Financing Cost and Risk Sharing in Islamic Finance A New

advertisement

Financing Cost and Risk Sharing in Islamic Finance

A New Endogenous Approach1

Fayçal Amrani2

Abstract

This paper suggests a new explanation to the low presence of Profit and Loss Sharing (PLS)

contracts in Islamic banks balance sheets. At the opposite of the mainstream literature that

explains this trend exclusively by supplies factors as moral hazard and adverse selection, we

demonstrate that the banishment of the PLS contracts is due to demands factors, and more

specifically, the way used to price the margin profit of the other main contract category: the

mark-up contracts. The current pricing practices of Islamic finance institutions lead to double

price in the market. We called this situation “artificial adverse selection” and we suggest a

new way of calculation to unify the financing cost of those two main categories of contracts.

This allows us to restore the condition of their coexistence in the market. The endogenous

profit margin we model is a function of the optimal share ratio of the PLS contract and its

default probability but also a function of the risk aversion of the entrepreneur. Furthermore,

our endogenous modeling allows us to distinguish between the Islamic mark-up contracts and

the conventional loans according to criteria as legal structuring and economic factors taking

into account for theirs remunerations.

Keywords: Risk Sharing, Pricing, Artificial Adverse Selection, Mark-up, PLS

1

This paper has already been presented at the 29th International Symposium on Money, Banking and Finance

(June 28-29, 2012 Nantes-France) of the GdRE (European Research Group).

2

PhD Candidate, LEDa- SDFi Department, Paris-Dauphine University.

E-mail: faycal.amrani@dauphine.fr

Telephone number: 00 336 68 70 43 30

1

Introduction

According to Islamic finance literature and industry, the main feature of Islamic Finance

practices is their strong commitment to the Profit and Loss Share (PLS) contracts. Indeed, at

the beginning of the modern Islamic banking industry, mark-up contracts were considered as

an exception since PLS contracts were the rule. For instance, the Murabaha contract, currently

the archetype of the mark-up contract, was designed and launched as a subsidiary contract.

Several authors have supported, for a long time, the superiority of the PLS contracts against

conventional financing, means using interest rate, but also against the other forms of Islamic

contracts. Besides, a large section of the literature is dedicated to prove this supremacy.

For example, Presley and Sessions (1994) demonstrate that sharing contracts, such as the

Mudharaba, under certain conditions, improve the information quality spread by the manager

to the investors.

Nonetheless, Islamic Finance Institutions (IFI) moved away gradually from this original

paradigm: PLS contracts step aside in favor of mark-up contracts. This situation has also been

described by several authors and confirmed by different IFI balance sheets analysis.

Dar and Presley (2001), in a paper entitled "Lack of Profit Lost Sharing in Islamic Banking",

note that the ongoing IFI practices are far from the theoretical model based on Mudharaba or

Musharaka contracts. Almost the entire financing projects of Islamic banks, companies and

funds are structured with commissions, mark-up or leasing contracts.

Aggarwal and Youcef (2000) made a summary of the PLS contracts used by banks since the

emergence of the contemporary Islamic Finance. This study includes countries where Islamic

finance coexists with conventional banking, like Egypt, but also countries where the financial

system as a whole is exclusively regulated by Islamic law, like Iran for example. The main

result of this study is the low proportion of PLS contracts in bank’s balance sheets.

2

Based on the data of the central bank, Yasseri (2002) presents an overview of the Iranian

banking system from 1995 to 1998. In 1995, the Mudharaba and Musharaka represent 26% of

the total financing contracts against 45% of forward sell contracts including Murabaha. This

trend is confirmed in 1998 with only 16% for both Mudharaba and Musharaka of the total

financial contracts, while the proportion of the mark-up rose to 56%.

In Malaysia, the biggest Islamic finance market in the world, PLS contracts are used at a very

low level by the finance industry.

For the current period, on 31st December 2010, the balance sheets of the three biggest IFI

show the following assets breakdown3:

1. Dubai Islamic Bank: PLS (22%), Murabaha (29%), others (none PLS contracts)

(49%).

2. Qatar Islamic Bank: PLS (3.1%), Murabaha + Mussawama (69.75%), others (nonPLS contracts) (27.15%).

3. Emirates Islamic Bank: there is no allusion to any kind of PLS financing, all of them

are none PLS Contracts.

By setting up a theoretical framework compliant with the Islamic law, under which the IFI are

supposed to deal with, this paper suggests a new explanation to the banishment of the PLS

financing from the IFI and we also set the conditions necessary to the coexistence of those

two categories of contracts.

While the mainstream literature explains the failure of PLS contracts in Islamic banks by the

insufficient supply of those contracts in the market, we will in this paper present an opposite

explanation, in which we demonstrate that the main reason of this situation is due to the

demand factors: the current calculating system of PLS contracts margin profit dissuade PLS

contracts demand from the managers. Actually, the current exogenous profit margin of the

3

It should be noted that these proportions are calculated in relation to total assets of investment and financing

(deposits at the central bank are not taken into account).

3

mark-up contracts used by the IFI lead to a dual pricing, generally prejudicial to PLS

contracts that can coexist with mark-up contracts only if their financing costs are equalized.

This result allows us to define the conditions that IFI should take into account to set the

appropriate endogenous mark-up: the new calculated mark-up integrates not only the

structural characteristics of the contracts but also the perception of risks involved by those

contracts from the managers.

The paper is organized as follow: at first, we present and define the two main categories of

Islamic Finance contracts in Section I. Then, in Section II we look over the prevalent

conclusions in the literature concerning the disappearance of PLS contracts in IFI. After that,

we propose in Section III an alternative explanation to this banishment, and then, a margin

profit model is put forward in Section IV. We conclude in Section V.

I- Mudharaba and Murabaha

The PLS category contains a certain number of contracts based either upon profit and lost

sharing as the Musharaka, with its different varieties, or only on the sharing of profit as the

Mudharaba. The only profit sharing profit sub-category, along with the Murabaha, will be

studied in the current paper. The results that came out are not substantially different from the

other PLS contracts.

Firstly, the Mudharaba is a contract that links two parties: the IFI (fund contributors or Rabel-mel) and the entrepreneur/contractor (Mudharib). The aim is to provide the required funds

to a party that has the capacity to achieve such a project. If the entrepreneur makes profit, it

will be shared between the two parties according to a prefixed ratio. However, if there is a

loss the funds provider (the IFI) will absorb it fully. As for the entrepreneur, his efforts would

be his only loss, which represents an “opportunity cost”.

Secondly, the other largest Sharia-compliant funding category is based upon profit margins

(mark-up). The main contract of this category is the Murabaha: it is the combination of three

4

different contracts linking the IFI to his client and his supplier. Firstly, the client submits a

purchase order to the IFI to buy a specific commodity. This purchase order comes with a firm

commitment from the organizer to buy the commodity once the IFI has purchased it. The

second contract binds the IFI as the buyer to the provider of the commodity. Thirdly, the IFI’s

client honors his commitment by purchasing the ordered commodity. Thus, its ownership is

transferred to the client when the purchase/ sale contract is signed. On the other hand, the

organizer owes the IFI a debt: he will pay at a given date or on a number of installments a

fixed amount that includes the price of the commodity and a profit margin set by the IFI, or

the Ribh, this is why it is called Murabaha. The set purchase/sale price of a Murabaha

transaction can never vary, neither due to an economic situation, nor to the non-compliance of

due dates. If the client is in good faith and he is unable to honor his commitments because of

extraordinary events, the IFI cannot impose extra charges and has to bear this kind of risk.

II- PLS Contracts in the Literature: the Reasons of a Banishment

Even if the first generation of Islamic finance literature praised the PLS contracts, the practice

of IFI has led researchers to try to determine the reasons of the banishment of these contracts.

The main argument developed in the second generation of the works focused on identifying

the defects inherent to these contracts. Mark-up dominance is explained almost exclusively by

the IFI’s will to limit the offer of PLS. Moral hazard problem and more generally agency

issues are in the heart of this argumentation.

Khalil, Rickwood and Murinde (2002) distinguish two types of agency problems regarding

the Mudharaba. The first one is the adverse selection problem arising from ex-ante

asymmetric information between the bank and his partner (talents, experience, ingenuity of

the entrepreneur and project viability). The second cover ex post asymmetric information.

Namely, moral hazard problems associated with the non-disclosure of the actual results and

5

the difficulty of observing the actions of the entrepreneur, which limits the control of his

discretionary power regarding decision of production and investment. Their conclusion is

unambiguous: in this type of contract, the problems of adverse selection and moral hazard are

so important that the PLS principles become inapplicable.

Aggarwal and Yousef (2000) defend the same point of view: considering that the IFI limit

their use of PLS because of the high level of moral hazard. The authors think that the Islamic

mark-up contracts, close to conventional debt, are more profitable for banks. The PLS or the

combinations of PLS and mark-up contracts could be optimal only if the level of moral hazard

is sufficiently low.

Jouaber and Mehri (2011) raise also the informational problem: despite their efforts to model

an optimal Mudharaba sharing profits ratio to face the problem of adverse selection, they also

explain the non-use of PLS by serious agency problems such as moral hazard and adverse

selection.

In a study based on a qualitative survey of a sample of Islamic banks managers, Habib and

Khan (2002) consider that the IFIs prefer mark-up models because of the high risky nature of

PLS contracts. The results of this survey highlight the fact that the bank managers have a high

aversion to the risks inherent to this type of contracts. This survey, which covers seventeen

Islamic banks, shows that they give an excessive importance to the risks related to PLS

contracts. According to these results, the Murabaha is the less risky contract from the banks’

point of view and the diminishing Musharaka, which is a PLS contract, the more risky one. In

other words, due to the high level of risks observed by the managers in the PLS contracts, the

IFIs avoid their use, and it would be the case as long as they could find out an alternative way

to finance their clients.

Other factors are sometimes mentioned in the literature to explain the Islamic banks distrust

of PLS contracts. Some authors suggest the weak regulation of property rights; the tax

6

treatment which is biased in favor of the conventional financing…etc. (Dar and Presley

2001). However, these arguments could be easily overcame and depend more on conjectural

factors than inherent characteristics of PLS.

Khan (1995) is one of the few authors who attempted to explain the lack of PLS by demand

factors, that is to say by taking into account the willingness of entrepreneurs to use these

contracts. He rejects the mainstream explanation that Islamic banking is in a position to

impose a particular form of contract to its clients. He suggests, therefore, to analyze

simultaneously the supply factors (sources of IFIs reluctance for PLS contracts) and demand

factors (customer preferences for PLS or mark-up contracts). However, if Khan does not limit

his analysis to supply sides factors, he does not offer a strong explanation based on demand

factors: the main idea of his article is the evolution of the entrepreneurs risk aversion during

the life of the company. Indeed, he considers that entrepreneurs have a high risk aversion

when they create and launch their business and this risk aversion decreases gradually during

the life of the company. Thus, new entrepreneurs are expected to prefer the use of PLS

contracts, while experienced entrepreneurs prefer mark-up contracts. In other words, Khan

encourages the IFIs to provide PLS contracts to the new entrepreneurs that have a high

aversion risk level.

Interested in the liabilities side of the IFIs, Chong and Liu (2009) underline another aspect of

the problem. So far, the issue is only around "PLS contracts vs. mark-up contracts" in the

assets of financial institutions, since the liability of an IFI cannot take, by definition, another

form than PLS. Indeed, the liability of an IFI contains four categories of funds: nonremunerated deposits, investment accounts, savings accounts and equity. Except the nonremunerated deposits of which the face value is guaranteed, the remuneration of the three

other classes of liabilities is based on the sharing of profits and losses.

7

The authors observe that the dominance of the mark-up contracts in the asset side transforms

the nature of liabilities to which the performance is linked. In addition to that, they note that

Islamic banks determine their profit margin for mark-up contracts by referring to interest rates

such as LIBOR. Thus, for the authors, these two facts explain that Islamic finance industry

has lost its original participatory nature. Indeed, being given that the performance of the

liabilities is backed to the performance of the asset class, which is evaluated by the reference

to the interest rate since the mark-ups contract are dominant in this side, the liability class

(legally Mudharaba) have not the characteristics of PLSs anymore. Its performance is

correlated with the rate of interest such as conventional bank.

This situation reveals how the determination of the mark-up, based on interbank interest rates,

disrupts the functioning of Islamic financial industry and underlines the necessity and the

importance of an endogenous profit margin theory for those contracts.

III- An Alternative Explanation: the Significance of the Demand’s Factors.

The proofs put forward by the mainstream literature are not sufficient to explain the current

use of PLS contracts by Islamic banks, because they are essentially based on an asymmetric

information approach.

Khan (1995) is the only author who attempted to take into account demand factors in his

argumentation. Despite the importance of his contribution, through the temporal

differentiation of entrepreneurs risk profiles, his theory is unable to explain the banishment of

the PLS contracts but, it explains well their non-exclusive use in a Sharia-compliant

financing.

In fact, the use of PLS financing methods depends on both the structural calculation of the

mark-up contracts profit margin and the underlying risks for each one of these two contracts.

At this stage of the reasoning, we must postulate that taking into account the risks related to a

contract cannot stop the borrower from holding it. It only depends on the remuneration of the

8

contract, which must include the risks born by the lender. This postulate is inconsistent with

the survey results of Habib and Khan (2002), who found that the risk allocation provided

within the PLS contracts, leads to their marginalization, instead of generating earnings

changes. In other words, the substitution of PLS financing in favor of mark-up contract is,

first and foremost, a question of prices and market adjustment; the current methods used by

the Islamic financial industry to determine the profit margins are detrimental to the PLS

contracts.

According to the previous developments, we can now shape a feature of the Islamic banking

comparatively to the conventional banking system. While the conventional banks provide one

type of contract, with a predetermined and fixed remuneration (interest rate), Islamic banks

are bi-contractual, they offer to their customers the choice between two main categories of

financial contracts: PLS and mark-up. The question of the margin profit determination for the

last type of contracts remains without any theoretical answer in the literature.

This paper aims to find out a theoretical approach to the profit margin calculation method for

the markup category, in order to maintain the two categories of contracts available in the

market. The sine-qua-non condition of this achievement is to equalize the profit of the two

risks adjusted type of contracts.

Obviously, one of the two contracts is doomed to disappear, if one of them is more profitable

than the other. The reasoning of the IFI client is simple: he must choose between the contracts

available on the market, according to his share in the profits once the funds provider is paid.

For a given sharing profit ratio and a certain level of expected profit, PLS contracts become

more attractive for the borrower than the mark-up contracts.

By setting the Murabaha margin without taking into account the project’s expected returns,

the IFI divides its potential customers into two categories: the first category includes

9

entrepreneurs, who expect high returns for their projects and are interested in the mark-up

contracts because they do not want to share the high level of expected profit with the IFI.

The second category includes those expecting relatively low yield for their projects and then

preferring the PLS financing. This being said, when the Islamic banks refuse to provide PLS

contracts for reasons based on adverse selection and/or excessive risks, this affect only the

second category of customers, since the first clients category has been pushed aside by the

current way of calculating the margin profit in the mark-up contracts. Actually, Islamic banks

refuse to provide PLS contracts but only for some of its customers and not all of them. The

ones who want to subscribe to this type of contracts assess themselves as bad quality clients.

This fact explains the results of the survey conducted by Habib and Khan (2002). The IFI

managers perceive a lack of supply of PLS contracts for some of their customers as

concerning all of them. Finally, the predetermination of the mark-up creates what we call

“artificial adverse selection”: in the framework of the exogenous determination of the markup model, the demand of the PLS contract is a signal of poor quality.

Asymmetric information theories put forward by the mainstream literature hide an implicit

assumption about the contractual choice power: considering that the lack of PLS contracts

comes from the supply side in the market, the literature gives this contractual choice

exclusively to the bank. However, nothing can support this position under the assumption of a

reasonable banking competition, which is the case in most countries where Sharia-compliant

finance exists. Indeed, a sufficient number of IFIs, operating in a given economy, gives the

choice to the entrepreneurs to determine the appropriate contractual form to finance their

projects: the IFIs cannot, in principle, refuse any kind of financing contract, while the price

(the profit margin) of this contract takes into account the underlying risks.

However, the structures of the IFIs balance sheets show a mitigated use of PLS contracts.

Assuming that the level of bank competition is sufficient, this situation must have another

10

reason. In order to explain this lack of PLS contracts, a plausible research way is to look at the

demand side and assume that the customers are the ones who refuse the PLS contract, for a

given quality of their projects. The PLS contracts, including Mudharaba, becomes more

profitable to the client if the performance of the project reaches a given excepted profit level.

IV- The Murabaha Profit Margin

A Sharia compliant financial system, as mentioned above, provides to the economic agent the

choice between two categories of contracts: PLS contracts and Mark-up contracts. To

simulate this situation in a model, we must define first, the conditions under which we avoid

artificial adverse selection problems. To do this, we set up the following assumptions:

A1: To finance his project, an entrepreneur has only the choice between two types of

contracts: Murabaha (mark-up) and Mudharaba (PLS);

A2: An entrepreneur will always choose the contract maximizing the utility of his share in the

expected profits of the project;

A3: The repayments of the debt and profits distribution are always done at the end of the first

and unique period. At this date, the value of the financed asset is assumed to be null.

A4: In the financing operations, the stakeholders – entrepreneurs and funds providers - are

risk neutral. This is a temporary assumption that will be changed later on.

A5: The profit sharing ratio is an exogenous variable

A6: The Mudharaba contract is drawn up in such a way that it is more attractive for the

entrepreneur to reveal his real results than hide them.

The Model

According to A2, the entrepreneur chooses between the two contracts supplied by the Islamic

bank. His choice will depend on the expected profit utility for each one of them. Entrepreneur

utility for Mudharaba and Murabaha contracts could be written down as follows:

11

+

π

{

𝑀𝑢𝑑𝑎𝑟𝑎𝑏𝑎 = 𝑈 [(1−∝) ( − 1) ]

𝐼

(1)

𝜋

𝑀𝑢𝑟𝑎𝑏𝑎ℎ𝑎 = 𝑈 [( − 1) − 𝛿]

𝐼

Where: 𝑈(𝑊) Utility of an agent for a random Wealth (𝑊).

is the share of the profit due to the owners of capital in a Mudharaba contract;

∝

I

is the initial investment made (I = 0 at the end of the production cycle)

𝛿

is the Murabaha profit margin for the IFI, and is expressed in relative terms, that are to

say, it represents a share of the initial investment I ;

𝜋

+

𝜋

( − 1) = 𝑚𝑎𝑥 ( − 1, 0)

𝐼

𝐼

;

Furthermore, the assumption of risk neutral agents’ behavior allows us to write down the

following expected value of the profit utility: 𝑈(𝑊) = 𝐸(𝑊). The entrepreneur gains, for the

two contracts, as expressed by relation (1), can be rewritten as follows:

π

{

+

𝑀𝑢𝑑ℎ𝑎𝑟𝑎𝑏𝑎 = 𝐸 [(1−∝) ( − 1) ]

𝐼

𝜋

(2)

𝑀𝑢𝑟𝑎𝑏𝑎ℎ𝑎 = 𝐸 [( − 1) − 𝛿]

𝐼

Where E (π) is the expected value of the raw profit of the project (with E (π) ≥ 0);

In a Mudharaba contract, the entrepreneur shares the gain with the funds provider: (1−∝) is

the net share of the funds provider and (∝) the share of the project manager or entrepreneur. In

case of failure, the fund provider loses the total amount of money brought to the project and

the entrepreneur takes on the time and efforts devoted to the project. Moreover, in a Murabaha

contract, the entrepreneur commits himself to pay to the IFI, in return for the purchasing of

the investment machine, the purchase price of the machine plus a profit margin(𝛿). In the

contract, the profit margin (𝛿) can be worked out independently from E(π) but the choice that

the entrepreneur has to do between the Murabaha and the Mudharaba contracts, requires a

calculation where the two profit margin must be similar. This leads us to say that the

determination of the profit margin impacts significantly the market equilibrium.

12

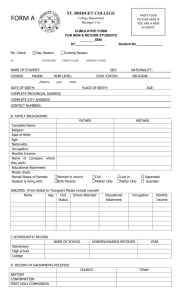

For illustration purpose, let us assume that the Murabaha profit margin (𝛿) is exogenously

determined, which represents the Islamic finance industry in ongoing practice. Let us also

assume that 𝛿 = 12 and ∝= 0,6. We observe that the results of this simulation are not linked to

the chosen value for ∝ and ; it is shown in Appendix 1 that the value change of the two

parameters impacts the switching equilibrium point between the contracts but not the

fundamental result. The following chart shows the expected value of the entrepreneur profit

for each contract, as expressed in equation (2), in the framework of an exogenous profit

margin determination.

Profil des gains: Moudharaba vs. Mourabaha

3.5

3

2.5

2

Gains

1.5

1

Point Thêta

0.5

0

-0.5

Moudharaba

Mourabaha

-1

-1.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

Profit net

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

This illustration shows that the entrepreneur would have three different areas of gain. The first

area covers the cases where the project does not generate enough cash flow to cover the initial

investment cost I, while the second case corresponds to the case where the net profit of the

project is positive without reaching the level Ө. In these two areas the entrepreneur must use

the Mudharaba contract since it always provides a gain equal or greater than what he would

get by choosing a Murabaha contract. The third area corresponds to scenarios where the net

profit of the project is higher than the point Ө: in this area the choice of Murabaha seems

more profitable for the entrepreneur. This demonstration remains valid with a multitude of

entrepreneurs: the members of the first two areas seek PLS contracts while the best

entrepreneurs, members of the third area, seek mark-up contracts.

13

Proposition 1: There is an Artificial Adverse Selection involved by the exogenous

determination of the Murabaha profit margin. This factor explains, for the most part, the low

level of PLS contracts in Islamic finance industry.

This being given, the only situation where Mudharaba and Murabaha have the same

satisfaction level occurs when the net expected gain for both contracts is the same. This could

be written as follows:

(2)

⇔

𝜋

+

𝜋

(1−∝)𝐸 [( − 1) ] = 𝐸 ( − 1) − 𝛿

𝐼

𝐼

𝜋

𝜋

𝐼

𝐼

+

𝛿 = [𝐸 ( − 1) − (1−∝)𝐸 [( − 1) ]]

(3)

The calculation of δ with these parameters restores the equilibrium in the market, and also

ensures the existence of the two contracts by eradicating the sources of the artificial adverse

selection. Here, the profit margin of the Murabaha is endogenously determined, which is

basically different from the current exogenous pricing way of the Islamic banks. The margin

profit is an increasing function of the expected value of the profit E (π) and of the fund

provider profit share (α). This means that the determination of the Murabaha profit margin is

not a matter of setting a benchmark like the interbank interest rate of the conventional

financial system.

Our calculation method of (δ) shows the way to determine the share due to the fund provider,

in the value added creation process, and at the same time, it underlines the principle of sharing

profits and losses, which is supposed to be a strong feature of the Islamic finance for all types

of Sharia-compliant contracts. By using this calculation method, the IFI determines a specific

profit margin for each project, or at least, for each sector, which is most plausible. Moreover,

the IFI must assess the profit margin until his client derives the same satisfaction from the

Murabaha or Mudharaba contracts; this means that he becomes indifferent with regard to any

of these contracts. Lastly, the IFI must also take into account the specific risk underlying each

contract.

14

Economic Agents Risk Aversion

Previously, we assumed a risk neutral behavior of all stakeholders in order to be compliant

with A4. From now on, we assume that economic agents are risk averse; and we assume that

the entrepreneur choices are expressed with the following entropic utility function:

𝑈𝐸 (𝑊) = − γ𝐸 ln E [𝑒𝑥𝑝 (−

1

γ𝐸

𝑊)]

(4)

where 𝑊 is the random wealth of the entrepreneur.

Relation (1) allows us to express the market equilibrium as follow:

+

π

𝜋

𝑈𝐸 [(1−∝) ( − 1) ] = 𝑈𝐸 [( − 1) − 𝛿]

𝐼

𝐼

The entropic utility function is characterized, amongst others, by its cash-invariance, which

gives us the following formula:

𝜋

𝜋

𝑈𝐸 [( − 1) − 𝛿] = 𝑈𝐸 [( − 1)] − 𝛿

𝐼

𝐼

Then, the equilibrium condition can be rewritten as follows:

𝜋

π

𝐼

𝐼

+

𝛿 = 𝑈𝐸 [ − 1] − 𝑈𝐸 [(1−∝) ( − 1) ]

(5)

What the entrepreneur could pay for a Murabaha contract is equal to his disutility of what he

would pay for a Mudharaba contract, which is[𝛼 (𝜋𝐼 − 1) ⥣{𝜋−1≥0} + (𝜋𝐼 − 1) ⥣{𝜋−1<0}].

𝐼

Where ⥣{𝜋−1≥0} = { 1

𝐼

𝑂

𝑖𝑓

𝜋

𝐼

𝐼

−1≥0

𝑜𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑤𝑖𝑠𝑒

It is interesting to highlight the subjective dimension of the profit margin: the entrepreneur

does not compare monetary amounts, but he compares a monetary amount (𝛿) with his own

disutility for the IFI share, in the Mudharaba contract: [𝑈𝐸 [𝜋𝐼 − 1] −

π

+

𝑈 [(1−∝) ( − 1) ]].

𝐼

This subjective dimension (Utility/disutility), expressed through the risk aversion/ appetite,

marks out the difference between the Murabaha profit margin and the interest rate of a

conventional loan: the Murabaha profit margin depends on the risk aversion of the

entrepreneur, beyond the expected profit. Thus, the calculation of the profit margin has a

15

double dimension: the first one is the economic activity sector, because of the expected

profitability depends on the sector growth, for the most part. The second one is personal and

depends on the entrepreneur risk aversion.

Being given that, entrepreneur preferences can be described by an entropic utility function;

the Murabaha profit margin in equation (5) can then be rewritten as follows:

𝛿 = [− γ𝐸 𝑙𝑛 𝐸 [𝑒𝑥𝑝 (−

1

γ𝐸

(𝑍 − 1))] + γ𝐸 𝑙𝑛 𝐸 [ 𝑒𝑥𝑝 (−

1−∝

γ𝐸

(𝑍 − 1)+ )]]

(6)

where: 𝑍 = 𝜋𝐼

𝜋

We also assume that the raw profit of the project 𝑍 = 𝐼 , follows a Gamma distribution with

two parameters 𝜃 and k (where 𝜃 and k are strictly positive real numbers). And we know that

the probability density function of a Gamma distribution is given by:

𝑥

𝑥 𝑘−1 𝑒 𝜃

𝑓𝑍 (𝑥) =

Γ(𝑘 )θ𝑘

Then, we can rewrite the Mudharaba margin profit as follows (see Appendix 2):

𝛿 = [−1 + 𝛾𝐸 𝑘 ln (1 +

θ

𝛾𝐸

) +𝛾𝐸 ln (1 −

1

Γ(𝑘 )

1

1

𝜃

(1−α)θ 𝑘

Γ(𝑘 )(1+

)

𝛾𝐸

Γ( ,𝑘 ) +

1

(1−α)

𝜃

𝛾𝐸

Γ( +

, 𝑘 ))]

(7)

This equation shows that the profit margin depends on:

The appetite/ aversion for the risk,

The Mudharaba profit sharing ratio

The two random variable parameters ( and𝑘), representing the project expected profit.

A profit margin simulation, based on the first two parameters, shows the following curves.

We observe that the profit margin is an increasing function of the appetite for risk of the

entrepreneur γ𝐸 and the Mudharaba profits sharing ratio.

16

The Murabaha Default Risk

A fundamental component of the Murabaha contract has been deliberately omitted: as

mentioned above, the entrepreneur honors to the IFI an amount of (𝐼 + 𝛿) at the end of the

production cycle. Nonetheless, this can be done for sure only in certain framework. In a risky

environment, a default can occur and the provider funds profits must be rewritten as follows:

+

−

𝜋

𝜋

𝑀𝑢𝑑ℎ𝑎𝑟𝑎𝑏𝑎𝐼𝐹𝐼 = 𝑈𝐼𝐹𝐼 [𝛼 ( − 1) − ( − 1) ]

𝐼

𝐼

{

𝛿

𝜋

𝑀𝑢𝑟𝑎𝑏𝑎ℎ𝑎𝐼𝐹𝐼 = 𝑈𝐼𝐹𝐼 [ ⥣{𝜋≥(1+𝛿)𝐼} + ( − 1) ⥣{𝜋<(1+𝛿)𝐼} ]

𝐼

𝐼

𝜋

𝜋

−

Where (𝜋𝐼 − 1) = { 𝐼 − 1 𝑠𝑖 𝐼 − 1 < 0

𝑂

𝑂𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑤𝑖𝑠𝑒

Thus, the equalization of the fund provider profits, for the two contracts, gives us the new

formula of IFI profit margin (𝛿). Even if the margin was previously obtained by

entrepreneur’s preferences, the uniqueness of δ can be deduced by equalizing the preference

of the fund providers. We can therefore write:

𝐸 𝑒𝑥𝑝 [−

+

1

𝜋

𝜋

1 𝛿

𝜋

(𝛼 ( − 1) + ( − 1) ⥣{𝜋−1≤0} )] = 𝐸 𝑒𝑥𝑝 [−

( ⥣𝜋

+ ( − 1) ⥣{𝜋−1<𝛿} )]

γ𝐼𝐹𝐼

𝐼

𝐼

γ𝐼𝐹𝐼 𝐼 { 𝐼 −1≥𝛿}

𝐼

𝐼

𝐼

This equation expresses the value of the margin δ that is function of itself. Indeed, the

introduction of the potential default of the borrower requires to take into account, ex-ante, in

the profit margin calculation method that, ex-post, the project could not generate enough cash

17

flow to cover the commitment at the end of the production cycle (I + δ). Mathematically, this

means that there can be no explicit solution for (δ): the margin of the Murabaha contract in

the presence of probability of default has to be done digitally. Nevertheless, we can make

some rearrangements of the above equation which is useful for the interpretation of the

determinants (δ) (see Appendix 3):

+

𝜋

𝜋

𝛿

𝜋

𝑈𝐼𝐹𝐼 (𝛼 ( − 1) + ( − 1) ⥣{𝜋−1≤0} ) ≤ 𝐸 [( ⥣{𝜋−1≥𝛿} + ( − 1) ⥣{𝜋−1<𝛿} )]

𝐼

𝐼

𝐼

𝐼

𝐼

𝐼

𝐼

𝛿

𝐼

≥

1

𝜋

𝐼

𝑃( −1≥𝛿)

𝜋

+

𝜋

𝜋

[𝑈𝐼𝐹𝐼 (𝛼 ( − 1) + ( − 1) ⥣{𝜋−1≤0} ) − 𝐸 (( − 1) ⥣{𝜋−1<𝛿} )]

𝐼

𝐼

𝐼

𝐼

(8)

𝐼

Moreover, the entrepreneur, under Murabaha contract, can provide guarantees to the Islamic

bank in case he could not honor its commitments. These guarantees cannot, in principle, be

used by the bank if the borrower is in good faith and if he did not have misconduct, even in

case of failure. Thus, when collaterals are engaged in the contracts, the risk for the bank

decreases and the Murabaha profit margin also goes down. This is due to the fact that the

calculation of the margin is done with the same method, with or without guarantees. Indeed,

providing a guarantee for the total loan amount is equivalent to consider that the borrower

will never fail. Thus, the profit margin, even with guarantees, is still written as equation (6)

shows:

𝛿 = I −1 + 𝛾𝐸 𝑘 ln (1 +

θ

1

1

) +𝛾𝐸 ln 1 −

Γ( ,𝑘 ) +

𝛾𝐸

Γ(𝑘 ) 𝜃

[

(

1

1 (1 − α)

Γ( +

,𝑘 )

(1 − α)θ

𝜃

𝛾𝐸

Γ(𝑘 ) (1 +

)

𝛾𝐸

)]

Proposition 2 : The coexistence of the two types of contracts in the market can occur only if 𝛿

is a function of the sharing profit ratio, the probability of default of the contract and the risk

aversion of the entrepreneur. These parameters are the determinants of the cost of money in a

Sharia compliant economy.

18

V- Conclusion

This paper suggests a new explanation to the low presence of Profit and loss share (PLS)

contracts in Islamic banks balance Sheets. According to the model we have developed, this

issue is due to the calculation method of the profit margin used by Islamic financial

institutions for mark-up contracts. Then, we propose an alternative method based on the

equalization of the financing cost for the two major categories of contracts in Islamic Finance

Industry. Using this approach, we avoid artificial adverse selection that results from the

exogenous determination of the margin in the mark-up contracts. Indeed, in the case of an

endogenous determination of the Murabaha profit, the function of this margin depends on the

sharing profit ratio, the default probability of the contract and the risk aversion of the

entrepreneur.

Moreover, while the pricing of a conventional loan is based on an only interest rate, common

to the whole economy, the profit margin of a Murabaha contract integrates the specificities of

the economic sector of the project with the entrepreneur risk profile.

19

Bibliography

Abalkhail Mohammad and Presley John : How informal risk capital investors manage

asymmetric information in profit/loss sharing In Islamic Banking and Finance: New

perspectives on profit-sharing and risk (2002).

Aggarwal Rajash and Youcef Tarik : Islamic Banks and Investment Financing. Journal of

Money, Credit and Banking. Vol 32, n 1. (2000).

Ahmed Habib: Incentive compatible profit-sharing contracts : a theoretical treatment. In

Islamic Banking and Finance: New perspectives on profit-sharing and risk (2002).

Al-Suwailem Sami: Optimal Sharing Contracts. Presented at the Fifth International

Conference on Islamic Economics and Finance (2003).

Chong Beng Soon and Liu Ming Hua: Islamic banking: Interest-free or interest-based ?

Pcific-Basin Finance Journal 17 (2009).

Dar Humayon et Presley John : Lack of Profit Loss Sharing in Islamic Banking management

and Control Imbalances. Economic Research Paper No 00/24. Loughborough University

(2001).

Haque Nadeem and Mirakhor Abbas: Optimal Profit-Sharing Contracts and Investment in an

Interest-Free Islamic Economy. International Monetary Fund, Working Paper (1986).

Jouaber Kaouther and Mehri Meryem : A Theory of Sharing Ratio under Adverse Selection:

The Case of Islamic Venture Capital. Presented at the workshop: International Sustainable

Finance Paris-Dauphine University (September 2011).

Khalil Abdel-Fattah, Rickwood Colin and Murinde Victor: Evidence on agency-contractual

problems in mudarabah financing operations by Islamic banks. In Islamic Banking and

Finance New perspectives on profit-sharing and risk (2002).

Khan Tariqullah: Demande for and supply of mark-up and PLS funds in Islamic banking.

Islamic Development Bank: IRTI (1995).

20

Khan Tariqullah et Habib Ahmed: Gestion des risques analyse de certains aspects liés à

l’industrie de la finance islamique. Banque Islamique de Développement : IRTI (2002).

Nienhaus Volker: Prifitability of Islamic PLS Banks Competing with Interest Banks:

Problems and Prospects. Journal of Research in Islamic Economics. Vol 1, (1983).

Presley John and Sessions John: Islamic Economics The Emergence of a New Paradigm. The

Economic Journal, Vol 104, No 424 (1994).

Tag-El-Din Seif: Income Ratio, Risk-Sharing and the Optimality of Mudarabah. Journal of

King Abdulaziz University: Islamic Economics. Vol 21-2 (2008).

Yasseri Ali Islmic banking contracts as enforced in Iran. In Islamic Banking and Finance New

perspectives on profit-sharing and risk (2002).

21