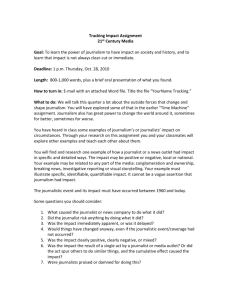

JN 510 week 6 The portrayal of women

advertisement

The portrayal of women journalists ‘We agreed that women were a nuisance in an office, anyway’ Early Pioneers • The entry of women into journalism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was similar to other white collar professions: a few determined, pioneering women found their way into newsrooms but they faced multiple obstacles: • A lack of educational opportunities • The prevailing view that the woman’s place was in the home • Fierce resistance from a largely male workforce But there were plenty of women hacks • Periodical and magazine journalism relied heavily on women contributors from the mid nineteenth century onwards • Two thirds of the contributors to the esteemed Chambers Edinburgh Journal were female. • Women also regularly worked under a male pseudonym. Even Mrs Pearl Craigie, the first President of the Society of Women Journalists, founded in 1894, wrote under the pseudonym of John Oliver Hobbes Numbers • According to Census figures for England and Wales, in 1861 around 145 females and 1,525 males described themselves as journalists • By 1901, the number of women journalists had risen to 1,249, around 9 per cent of the total • By 1931, that figure had risen further to 3,213, around 17 per cent. • The ratio of women to men then plateau-ed for three decades. Reasons for this include the introduction of a Marriage Bar at the BBC in 1932 and in newspaper organisations the assumption that once married a woman would leave journalism because the unsociable hours were contrary to the demands of a wife and mother • During this period the National Union of Journalists pursued discriminatory policies including suppressing female wages and imposing limits on the number of women accepted onto training schemes Later C20 (handout) • By 1964 a tiny number of newspaper front page bylines (3 per cent) were by women. This gradually increased to 1994 when nearly a third of front page newspaper bylines were by women. • Progress in newspapers has now stalled and reversed with only 13 per cent of front page stories by women in 2009 Fictional portrayals • The difficulty of asserting oneself in an overwhelmingly male preserve, and, once inside fighting the almost impossible struggle against being pigeon-holed into the features departments is a constant feature of fiction portraying woman journalists from Ella Hepworth Dixon’s The Story of a Modern Woman (1894), to, Monica Dickens’s bitter account of life on a provincial newspaper, My Turn to Make the Tea (1951). Other portrayals tend to depict female reporters either as drunkards (Stamboul Train), little more than whores who will do anything to get to the top of Fleet Street (Julie Burchill’s Ambition or A N Wilson’s My Name is Legion) or as irresponsible liars (Rita Skeeter). The Story of a Modern Woman (1894) • In The Story of a Modern Woman, protagonist Mary Erle, sitting nervously waiting for an interview outside the office of the editor of The Fan realises she is an outsider in the clubby male world of newspapers at the end of the nineteenth century: • ‘Ten minutes, fifteen minutes, twenty minutes went slowly by. The murmur of voices, the baritone laughter in the next room continued to be audible. At last, when Mary had finally made up her mind to go, the door was flung open and a young man with a high colour stumbled out. ‘Ta ta old chap, thanks awfully. See you in the club tonight,’ and, bestowing on Mary a prolonged stare, he disappeared down the long glass corridor’ (p45). My Turn to Make the Tea • In My Turn to Make the Tea, Poppy (who, as the only female reporter is the only person who ever makes the tea in the Downingham Post office) interferes with the printing of the paper in order to remove a story that, if published, would ruin a friend’s career. Poppy resigns, meeting the editor Mr Pellet halfway up the stairs as he is coming down to give her the sack: • It made quite a friendly transaction, and we agreed that women were a nuisance in an office, anyway… ‘We’ll miss you,’ he said, and they got a promising young lad of sixteen, fresh from school, to take my place on the Downingham Post (Dickens, 1962, p222). Edwardian Women • • Katherine Halstead in Philip Gibb’s Street of Adventure in1909: ‘We women wear out sooner. Five years in Fleet Street withers any girl. Then she gets crow’s feet round her eyes and becomes snappy and fretful or a fierce creature struggling in an unequal combat with men’. (Gibbs, 1909: 35-36). • Beautiful, brave, principled, yet sketchy - merely the object of the young hero Luttrell’s amorous awakenings. Her characterisation is limited to that of an unattainable spirited female ideal, who eventually spurns the hero for the sake of her work: ‘I must go back. I shall never settle down to the humdrum after all the rush and scurry of things. It is in my blood now. I must be seeing things and doing things. I want the old adventures, all the friends, and the good fun and the hard work, and the long hours and the indignities and the joys of journalism.’ (The Street of Adventure, p317) A salary of £4 a week on a ‘Conservative daily paper’ is preferable to Katherine than marriage to Luttrell. As a woman, she cannot do both (p.317). • • Katherine Halstead contd • She turned round in her swing chair and said: ‘If you will give me a cigarette I will tell you the lurid details.’ • ‘Take ‘em all’ said Brandon handing her his case. • ‘There’s been a suffrage raid this afternoon. Thirty-seven arrests. Crowd very rough. Chris Codrington and I were in the thick of it. The police got several women by the throats – and used quite unnecessary violence. Of course I shall not be allowed to say so.’ (p.43) More KH • ‘She seemed to have a touch of coquetry, yet she had spoken to him with an almost boyish candour, which he had found slightly disconcerting. She had a sharp tongue, yet she was not shrewish, and there was a pretty feminine light in her eyes. She had the gift of laughter – he had first heard her laugh on the night of his interview with Bellamy – yet once or twice there had been a certain wistfulness.’ (p.45) ‘Mother’ Hubbard • Mother figure • Sexless, although only in her late 30s • Heroically refuses to ‘puff’ a beauty doctor and gets the sack for it • ‘There was one place in London where Frank Luttrell spent many of his evenings when he was not doing late duty for the Rag. It was the flat on the third floor of the bookseller’s shop in Shaftesbury Avenue where the names of Margaret Hubbard and Katherine Halstead were written on the brass plate. ‘Mother Hubbard’ had given him a general invitation. ‘If you ever want to toast your toes before somebody eles’s fire,’ she said, ‘remember that we always burn the best coal.’ (p.110) Advises the young men on the paper • ‘Your heart is too big for your body young man,’ said Mother Hubbard severely. ‘What you want is a little less heart and a little more head. You have no business to throw your money away like this.’ (p.111) Plight of the working woman in 1909 • ‘The laws of social economy and their very nature force some women to go out and work, and the world is all the better for it. But somehow or other women have to pay a heavy price for liberty…some of them. They lose caste. Oh yes I have felt that many times. Also they lose their femininity – horrid detestable word…’ Other Edwardian fictional woman reporters • Adeline Sargeant’s The Work of Oliver Byrd (1902): • Heroine Eleanor Denbigh writes investigative campaigning articles about ‘the condition of children in certain London slums; and she had gathered together a mass of facts and details relative to their condition and their heredity which was becoming very useful to the statisticians and philanthropists of her time’ Dolf Wyllarde’s The Pathway of the Pioneer (1906) • Magda Burke edits a weekly illustrated paper and reports on sporting events such as the Ladies Swimming Competition at Westminster Baths (Wyllarde, 1914: 69) and a cricket match at Lord’s (although being a woman she was not given a seat in the reporters’ enclosure). Background • At the turn of the Twentieth Century, only a handful of women worked as journalists. The Daily Mirror, launched in 1903 started out with an entirely female workforce – although it was a short-lived experiment. When editor Mary Howarth was fired as editor, she returned to the features department of the Daily Mail, where she edited the women’s page. • Hamilton Fyfe who took over editorship described sacking the women as ‘like drowning kittens’ More Daily Mirror • The incompetence of the women journalists and their unsuitedness for the ‘rough old trade’ became the stuff of Fleet Street folklore: • ‘Alfred (Harmsworth) is supposed to have sent in champagne to revive those who fainted under stress. Some innocent girl, sub-editing an article from Paris, is credited with the headline ‘Our French Letter’, hurriedly changed by a man on the staff to ‘Yesterday in Paris’…Perhaps an exaggerated Victorian respect for womanhood misled Alfred, both about women readers and women journalists.’ (Ferris, 1971 pp 120-121) Steady Progress • In 1917, Alice Chalmers-Lawford became the NUJ’s first woman delegate to the Annual Delegate Meeting and in the immediate post war period the launch of several women’s magazine such as Good Housekeeping (1922), Modern Woman (1925) and Woman’s Journal (1927) required a larger body of female journalists to contribute to them • Of course the subject matter was mainly stereotypical fashion, cooking and childrearing Low estimation of women newspaper readers • “They [male editors at the Daily Mail] expected women to be interested solely in knitting jumpers, in caring for their complexions, in looking after babies, in cooking, in a ‘good’ murder and in silly stories about weddings…I wished to be treated as a person doing a job, instead of which some people were kind to the poor woman, some people were jealous of the damned woman and some people thought the tiresome woman had better go home and make way for a man.” From Mrs Charles Peel’s memories of being Daily Mail women’s page editor and contributor 1916 – 1920 Can you stand the strain little flower? • By the early 1920s enough young women were enrolling in the London University’s Journalism course for the lecturers to see fit to invite Evelyn Isitt, ‘of the London staff of the Manchester Guardian’ to give a talk on ‘The work of a woman general reporter’ to the students. Her advice is not altogether helpful: ‘before thinking of taking it up you should consider whether you can stand the strain, the long hours, the rush to get your copy ready in time…’ Misogynist tendencies then • Some critics associated the arrival of women with the disintegration of values in the press. This, for example from an essay in the Spectator by essayist and playwright St John Ervine: ‘….the most casual observer of the ‘national’ newspaper cannot fail to notice how womanised the popular press has become…Articles by, and about women prevail in these papers and editors, without any embarrassment will print ‘powerful articles’ by young ladies not long enlarged from school on the reform of Marriage or the reorganization of sex or the overhaul of religion. There seem to be many young ladies who will rearrange the entire Universe in eight hundred words for a fee of twenty guineas!’ (1930) …and now Pigeon-holing: Keeping Up Appearances • ‘…Daisy knew that instead of writing poetry, she ought to be writing her weekly articles on Women. Dreamily she mused on it while the bees hummed round her in the thyme. Should Clever Women Marry Stupid Men? Should Women and Men Marry At All? What is the Religion of Women? The Post-War Girl: is she selfish, rude, clever, stupid, drunk, thin, tall, dark, fair…Daisy sometimes wondered which of the figures of which she wrote she most detested. She desired very greatly to tell them exactly what she thought of them all, but this would not be accepted or paid for, and she had to go on babbling of them in half-witted phrases…’(p20-21) Frustration at her being pigeon holed • ‘Why was she thus doomed, she impatiently sighed, merely through an accident of sex, to write of these grotesque waxworks, of which intelligent persons have never heard? Why would they not let her write about inhuman things, about books, about religions, about places, about the world at large, about things of which intelligent persons had heard? ‘A subject for you, Miss Simpson: Can Women Have Genius? You might make something good of that, I think…’ (p22) Rose Macaulay suffered same • ‘…. Some time ago for instance the literary editor of a newspaper wrote to me asking if I would write an article for his paper on ‘Why I Would not Marry a Curate.’ I rang him up and gave him a suitable reply. He said, well then, would I write about a caveman…Shortly afterwards another editor inquired if I would write on ‘Should Clever Women Marry?’ (‘What the Public Wants’ A Casual Commentary, Methuen and Co 1925 General Criticism of working females at a time of unemployment • Winifred Holtby: ‘[working girls’] fiercest critics are often the wives of men who live in hourly fear of unemployment; mothers of beloved children whom they dream of in nightmares as suffering under the hardships of the Means Test and 2s a week allowance… • Strong ‘back to home’ pressure after WW1 • Magazines like Good Housekeeping energetically promoted the ‘return to home’ theme, recommending women, who may have worked during the First World War, now retreat back behind their front doors and make their homes cocoons of domesticity for their men folk. Daisy’s reaction • For Daisy, this complicated attitude results in a fractured personality that she simply cannot hold together: to her mother and features editors she is Daisy Simpson required to write inane articles on the modern woman; to the upper middle class circle to which she aspires to be part of, and to which her fiancé biologist Raymond Folyot belongs, she is bold, beloved Daphne, five years younger than Daisy. To yet another sphere she is Marjorie Wynn, author of popular novels and when her latest is a soar away success, a newspaper commentator required to write even more inane articles than Daisy Deviants • Social scientists characterise the women who entered journalism during the early years of mass newspaper production with reference to social science theories of ‘deviance’ similar to that used to describe female politicians. By choosing journalism, they were diverging both from the accepted role of the middle class woman as home maker, and were also diverging from acceptable female professions of nursing and teaching. Fictional Deviants • Katherine Halstead (Street of Adventure) is an unnatural woman in that she chooses journalism over marriage and babies (‘I pray God there may be babies,’ said Frank • ‘No,’ said Katherine, ‘not on £120 a year. I am not cut out for it.’ (Gibbs, 1909, p314) • Tommy in Tommy and Co doesn’t even know if she is a boy or a girl • Daisy Simpson (Keeping Up Appearances) is a social deviant, daring to set foot in the upper middle class Folyot household • Mabel Warren (Stamboul Train)is a sexual deviant (tweedwearing lesbian) More deviants • Helen Pratt(Christopher Isherwood’s Mr Norris Changes Trains, 1935) talks and behaves like a man: • At that time Helen was Berlin correspondent for one of the political weeklies and supplemented her income by making translations and giving English lessons…She was a pretty, fair-haired fragile-looking girl, hard as nails, who had been educated at the University of London and took Sex seriously..She could drink most of the English journalists under the table, and sometimes did so but more as a matter of principle than because she enjoyed it.’ (Isherwood, 1977, p.38) Modern deviants • Susan Street (Ambition) is an unnatural mother, giving up her son to pursue her career in tabloid journalism • Mary Much and Martina Fax (My name is Legion) are lesbians (again…) • Rita Skeeter: Rowling’s description of Rita mentions her ‘square jaw’ and ‘mannish hands’ – is this a veiled insult to the journalist she is based on, or is this yet another female deviant [is she really a man?] See Rowling’s Leveson testimony Graham Greene’s Stamboul Train (1932) • What does this chapter tell you about the image of Mabel Warren Greene wants to portray? Mabel Warren in Graham Greene’s Stamboul Train (1932) • Despite her masculine appearance and cynical toughness, also trapped by her gender. At our very first meeting with her, at Cologne Station, she muses on her role at her paper, the Clarion: ‘‘When you want sob-stuff, send Dizzy Mabel.’…there wasn’t a town of any size between Cologne and Mainz where she hadn’t sought out human interest, forcing dramatic phrases onto the lips of sullen men, pathos into the mouths of women too overcome with grief to speak at all…’(p.35). • We later learn in the novel that when it comes to being a journalist, she is anything but ‘Dizzy’ – she is focussed, fearless, tenacious and writes exemplary copy. Yet ‘Dizzy’ is the term all her colleagues – when they are mentioned they are all men’s names – have given her. Although a very different character to Daisy Simpson, Mabel too yearns to get out of the human interest stories and celebrity interviews she is paid to write and instead get her teeth into a proper news story. She also evidently presents herself in the Clarion as a man, as is clear in the copy she files to her newspaper office: ‘Our correspondent pointed out… ‘You have a wonderful knowledge of the female heart, Mr Savory,’ he said (p.96) Another example of the fractured personality. Yet Greene is not sympathetic • During the novel, she is permanently drunk, from our very first meeting: ‘But of course dear, I don’t mind your being drunk..’ (p.34) to our last, ‘there was a faint smell of liquor in the air,’ (p.194). In the intervening pages, she also gives off odours, mostly of alcohol, but also of ‘cheap powder’ (p.45); she is associated with the ‘gross bouquets’ of a field of cabbages that fills the compartment with a ‘smell of gas’(p.68) as she subjects Czinner to a gruelling interview. The image is reminiscent of Auden’s ‘Beethameer’ poem in The Orators, with the newspaper ‘nagging at our nostrils with its nasty news’ and reinforces the image of reporters as invasive and uninvited. Mabel herself, never waits to be asked into compartments, but doggedly pursues her prey ‘she ran him to earth in a second-class sleeper…she sat down without waiting for an invitation.’ • Yet Mabel is far more complex than the brutally dogged (Greene refers to her as ‘sadistic’ in A Sort of Life, (p.155)) reporter she first seems. She is permanently afraid that her pretty lover, Janet Pardoe, will leave her for a rich man and is painfully aware of her unattractive appearance: ‘In a mirror on the opposite wall Miss Warren saw her own image, red, tousled, very shoddy…’ (p.35) Greene’s journalists • Mabel, Minty (England Made Me, 1934), Fred Hale (Brighton Rock, 1938, Thomas Fowler, The Quiet American, 1955) • character of the journalist in Greene’s fiction as similar to that of his spies and assassins: information collection, often by shady means, double crossings, deception and the powerful and subjective process of producing information for an audience, whether newspaper readers or Secret Service handlers are activities shared by his journalists and his spies: ‘Journalism is a curiously grey profession, and this would again have appealed to Greene, who never tired of articulating his fondness for indeterminate areas in all human affairs.’ Chakrabarti, 2004, p.3 Influence of The Times • ‘I was happy on The Times, and I could have remained happy there for a lifetime…No one on The Times was ever known to be sacked or to resign. I remember with pleasure – it was a symbol of the peaceful life – the slow burning fire in the sub-editors’ room, the gentle thud of coals as they dropped one by one in the old black grate.’ • In A Sort of Life, he recalls some of The Times reporters he met during his three-year stint, and of particular note is Vladimir Poliakoff, the diplomatic correspondent, ‘In a grey homburg hat with a very large brim, who would come into our room to consult the files, carrying with him an air of worldliness and mystery (why was he not reading them next door in the foreign room where he naturally belonged? Perhaps he wished to remain for obscure reasons of state incognito)’. This romantic description illustrates the easy elision Greene makes between the spy/journalist character Journalist/Spy theme • Mabel the journalist is also Mabel the spy. Suspecting the elderly man with the moustache to be Dr Czinner, a Yugoslavian Socialist agitator who famously disappeared, suspected murdered by Government forces after giving evidence in a political show-trial she leaps onto the Orient Express, and follows him, doggedly, snapping at his heels as the train speeds across Eastern Europe. In a particularly tense scene, she steals into his compartment while he is out, reckoning she has three minutes to find some kind of clue among his belongings: • ‘First there was the mackintosh. There was nothing in the pockets…She picked up the had and felt along the band and inside the lining; she had sometimes found quite valuable information concealed in hats…’(p.57) Helen Pratt, Mr Norris Changes Trains (Christopher Isherwood, 1935) • • • • • heavy drinker Possibly also a lesbian Talks in very stilted tones like Mabel More masculine than the male yet effeminate narrator works in Europe rather than England, and is another tough customer but who, unlike Mabel, shows no signs of weakness. In fact here she is the opposite of Mabel –fragile and feminine on the outside, hard on the inside, as opposed to Mabel’s outer bravado and her inner self-loathing and vulnerablity: • At that time Helen was Berlin correspondent for one of the political weeklies and supplemented her income by making translations and giving English lessons…She was a pretty, fair-haired fragile-looking girl, hard as nails, who had been educated at the University of London and took Sex seriously..She could drink most of the English journalists under the table, and sometimes did so but more as a matter of principle than because she enjoyed it.’ (p.38) • astute political observer, correctly predicting the outcome of the presidential election in March 1932, when Hindenburg was reelected: ‘So the old boy’s done the trick again,’ said Helen Pratt. ‘I knew he would. Won ten marks off them at the office, the poor fools.’ (p.92) Redeeming features • loyal friend to Bradshaw, despite her disparaging remarks about his and his friends’ homosexuality: ‘I must say Bill you are a nice little chap but you do have some queer friends…you did know Pregnitz was a fairy,’ (p187). She is also a fearless reporter, coming into her own after the Nazis come to power in 1933, although her methods of obtaining information are occasionally cruel: • ‘But not even Goring could silence Helen Pratt. She had decided to investigate the atrocities [the Nazis’ ill-treatment of Jews and Communists] on her own account. Morning, noon and night, she nosed around the city, ferreting out the victims or their relations, cross-examining them for details. These unfortunate people were reticent of course, and deadly scared. They didn’t want a second dose. But Helen was as relentless as their torturers. She bribed, cajoled, pestered. Sometimes losing her patience, she threatened. What would happen to them afterwards frankly didn’t interest her. She was out to get facts.’(p.180) Isherwood’s own attitude to journalists • This mixture of approval and doubt about Helen’s tactics are a good reflection to Isherwood’s attitudes towards journalists at the time. He clearly enjoyed their company and spent time with the foreign press corps as he describes in his autobiography Christopher and His Kind: • ‘Some foreign journalists – those who were openly critical of the Nazi government – used to dine together, most evenings, at a small Italian restaurant. Among them was Norman Ebbutt of the London Times. Everybody else in the restaurant, including at least one police spay, watched them and tried to overhear what they were saying…Christopher [Isherwood – he refers to himself in the third person throughout] had got to know Ebbutt, so he went to him with the information [about the conditions of political prisoners held by the Nazis at the Nollendorfstrasse Barracks]. Ebbutt had already made himself unpopular with the authorities by his revelations; even his own editor was worried about his frankness.’ Isherwood’s Guilt? • By 1933, British newspapers had begun reporting the threat to the Jews posed by Hitler, with the Daily Express and Daily Mirror being the most outspoken. As a writer, Isherwood seems to have felt it was his duty to report as many details as he could about life in Berlin during this turbulent time, and, reading his autobiography, particularly when referring to journalists, it appears he feels he has in some ways fallen short of his task: • ‘Goebbels, the party propagandist, was obliged to make himself available to the foreign press. And it wasn’t too difficult to arrange interviews with Goering or even Hitler. Christopher wasn’t Jewish, he belonged to the Nazis’ favoured foreign race, he spoke German fluently, he was a writer and could easily have been accepted as a freelance journalist whom they might hope to convert to their philosophy…What inhibited him? His principles? His inertia? Neither is an excuse. He missed what would surely have been one of the most memorable experiences of his Berlin life.’ • Compare this rather shamefaced admission to Helen Pratt’s triumphant expulsion from Germany following a series of ‘scalding articles’: • ‘To hear her talk, you might have thought she had spent the last two months hiding in Dr Goebbels’ writing desk or under Hitler’s bed. She had the details of every private conversation and the lowdown on every scandal.’ (p.185) Examples too numerous to mention • Here, for example is a passage from Peter Foster’s The Spike (1965) a typical, and rather badly written ‘Fleet Street’ novel. The Editor (we never learn his name) wants to take a mistress: • ‘There were, as anywhere, amenable secretaries. Or he could have looked among the ranks of lonely, ambitious women journalists, a few of whom were quite attractive. Usually their own marriages had gone wrong on the grounds of organisational incompatibility, it being extremely difficult to run a home and satisfy a husband working conventional hours, and at the same time succeed in journalism. Wives found it difficult to convey the peculiar satisfaction of being printed in the paper, while few husbands could feel especially proud of what their wives wrote, and even less if it meant yet another late homecoming. So food and affections grew cold.’ • In this context the word ambitious is clearly used as criticism Julie Burchill’s Ambition (1989) • The novel opens with Susan Street, deputy editor of the Sunday Best, lying in bed next to the body of Charles Anstey, the editor, who has just died in the middle of them having sex. • Flashbacks chart the life of Susan from schoolgirl wannabe to deputy and then editor of a tabloid ‘whose circulation was three million and rising’ • In between shows the life of an ambitious journalist and the seedier side of tabloid journalism • Loses custody of her son but it doesn’t seem to bother her Ambition is partly autobiographical • ‘Julie – bookish, bright, midly delinquent – ran away to London aged 17 to answer an NME advertisement for a ‘hip young gunslinger’ and almost immediately became star of the rock press, writing about punk. Married her fellow gunslinger Tony Parsons, aged 18, had a son, Bobby, abandoned both in 1984 to run off with Cosmo Landesman, another journalist…(Interview with Lyn Barber, The Observer, 1998). Barber describes Ambition as ‘forgettable’ and it is fairly dire prose, but does capture the spirit of late 80s tabloid journalism pretty well. Wendy Henry and Patsy Chapman • Wendy Henry and Patsy Chapman were two tabloid Fleet Street editors in the 1980s: Wendy Henry edited the News of the World until 1988, when she moved to the Sunday People, Chapman took over from Henry on the News of the World. They were notoriously hard-nosed ruthless tabloid editors who had come up through the features pages and therefore were neither trusted nor respected by the male newsroom culture. Burchill has said that Susan Street is also partially based on the Fleet Street pair. ‘Killer Bimbos of Fleet Street’ • ‘Wendy Henry was the first ‘Killer Bimbo of Fleet Street’. She arrived, stilettos at the ready, to edit News of the World. She was the first female national newspaper editor that anyone could remember and certainly the flashiest. Short skirts and fishnets had not been standard editing gear before. Not everyone adjusted well. "I will not work for anyone wearing an ankle chain," cried Nina Myskow, who walked out as Ms Henry walked in, brandishing a brand of "yuck journalism" that would do for her in the end.’ Ann Treneman, Independent, 1998 Where are they now? • Where are the female editors of Fleet Street? The last to go was Rebekah Brooks who was famously compared to a witch (by a female lawyer) after her appearance at the Leveson hearing. • Er and again as she went to her trial this month Rita Skeeter • Rita: "How about giving me an interview about the Hagrid you know, Harry? The man behind the muscles? Your unlikely friendship and the reasons behind it. Would you call him a father substitute?" • Hermione Granger: "You horrible woman. You don't care, do you, anything for a story, and anyone will do, won't they?” (Goblet of Fire) Rita’s interview with Harry • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fJl96LYFG C8 Rowling on Rita • This is what Rowling has said of Rita: ‘Well I'll tell you the truth but I doubt very much that anyone's going to want to hear this. I tried to put Rita in Philosopher's Stone - you know when Harry walks into the Leaky Cauldron for the first time and everyone says, "Mr Potter you're back!", I wanted to put a journalist in there. She wasn't called Rita then but she was a woman. And then I thought, as I looked at the plot overall, I thought, that's not really where she fits best, she fits best in Four when Harry's supposed to come to terms with his fame. So I pulled Rita from Book One and planned her entrance for Book Four and I was really looking forward to Rita coming in Book Four. For the first time ever, my pen metaphorically hesitated over writing her, because I thought, everyone will think this is my response to what's happened to me. But the fact is, Rita was planned all along. Did I enjoy her a little more because of what's happened to me - yeah I probably did!’ Rowling at Leveson • How does her testimony reflect on her portrayal of Skeeter? A N Wilson’s My Name is Legion • Mary Much and Martina Fax (handout) • What does this excerpt tell you about Martina and Mary (and, also, the author’s view of women) Mattie Storin, House of Cards http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XH7kLSz0Eq4 • The TV series, based on the novel of the same name by Michael Dobbs was a hugely influential series in 1990s • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sDIdrbHuoWU • This year (feb 2013) returned to our screens, remade for American TV starring Kevin Spacey – a major Netflix coup • Shows that sex, power and journalism are a heady mixture US representations of women • Blood Diamond: Maddy Bowen: ‘let me do my work’ • http://www.imdb.com/video/screenplay/vi34 7799833/ • How is Maddy portrayed compared to the English journalists? How does she react with the Leonardo di Caprio character, how is she dressed, how does she talk? • His Girl Friday (will look at in American week)