General Argument from Evil Against the Existence of God

advertisement

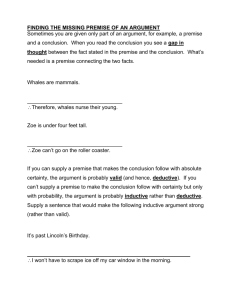

General Argument from Evil Against the Existence of God The argument that an all-powerful, allknowing, and perfectly good God would not allow any—or certain kinds of—evil or suffering to occur Two General Versions of the Problem • The logical problem (God’s existence is logically incompatible with the existence of evil) • The evidential/inductive/probabilistic problem (Some known facts about evil stand as evidence against the existence of God) Three Common Theistic Responses to the General Argument from Evil • • • Unknown Purpose Defense (UPD) Free Will Defense (FWD) Soul-Making Theodicy* (SMT) *Theodicy: is an attempt to resolve the evidential problem of evil by reconciling the traditional divine characteristics of omnibenevolence, omnipotence, and omniscience with the occurrence of evil or suffering in the world. Unlike a defense, which tries to demonstrate that God's existence is logically possible in the light of evil, a theodicy provides a framework which claims to make God's existence probable. Objections to Theist Defenses against Problem of Evil • Objection to UPD: “if you have no idea what reason God has for allowing evil, then for all you know there is no justifiable reason at all for an all-good God to permit it.” • Objection to FWD and SWT: “leaves much apparently gratuitous evil unexplained” Rowe’s Own Inductive Argument Against the Existence of God Some definitions: Narrow (a)theism: (dis)belief in the existence of an Omniscient, Omnipotent, Omnibenevolent Eternal Being Who Created the World [hereafter, GOD] Broad (a)theism: (dis)belief in the existence of some sort of divine being or reality Three Kinds of Atheism • Unfriendly Atheism • Indifferent Atheism • Friendly Atheism Rowe’s Argument • • • There exist instances of intense suffering which a GOD could have prevented without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse. A GOD would prevent the occurrence of any intense suffering it could, unless it could not do so without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse. Therefore: There does not exist a GOD. Things to notice about the argument • • It is valid (if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true) Given its validity, if we have rational grounds for believing the premises, we necessarily have rational grounds for believing the conclusion. But do we have rational grounds for believing the premises? • • • Consider the second premise: assuming that s is an instance of intense human or animal suffering which a GOD could prevent, let us ask what are the necessary conditions under which it would be the case that a GOD had failed to prevent s. Rowe states this necessary condition as a tripartite disjunction: Either (i) there is some greater good, G, such that G is obtainable by GOD only if God permits s, or (ii) there is some greater good, G, such that G is obtainable by GOD only if GOD permits either sor some evil equally bad or worse, or (iii) s is such that it is preventable by GOD only if GOD permits some evil equally bad or worse. • • Rowe’s then says that premise (2) of the Inductive Argument is true because on all three construals of its meaning, i.e., (i) or (ii) or (iii) above, if each is true, then (2) is true. Rowe concludes that premise (2) of IAEEG is true and accepted by theists and atheists alike. But then, is premise (1) of IAEEG is true? [There exist instances of intense suffering which a GOD could have prevented without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse ] • The Fawn Burned Alive in the Forest Fire CASE What is it about this case that suggests that (1) is true? Defending the Theist against the Inductive Argument for Atheism • The theist must attack the first premise of the argument. There are three ways to do that (see next slide) First Way • That the premise is defective in some way. PROBLEM: this can only be accomplished EITHER by arguing that the reasons supporting premise 1 are in themselves insufficient to justify accepting it, OR by arguing that there are other things we know which, conjoined with these reasons, do not justify us in accepting it. SINCE the argument is valid and Premise 2 is likely to be accepted by the Theist, this commits the Theist to the view that Premise 1 is actually false, not just that we lack a good reason to accept it. Second Way • Argue that the premise is FALSE. This can be accomplished in one of two ways: Direct Attack; Indirect Attack • Direct Attack: point out goods, e.g., to which suffering may well be connected which a GOD could not achieve without permitting suffering. PROBLEM: Rowe doubts this strategy can succeed due to lack of a way to establish that this is actually true in any particular case of suffering and any particular general good connected to it. – Indirect Attack: use the G.E. Moore Shift: • • • I do know that this pencil exists. If the skeptic’s principles are correct I cannot know of the existence of the pencil. Therefore: The skeptic’s principles (at least one) must be incorrect. How Shift Argument Works in General Suppose the following argument is valid: • P • Q • Therefore, R Attack that argument by posing the following counterargument: (1) not-R (2) Q (3) Therefore, not-P How the Shift Works Against the Inductive Argument: First, Remember the Inductive Argument (1) There exist instances of intense suffering which a GOD could have prevented without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse. (2) A GOD would prevent the occurrence of such intense suffering unless it could not do so without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse. (3) There does not exist a GOD. How the Shift Works Against Atheist Inductive Arg. – – – There exists an omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good being. (Denies #3 of the original Ind. Arg.) An omniscient, wholly good being would prevent the occurrence of any intense suffering it could, unless it could not do so without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse. (Repeats #2 of the original Ind. Arg.) Therefore, It is not the case that there exist instances of intense suffering which an omnipotent, omniscient being could have prevented without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse. (Denies #1 of Ind. Arg.) Conclusion: If this counterargument is sound, the theist has now offered rational grounds for rejecting (1), and thus the basic argument for atheism is unsound (since it has, by proving that its conclusion, which is the negation of the first premise of the atheist argument, proved that premise false, and thus the argument unsound). Result: STANDOFF!! First, why is this a standoff? Because the atheist accepts their argument, and so cannot accept the theist’s counterargument (each will accuse the other of begging the question with the first premise of each argument). What are the atheist’s options under these conditions? Rowe finds three: • Unfriendly atheist response: no one is rationally justified in believing that GOD exists. • Indifferent atheist response: the atheist takes no position on whether or not a theist’s belief in the existence of GOD is based on rational grounds. • Friendly atheist response: some theists are rationally justified in believing that the theistic GOD exists. Rowe thinks only the third position is justifiable. Why the Friendly Atheist is Right First, the friendly atheist (FA) is not taking a paradoxical or incoherent position, because in thinking someone can be rationally justified in holding that the theistic position on the existence of GOD, the FA is not committed to the view that a false belief can be rationally justified. This is because the truth of a belief is not a necessary condition for being rationally justified in having that belief. Rowe’s defense of the FA depends on: Thinking that person X can believe P, which they think they are rationally justified in believing, while also believing that person Y is equally rationally justified in believing the opposite of P. Rowe’s counterexample: me, my downed plane, and the rationally justifiable beliefs held by me, and my friends on shore, about my continued existence. Rowe’s defense of FA response to theistic belief in GOD depends on the claim that we can see how someone could, given other beliefs they hold, come to believe in the theistic account of GOD’s existence by rejecting the atheist’s inductive argument against the existence of GOD. Does this mean the FA is committed to a STANDOFF? No. The FA can understand why the theist believes their counterargument, and so rejects the atheist’s inductive argument, but this does not mean the FA is committed to the view that their own argument is unsound. Rather, they can continue to think that, if the theist saw why the premises of their argument are true, they would relinquish their otherwise reasonable grounds for rejecting it.