Stating your hypothesis/objective

advertisement

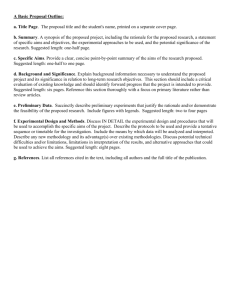

What makes a good grant? A good idea A good approach Good writing Pre-submission Planning Allow 3 months for conception and writing. Bounce your ideas off colleagues. Develop long-term objective and 5 year aims. Formulate strategy regarding other grants. Identify potential IRG. The Review Process Your grant arrives in Bethesda along with ~30,000 others. Then what? Your grant is scanned to a pdf format. Referral officers act as traffic cops. • Review group (CSR or IC) • Institute SRAs (Exec secs) work for CSR. Program Director’s work for Institutes. SRA assign’s reviewers to your grant. The Review Panel IRG (“Study Section”) is ~30 scientists + SRA. IRG members receive CD with all grants ~2 months before meeting. Usually 3 reviewers/grant, but may be more. Your reviewers receive paper copies of your grant. Reviewers share decisions regarding “triage,” critique and scores with IRG before meeting. IRG’s meet for 1-2 days, in Bethesda area. IRG’s review ~80 grants/meeting. Primary reviewer reads Description & critique. Secondary reviewers elaborate upon critique. You should check the composition of the IRG after your grant is assigned. Communicate with your Program Director after you have identified your IRG. THE FIVE REVIEW CRITERIA FOR NIH APPLICATIONS (As of 12-04) 1. SIGNIFICANCE Does this project address an important problem? If the aims are achieved, how will scientific knowledge or clinical practice be advanced? What will be the effect of these studies on the concepts, methods, technologies, treatments, or preventative interventions that drive this field? 2. APPROACH Are the methods appropriate to the aims? Does the applicant acknowledge potential problem areas and consider alternative tactics? Review criteria (cont) 3. INNOVATION Is the project original and innovative? Does the project challenge existing paradigms or introduce an innovative hypothesis in the field? Does the project develop or employ novel concepts or approaches for this area? (Novelty is less important if significance is high.) 4. INVESTIGATORS Are the experience and training of the PI and other researchers appropriate for the project? Does the investigative team bring complementary and integrated expertise to the project? Review criteria (cont) 5. ENVIRONMENT Does the environment in which the work will be done contribute to the probability of success? Do the proposed studies benefit from unique features of the scientific environment, or subject populations, or employ useful collaborative arrangements? Is there evidence of institutional support? Questions? Break Writing the Grant "I know some very great writers, writers you love who write beautifully and have made a great deal of money, and not one of them sits down routinely feeling wildly enthusiastic and confident. Not one of them writes elegant first drafts. All right, one of them does, but we do not like her very much. We do not think that she has a rich inner life or that God likes her or can even stand her.”…Anne Lamott Writing the Grant Follow instructions. (They change frequently.) Appearance matters! Be concise. Target the writing/content to the reviewers. Use correct grammar and spelling. Let it age, then reread and revise. Ask a colleague to critique both the science and the writing. Stating Your Objective The “Background and Significance” section should set the stage for your objective. Your objective (hypothesis) should be… • Recognizably significant • Experimentally tractable • Concisely stated Writing the Description The Description should be understandable by IRG members and should cover the points requested in the Instructions. The Description affects the trafficking of your grant. Be sure to distinguish between the long-term objective and the immediate aims. The most recent guidelines also ask for a 2-3 sentence summary of relevance to public health. You should write this as a short paragraph separated from the remainder of the Description. Writing the Specific Aims Limit to 3-5 aims per project period. State each aim in one sentence. Supplement each aim with a two or three sentence summary of approach. Each aim should… …be experimentally feasible. …have a realistic time frame. …have a definitive outcome. State as a question to be answered. Do not propose to “study” something. Help the reviewer explain to the IRG… …why the aim is important. …what is novel. …what is controversial. Specific Aims (see p 30) White space!!! “A grant in a page” encourages the reviewer to structure the review around this page. Writing the Preliminary Results/Progress Report Preface with a one page summary. Summarize major findings concisely. Document with references to publications. If not published, describe status. Detailed report should parallel the summary. A Progress Report Summary Your reviewer will begin his/her review with a summary of your preliminary results/progress. (see p22 and Ref. 27) A Progress Report Detailed report should parallel the Summary. Reference publications prominently! (27) Writing the Research Plan Organization of the research plan should parallel specific aims and be easy to follow. Document extensively with figures, etc. Demonstrate ability of PI to execute methods. Demonstrate awareness of problems. Include multiple (alternative) strategies. Provide chronology/time frame. The Research Plan Explain to the reviewer how the Research Plan is organized. Begin each section of the Research Design and Methods by reiterating the question. White space is an important part of the written grant! The Research Plan “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Figures should appear on the page where first cited. The Research Plan Alternative approaches increase the likelihood of success. Help the reviewer find information elsewhere in the grant. Bios, Resources, Co-PIs Collaborators, etc. Bio-sketch should emphasize training, experience and publications relevant to the proposed research. Resources should document the presence of all equipment, facilities, infra-structure essential to the proposed research. Pick co-PIs, collaborators, etc. with care and advanced discussion of expectations. The Most Common Mistakes SIGNIFICANCE AND INNOVATION Not significant or novel. Lack of compelling rationale for experiments. Incremental or low impact research. APPROACH Lack of clear, strong hypotheses or questions. Too ambitious. Unfocused aims, unclear goals. Too much unnecessary experimental detail. Not enough detail. Not enough preliminary data. Feasibility not shown. Correlative or descriptive data. Experiments not directed towards mechanisms. No discussion of alternative models/hypotheses. No discussion of potential pitfalls. Common Mistakes (cont.) INVESTIGATOR No demonstration of expertise. Low productivity. Needed collaborators not recruited. Letters from collaborators missing. ENVIRONMENT Little evidence of institutional support. Little or no start up package. Necessary equipment not available. In >20 years of reviewing, during which time I have seen >1000 RO1’s, the most common shortcoming I have seen has been poor writing, the result being it is difficult to discern what the applicant plans to do! Does and Don’ts of Communicating with the NIH Do not contact the SRA or any IRG member! Do contact your Program Director. Include a cover letter with your application. Responding to the Critique The reviewer is (almost) always right! If not, be tactful. Solicit input from your Program Director. The best response is results!!