docx - Evangelical Tracts

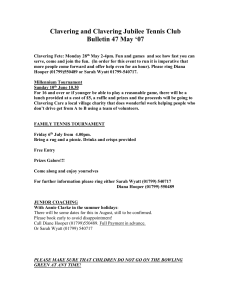

advertisement