability law is primarily concerned with three of these warranties (Kionka, 1999): • Express warranties • Implied warranties • Merchantability and fitness for a particular use Express Warranties • The representations or promises relating to the material facts about the products, as described in salespersons’ statements, in pictures or writing on product or product packaging, and in advertisements persuaded the consumer to buy product. • A breach occurs when these representations are not true. • In other words an express warranty is “a promissory assertion of fact about the product which the seller made as a part of the sales transaction and which was a ‘basis of the bargain.” (Kionka, 1999) Implied Warranties • “those [warranties] created and imposed by law, and accompany the transfer of title to goods unless expressly and clearly limited or excluded by the contract.” (Kionka, 1999) • These warranties are not dependent on whether the manufacturer has made any actual statements or representations about its product. • “The implied warranty extends to both uses and that are reasonably foreseeable. An implied warranty extends to all persons who the manufacturer, seller, lessor, or supplier might reasonable have expected to use, consume or be affected by the goods.” (Bonsignore, 2003) Express/Implied Warranties Case Example Cipollone v. Liggett Group, Inc. • Cipollone is particularly notable for its legacy of preemption in interpreting the 1965 and 1969 Acts. Because merchants must properly package and label goods in order for them to be merchantable, the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the 1965 and 1969 Acts is crucial to an analysis of the implied warranty of merchantability. (Crawford, 2002) • If plaintiffs cannot bypass the preemption issues posed by Cipollone, then juries will never evaluate the merits of their claims and those causes of action will fail. (Crawford, 2002) Express/Implied Warranties Case Example (continued) • Rose Cipollone, a smoker for forty-two years, contracted lung cancer and filed suit against the Liggett Group, Inc., which had manufactured the cigarettes she had smoked. After Cipollone died from lung cancer in 1984, her husband, Antonio, continued the action as the executor of his wife’s estate. (Crawford, 2002) • The Cipollones’ complaint alleged many claims, including strict liability, negligence, breach of warranty, and intentional tort. After an interlocutory appeal and a $400,000 verdict for the Cipollones, the Third Circuit heard the case for the final time and affirmed the district court’s finding of a broad preemptive effect for the 1969 Act. (Crawford, 2002) Express/Implied Warranties Case Example (continued) • The Court of Appeals found that the 1969 Act preempts “state law damage actions” that “challenge . . . the propriety of a party’s actions with respect to the advertising and promotion of cigarettes.” Therefore, the “plaintiff’s post-1965 failure to warn, express warranty, and intentional tort claims” were preempted because they were based on the “advertising and promotion of cigarettes.” The Supreme Court subsequently granted certiorari for review. (Crawford, 2002) Express/Implied Warranties Case Example (continued) • Justice Stevens produced the most important opinion of the case, although it did not garner a majority of the Court. Stevens found that the preemptive effect of the 1969 Act barred “requirement[s] or prohibition[s]” imposed by state law relating to advertising and promotion of cigarettes, and therefore the 1969 Act would preempt most claims arising under state statutes and the common law. • The key question in the analysis is “whether the legal duty that is the predicate of the common-law damages action constitutes a ‘requirement or prohibition based on smoking and health . . . imposed under State law with respect to . . . advertising or promotion.’” • Justice Stevens concluded that the Cipollone’s claims for failure to warn, breach of express warranty, and fraudulent misrepresentation were preempted; however, the state law conspiracy claim remained. Despite the fractured nature of the Cipollone decision, most circuits have adopted Justice Stevens’s plurality opinion. (Crawford, 2002) Merchantability and fitness for a particular use • Merchantability and fitness for a particular use – “requires that the product (and its container) meet certain minimum standards of quality, chiefly that it be fit for the ordinary purposes for which the goods are sold. This includes a standard of reasonable safety.” • This is furthered with “fitness for a particular purpose” where the seller “knows or has reason to know” what specific purpose the goods sold will be used for and the purchaser of these goods is relying on the supplier to provide “suitable” goods. (Kionka, 1999) Merchantability Case Example SKAGGS V. CHAMPION INTERNATIONAL • Tim Skaggs, [born on March 5, 1950] died on October 17, 1991 from acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Tim worked for Simpson Lumber Company at its Arcata mill starting at age 21. His initial employment as a night shift laborer resulted in his working at various jobs, including assignments to the paint line department where he handled and sawed lumber treated with Woodlife, a wood preservative manufactured and sold to Simpson by Champion. • Although this action sought to hold Champion liable for negligence in not warning about the hazards of this product, which Champion knew was being handled improperly by its customers, and for breach of warranty, the primary legal basis for this action was for selling a defective product. (Alexander, 1998a) Merchantability Case Example (continued) • In the Skaggs case the plaintiffs claimed that Defendant Champion International was negligent in the production, retailing and distribution of Woodlife Clear RTU contaminated with dioxins and furans, was strictly liable for producing and distributing a defective chemical product and additionally liable for breaching an implied warranty that Woodlife with pentachlorophenal was of good and merchantable quality, safe and fit for its intended use. • It was also claimed that the Defendants knew this product was hazardous, misrepresented that it was safe to use and concealed from Simpson that many people inadvertently and routinely handled it in a dangerous manner. (Alexander, 1998a) Merchantability Case Example (continued) • The Skaggs case settled before Judge Michael Brown, following the denial of Champion's motion for summary judgment and after the completion of expert depositions before the scheduled trial. While denying liability, the Defendant paid $550,000 in settlement of all claims, a substantial recovery in Humboldt County where the primary industries are logging and fishing and average income is in the lowest twenty percent of California counties. (Alexander, 1998a) Strict Liability • “Under a strict liability standard, once the plaintiff establishes that a product is defective, liability results from that fact alone no matter how much care was applied during design, manufacture, marketing, distribution and sale (Larson, 2003).” • The term “strict,” in this situation, refers to the fact that the injured product user need not show negligence or fault. Commonly most states follow the rule of products liability as set forth in section 402A of the Restatement of Torts. Strict Liability Case Example Toole v. Richardson • Toole v. Richardson (1967) Cal.App.2d 689, 710, 60 Cal.Rptr. 398 involves the infamous MER/29. In affirming a jury verdict for the plaintiff’s eye damage as a result of inadequate warnings given with this prescription drug, Justice Salsman found there was substantial evidence to support the jury¹s verdict and award of punitive damages. On the strict liability question the court stated: • The possibility of eye injury and age was known to appellant before product was placed on the market yet no warning of this danger was given until the weight of accumulating evidence and the insistence of the FDA compelled it. Thus strict liability justified on the ground that the product was marketed without proper warning of its known dangerous effect. (Id., p.710.) (Alexander, 1998b) Restatements • Restatements are highly regarded distillations of common law prepared by the American Law Institute (ALI). • The goal is to distill the "black letter law" from cases, to indicate a trend in common law, and, occasionally, to recommend what a rule of law should be. • In essence, they "restate" existing common law into a series of principles or rules. • Restatements are not primary law, however they are considered persuasive authority by many courts. – Numerous Restatement sections have become primary law when a court or legislature has adopted its language (Harvard, 2003). Restatements (continued) • In 1998 the third edition of Restatements was published. • There have been debates and challenges to this edition. • Many states have adhered more closely with the second edition of the Restatements that was published in 1965. • The wording of section 402 and 403 of this Restatement is important: Restatements: s 402A Special Liability Of Seller Of Product For Physical Harm To User Or Consumer 1. 2. One who sells any product in a defective condition unreasonably dangerous to the user or consumer or to his property is subject to liability for physical harm thereby caused to the ultimate user or consumer, or to his property, if a. the seller is engaged in the business of selling such a product, and b. it is expected to and does reach the user or consumer without substantial change in the condition in which it is sold. The rule stated in Subsection (1) applies although a. the seller has exercised all possible care in the preparation and sale of his product, and b. the user or consumer has not bought the product from or entered into any contractual relation with the seller (Restatement of Torts, 1965). Restatements: s 402B Misrepresentation By Seller Of Chattels To Consumer 1. One engaged in the business of selling chattels who, by advertising, labels, or otherwise, makes to the public a misrepresentation of a material fact concerning the character or quality of a chattel sold by him is subject to liability for physical harm to a consumer of the chattel caused by justifiable reliance upon the misrepresentation, even though a. it is not made fraudulently or negligently, and b. the consumer has not bought the chattel from or entered into any contractual relation with the seller (Restatement of Torts, 1965). Basis for Product Liability Product Liability Basis Manufacturing Defect Design Defect Faulty Mfg. Process Malfunction Product or Packaging Reasonable Alternative Design Hardest to Prove Failure to Warn Failure to Warn Ineadequate Warning Basis for Product Liability • While the laws applicable to defective product cases varies from state to state, there are three legal theories common to all jurisdictions which may form the basis of a successful product liability case: – Manufacturing defect – Design defect – Failure to warn, or "inadequate warning Manufacturing Defect • In such cases the injury was caused as a result of defect in the manufacturing of the product. These cases are the hardest to prove, as evidence the example below is of a case that was lost. • Case example: Meli v. General Motors Corp. Meli v. General Motors Corp. • The plaintiff blamed an accident on a broken accelerator spring, but could not isolate a possible manufacturing defect that would have caused the accident, the Court found that the trial court properly granted a directed verdict to the defendant. • In addition to having been driven for over 32,000 miles, the vehicle had been serviced numerous times. • Because the accelerator spring had been exposed during service, there was no reason to conclude that a defect in manufacture was any more likely than negligent service to have been the cause of the accident. ("Sundberg v. Keller Ladder," 2002) Design Defect • In these cases the injury was caused by a poor design despite the fact that there may be no defect in the individual product itself. • This design defect is not limited to the product itself. Improper packaging resulting in safety related damage during shipping and handling may also be considered. – Case Example: Babcock v. General Motors Corporation Babcock v. General Motors Corporation • The [United States Court of Appeals] case arose from an accident on February 21, 1998, when a General Motors pickup truck driven by Paul A. Babcock, III, went off the road and struck a tree. The accident rendered Babcock a paraplegic. On June 15, 1999, Babcock died as a result of complications from his injuries • Plaintiff brought suit alleging negligence and strict liability against the defendant. ("Babcock v. General Motors Corp., 299 F.3d 60 (1st Cir. 2002)," 2002) Babcock v. General Motors Corporation (continued) • The jury returned a verdict finding GM liable on the negligence count and not liable on the strict liability count. It is undisputed that when Babcock was first seen after the accident his seat belt was not fastened around him. • The complaint alleged that Babcock was wearing his seat belt prior to the accident, but that the belt unbuckled as soon as pressure was exerted on it and the buckle released due to a condition known as "false latching." The main focus of the trial was on this claim of false latching. ("Babcock v. General Motors Corp., 299 F.3d 60 (1st Cir. 2002)," 2002) Babcock v. General Motors Corporation (continued) • The original case was proven by the plaintiff and awarded unspecified amount. This case was won largely in part of expert testimony. • The expert “determined crash speed by methodology generally accepted in accident reconstruction field and approved by National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) (Nordberg, 2003) .” His opinion was that the “seatbelt would have restrained passenger at that speed if nondefective and in use, and concluded from inspection of seatbelt that it had indeed been in use just prior to impact (Nordberg, 2003) .” He also showed an alternative design from Volvo that helps prevent false latching. • This case was affirmed and the court further awarded the plaintiff legal and court fees incurred during the appeals process. Failure to Warn / Inadequate Warning • These cases refer to injuries caused as a result of a product known to be potentially dangerous which was sold without warning labels or having inadequate labeling to properly warn the consumer. Including inadequate or no instructions for proper setup, use or maintenance. – Example of failure to warn: Gall v. Union Ice Co – Example of inadequate warning: Laramendy v. Myers Gall v. Union Ice Co • (1952) 108 Cal.App. 303, 230 P.2d 48 • Involved the absence of sufficient warning labels on drums of sulfuric acid that exploded. • Affirming verdicts for the plaintiffs, the court held that the question of defendants chemical companies' negligence in failing to place proper warning labels on sulfuric acid drums were for the jury (Alexander, 1998b). Laramendy v. Myers • (1954) 126 Cal.App.2d 636, 272 P.2d 824. A theatrical smoke-producing device set fire to a child's dress. • "The written directions which were with the device when it was received, warned: to hold the device away from the face while filling the hole with powder; and to stand back without making contact (when the device is on the floor) so that 'puff' will not strike face." • Notwithstanding these warnings the court found the warning was incomplete, affirmed a verdict for plaintiff, and held that the "defendants neglected to reasonably warn of the dangerous propensities of the device. … There was no warning of danger from fire." Id., at p.639. (Alexander, 1998b). Legal Stages Stages of Legal Process Stage 1 COMPLAINT Answer Third Party Move to Contribution Discovery Stage 2 Stage 3 DISCOVERY PRE-TRIAL Stage 4 TRIAL Motion to Includes Summary Move to Decision Dismiss Depostions Judgement Trial Defendent Dismiss Move to Discovery Accept Decsion Move to Appeal Stage 5 APPEAL Decision Plaintif Accept Decsion Move to Appeal Product Liability: Good & Questionable Results • Product liability cases have undoubtedly changed the way products reach consumers. • Product liability cases are on the rise. • The upside to these cases is consumers should be more confident in the products they buy. • Products should be safer and if a dangerous product causes an injury there have been precedents set to rectify the situation. • The downside, however is that with the increase in legitimate cases there has also been a rise in cases with little or no merit, individuals and ethically questionable attorneys out for an easy financial gain. Positive product liability cases 1 2 3 4 5 THE HARMFUL PRODUCT THE CORPORATE MISCONDUCT THE POSITIVE CHANGE Children severely burned by highly flammable pajamas. Riegel Textile aware of hazard, but chose not to treat pajamas with flame-retardant chemicals. Playtex willfully disregarded studies and medical reports linking product to Toxic Shock. Johnson & Johnson knew of danger for years, yet instructed agents not to mention it to clients. Airco was aware its design was risky. $1 million punitive award forces unsafe product off the market. Ford knew of defective transmission design, yet failed to warn consumers. Transmission safely redesigned after $4 million punitive award. Women dying from Toxic Shock Syndrome after using super- absorbent tampons. Tylenol turns toxic, destroying liver when mixed with alcohol. Faulty surgical ventilator cuts off oxygen supply, causing brain, lung damage. Defect in car transmission causes automobile to suddenly move in reverse. Deadly product removed from market after $10 million punitive award. $8.8 million award spurs company to put warnings on its products. Airco issues medical device alert after $3 million punitive award. Source: http://www.atla.org/secrecy/data/differ.aspx (ATLA, 2001) Positive product liability cases (continued) THE HARMFUL PRODUCT THE CORPORATE MISCONDUCT THE POSITIVE CHANGE 6 Young athletes dying from head, spinal injuries due to unsafe football helmets. Manufacturers slow to acknowledge danger of their poorly designed product. 7 Arthritis pain-relief drug causes fatal kidney-liver ailment. Eli Lilly knew of hazard, but failed to inform doctors, patients and FDA. After inhaling asbestos, workers contract asbestosis, which causes lung cancer. Babies tragically being hanged to death on headboard of crib. Manufacturers knew danger of asbestos for decades, but concealed risk from public. Defective minivan door latch responsible for 37 deaths, 98 injuries and 134 ejections. Chrysler knew latch was unsafe, yet did not take steps to fix design or warn consumers. Liability claims spur improved helmet design; no deaths for first time in 60 years. $6 million punitive award forces company to remove drug from world market. Asbestos taken off market thanks to liability claims and punitive damages. Company stepped up recall of crib, public notification effort after $475,000 punitive award. Latch redesigned, old latches replaced in response to class action lawsuit, NTSB pressure. 8 9 1 0 Bassett Furniture, which had stopped making crib, failed to notify owners of hazard. Source: http://www.atla.org/secrecy/data/differ.aspx (ATLA, 2001) Questionable Results • Product liability cases have encouraged manufacturers to design, manufacture and distribute safer products. However, with the potential for, and increasing numbers of, frivolous lawsuits something should be done to regulate the current system. This is not to say that society should return to the days “buyer beware,” but rather the system needs to move away from the current trend of “seller beware.” • Two cases with questionable results: – The McDonald’s Coffee Case – Carrying a Full Fish Tank Full of Water The McDonalds Coffee Case • In February of 1992 a New Mexico senior citizen, Stella Liebeck, was a passenger in her grandson's car when she suffered third-degree burns from McDonald's coffee. • After receiving the coffee from the drive-through window, the grandson pulled over to allow his grandmother to add cream and sugar to her coffee. In attempting to remove the plastic lid, the coffee spilled into her lap causing severe burns to her upper thigh area. • She was hospitalized for eight days, during which time she underwent numerous skin grafts. When McDonalds's refused to settle the case for $20,000, the grandmother retained an attorney to file charges against McDonald's. • During discovery, documents obtained from McDonald¹s showed more than 700 claims by people burned by its coffee between 1982 and 1992, proving that McDonald's had knowledge of the dangers of their product. The McDonalds Coffee Case (continued) Other facts in the case: • McDonald's quality assurance manager testified that the company actively enforces a requirement that coffee be held in the pot at 185 degrees, plus or minus five degrees • Plaintiff's expert testified that liquids, at 180 degrees, will cause a full thickness burn to human skin in two to seven seconds. • McDonald's asserted that customers buy coffee on their way to work or home, intending to consume it there. • The jury awarded Liebeck $200,000 in compensatory damages. This amount was reduced to $160,000 because the jury found Liebeck 20 percent at fault in the spill. The jury also awarded Liebeck $2.7 million in punitive damages. • The trial court subsequently reduced the punitive award to $480,000. • The judge called McDonald's conduct reckless, callous and willful. Source: Consumer Attorneys Association of Los Angeles (CAALA) The McDonalds Coffee Case (continued) • The questionably “positive” result is that now McDonalds places the following warning on their coffee cups: “Warning: Contents Hot.” • In this author’s opinion this case was completely frivolous with no benefit to safety whatsoever: “Most people, except the very young or the mentally disadvantaged, would expect that hot coffee would be hot. But our courts and our judges seem to have retreated from the reasonable person standard in holding companies liable for product misuse.” (Smith, 1997) Carrying a Full Fish Tank Full of Water Source: Mealey's Litigation Reports (mealeys.com, 2003) • SALEM, Ore. -- A plaintiff who won a jury verdict after she was seriously injured by a shattering fishbowl has less than four weeks to decide whether to accept remittitur of her punitive damages award or face a new trial to set the proper amount (Arleen E. Waddill v. Anchor Hocking, Inc., No. A91012, Ore. App.). – The case was back before the Oregon Court of Appeals after the U.S. Supreme Court, citing State Farm v. Campbell (538 U.S. __, 123 S. Ct. 1513 [2003]), vacated the $1 million award based on compensatory damages one-tenth the size. Carrying a Full Fish Tank Full of Water (continued) • Arleen E. Waddill was carrying a fishbowl containing water in her arms when the glass bowl shattered, slicing the ulnar artery, ulnar nerve and a tendon in her left arm and lacerating the index finger and an artery and nerve on her right hand. • Waddill suffered lingering pain, numbness and weakness in her arms that her physician told her would be permanent. • Waddill sued Anchor Hocking Inc., which made the fishbowl, complaining that the company failed to attach a warning to the fishbowl against carrying it when loaded with water. Source: Mealey's Litigation Reports (mealeys.com, 2003) Carrying a Full Fish Tank Full of Water (continued) • Anchor Hocking knew of three other incidents in which customers were injured in similar circumstances but did nothing to improve the product's safety and in fact destroyed records pertaining to those incidents, she alleged. • A Multnomah County Circuit Court jury found that Anchor Hocking was negligent and that the fishbowl was dangerously defective because of the company's failure to affix an appropriate warning. • It assessed actual damages of $132,472, reduced to $100,854 by the jury's finding that Waddill was 25 percent at fault, and awarded $1 million in punitive damages. Source: Mealey's Litigation Reports (mealeys.com, 2003) Carrying a Full Fish Tank Full of Water (continued) • A panel of the Oregon Court of Appeals affirmed the judgment in its entirety, finding that the jury's decision to award punitive damages complied with both state and federal law, including the U.S. Constitution's 14th Amendment. • The U.S. Supreme Court, however, granted certiorari to Anchor Hocking, vacated the award and remanded to the appellate court for further consideration in light of State Farm. – The panel concluded that the maximum constitutionally permissible award in the instant case was four times the compensatory damages, or $403,416. – However, it offered Waddill the choice of accepting the reduced amount or consenting to a new trial to establish a more appropriate level of punitive damages. Source: Mealey's Litigation Reports (mealeys.com, 2003) Carrying a Full Fish Tank Full of Water (continued) • The questionably “positive” result is not yet known, as the new trial has not yet been set. • Undoubtedly, Anchor Hocking will have to place a warning label so that people know not to carry a full fish tank full of water. • Sympathy is felt for the individual and resulting injuries, but should Anchor Hocking have to pay for her lapse in judgment? • Humanity will not be better served if a warning label is affixed to every fish tank that says: “Warning: Full Fish Tanks May Cause Injuries If Carried When Full Of Liquid.” Warning Label Overkill • Many people question the validity of warning labels on products. • The litigious nature of our society has manufacturers affixing labels to protect themselves from these rising court costs and people out to make easy money. • The following slide contains a few warning labels that are obviously due to product liability laws and generous courts. Warning Label Overkill (continued) The Consumer Alert website provides the following eight real warning labels as examples of “warning overkill:” • Box of staples: "Caution: Staples have sharp points for easy penetration so handle with care." • Car sun shield: "Do not drive with sun shield in place." • Sled: "This product does not have brakes." • Marbles: "Choking hazard - This toy is a marble.” • Ladder: "Do not overreach." • Child's play helmet: "This is a toy." • Hair dryer: "Do not use while sleeping." • Roller blading: "Learn how to control your speed, brake and stop.“ (Smith, 1997) What Does Tort Liability Cost? According to statisticians at the U.S. Department of Justice: • Juries in the 75 largest counties disposed of 12,000 tort, contract, and real property rights cases during a 12-month period ending June 30, 1992. • Jury cases were 2% of the 762,000 tort, contract, and real property cases disposed by State courts of general jurisdiction in the Nation's most populous counties. • Thirty-three percent of cases decided by juries were automobile accident suits. (DeFrances; et al.) What Does Tort Liability Cost? (continued) • 11% were medical malpractice • 5% were product liability and toxic substance cases. • In half of all jury cases, the jury found in favor of the plaintiff and in the 12-month period awarded an estimated $2.7 billion in compensatory and punitive damages. • The median total award for a plaintiff was $52,000. • Punitive damages were awarded in 6% of the jury cases with a plaintiff winner. • Median punitive award was $50,000; average time from complaint filing to jury verdict was 2.5 years. (DeFrances; et al.) What Does Tort Liability Cost? (continued) • Claimants and plaintiffs are paid for economic losses sustained. • Additionally they are paid for non-economic losses, such as pain, suffering, claimant’s attorneys’ fees and administrative costs. • A reflection of the cost of the tort system is the price of liability insurance in defense of these claims (III, 2003b). What Does Tort Liability Cost? (continued) U.S. TORT COSTS RELATIVE TO GDP AND POPULATION Year 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2001 U.S. tort costs ($ billions) U.S. GDP ($ billions) Tort cost as % of GDP U.S. population (millions) $1.80 5.4 13.9 43 129.6 179.7 205.4 $294 527 1,040 2,796 5,803 9,825 10,082 0.61% 1.03% 1.33% 1.54% 2.23% 1.83% 2.04% 152 181 205 228 249 281 285 Inflationadjusted (1) Tort cost per tort cost citizen per citizen $12 30 68 189 520 638 721 (1) Restated in year 2001 dollars. Source: Tillinghast-Towers Perrin. through www.iii.org $87 180 309 406 704 657 721 Conclusion Product liability cases have encouraged manufacturers to design, manufacture and distribute safer products. Furthermore, product liability cases have rightfully forced these same manufacturers to properly warn consumers of the potential dangers with their products. However, with the potential for, and increasing numbers of, frivolous lawsuits something should be done to regulate the current system. This is not to say that society should return to the days of caveat emptor, or “buyer beware,” but rather the system needs to move away from the current trend of “seller beware.” Conclusion (continued) In 1992, on the campaign trail, the first President Bush (George H. Bush) summed it up best when he made the following remarks: “Product liability laws vary from State to State, and the rules have encouraged these crazy lawsuits and outrageous awards. And the cost of insurance keeps going right out through the roof, keeps skyrocketing. Big deal, right? So companies have to pay extra for a few lawyers. But it's not just companies who foot the bill; we all pay higher prices for everything from medicine to stepladders. We never get to see a lot of good products because companies are afraid of excessive lawsuits (Bush, 1992).” Conclusion (continued) “In 1985 Senator Robert Kasten of Wisconsin introduced legislation that would replace the current open-ended system with uniform rules (Hansen, 2003).” This legislation was in response to the fact that “almost half of all the money paid out in these kinds of cases goes not to the injured party, but to the lawyers (Bush, 1992).” Senator Kasten led the charge for reform but lost his senatorial seat in 1992. Since then various reform measures have been proposed. One of the reforms suggested was to limit punitive damages to the first successful claimant in suits involving a single product and a single manufacturer. Another reform suggested was to “cap” non-economic damages at $100,000 or $250,000. (III, 2003a) Conclusion (continued) There is evidence of a changing attitude towards excessive claims. In 2001, the U.S. Supreme Court said that appellate courts must “carefully analyze the evidence used to determine the amount of an award for punitive damages, rather than rely on the judgment of the trial court, to ensure that the rights of both individuals and corporations are protected.” (III, 2003a) The federal government should impose limits and pass some level of tort reform because without clear limits there can be dramatic and excessively costly deviations from realistic damages. Source Information Alexander, R. (1998a). Dioxin In Pentachlorophenol: A Case Study Of Cancer Deaths In The Lumber Industry. Retrieved November 22, 2003, from http://consumerlawpage.com/article/lumber.shtml Alexander, R. (1998b). Product Liability Warning Cases. Retrieved November 22, 2003, from http://consumerlawpage.com/article/failure.shtml ATLA, (2001). Cases That Made A Difference: Product Liability Cases Make America Safer. Retrieved November 9, 2003, from http://www.atla.org/secrecy/data/differ.aspx Babcock v. General Motors Corp., 299 F.3d 60 (1st Cir. 2002), No. 01-2270 (United States Court of Appeals, First Circuit 2002). Bonsignore, R. J. (2003). Injuries From Defectively Designed Automobiles/Suv's/Trucks And Other Motor Vehicles. Retrieved November 20, 2003, from http://www.bandblaw.net/auto.htm Bush, G. (1992). Remarks at the Republican Party Labor Day Picnic in Waukesha, Wisconsin. Retrieved November 22, 2003, from Source: http://bushlibrary.tamu.edu/papers/1992/92090701.html CAALA.The McDonald's Coffee Case. Retrieved November 21, 2003, from http://www.caala.org/NewsMedia/ProductLiability.asp Consumer Product Safety Act, 15 37 (1972). Crawford, F. E. (2002). Fit for Its Ordinary Purpose? Tobacco, Fast Food, and The Implied Warranty of Merchantability. The Ohio State Law Journal, 63(4). DeFrances;, C. J., Smith;, S. K., Langan;, P. A., Ostrom;, B. J., Rottman;, D. B., & Goerdt, J. A. (1995). Civil Justice Cases and Verdicts in Large Counties (No. NCJ-148346). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice. Hansen, D. E. E. C., CHCM. (2003). Class Notes: Products Liability. DeKalb, IL: University Bookstore Print Services: Northern Illinois University. Harvard, L. S. (2003, August 8, 2003). Restatements Generally. Retrieved November 20, 2003, from http://www.law.harvard.edu/library/research_guides/restatements.htm Source Information (Continued) III. (2003a, October 2003). The Liability System. Retrieved November 22, 2003, from http://www.iii.org/media/hottopics/insurance/liability/ III. (2003b, October 2003). The Tort System and Liability Insurance. Retrieved November 22, 2003, from http://www.iii.org/media/facts/statsbyissue/litigiousness/ Kionka, E. J. (1999). Torts In A Nutshell (Third ed.). St. Paul, MN: West Group. Larson, A. (2003, September 2003). Product Liability Law - Protecting Consumers from Defective Products. Retrieved November 20, 2003, from http://www.expertlaw.com/library/pubarticles/Product_Liability/product_liability.html legal-definitions.com.Negligance Definition. Retrieved November 19, 2003, from http://www.legal-definitions.com/ legal-definitions.com.Warranty Definition. Retrieved November 19, 2003, from http://www.legal-definitions.com/ mealeys.com. (2003, November 3, 2003). Product Liability Punitive Award Reduced; Plaintiff To Decide Whether It's Enough. Retrieved November 9, 2003, from http://www.mealeys.com/stories_prod.html#1 Nordberg, P. (2003, November 22, 2003). Engineers. Retrieved November 23, 2003, from http://www.daubertontheweb.com/Engineers.htm Restatement of Torts. (Second ed.)(1965). American Law Institute. Richelman v. Kewanee Machinery And Conveyor Company (Appellate Court of Illinois, Fifth District 1978). Smith, F. B. (1997). Warning Label Overkill. Retrieved November 21, 2003, from http://www.consumeralert.org/pubs/research/may97.htm Sundberg v. Keller Ladder (U.S. District Court of Eastern District of Michigan Northern Division 2002). Vaughn, R. C. (1999). Legal Aspects of Engineering (Sixth ed.). Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. Vogt, S. (2000, February 14, 2000). Warning: Product liability law is extremely hot! Strategy Magazine, 20.