I. Introduction

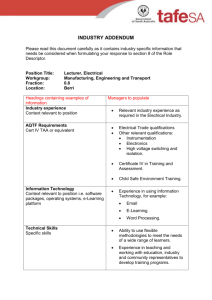

advertisement