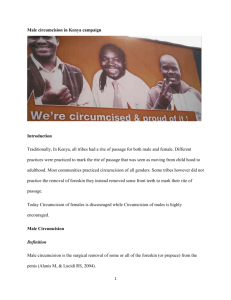

Review of MMC in KZN

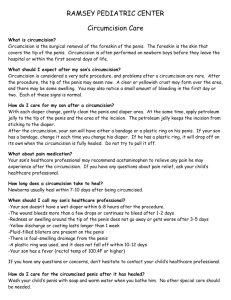

advertisement