Antigone intro

ANTIGONE

WHAT THE AUDIENCE KNEW

Greek Tragedy depended heavily for its effects on the audience already knowing the story that was to be presented. This put the audience in a position of superior power to the characters in the plays. The audience knew the future which the characters in the play did not. They could then witness how the characters, as presented by the author, would deal with the nightmares to come.

In this play, ANTIGONE, the audience already knew that:

1) Antigone would refuse to obey and that Creon would sentence her to death.

2) Creon himself would be cursed by the Gods, thus sharing in the tragedy of the Oedipus.

3) His son, Haemon, would choose love over loyalty to his father and he, too, would die.

4) The army of the Argives was not defeated. They were waiting outside the city for a chance to attack again despite the death of Ployneices. They did attack and Creon went down in the fighting. Thebes was sacked and its citizens enslaved.

5) In some of the stories, Creon died condemned as a tyrant and as one who failed his city. In others, he learned from the terrible lesson Antigone had taught and ruled for several years as a just king before dying in the final battle against the Argives.

Sophocles.

Born about 496BC and died 406BC

Sophocles is one of the three greatest of Greek Tragedians; the other two were Euripides and

Aeschylus.

The story of Antigone and the family she came from was told in many different ways. Sophocles wrote three plays concerning this family and wrote them in the following order”

1) Antigone produced about 442 B.C.,

2) Oedipus the King produced sometime soon after 430 B.C.,

3) Oedipus at Colonus produced after his death.

In terms of the actual stories about this family, the correct order should be 2,3 and 1.

THE STORY OF OEDIPUS

The following is the story of Oedipus as Sohocles wrote it. There are other versions. None of these is the exact or correct version. There are several versions, all equally true.

Laius, the King, and Jocasta, the Queen, of the Seven Gated City of Thebes are warned by the God

Apollo, when he speaks through the Oracle at the shrine of Delphi, that any son they may have will kill his father. Terrified by this prophecy, they give their son to a shepherd and order him to take the child out to the mountainside and leave it exposed to the wild animals and birds. The child’s feet are pierced with metal pins to cripple it and the shepherd takes it away

But he is not able to abandon the child; instead, he gives it to another shepherd who, in turn, carries the child across the mountain range, the Cithaeron, to the city of Corinth. The king,

Polybus, and the queen, Merope, are childless and the child is given to, and subsequently adopted by, them. The boy is named “Oedipus.” In the Greek of the play, the name Oedipus suggests

‘swollen foot.’ He grows to a young man, happy in his acceptance of Polybus and Merope as his parents until, at a banquet, a drunken guest states that he is not their natural son, something he cannot forget despite their attempts to reassure him otherwise. Desperate for some word he can fully believe, he journeys to the Oracle at Delphi where Apollo tells him that he will murder his father and marry his mother. a girl’s gotta do what a girl’s gotta do

Horrified, he vows never to return to Corinth and travels southeast then east through the mountain defiles of Mount Parnassus until he reaches a narrow place where three roads meet.

Here, he meets an old man journeying in a cart and attended by several retainers. A quarrel over the right of way ensues which leads quickly to a fight during which Oedipus kills the old man and all the men (so he thinks) attending him. This old man is his natural father, Laius. One of the retainers survives to return to the city of Thebes and relate the sad news of the murder of the

King.

Oedipus continued his journey arriving eventually at the plains that surrounded Thebes to learn that a monster, the Sphinx, with the body of a winged lion and the face of a female was tormenting the city. The Sphinx insisted that it would continue its depredations until the riddle it had many times asked was solved. Oedipus solved the riddle and the Sphinx threw itself to death off the rocks. The Thebans, after the death of their king, had promised to anyone who could solve the riddle, the throne of the city and the hand of the widowed queen, Jocasta.

Oedipus claimed his reward and lived for many years as a much loved king and ruler of the city fathering two sons, Eteocles and Polynices, and two daughters, Antigone and Ismene, on his wifemother. Thus he fulfilled, all unknowingly, the prophecy of the Oracle.

A plague suddenly struck and devastated the city. In despair, Oedipus has the Oracle consulted, the answer given being that the gods were angry and the plague would cease only when the murderer of Laius was found and either executed or exiled. Oedipus pronounces a curse on the unknown murderer and initiates investigations to find him. The process of the investigations reveals slowly, but completely, the truth, which no one had known. Jocasta, horrified at what has happened, hangs herself and in a moment of terrible grief and guilt, Oedipus takes the pins from the dress on her body and drives them into his own eyes.

He can no longer rule so he hands over power to Creon, Jocasta’s brother and his two sons, who, together, form a triumvirate to rule the city. But the sons’ behaviour, their constant quarreling over who had the right to be king, offends their father and, after pronouncing a curse on them, he leaves the city to wander as a beggar in the lands of Greece; Antigone accompanies him. The curse, that the brothers will each die at the other’s hand, is not lifted.

Etoecles wins the dispute over the kingship but Polynices refuses to accept the decision and leaves Thebes to go Argos and there raise an army to help him capture and rule the city.

He was successful in this but as he was about the task, the Oracle again pronounced saying that wherever the old man Oedipus died, then the city in whose territory that place lay, would be blessed by victory over its enemies. A race now began between Creon, acting on behalf of

Eteocles and Polynices, acting for himself, to find Oedipus and make sure that he died in their respective territories. Oedipus, assisted by Antigone, had arrived at a small village called Colonus near the great and sacred city of Athens. There he died.

Polynices led his soldiers against the city but was repulsed and Eteocles left the safety of Thebes with his army to finally defeat his hated brother. In the battle, the brothers gradually approached each other, finally engaging in single combat and each delivering the other a fatal stroke. Creon is now heir to a city dangerously divided in its sympathies. He deems an honourable burial for

Eteocles but none for Polynices and death for anyone who disobeys this order. Antigone, now returned to Thebes, cannot accept this judgement and resolves to go against it. It is at this situation that the play opens. a girl’s gotta do what a girl’s gotta do

The Birth of Classical Western Drama

Before the ancient Greeks ever staged their first play, they were already long in the habit of holding annual festivals to Dionysus, the god of fertility, and the god of wine. Even without too much concrete information about these festivals, we can imagine what a spectacle they must have been, with the entire town gathered for singing and dancing and storytelling, and other rites. The versified stories were about Dionysus and other Greek gods, as well as infamous, legendary culture-heroes. I can almost see those pots of wine as they were filled and refilled to overflowing, every citizen of the town doing his or her duty, showing up to pay homage to the god of fertility. The stories had their moment at center stage, when long narrative performances ("dithyrambs") entertained the festival goers with poetry spoken or chanted to musical accompaniment.

Somewhere around the sixth century B.C., an innovative poet named Thespis had the revolutionary idea that acting the story told in the dithyramb might be more interesting than simply telling it. He is generally credited as the world's first

"actor," which is why some in that profession are sometimes called thespians. Not much later, Aeschylus (who wrote The Orestia) added a second actor, and not long after that-in head to head competition with Aeschylus-Sophocles added a third.

Greek theater was born.

From its golden age, classical Greek theater has sent down through the foggy ruins of time incredibly resonant works of literature that are still abuzz with meaning, even today. Amazingly, almost twenty-five hundred years separate us from the works of playwrights like Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, yet their comedies and tragedies, firmly situated in ancient Greece, still fascinate us. The issues they grappled with, their insights into human behavior and motivation still resonate with us. Discovering our modern selves peeking out from these ancient texts is often a heady, exhilarating experience-it's what literature is all about.

Conventions of the Greek Theater

The Bedford Introduction to Literature (pp. 982-984) provides us with a quick overview of the way ancient Greek plays were staged.

Plays were performed in huge amphitheaters carved into hillsides. These outdoor arenas seated thousands-as many as 15,000 people. The seats faced an

"orchestra" or "dancing place" behind which actors played their scenes in front of a "skene"-the building behind the stage where actors exited and changed costumes. Gradually it became customary to paint the wall facing the audience to suggest a "set"-a particular setting or place where the scenes were taking place.

A few of the conventions of Greek theater are not familiar to us now, and they bear explaining. First, each play had its "chorus," or group of men, a dozen or so, who would observe the action from the orchestra, and between episodes would sing and dance their commentary on the action. Sometimes the chorus leader would even participate in the scenes by engaging the characters in dialogue, as he does towards the end of Oedipus the King. The chorus' role was

to model a response to the action unfolding on the stage. They represented public opinion, the public's response to the events of the play. They might

provide background information (exposition), or tell us what they think of

the relative virtue of the characters-good or ill. They might try to offer

advice, or admonish bad behavior. Whatever their precise function, their a girl’s gotta do what a girl’s gotta do

poetic commentary following each episode must have been a crucial part of the entertainment, as they would sing and dance and chant rhythmic lines of poetry between scenes. I can imagine they provided a sublime, beautiful musical interlude!

Another Greek convention was the "god in the machine" (deus ex machina in

Latin). This was a device some playwrights used to resolve conflicts when they were too difficult for the characters to resolve. Literally a "god" was lowered onto the stage by a mechanical platform (I imagine something like a window-washer's unit), descending from the roof of the skene, rescuing the characters from themselves. It's interesting to note that Sophocles-innovator that he indeed wasnever made use of this device. He must have thought it too simplistic, too contrived. That's the way we think of it today as well-a device that provides an

easy-out.

Structurally, Greek plays are somewhat different from modern drama, but still very recognizable. Things haven't changed as much as they might have in 2500 years! There's a "prologue" which provides the background to the main actioninformation we need to appreciate what's about to happen. Then there's a

"parados" in which the chorus arrives to "spin" the prologue-providing the audience with its perspective on what was just learned. Then there are several

"episodia"-episodes, or scenes-which contain the main action of the play, its dialogue, speeches, clashes. After each episode, a "stasimon" or choral ode follows to interpret what just happened. The last scene is known as the

"exodus"-it provides the resolution and the characters make their exit.

To be one of those lucky Athenians gathered at the temple theater to watch the original world premier of Oedipus the King on that warm, long gone spring day, pondering those famous last words….

"Now as we keep our watch and wait the final day, count no many happy till he dies, free of pain at last."

TRAGEDY

Suffering. Human suffering. Unfortunately it's all around us, every day, if we open our eyes to see it. "Count no man happy till he dies." No one is safe; we're all vulnerable. And we can't always shield ourselves from that basic but terrifying truth, as much as we may want to. There it is. A hero rushes to someone's rescue and is killed in the process. That's bad enough. But what about the hero who rushes to someone's rescue, insisting on doing it alone, unwilling to risk anyone else's life-or feeling overconfident, maybe-and dies because he tried to make the rescue alone? A child dies of a disease. That's bad enough. But then you learn she died of a curable disease, but her family didn't have the resources to get her the treatment.

Are those kinds of suffering the same thing as tragedy? Yes and no. Yes, we commonly refer to all of that as "tragedy." But no, the ancient Greeks-Aristotle in particular-meant something along the same lines but even more specific when they used that term.

The Greek tragedians were interested in how the human spirit responded

in the face of suffering. Does the hero acknowledge it, dance with it, overcome it, or become crushed by it? In your text, Michael Meyer tells us, "A literary tragedy presents courageous individuals who confront powerful forces within or outside themselves with a dignity that reveals the breadth and a girl’s gotta do what a girl’s gotta do

depth of the human spirit in the face of failure, defeat, and even death."

And what's at stake is usually more than an individual life-it's the life of the state, the fate of the community, that's in danger.

The best source for understanding the nature of Greek tragedy is still Aristotle.

Aristotle's "On Tragic Character" (pp. 1030)

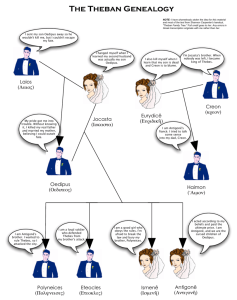

KEEPING IT IN THE FAMILY:

Oedipus the King & Antigone

In Thebes

Polydorous

Labdacus

Laius

Oedipus

Jocasta

Eteocles (s)

Polyneices (s)

Antigone (d)

Ismene (d)

Creon

In Corinth

Polybus Merope

Oedipus

a girl’s gotta do what a girl’s gotta do

a girl’s gotta do what a girl’s gotta do