Becoming a Mentor - Keele University

advertisement

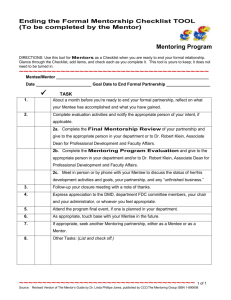

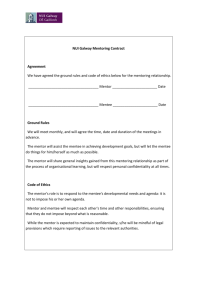

Becoming a Mentor What is a mentor? A mentor is someone who can help their mentee through an important transition in: Learning: helping them to acquire knowledge, skills and understanding Coping or coming to terms with a difficult or new situation, for example induction, integration into the organisation or a new role Resolving a problem or issue Career development, including advice on personal skills, image and profile Personal growth: increasing confidence through helping them to take responsibility for themselves, their careers and their own development. The relationship between a mentor and mentee should be personal and confidential, and is different and distinct from a relationship between a superior and subordinate. A mentor is someone who: Cares about the mentee and their growth and development Provides insights into the learner’s situation and helps the mentee make the most of that situation and avoid pitfalls Is prepared to share knowledge and experience that is of use to the learner – without suggesting theirs is the right way to do something Accepts the mentee as an individual, with their own personality, strengths and weaknesses Recognises their status as an equal in the mentoring relationship, even if there is a different relationship in the day to day hierarchy outside the mentoring process. Through the mentoring relationship a mentor is helping someone to raise their own self-awareness, think about what they consider to be important and to focus on the future. Mentors challenge and support mentees as appropriate, and will help mentees take control of and responsibility for their lives. A good mentor will want to ensure that the mentee gains confidence and independence as a result of mentoring, and is able to go forward independently from the relationship. “Mentoring involves primarily listening with empathy, sharing experience (usually mutually), professional friendship, developing insight through reflection, being a sounding board, encouraging.” David Clutterbuck Mentoring provides development opportunities for mentors, and can bring great personal satisfaction. Being a mentor can improve leadership skills and provides the 1 opportunity to learn from different approaches and different ways of thinking. It can be challenging, inspiring and enlightening. The mentoring relationship The nature of the mentoring relationship will vary according to the people involved, the purpose of the mentoring, and the particular mentoring context. Contextual factors that impact on the nature of the mentoring relationship include: How formal the mentoring arrangements are The difference in age, experience, ability and influence of the mentor and mentee The length of the relationship The level of rapport between the mentor and mentee The particular level and type of support that the mentor can offer and the mentee requires The degree of commitment by both mentee and mentor to achieving change through the mentoring partnership Research suggests that certain factors seem to be present across the spectrum of effective mentoring relationships. Building and maintaining effective mentoring relationships works best when there is: Clarity of purpose: The mentee needs to have specific and or / individual learning objectives – something they wish to achieve or resolve or an outcome they aspire to. Rapport: Alignment of values between mentor and mentee can help to build and sustain the relationship. But it is useful to recognise that challenge and difference in perspective may be lacking if values are too well aligned. The ability to build rapport encompasses the ability to accept and value difference. Role and role boundaries: Understanding the role of the mentor helps to ensure that appropriate behaviour is used. Mentors need to know the boundary of the mentoring role - and when to refer a mentee on if they require support that is outside of the role of developmental mentoring. Voluntary: The relationship will work best when both mentor and mentee want to be there. Competence: Both the mentor and the mentee need to bring some skills and attributes to the relationship – communication skills to articulate ideas and issues, the ability to listen and to challenge constructively, the ability to be honest both with themself and the 2 mentee, to reflect on what is said during and beyond the dialogue, and to demonstrate empathy. Behaviour: The more directive the mentor behaviour, and the more passive the behaviour of the mentee, the less successful the mentoring relationship will be. Review: The mentor and mentee should take time to review the relationship – this increases openness and commitment and provides opportunities to enhance the mentoring relationship. Evaluation: Evaluation is used as a stimulus for the mentor and mentee to examine what they are doing and what they have learned. The expectations and behaviour of both the mentee and the mentor will evolve throughout the relationship and as a consequence of the mentoring interaction and thus the nature of the relationship will change and develop over the duration of the mentoring arrangement. The mentoring timeframe Mentoring relationships, while varying in duration, tend to move through a number of ‘phases’ as they mature. This is sometimes depicted as the three stages illustrated below. A period when the relationship begins, rapport is developed, ‘trust’ is developed and a shared understanding of the general purpose and the parameters of the relationship are established The relationship becomes more purposeful and has a clearer sense of direction A period when the relationship draws to a close and either ends or shifts to a friendship / supportive colleague relationship A measure of the quality and effectiveness of the mentoring relationship is the management of each stage of the relationship and of the transition between stages. 3 Megginson et al 2006 suggest that more formal developmental mentoring schemes supported by the organisation tend to follow five stages, as outlined below. 1. Build Rapport The mentor and mentee explore whether they are able to work together. Developing rapport depends upon: How the mentor and mentee perceive alignment of their personal values the level of mutual respect developing a shared understanding of the broad objectives of the relationship reaching mutual agreement about the roles and behaviour appropriate to the mentoring relationship – and setting this out in the form of a relationship agreement or contract. Rapport is achieved through dialogue – “an open exchange that relaxes the typical barriers between comparative strangers. If rapport does not occur it is incumbent on both parties to explore the issue, rather than pretend it does not exist.” ( Megginson et al 2006). As a result the mentor and mentee may decide not to move forward with the relationship – or alternatively go with it if they decide there is valuable learning potential from working with someone different. 2. Setting Direction During this stage the mentor and mentee: clarify and refine what the mentoring relationship should achieve for both the mentee and the mentor link medium and long-term goals to the day to day context continue to build rapport as the mentor and mentee explore responses to the issues raised. 3. Progression This ‘making progress’ stage typically lasts longer than the first two stages. The mentor and mentee: Are comfortable with challenging each other’s perceptions Explore issues more deeply Experience mutual learning The mentee assumes more of the lead in managing the relationship and the mentoring process. 4. Winding up This occurs when the mentee: 4 has achieved a large part of his or her goals feels equipped with plans, insights and confidence to continue the journey alone. Continuing the mentoring relationship beyond this point can result in dependency or counter-dependency - both unhealthy scenarios. Managing how the relationship ends is also an important consideration. “….planning for a good ending is critical if both parties are to emerge from the relationship with a positive perception of the experience…reviewing and celebrating what has been achieved is… more effective than winding down (drifting apart).” (Megginson et al, 2006) 5. Moving On This is the stage where mentor and mentee move on. The relationship may be reformed into friendship. An indication of the relative time that a mentoring relationship may progress through the five stages is shown below. The time line also depicts the development of the relationship to a point of maximum learning and added value and beyond. Intensity of learning and value added 1 2 3 4 Source: Megginson et al 2006 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 5 Time Key Building rapport Setting direction Progression Winding up Moving on An effective mentor will be monitoring and reflecting on the overall mentoring journey and will recognise when transition between stages is happening or needs to be managed. Each individual mentoring meeting is also a ‘journey’ and the mentor is supporting each conversation with an appropriate ‘process’ or ‘structure’. 5 The mentoring process The purpose of the mentoring process is to create an environment in which the mentee can reflect on and address issues related to management of situations and relationships, and issues of career and personal development. A learning conversation can be seen to have a number of components – reaffirmation, issue identification, building mutual understanding, exploring potential solutions and final check or summary. A number of models have been developed by experienced practitioners to give shape to a mentoring session. Information about some of these different models is available on the Mentoring website as separate documents within: Tools for effective mentoring A 3-stage model of the mentoring process The 5 Cs Model of Mentoring The 7Cs Model of Mentoring Using the Learning Cycle to facilitate learning in Mentoring The information for each model highlights when the approach would be useful, explains the different components of the approach and suggests dialogue and questions that are appropriate to the different elements of the mentoring conversation. There is no one best model – and different models lend themselves to different kinds of mentoring conversations. As a mentor it can be helpful to become familiar with different approaches to enhance the range of ways in which you can respond to the needs of the mentee. What are the attributes of an effective mentor? From the perspective of the mentee, the following attributes have been identified as contributing to effective mentoring relationships. The mentor: Is someone who is respected and trusted by the mentee to maintain personal and professional confidentiality Listens without judgement or criticism and reflects on what is being said Is someone who is interested in and prepared to invest time in the mentee Is someone who is knowledgeable and open, and prepared to share their own experiences Challenges, offers advice – but does not give advice 6 Is someone who encourages, and while they can be critical, is always positive/constructive Has a positive and realistic outlook. The key to good mentoring is being able to listen actively to the mentee and to offer advice if requested – but not telling the mentee what to do. It is the mentee who should make decisions, not the mentor. A mentor can help a mentee to: Understand behaviour appropriate to a particular situation or context Understand the workings of the institution Acquire an open flexible attitude to learning Understand different and conflicting ideas Be aware of institutional politics Overcome setbacks and obstacles Acquire technical expertise Gain knowledge and skills Develop personally Adjust to change Reflect on personal values Getting started as a Mentor: Mentoring is a common, often unrecognised, helping activity. Effective mentoring requires certain personal qualities and skills. How will you know that you are ready to be a mentor? You can address this in a number of different ways. You can: Recognise and reflect on mentoring you do already Talk to other mentors Talk to people you have already mentored for feedback Consider the differences between mentoring and other learning and leadership roles and activities Consider the differences between mentoring and other ways of helping eg. coaching, appraisal, counselling Reflect on your own experience of being a mentee. You can also address this question by thinking about your attributes using the list below. Do you have: A range of experience A variety of context based skills A sense of commitment to the institution, its values and vision 7 Good listening skills Well-developed interpersonal skills An ability to relate well with people who want to learn An interest in helping and developing others An open, flexible mind, and a flexible attitude, Do you recognise your own need for support? Time and willingness to develop relationships with mentees? If you have these attributes then you are ready to mentor! Developing as a mentor The mentoring role is very rewarding – and provides opportunity for significant learning for the mentor. Mentors often need to deepen their own personal development if they are going to be able to meet the needs of a range of mentees in a flexible and learner-centred way. Whether as part of more formal support or self-managed development, mentors can reflect, review and record to enhance their development and growth as a mentor. Reflection is crucial for: Remembering what occurred Considering one’s own and mentee’s actions and reaction Highlighting areas for planning and acting for both mentor and mentee. Review is about: Making sense of the meeting when out of the bustle of the session itself Planning what to do next time the pair meet Opening oneself up to the views of others (the mentee, supervisors or fellow mentors). Recording is not so universally practised, but writing down thoughts about meetings: Allows for a deep reflection on process In itself leads to new insights and choices in a way that simply thinking about the relationship does not Provides raw material for supervision and accreditation. Resources: The pro-forma in Appendix One provides a basic template that may be used to support the mentoring relationship. The form can be used to: Undertake some initial thinking before you start a mentoring relationship 8 prepare for individual mentoring sessions capture actions from mentoring sessions review the progress of a mentoring relationship. Appendix Two provides a checklist that you can use periodically with your mentee to review how the mentoring relationship is working. References: Alred, G., Garvey, B., Smith, R., Mentoring Pocketbook, 2 nd Edition, 2006, Management Pocketbooks Ltd. Daloz, L.A., Mentor – Guiding the Journey of Adult Learners, 2nd Edition, 1998, Jossey-Bass Inc. Megginson, D., Clutterbuck, D., Garvey, B., Stokes, P., Mentoring in Action, 2 nd Edition, 2006, Kogan Page Ltd. Pegg, M.,The Art of Mentoring, 2003, Management Books 2000 Ltd. 9 10 Appendix One Mentoring meeting pro forma Date of meeting: Objectives of the meeting: What do you hope to achieve. Why are you having the meeting? Agenda: What are you going to discuss? Action Plan: (including by whom and when) Date, time and place of next meeting: Feedback: What has gone well in the meeting / is going well in the mentoring. What are you benefitting from, what do you find useful? What would make it even better? 11 12 Appendix Two Mentoring Phases Checklist This is a useful checklist for the mentor and mentee to use periodically in order to step back and look at how the mentoring relationship is working and what stage it has reached. It is particularly useful if the mentor and mentee share their views and openly discuss areas of disparity. Strongly Agree Building Rapport We have established a good understanding of each other I feel relaxed in our meetings We understand and respect each other’s views and feelings We respect the confidences we share I feel confident in the relationship Direction Setting We have established clear goals for the relationship We have agreed the objectives, a broad route towards them and ways of measuring progress We are beginning to surface differences of opinion and to work through them constructively The mentee is comfortable challenging the mentor Progress making The mentee is increasingly setting our meeting agenda Responsibility for managing the relationship is resting increasingly with the mentee We have celebrated achievement of goals and milestones We have a positive, supportive, nurturing relationship The mentee is much more confident to cope with new or demanding situations than when our relationship began Winding up / moving on We have largely achieved all the goals we set for our relationship The mentor can now tackle most situations confidently without the mentor’s help The mentee feels they have reached self-sufficiency 13 Agree Disagree Strongly Disagree 14