Kõne- ja muusikahelide suhetest

advertisement

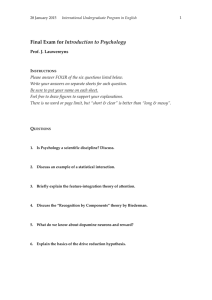

Music and speech as the two possibilities of self-expression with the human voice Jaan Ross Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre University of Tartu jaan.ross@ut.ee smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 1 Where is Estonia? In North-Eastern Europe, on the coast of the Baltic Sea, south of Finland, west of Russia, and north of Latvia. It belongs to the three Baltic countries, the other two of which are Latvia and Lithuania. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 2 Estonia has a territory of 45.2 km2 a population of about 1.4 million people a capital called Tallinn (about 0.4 million people) an official language – Estonian, which is close to Finnish a significant Russian-speaking minority a rich medieval architectural heritage from the Hanseatic times in the historical center of Tallinn smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 3 Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre has about 600 students has the academic staff of about 250 teachers was founded in 1919 has originally been designed much after the pattern of the conservatory in St. Petersburg hosts the Department of Musicology smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 4 Outline of the lecture Properties of sound Quantity in the Estonian language Interplay between meter, rhythm and language prosody in folksongs Veljo Tormis, folksongs and the new simplicity Pairwise variability index in speech and music smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 5 Properties of sound http://www.dsptutor.freeuk.com/analyser/SA102.html PHYSICS MUSIC AND SPEECH property unit property character unit frequency Hz pitch, fundamental frequency (F0) logarithmic, relative semitone sound pressure level (SPL) dB (logarithmic, relative) dynamics, loudness ranking scale absent: pp, p, mp, mf, f, ff duration (milli)second rhythm, quantity linear, relative quarter note, eighth note etc. the rest, i.e. spectral dynamics (cf. with the ASI definition) absent timbre, (phoneme) quality complex absent smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 6 Primary and secondary properties of sound Primary properties in speech: segmental, i.e. timbral or spectral Secondary properties in speech: tone (pitch), quantity (duration), intensity; called prosodic features or suprasegmentals Primary properties in music: pitch and rhythm (duration) Secondary properties in music: timbre and dynamics (intensity changes) smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 7 smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 8 smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 9 Some languages explore secondary properties as primary In Chinese languages, different tone contour patterns are used similarly to the segmental properties, i.e. for distinguishing lexical and/or grammatical meaning http://www.wku.edu/~shizhen.gao/Chinese101/pinyi n/tones.htm In Baltic-Finnic languages (e.g., Estonian or Finnish), different quantity patterns are used similarly to the segmental properties, i.e. for distinguishing lexical and/or grammatical meaning Tahad saada, saada sada If you want to get [it], you should send 100 [€, $, etc.] smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 10 In the overtone singing of South Siberia and Mongolia, spectral properties of sound are explored for creation of the musical structure the fundamental and the upper partials disintegrate, so that an audible polyphony emerges on the basis of a single sound source in order to achieve this, partials from 6 to 12 are made audible one by one, using a special configuration of the vocal tract usually a four-note scale is used in the upper voice (G-C-D-E-G) there is a sharp timbral contrast between the two voices smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 11 http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?articleID=000C5ABE-B1351CBC-B4A8809EC588EEDF the harmonic row consists of the fundamental (F0) with upper partials smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 12 Quantity in Estonian ternary opositions (short, long, overlong), which is unusual contrast of short and long is not the same as contrast of long and overlong productive trochaic pattern vas-tas-ti-kus-ta-ta-ma-tu-ma-te-le-gi sa-lon-ki-kel-poi-nen smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 13 Possibilities of V1 and C2 variation in twosyllable Estonian CVCV words sagi [saki] (to hustle 2 sg imper) - saagi [sa:ki] (harvest gen sg) - saagi [sa::ki] (saw part & ill sg) sagi [saki] - saki [sak:i] (notch gen sg) sakki [sak::i] (notch part & ill sg) sagi [saki] - [sa:k:i] Ø - saaki [sa::k::i] (harvest part & ill sg) smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 14 Observations in connection with V1 and C2 variation a phonetically complete paradigm is based on 4 semantically different words (sagima, saak, saag, sakk) distinction of g and k in spelling is not based on their different sound quality one possibility in the paradigm remains unused (V1 and C2 both long) V1C2 combinations long-overlong and overlong-long are excluded spelling of C2 is phonetically inconsistent, which justifies spelling errors (minu tupa, lähen köökki) smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 15 Baltic-Finnic old folksongs (runic songs, runo songs, Kalevala songs) a few thousand years old start to disappear since the end of 18th century main characteristics: alliteration and assonance, parallelism of verse lines, and trochaic 4-feet meter texts and tunes may be independent from each other smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 16 “There is no doubt that since the 2nd half of the 18th century, the old runic folksongs which were strongly disapproved by local pastors as well as leaders of the Moravian brothers, gradually started to be replaced by a new musical idiom among the Estonian-speaking serfdom. This has created the basis for future development of the polyphonic choral singing tradition. Learning Protestant hymns in schools and their congregational singing in churches hardly has had too much influence upon this change. Rather, it were the ‘harmonic’, i.e. multi-voiced, and emotional songs of the Moravian brothers, as it has been pointed out in 1791.” Karl Leichter, “Keset muusikat”, 1997 (orig 1956), p 464 smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 17 The Baltic-Finnic nations (ethnic groups): Finns, Estonians, Karelians, Vepsians, Votes, Izhorians, and Livs smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 18 August Wilhelm Hupel (1777), Topographische Nachrichten von Lief- und Ehstland (Topographical Communications from Livonia and Estonia) II, Appendix smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 19 smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 20 [Chr. Schlegel] (1830), Reisen in mehrere russische Gouvernements, 5. Bändchen. Meiningen: Keyssner smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 21 There is no correlation between word stress and syllable duration: short syllables may be stressed and long syllables unstressed. Metrical oppositions may be accomplished using both stress and duration. ha- ned hal- jas- ta hõ- be- dat position 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 meter + - + - + - + - word stress + - + - - + - - syllable duration - + + - - + smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 22 Distribution of syllables/notes in a Karelian lament. Left: all syllables/notes, right: short (CV) and long (CVV) syllables/notes separated. Jaan Ross ja Ilse Lehiste (1996), "Silpnootide pikkusest ühes karjala itkus," rmt Congressus Octavus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum 10.-15. 8. 1995, pars III (red H. Leskinen, S. Maticsák & T. Seilenthal), Jyväskylä: Moderatores, lk 45-48 smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 23 measured (ms) Syllable/tone durations in folksongs 600 400 200 0 0 100 200 300 400 500 predicted (ms) Syllable durations predicted according to: M. Mihkla, A. Eek and E. Meister (1999), “Text-to-speech synthesis of Estonian,” in Eurospeech ‘99: Proceedings of the European Speech Communication Association. Budapest, pp 2095-2098 smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 24 S1/S2 in speech (left, 2 dictors) and in singing (right, 3 singers). Vertical bars correspond to standard deviation. In speech, short, long and overlong words can be distinguished well on the basis of S1/S2. In singing, statistically significant differences between short, long and overlong words are mostly absent. Jaan Ross and Ilse Lehiste (1994), "Lost prosodic oppositions: A study of contrastive duration in Estonian funeral laments," Language and Speech 37, 407-424 smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 25 Average durations of sound events (ms) at ictus (rise) and off-ictus (fall) positions in a folksong melody Fall Normal Broken Rise 330 320 310 300 290 280 270 260 250 240 Broken lines are those where the word stress pattern does not coincide with the metrical accent pattern. The performer is LK from Haljala. The data are averages from four recorded songs, the total number of measured verse lines being 152 and that of sound events > 1200. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 26 smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 27 Veljo Tormis (s 1930) “I do not use folksongs. The folksongs use me.” Minimalism and the new simplicity in connection with Tormis’ works “The Lost Geese” from a set “Two Estonian runo songs” (1973-74). Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, conductor Tõnu Kaljuste smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 28 How are the sounds used in the Baltic-Finnic runic songs? modus vivendi between speech, music and meter text semantics dominates over the musical expressivity musical isochrony tends to level off linguistically relevant quantity oppositions Ictus positions are systematically longer than offictus positions, which provides support for the duration-based meter theory smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 29 The Pairwise Variability Index: Background in Linguistics The Pairwise Variability Index (PVI) is a metric used for quantifying speech rhythm. It was originally devised for the calculation of rhythmic differences between varieties of English (Low et al. 2000) It provides an alternative to the traditional view of rhythm isochrony (‘syllable timing’ vs. ‘stress timing’) The PVI captures the difference between adjacent linguistic units (syllables or feet) E.g. the more syllable timed the language is, the lower its PVI. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 30 Grabe, E., & Low, E. L. (2002). Durational variability in speech and the rhythm class hypothesis. In C. Gussenhoven & N. Warner (Eds.), Laboratory Phonology, 7, 515-546. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 31 Pairwise Variability Index subtract the value (e.g. duration) of previous unit from the present value multiply by 100 to get a whole number PVI n dk dk1 PVI 100 /(n 1) k2 (dk dk1 ) /2 sum absolute values of all successive pairwise differences divide by the number of pairs normalise by expressing difference as a fraction of the mean of the two units smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 32 Background in Music Theory Musical nPVI values, while potentially influenced by language rhythm, are sensitive to the genre and style. This is tested on the basis of Estonian vocal music because vocal music is more likely to reflect prosodic features of the language than instrumental music (Ross and Lehiste 2001), and should, at least in theory, show an nPVI more similar to speech rhythm. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 33 smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 34 Hypothesis Musical nPVI values, while potentially influenced by language rhythm, are sensitive to the genre and style. This is tested on the basis of Estonian vocal music because vocal music is more likely to reflect prosodic features of the language than instrumental music (Ross and Lehiste 2001), and should, at least in theory, show an nPVI more similar to speech rhythm. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 35 Composers (1) Mart Saar (1882-1963) composed his songs in the 1920s and 30s influenced by the impressionism and expressionism of the early 20th century. One of the founders of the Estonian national style. From: Soololaulud 3 [Solo songs 3]. Tallinn, 1984. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 36 Composers (2) Eduard Tubin (1905-1982) wrote his solo songs during the pre-war period representing the late romantic style of the 1930s and influenced by Estonian folk music. From: Soololaule [Solo songs]. Tallinn and Stockholm, 1988. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 37 Composers (3) Veljo Tormis (1930) created his folk-music-based song in the 1960s and 1970s. From: Neli eesti jutustavat rahvalaulu [Four Estonian narrative folksongs] and Kuus eesti jutustavat rahvalaulu [Six Estonian narrative folksongs]. Tallinn, 1972. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 38 Method A comparable number of solo songs was chosen for each composer: The total number of analysed melodic segments was 220: Saar (16), Tubin (15), Tormis (10). Saar (54), Tubin (83), Tormis (83). The calculation of nPVIs was carried out using the printed scores by counting the rhythm based on the vocal line. Adjacent note durations were compared to each other. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 39 Method nPVIs were calculated for each melodic segment (phrase) which was defined as a succession of notes not interrupted by any pause. Segments shorter than 12 notes were excluded from the analysis, and segments longer than 125 notes were cut into pieces, i.e. the 126th note in a succession of notes was considered to start a new segment. Consequently, the length of a melodic segment could vary between 12 and 125 notes. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 40 Results The average nPVI values for the solo songs by Saar and Tubin are significantly higher than those for Tormis: 47.0 and 42.1 vs. 22.2 (p<.0001). There is no significant difference between the nPVI values of Saar and Tubin’s songs. A comparison of the nPVI values for music with Estonian speech shows that the average syllable nPVI (5 speakers) of Estonian speech - 44.0 (Asu and Nolan 2006) - is very similar to and falls between the nPVI values of the songs by Saar and Tubin. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 41 Average nPVI values for the three Estonian composers and Estonian speech (Syllable nPVI) smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 42 Conclusions Although there is a striking correspondence between Estonian speech rhythm and that of the music of Saar and Tubin, the music of Tormis is rhythmically distinct. This supports our hypothesis that style- and genreconditioned characteristics of music can override linguistically conditioned characteristics. The prediction of the rhythm of music on the basis of speech rhythm may be an oversimplification. Similar nPVI values of Saar and Tubin’s solo songs reflect similar aesthetic principles of the two composers. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 43 Overall conclusion I have discussed how music and speech explore their common domain of sounds in a mostly separate but sometimes overlapping manner. Further, I have discussed the so-called hybrid form of different types of singing which combine both the music and the language, and demonstrate how occasional conflicts which occur between music and speech in singing as an example of modus vivendi, can reasonably been solved in the musical practice. smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 44 Thanks to my colleagues who have contributed to those studies Eva Liina Asu-Garcia (University of Tartu) Ilse Lehiste (Ohio State University) Meelis Mihkla, Institute of Estonian Language Allan Vurma (Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre) smART psychology, Dolný Kubín, 13-20 July 2008 45