p - Rutgers University

advertisement

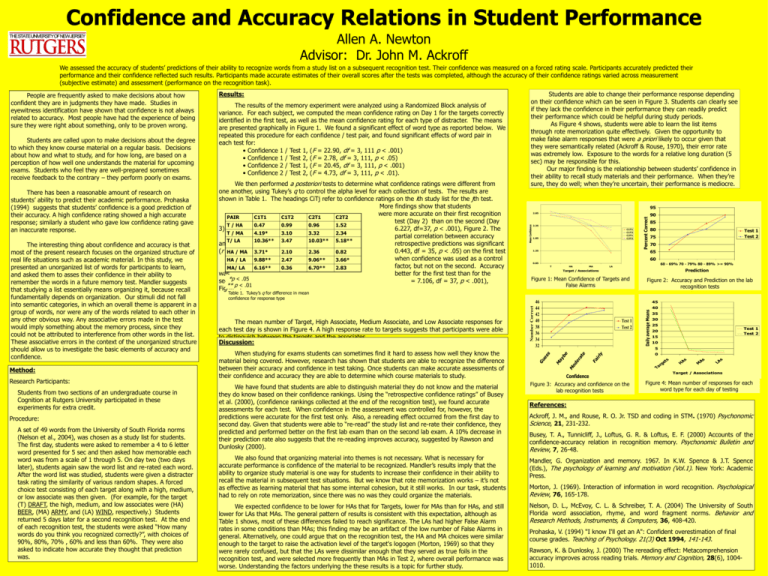

Confidence and Accuracy Relations in Student Performance Allen A. Newton Advisor: Dr. John M. Ackroff We assessed the accuracy of students’ predictions of their ability to recognize words from a study list on a subsequent recognition test. Their confidence was measured on a forced rating scale. Participants accurately predicted their performance and their confidence reflected such results. Participants made accurate estimates of their overall scores after the tests was completed, although the accuracy of their confidence ratings varied across measurement (subjective estimate) and assessment (performance on the recognition task). Research Participants: Students from two sections of an undergraduate course in Cognition at Rutgers University participated in these experiments for extra credit. Procedure: A set of 49 words from the University of South Florida norms (Nelson et al., 2004), was chosen as a study list for students. The first day, students were asked to remember a 4 to 6 letter word presented for 5 sec and then asked how memorable each word was from a scale of 1 through 5. On day two (two days later), students again saw the word list and re-rated each word. After the word list was studied, students were given a distracter task rating the similarity of various random shapes. A forced choice test consisting of each target along with a high, medium, or low associate was then given. (For example, for the target (T) DRAFT, the high, medium, and low associates were (HA) BEER, (MA) ARMY, and (LA) WIND, respectively.) Students returned 5 days later for a second recognition test. At the end of each recognition test, the students were asked “How many words do you think you recognized correctly?”, with choices of 90%, 80%, 70% , 60% and less than 60%. They were also asked to indicate how accurate they thought that prediction was. 2.35 1.85 1.35 We have found that students are able to distinguish material they do not know and the material they do know based on their confidence rankings. Using the “retrospective confidence ratings” of Busey et al. (2000), (confidence rankings collected at the end of the recognition test), we found accurate assessments for each test. When confidence in the assessment was controlled for, however, the predictions were accurate for the first test only. Also, a rereading effect occurred from the first day to second day. Given that students were able to “re-read” the study list and re-rate their confidence, they predicted and performed better on the first lab exam than on the second lab exam. A 10% decrease in their prediction rate also suggests that the re-reading improves accuracy, suggested by Rawson and Dunlosky (2000). 85 80 Test 1 Test 2 75 70 65 60 - 69% 70 - 79% 80 - 89% >= 90% 0.85 T HA MA LA Prediction Target / Associations Figure 1: Mean Confidence of Targets and False Alarms Figure 2: Accuracy and Prediction on the lab recognition tests Test 1 Test 2 Daily average Means 45 46 44 42 40 38 36 34 32 40 35 30 25 Test 1 Test 2 20 15 10 Confidence Figure 3: Accuracy and confidence on the lab recognition tests s LA A s M A s H rg et s 0 Ta Fa irl y 5 be When studying for exams students can sometimes find it hard to assess how well they know the material being covered. However, research has shown that students are able to recognize the difference between their accuracy and confidence in test taking. Once students can make accurate assessments of their confidence and accuracy they are able to determine which course materials to study. 90 60 Table 1. Tukey’s q for difference in mean confidence for response type The mean number of Target, High Associate, Medium Associate, and Low Associate responses for each test day is shown in Figure 4. A high response rate to targets suggests that participants were able to distinguish between the targets and the associates. Discussion: C1T1 C1T2 C2T1 C2T2 Percent Correct 2.85 M od er at e Method: 95 M ay The interesting thing about confidence and accuracy is that most of the present research focuses on the organized structure of real life situations such as academic material. In this study, we presented an unorganized list of words for participants to learn, and asked them to asses their confidence in their ability to remember the words in a future memory test. Mandler suggests that studying a list essentially means organizing it, because recall fundamentally depends on organization. Our stimuli did not fall into semantic categories, in which an overall theme is apparent in a group of words, nor were any of the words related to each other in any other obvious way. Any associative errors made in the test would imply something about the memory process, since they could not be attributed to interference from other words in the list. These associative errors in the context of the unorganized structure should allow us to investigate the basic elements of accuracy and confidence. We then performed a posteriori tests to determine what confidence ratings were different from one another, using Tukey’s q to control the alpha level for each collection of tests. The results are shown in Table 1. The headings CiTj refer to confidence ratings on the ith study list for the jth test. More findings show that students were more accurate on their first recognition PAIR C1T1 C1T2 C2T1 C2T2 test (Day 2) than on the second (Day T / HA 0.47 0.99 0.96 1.52 3) (t = 6.227, df=37, p < .001), Figure 2. The T / MA 4.19* 3.10 3.32 2.34 partial correlation between accuracy T/ LA 10.36** 3.47 10.03** 5.18** and retrospective predictions was significant (r = 0.443, df = 35, p < .05) on the first test HA / MA 3.71* 2.10 2.36 0.82 when confidence was used as a control HA / LA 9.88** 2.47 9.06** 3.66* factor, but not on the second. Accuracy MA/ LA 6.16** 0.36 6.70** 2.83 was better for the first test than for the *p <(.05 second t = 7.106, df = 37, p < .001), ** p < .01 Figure 3. Gu es s There has been a reasonable amount of research on students’ ability to predict their academic performance. Prohaska (1994) suggests that students’ confidence is a good prediction of their accuracy. A high confidence rating showed a high accurate response; similarly a student who gave low confidence rating gave an inaccurate response. The results of the memory experiment were analyzed using a Randomized Block analysis of variance. For each subject, we computed the mean confidence rating on Day 1 for the targets correctly identified in the first test, as well as the mean confidence rating for each type of distracter. The means are presented graphically in Figure 1. We found a significant effect of word type as reported below. We repeated this procedure for each confidence / test pair, and found significant effects of word pair in each test for: • Confidence 1 / Test 1, (F = 22.90, df = 3, 111 p < .001) • Confidence 1 / Test 2, (F = 2.78, df = 3, 111, p < .05) • Confidence 2 / Test 1, (F = 20.45, df = 3, 111, p < .001) • Confidence 2 / Test 2, (F = 4.73, df = 3, 111, p < .01). Students are able to change their performance response depending on their confidence which can be seen in Figure 3. Students can clearly see if they lack the confidence in their performance they can readily predict their performance which could be helpful during study periods. As Figure 4 shows, students were able to learn the list items through rote memorization quite effectively. Given the opportunity to make false alarm responses that were a priori likely to occur given that they were semantically related (Ackroff & Rouse, 1970), their error rate was extremely low. Exposure to the words for a relative long duration (5 sec) may be responsible for this. Our major finding is the relationship between students’ confidence in their ability to recall study materials and their performance. When they’re sure, they do well; when they’re uncertain, their performance is mediocre. Mean Confidence Students are called upon to make decisions about the degree to which they know course material on a regular basis. Decisions about how and what to study, and for how long, are based on a perception of how well one understands the material for upcoming exams. Students who feel they are well-prepared sometimes receive feedback to the contrary – they perform poorly on exams. Results: Number Correct People are frequently asked to make decisions about how confident they are in judgments they have made. Studies in eyewitness identification have shown that confidence is not always related to accuracy. Most people have had the experience of being sure they were right about something, only to be proven wrong. Target / Associations Figure 4: Mean number of responses for each word type for each day of testing References: Ackroff, J. M., and Rouse, R. O. Jr. TSD and coding in STM. (1970) Psychonomic Science, 21, 231-232. Busey, T. A., Tunnicliff, J., Loftus, G. R. & Loftus, E. F. (2000) Accounts of the confidence-accuracy relation in recognition memory. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 7, 26-48. We also found that organizing material into themes is not necessary. What is necessary for accurate performance is confidence of the material to be recognized. Mandler’s results imply that the ability to organize study material is one way for students to increase their confidence in their ability to recall the material in subsequent test situations. But we know that rote memorization works – it’s not as effective as learning material that has some internal cohesion, but it still works. In our task, students had to rely on rote memorization, since there was no was they could organize the materials. Mandler, G. Organization and memory. 1967. In K.W. Spence & J.T. Spence (Eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol.1). New York: Academic Press. We expected confidence to be lower for HAs that for Targets, lower for MAs than for HAs, and still lower for LAs that MAs. The general pattern of results is consistent with this expectation, although as Table 1 shows, most of these differences failed to reach significance. The LAs had higher False Alarm rates in some conditions than MAs; this finding may be an artifact of the low number of False Alarms in general. Alternatively, one could argue that on the recognition test, the HA and MA choices were similar enough to the target to raise the activation level of the target's logogen (Morton, 1969) so that they were rarely confused, but that the LAs were dissimilar enough that they served as true foils in the recognition test, and were selected more frequently than MAs in Test 2, where overall performance was worse. Understanding the factors underlying the these results is a topic for further study. Nelson, D. L., McEvoy, C. L. & Schreiber, T. A. (2004) The University of South Florida word association, rhyme, and word fragment norms. Behavior and Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 408-420. Morton, J. (1969). Interaction of information in word recognition. Psychological Review, 76, 165-178. Prohaska, V. (1994) "I know I'll get an A": Confident overestimation of final course grades. Teaching of Psychology. 21(3) Oct 1994, 141-143. Rawson, K. & Dunlosky, J. (2000) The rereading effect: Metacomprehension accuracy improves across reading trials. Memory and Cognition, 28(6), 10041010.