Hematuria (Diagnostic approach)

advertisement

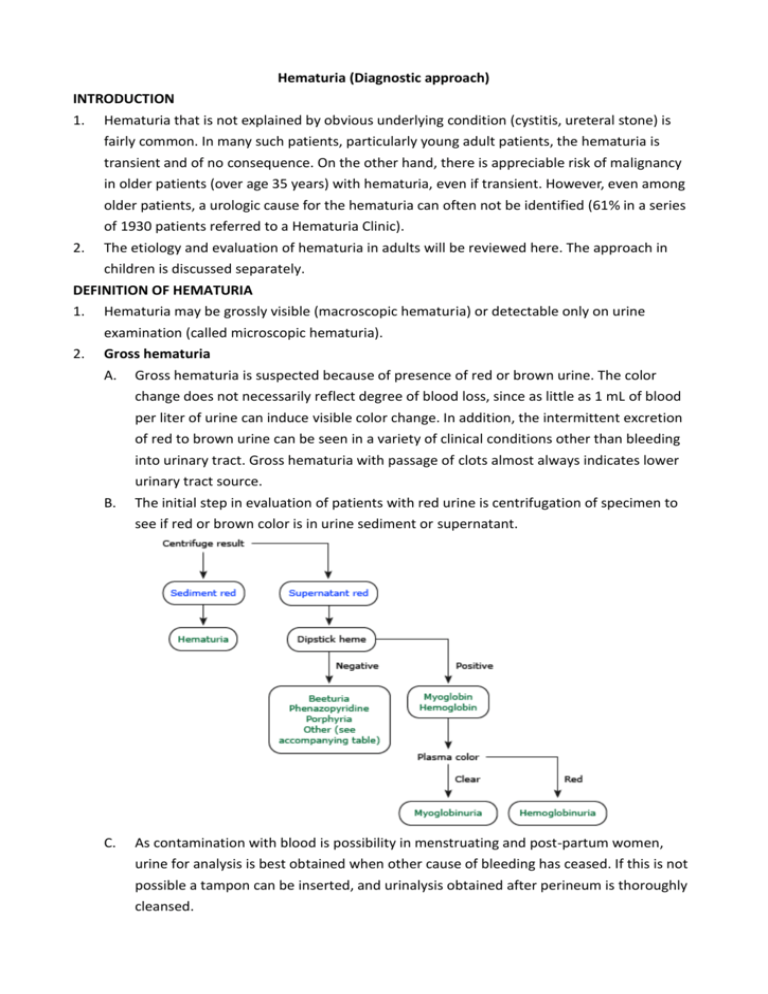

Hematuria (Diagnostic approach) INTRODUCTION 1. Hematuria that is not explained by obvious underlying condition (cystitis, ureteral stone) is fairly common. In many such patients, particularly young adult patients, the hematuria is transient and of no consequence. On the other hand, there is appreciable risk of malignancy in older patients (over age 35 years) with hematuria, even if transient. However, even among older patients, a urologic cause for the hematuria can often not be identified (61% in a series of 1930 patients referred to a Hematuria Clinic). 2. The etiology and evaluation of hematuria in adults will be reviewed here. The approach in children is discussed separately. DEFINITION OF HEMATURIA 1. 2. Hematuria may be grossly visible (macroscopic hematuria) or detectable only on urine examination (called microscopic hematuria). Gross hematuria A. Gross hematuria is suspected because of presence of red or brown urine. The color change does not necessarily reflect degree of blood loss, since as little as 1 mL of blood per liter of urine can induce visible color change. In addition, the intermittent excretion of red to brown urine can be seen in a variety of clinical conditions other than bleeding into urinary tract. Gross hematuria with passage of clots almost always indicates lower urinary tract source. B. The initial step in evaluation of patients with red urine is centrifugation of specimen to see if red or brown color is in urine sediment or supernatant. C. As contamination with blood is possibility in menstruating and post-partum women, urine for analysis is best obtained when other cause of bleeding has ceased. If this is not possible a tampon can be inserted, and urinalysis obtained after perineum is thoroughly cleansed. i. Hematuria is responsible if red to brown color is seen only in the urine sediment, with supernatant being clear. A rare exception is that lysis of RBC in patients with gross hematuria and very dilute urine can result in a red supernatant. D. If, on the other hand, it is the supernatant that is red to brown, then supernatant should be tested for heme (hemoglobin or myoglobin) with urine dipstick. i. A red to brown supernatant that is negative for heme (hemoglobin or myoglobin) is a rare finding that can be seen in several conditions, including porphyria (table 1), use of bladder analgesic phenazopyridine, and ingestion of beets in susceptible subjects. ii. A red to brown supernatant that is positive for heme is due to myoglobinuria or hemoglobinuria. How these disorders can be distinguished is discussed elsewhere. E. 3. Acute renal failure i. Gross hematuria occurring in patients with underlying glomerular disease has been associated with development of transient AKI. Renal biopsy shows distension of many renal tubules by intratubular red cells and tubular cell injury consistent with ATN. This association has been best described in patients with IgAN, but has also been noted in case reports of patients with TBMD and lupus nephritis, who were over-anticoagulated with warfarin. Microscopic hematuria A. Microscopic hematuria may be discovered by accident when blood (either red blood cells or hemoglobin) is found on urinalysis or dipstick done for other purposes. Although B. C. abnormal hematuria is commonly defined as presence of ≥ 3 RBCs per HPF in spun urine sediment, there is no "safe" lower limit below which significant disease can be excluded. Lowering the cut-off value of RBCs chosen to define hematuria results in a greater number of false positive test results (no underlying abnormality is found). On the other hand, if higher cut-off values are chosen, it is more likely that the test will miss the presence of significant abnormalities. The role of urinalysis in distinguishing glomerular from extraglomerular bleeding is discussed below. Urine dipstick A. The urine sediment (or direct counting of RBC per mL of uncentrifuged urine) is the gold standard for detection of microscopic hematuria. Dipsticks for heme detect 1 to 2 RBCs per HPF and are therefore at least as sensitive as urine sediment examination, but result in more false positive tests. i. Semen is present in urine after ejaculation and may cause positive heme reaction on the dipstick ii. An alkaline urine with pH > 9 or contamination with oxidizing agents used to clean perineum iii. The presence of myoglobinuria B. C. Thus, positive dipstick test must always be confirmed with microscopic examination of urine. Rarely, a very dilute urine result in osmotic lysis of almost all urinary RBCs, resulting in apparently false positive result as dipstick still detects hemoglobin content. This does not constitute false positive test. False negative tests with urine dipstick are unusual; as a result, a negative dipstick usually excludes abnormal hematuria. False negative dipstick tests have been reported in patients ingesting large amounts of vitamin C; the clinical relevance of this observation is unknown. ETIOLOGY 1. Hematuria may be symptom of underlying disease, some of which are life threatening or treatable. The causes vary with age with the most common being inflammation or infection of 2. prostate or bladder, stones, and, in older patients, a kidney or urinary tract malignancy or benign prostatic hyperplasia. Rarely hematuria is factitious, with blood being added to an unwitnessed urine specimen after voiding (from finger stick). Factitious hematuria can be documented by the absence of hematuria in a urine specimen obtained under direct observation. INITIAL EVALUATION 1. 2. 3. As a general principle, hematuria itself is not dangerous unless extraglomerular bleeding is so brisk that it causes clots that obstruct ureter(s). Transient hematuria is common and almost always benign in young patients and cause is often not identified. In contrast, even transient hematuria may be a symptom of underlying serious condition, particularly in patients over age 40 years. The evaluation should address the following three questions A. Are there any clues from Hx or PE that suggest particular diagnosis? B. Does hematuria represent glomerular or extraglomerular bleeding? C. Is the hematuria transient or persistent? 4. Based upon the answers to these three questions, imaging with multidetector CT urography and cystoscopy may be indicated. A. B. 5. CT urography should be performed in all patients with unexplained persistent hematuria (patients without infection, glomerular hematuria, or other known source of hematuria). CT urography should also be performed in patients with transient hematuria who have risk factors for malignancy. Cystoscopy should be performed in all patients with gross hematuria unless there is active UTI or known glomerular hematuria. However, patients who pass blood clots should have cystoscopy even if there is evidence for glomerular hematuria since glomerular lesions do not produce blood clots. Cystoscopy should also be performed in patients with persistent microscopic hematuria if hematuria is unexplained (patients without infection, glomerular hematuria, or other known source of hematuria) and if risk factors for malignancy are present. The role of cystoscopy is uncertain in patients with unexplained persistent microscopic hematuria who have no risk factors for malignancy. Historical clues A. Concurrent pyuria and dysuria, which are usually indicative of UTI, but may also occur with bladder malignancy. B. A recent URI raises possibility of post-infectious GN or IgAN or sometimes hereditary nephritis. C. Unilateral flank pain, which may radiate to groin, suggests ureteral obstruction due to calculus or blood clot, but can occasionally be seen with malignancy. Flank pain that is D. E. persistent or recurrent can also occur in rare loin pain-hematuria syndrome. Symptoms of prostatic obstruction in older men such as hesitancy and dribbling. The cellular proliferation in BPH is associated with increased vascularity, and new vessels can be fragile. There is some controversy about whether hematuria is more common in these patients than in age-matched controls. However, there is general agreement that presence of BPH should not dissuade the clinician from pursuing further evaluation of hematuria, particularly since older men are more likely to have more serious disorders such as cancer of prostate or bladder. Among those with gross hematuria in whom no other cause can be identified, finasteride usually suppresses hematuria. History of bleeding disorder or bleeding from multiple sites due to excessive anticoagulant therapy. However, it should not be assumed that hematuria alone can be explained by chronic warfarin therapy. In one report of 243 patients prospectively followed for 2 years, the incidence of hematuria was similar to that in control group not receiving warfarin. Furthermore, evaluation of patients who developed hematuria revealed genitourinary cause in 81% of cases. Infection was most common, but papillary necrosis, renal cysts, and several malignancies of the bladder were also found. These observations indicate that hematuria in anticoagulated patient should generally be evaluated in the same fashion as in other patients unless there is evidence of bleeding from multiple sites with markedly abnormal coagulation studies. F. G. Recent vigorous exercise or trauma in absence of another possible cause. Family history of renal disease, as in hereditary nephritis, PCKD, or sickle cell disease. H. Cyclic hematuria in women that is most prominent during and shortly after menstruation, suggesting endometriosis of urinary tract. Contamination with menstrual blood is always possibility, and should be ruled out by repeating urinalysis when menstruation has ceased. Medications that might cause nephritis (usually with other findings, typically with renal insufficiency). Black patients should be screened for sickle cell trait or disease, which can lead to papillary necrosis and hematuria. Travel or residence in areas endemic for Schistosoma haematobium or tuberculosis. I. J. K. L. 6. Sterile pyuria with hematuria, which may occur with renal tuberculosis, analgesic nephropathy and other interstitial diseases. Glomerular vs. non-glomerular bleeding A. The identification of glomeruli as source of bleed can optimize subsequent evaluation. In particular, patients with clear evidence of glomerular hematuria may not need to be evaluated for potentially serious urologic disease unless there is some other reason to do so. Although identification of dysmorphic RBC, proteinuria, cellular casts, and/or renal insufficiency warrants nephrologic evaluation, they do not necessarily preclude need for urologic workup. B. Glomerular hematuria may result from immune-mediated injury to glomerular capillary wall or, in noninflammatory glomerulopathy such as TBMD, from localized gaps in glomerular capillary wall. C. Signs of glomerular bleeding (best identified by a nephrologist or other experienced examiner) include RBC casts, dysmorphic RBC, and, in patients with gross hematuria, a brown, cola-colored urine (table 2). Glomerular bleeding is indicated by proteinuria exceeding 500 mg/day that is temporally related to onset of hematuria, however, new onset hematuria in setting of prior chronic proteinuria should elicit consideration of extraglomerular or urologic source. D. Red cell casts i. The presence of RBC casts is virtually diagnostic of glomerulonephritis or vasculitis, ii. although such casts are infrequently seen in AIN. The absence of these casts, however, does not exclude glomerular disease. RBC casts tend to accumulate at edges of coverslip. Thus, one has to examine all of the microscopic fields, initially at low power. Prolonged centrifugation may disrupt cellular casts, diminishing the likelihood of identifying such casts. E. Red cell morphology i. Evaluation of RBC morphology may be helpful in identifying the cause of hematuria. ii. iii. iv. v. vi. The RBC is typically uniform and round with extrarenal bleeding, but usually has dysmorphic appearance with renal lesions, particularly but not only glomerular diseases. This change in morphology is manifested by blebs, budding, and segmental loss of membrane, resulting in marked variability in RBC shape and a reduction in mean red cell size. Red cell injury in this setting may be due both to mechanical trauma as the cells pass through rents in glomerular basement membrane and to osmotic trauma as cells flow through nephron. The small number of RBC in normal urine is also dysmorphic, suggesting glomerular origin. The potential importance of red cell morphology was illustrated in a report in which isomorphic red cells were seen in all 30 patients with non-glomerular bleeding but only 1 of 87 with proven glomerulonephritis. A predominance of normal shaped red cells can occasionally be seen in patients with glomerulonephritis who undergo a forced diuresis or have advanced renal insufficiency or gross hematuria. It has been suggested that the magnitude of dysmorphic hematuria is best expressed in absolute terms rather than as a percentage of urinary red cells. If, for example, only 25% of urinary red cells are dysmorphic but the patient is excreting 100,000 red cells per mL (normal < 8000/mL in centrifuged urine and less than 13,000/mL in uncentrifuged urine), then there are 25,000 dysmorphic red cells per mL, indicating the presence of glomerular disease. However, such quantitative testing is rarely performed in routine practice. Acanthocytes 1. The type of dysmorphic RBC may be of diagnostic importance. In particular, dysmorphic RBC alone may be predictive of only renal bleeding while acanthocytes (ring-shaped red cells with vesicle shaped protrusions that are best seen on phase contrast microscopy) appear to be most predictive of glomerular disease. In one study, for example, the presence of acanthocytes comprising ≥ 5% of excreted red cells had a sensitivity and specificity for glomerular disease of 52 and 98%. Regardless of absolute number or percentage, the presence of acanthocytes in the urine should lead clinician to consider nephrology consultation rather than lengthy urological evaluation. Limitations 1. The major question regarding utility of RBC morphology in determining cause of hematuria is whether the findings in clinical studies can be replicated in clinical practice. Optimal assessment of RBC morphology requires phase contrast microscopy, which is not generally available in a physician's office and requires experience in its use to gain proficiency. 2. 3. The subjective nature of identifying "dysmorphism" is another potential limitation. Acanthocytes (also called G1 cells) may be easier to identify with certainty, even without phase contrast microscopy. However, most physicians do not have expertise in identifying dysmorphic RBC or distinguishing RBC casts from RBC overlying granular casts and most do not have access to phase contrast microscopy. In addition, absence of these findings does not exclude glomerular disease. Proteinuria, if present (2+ or greater on the dipstick, which is then quantified by urine protein-to-creatinine ratio on random specimen) suggests presence of glomerular disease in patients with hematuria. The diagnostic importance of proteinuria varies with time of onset. If patient has previously identified proteinuria well before onset of hematuria, then a separate disease may be responsible for hematuria. As example, if patient with CKD and proteinuria but no hematuria (as in nephrosclerosis) develops new hematuria, it should not be assumed that bleeding is due to initial glomerular disease. Such patients should undergo a full evaluation for hematuria. F. Red to brown urine i. A change in urine color with gross hematuria is additional finding that may be helpful. The urine is typically red to pink with extraglomerular bleeding. Although red urine also may be seen with glomerular bleeding (particularly in alkaline urine), combination of prolonged transit time through nephron and acid urine pH may result in formation of methemoglobin, which has smoky brown or "Coca cola" color. G. Blood clots i. Blood clots, if present, are almost always due to extraglomerular bleeding. They are indicative of heavy focal bleeding in which whole blood is shed into urine in amounts sufficient to support clot formation. ii. The characteristic absence of blood clots with gross hematuria due to glomerular bleeding may be due to one or more of the following factors. 1. The presence of urokinase and t-PA in glomeruli and tubules. 2. Glomerular bleeding is typically diffuse capillary process in which minute amounts of blood are added to relatively large volumes of glomerular filtrate. H. Proteinuria i. As noted above, proteinuria that is temporally related to hematuria is suggestive of glomerular disease. Hematuria alone does not typically lead to significant increase in protein excretion. A dipstick test for protein that is > 1+ is rarely observed with extraglomerular bleeding, even with gross hematuria, unless the amount of gross blood is very large. As an example, as little as 1 mL of blood in one liter of urine can produce a visible color change. This quantity of blood contains approximately 0.6 mL of plasma, which will contain only 35 mg of protein at plasma protein concentration of 6 g/dL (60 g/L). A protein of 35 mg/L is below sensitivity of urine dipstick for protein and therefore will not be detected on routine examination. ii. I. However, a large amount of gross bleeding can cause abnormal proteinuria. Extremely bloody urine, especially with clots, should trigger evaluation for extraglomerular source even if abnormal proteinuria is present. Role of renal biopsy i. The main indication for performing renal biopsy in patients with glomerular hematuria (defined by presence of dysmorphic RBC and/or RBC casts) is the presence of risk factors for progressive disease such as proteinuria and/or elevation in SCr. New onset HTN or significant elevation in BP above previous stable baseline that does not exceed 140/90 mmHg (from 100/60 to 130/80 mmHg) is also associated with greater likelihood of progressive disease, but is primarily seen in patients who also have one or both of the other adverse predictors. ii. iii. iv. Renal biopsy is not usually performed for isolated glomerular hematuria (no proteinuria, no elevation in SCr, no elevation in BP about previous stable baseline, and no systemic manifestations), since there is no specific therapy for these conditions and the renal prognosis is excellent as long as there is no evidence of progressive disease. In addition, management of these patients is not usually affected by biopsy results. In one study, for example, the result of the biopsy altered management in only 1 of 36 patients with isolated hematuria compared with 9 of 28 patients with hematuria and proteinuria (3 vs. 32%). When renal biopsy is performed in such patients, the most common findings are a normal biopsy or one or four disorders: IgA nephropathy, TBMN (benign familial hematuria), mild nonspecific glomerular abnormalities, and hereditary nephritis (Alport syndrome). Among glomerular diseases, IgA nephropathy is the most common cause in Japan. Monitoring if renal biopsy is not performed 1. If renal biopsy is not performed in patient with isolated glomerular hematuria, periodic monitoring is warranted during follow-up to detect progressive disease. 2. In a study in which mass screening for asymptomatic hematuria or proteinuria was performed in over 56,000 adults, 432 had asymptomatic hematuria without proteinuria. At a mean follow-up of 5.8 years, hematuria disappeared in 44%, persisted without proteinuria in 44%, and persisted with the development of proteinuria in 11%. None of the patients developed renal insufficiency, which was defined as a creatinine clearance less than 60 mL/min and/or SCr > 1.5 mg/dL. The prognosis was worse in the 134 patients with asymptomatic hematuria and proteinuria: hematuria disappeared in only 16%; and renal insufficiency developed in 15%. 3. 4. 7. The clinical course of isolated glomerular hematuria was evaluated in a series of 85 patients who were followed for a mean of 43 months. 3 patients developed proteinuria (2 with IgAN and one without biopsy), one developed proteinuria and renal insufficiency (MPGN), and 11 developed HTN (3 with TBMD, two with IgAN, 2 with normal biopsy, one with FSGS, and 3 without renal biopsy). Progressive disease is more common in patients with hematuria due to IgA nephropathy. This was illustrated in a study of 72 consecutive patients with hematuria due to IgAN and no or minimal proteinuria (400 mg/day or less) who were followed for a median of seven years. Progressive disease occurred in 32 patients (44%), many of whom had more than one sign of progression: 24 developed proteinuria of 1 g/day or more; 19 became hypertensive; and 5 developed increase in SCr. 5. Renal biopsy is not indicated in patients with persistent isolated non-glomerular hematuria (no dysmorphic RBC or RBC casts, no proteinuria). Such patients need thorough evaluation with imaging and/or cystoscopy, particularly in patients with malignancy. These issues are discussed below. Transient or persistent hematuria A. There is no cause of low-level hematuria that, in the absence of other signs and symptoms, requires immediate diagnosis. As a result, it is reasonable to repeat an abnormal urinalysis in few days to determine if hematuria is transient or persistent. B. C. D. Transient microscopic hematuria is a common problem in adults. The following observations illustrate the range of findings. i. In a prospective cohort study including 2,421,585 members (of all ages) of a managed care organization with at least one urinalysis, 967,297 (40%) had asymptomatic microscopic hematuria. Of these, a second urinalysis was positive for microscopic hematuria in 643,304 (66%). Thus, approximately one-third of individuals with an initially positive urinalysis had transient hematuria. ii. Another study evaluated 1000 young men who had yearly urinalyses between the ages of 18 and 33 years; hematuria was seen in 39% on at least one occasion and 16% on two or more occasions. Hematuria has also been found in up to 13% of men and postmenopausal women. No obvious etiology can be identified in most patients with transient hematuria. Fever, infection, trauma, and exercise are potential causes of transient hematuria. Transient hematuria can also occur with UTI (cystitis or prostatitis). In this setting, hematuria is typically accompanied by pyuria and bacteriuria and patients often complain of dysuria. A potential source of error is that dysuria (but not pyuria and bacteriuria) can also be seen with macroscopic hematuria from bladder cancer. E. 8. 9. An important exception to typically benign nature of transient hematuria occurs in patients over age 40 years in whom even transient hematuria carries increased risk of malignancy (assuming no evidence of glomerular bleeding as described above). Urine culture A. All patients should have urine culture to exclude infection prior to evaluation of hematuria. Patients who have positive urine culture should be treated for infection with close follow-up. The urinalysis should be rechecked in 6 weeks to determine whether hematuria has resolved. Patients who have resolution of hematuria do not require further evaluation. Urine cytology A. A voided urine specimen should be sent for cytology in patients at increased risk for B. C. urothelial cancers. The sensitivity of urine cytology is greatest for carcinoma of bladder (approximately 90%). By comparison, sensitivity for upper tract transitional cell carcinoma is limited, with the reported false negative rate overall being 65% (and as high as 96% with low grade tumors). Urine cytology is frequently obtained immediately prior to cystoscopy, which is usually performed in patients at risk for malignancy. Among patients at low risk for genitourinary cancer (such as individuals under the age of 40 years without specific risk factors), some investigators recommend that either urine cytology or cystoscopy be performed. Cystoscopy is subsequently done if malignant and/or atypical/suspicious cells are identified. IMAGING 1. Once glomerular bleeding has been excluded in a patient with otherwise unexplained hematuria, the diagnostic workup should include a search for lesions in the kidney, collecting system, ureters, bladder or urethra. The diagnostic yield in adults increases with age and may be higher for gross hematuria than for microscopic hematuria. 2. Multidetector CT urography (CTU) is the preferred imaging study in patients with otherwise unexplained hematuria. Other available modalities include conventional radiography, IVP, retrograde pyelography, ultrasonography, MRI, magnetic resonance urography, and conventional CT scanning. 3. Patients with history of malignancy in bladder or kidneys are at increased risk for malignancy 4. at the other site and should always undergo further evaluation. Preference for CT urography A. Most clinicians consider multidetector CTU to be the preferred initial imaging modality in most patients with unexplained hematuria. This modality may be particularly indicated in those with an increased risk of genitourinary malignancy or disease. The combination of multidetector CTU and cystoscopy, which together provide a complete evaluation of the genitourinary system, should be performed in almost all patients with unexplained hematuria. B. C. D. E. F. G. Multidetector CT urography combines the benefits of conventional CT scanning (with and without contrast) with the ability of an IVP to accurately visualize ureteral and pelvicalyceal surfaces. Although different protocols exist to perform CT urography, images of the kidney and genitourinary system are first obtained pre-contrast; after the administration of contrast, images are then obtained in the renal parenchymal phase, followed by the excretory phase. Thus, multidetector CT urography provides global imaging of GU tract. Compared with other modalities, multidetector CT urography is associated with increased sensitivity and specificity for the detection of renal masses, urinary tract calculi, and pelvicalyceal and ureteric transitional cell carcinomas. Intravenous pyelography – CTU has largely replaced IVP, which is less sensitive in detecting kidney stones and renal masses (particularly small masses). The magnitude of this effect was illustrated in a study of 115 patients with hematuria in which CTU imaging was significantly more sensitive (100 vs. 61%) and specific (97 vs. 91%) than IVP. Despite these observations, some clinicians still perform IVP because of the belief that it is best able to characterize lesions in urothelium. However, increasing evidence suggests that this is not true given that IVP is associated with only 40 to 65% detection rates for urothelial neoplasms. Ultrasonography – Ultrasonography has a lower diagnostic yield and is less sensitive in detecting urothelium transitional cell carcinoma, small renal masses, and calculi. The relative insensitivity of ultrasonography in detecting small renal tumors was best shown in a study in which ultrasonography detected only 26, 60, 82, and 85% of CT-confirmed lesions < 1 cm, between 1 and 2 cm, between 2 and 3 cm, and 3 cm or more in size, respectively. However, the combination of ultrasonography and CT may improve the characterization of renal masses. This is particularly true with smaller sized lesions. The favorable safety profile of ultrasound over CT has led some groups outside of the United States to elect ultrasound as the preferred initial upper tract screening modality. MR urography – MR urography is less able to detect smaller urothelial lesions and non-obstructing stones. In addition, there is limited availability and experience with this technique. However, advances with MR urography may increase the use of this modality in this setting and kidney masses are readily observed. This is an acceptable imaging alternative in patients with contraindications to iodinated contrast administration. Retrograde pyelography – A retrospective study evaluated the accuracy of multidetector CTU and retrograde pyelography in helping diagnose upper urinary tract urothelial tumour in 106 patients. Both multidetector CT urography and retrograde pyelography had sensitivities and specificities of 97 and 93%. H. Radiation dose i. A major concern with CTU is relatively high radiation dose. The average effective ii. iii. dose with contrast-enhanced CTU (7.7 mSv) is more than double that of IVP (excretory urography). As a result, much effort has been devoted to using lower dose protocols or synchronous acquisition of nephrogenic and excretory phase images. Because of the concern about radiation exposure, CTU should not be used in pregnant women. In addition, some centers avoid CTU except in patients with known risk factors for genitourinary malignancies. Although we suggest CTU in all patients with known risk factors for malignancy, some data suggest that non-enhanced imaging in young patients may provide sufficient diagnostic information. As an example, a study of 375 CTU scans performed in patients < 40 years for evaluation of hematuria compared the findings of contrast-enhanced and non-enhanced images (non-enhanced imaging requires less radiation). The non-enhanced images identified 92 of 97 clinically significant findings (95%). 5. Summary A. The choice of initial imaging study in patients with unexplained hematuria may vary with age, presence of comorbid conditions, and the risk of genitourinary malignancy or disease. As mentioned above, multidetector CT urography (CTU) is the preferred initial imaging modality in almost all patients. There are, however, some exceptions to this general recommendation. i. Ultrasonography can be used in the evaluation of pregnant women in whom CTU should not be performed. ii. Some centers restrict the use of CTU to patients > 40 years or to those < 40 years with known risk factors for genitourinary malignancies, due to concerns about the risk of radiation outweighing the risk of disease. With this approach, MR urography or other modalities may be considered. iii. Among patients with a contraindication to iodinated contrast administration, ultrasonography, CT scan without contrast, and MR imaging are alternative modalities. Desensitization is an option in patients with a prior allergy to radiocontrast media. RISK FACTORS FOR MALIGNANCY 1. The American Urological Association (AUA) best practice policy recommendations on asymptomatic microscopic hematuria included the following risk factors for malignancy. A. Age > 35 years B. Smoking history in which risk correlates with extent of exposure C. Occupational exposure to chemicals or dyes (benzenes or aromatic amines), such as printers, painters, chemical plant workers D. History of gross hematuria E. History of chronic cystitis or irritative voiding symptoms F. History of pelvic irradiation G. History of exposure to cyclophosphamide H. I. 2. 3. History of chronic indwelling foreign body History of analgesic abuse, which is also associated with an increased incidence of carcinoma of the kidney The risk factors for bladder and renal cell carcinomas are discussed in detail elsewhere. The importance of gross hematuria and older age was illustrated in several studies. A. In a prospective cohort study of 4414 members of a managed care organization with unexplained, asymptomatic microscopic hematuria who were referred for urologic evaluation, 111 cancers were identified (2.5%); 100 were bladder cancers and 11 were renal cancers. However, the prevalence of malignancy was 11.2% among patients 50 years or older who also had a history of gross hematuria plus at least one additional risk factor (male sex, smoking, or more than 25 red blood cells per high powered field). In contrast, the prevalence of cancer was 0.2% among patients younger than 50 years who did not have a history of gross hematuria. This study suggests that individuals at low risk for malignancy (with none of the risk factors listed above) who have asymptomatic microscopic hematuria may not require a urologic referral. B. In another study of 1930 patients (mean age 58 years, 62% male) who were referred to a Hematuria Clinic because of gross or microscopic hematuria, 12% had bladder cancer, 0.7% had kidney and upper tract tumors, and 61% had no cause identified. In addition. i. At age 50 to 59 years, malignancy was identified in 20.4 vs. 1.9% of men with macroscopic vs. microscopic hematuria, respectively, and in 8.9 vs. 1.9% of women ii. with macroscopic vs. microscopic hematuria. At age 60 to 69 years, malignancy was found in 28.9 vs. 7.9% of men with macroscopic vs. microscopic hematuria, and 21.1 vs. 4.5% of women with macroscopic vs. microscopic hematuria. C. 4. Another report evaluated 1034 patients with microscopic hematuria who had more than five red cells per high power field on at least one of three screening urinalyses. All patients were evaluated by ultrasonography, intravenous pyelography (IVP), urinary cytology, and cystoscopy. The incidence of malignancy (bladder, kidney, or prostate) was 2.4%. Among the remaining patients, 20% had kidney stones or glomerular or other intrinsic renal disease, while 78% had either no identifiable cause or a minor lesion such as benign prostatic hypertrophy. Neither cytology nor IVP reliably detected all of the tumors. Ultrasonography was highly accurate for renal tumors, while cystoscopy was required to reliably diagnose bladder or prostatic cancers. Tumors were more common in men and all but one occurred in patients > age of 50 years. An important exception to the typically benign nature of transient hematuria occurs in patients at high risk for malignancy, in whom even transient hematuria carries an appreciable association with malignancy (assuming no evidence of glomerular bleeding as described above). As an example, screening studies limited to healthy men over the age of 50 to 60 years found that 8 to 9% of patients with intermittent asymptomatic hematuria, as detected by a dipstick for heme, had a urinary tract malignancy. CYSTOSCOPY 1. Cystoscopy is associated with the following benefits. A. The entire bladder can be visualized for malignancy or other abnormalities. In the presence of concomitant prostatic hypertrophy, it may be difficult to visualize the entire bladder with video-assisted flexible cystoscopy under local anesthesia. If concerns 2. 3. persist, rigid cystoscopy under spinal or general anesthesia may be required. Analgesic abusers also have an increased incidence of carcinoma of the kidney. B. Cystoscopy may identify the source of the bleeding among patients with gross hematuria. It may be possible to determine if the bleeding is originating from the bladder or from one or both ureters. Unilateral bleeding may be due to an arteriovenous malformation, fistula, venous varices, or unilateral renal or upper urinary tract tumors or stones. C. Cystoscopy is the only modality that permits visualization of the prostate and urethra. Gross hematuria A. All patients who have gross (macroscopic) hematuria and no evidence of either glomerular disease or infection should undergo cystoscopy since it permits direct visualization of bladder and can detect malignant or other sources of bleeding. B. Patients who have gross hematuria with blood clots should have cystoscopy even if they have evidence of a glomerular lesion since blood clots are virtually never associated with glomerular bleeding. Thus, the presence of blood clots in a patient glomerular bleeding suggests the presence of disease in the upper or lower collecting system. Microscopic hematuria A. All patients with microscopic hematuria who have no evidence of glomerular disease, infection, or a known cause of hematuria such as exercise and who are at increased risk for malignancy should undergo cystoscopy. B. The diagnostic yield of cystoscopy is lower in patients who have microscopic hematuria, negative imaging, negative urine cytology, and are at low risk for malignancy. For such patients, the American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines do recommend cystoscopy; given its low morbidity, we discuss the risks and benefits of cystoscopy with all such patients. SCREENING FOR A SECOND LESION 1. There is a field cancerization effect for urothelial tumors. Thus, among patients with hematuria who first undergo cystoscopy and are found to have a bladder tumor, the upper tracts should also be evaluated with imaging study for possible lesions in renal pelvis or ureter, which also have transitional epithelium. On the other hand, patients who are found to a renal pelvic or ureteral cancer with an imaging study should undergo cystoscopy. In a report of 130 consecutive patients who underwent surgery for a renal pelvic cancer, 66 (51%) had a bladder cancer. The bladder cancer occurred before the renal pelvic cancer in 37, after the renal pelvic cancer in 25, and synchronously in 4. UNEXPLAINED HEMATURIA 1. If no diagnosis is apparent from the history, urinalysis, radiologic imaging tests, or cystoscopy, then the most likely causes of persistent isolated hematuria are a mild glomerulopathy and a predisposition to stone disease, particularly in young and middle-aged patients. 2. Glomerular disease A. Although any glomerular disease may be associated with hematuria, most patients also have other signs such as proteinuria, red cell casts, or renal insufficiency. When persistent glomerular hematuria is essentially the only manifestation of glomerular disease, one of four disorders is most likely. i. IgA nephropathy, in which there is often gross hematuria, and sometimes a positive family history but without any clear pattern of autosomal inheritance. ii. Thin basement membrane nephropathy (also called thin basement membrane disease or benign familial hematuria), in which gross hematuria is unusual and the family history may be positive (with an autonomic dominant pattern of inheritance) for microscopic hematuria but not for renal failure. iii. Mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis without IgA deposits. iv. Alport syndrome (hereditary nephritis), in which gross hematuria can occur in B. association with a positive family history of renal failure, and sometimes deafness or corneal abnormalities. In three series of 240 patients with isolated microscopic hematuria, no proteinuria, a normal serum creatinine concentration, and, in two studies, a negative radiologic and cystoscopic evaluation, IgA nephropathy was present in 20 to 30%, thin basement membrane disease in 4 to 43%, and, in one study, mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis without IgA deposits in 10%. In one of these reports, 86% of patients with hematuria persisting for four years had either IgA nephropathy or TBMN. C. 3. 4. Postinfectious glomerulonephritis and exercise are other causes of isolated glomerular bleeding. The hematuria in these settings is typically transient, not persistent as in the above disorders. D. The distinction between glomerular and extraglomerular bleeding and the indications for renal biopsy in patients with glomerular hematuria are discussed above. Hypercalciuria and hyperuricosuria A. As many as 30 to 35% of children with apparently idiopathic hematuria (no proteinuria or infection, negative radiologic evaluation) have hypercalciuria, while 5 to 20% of children with recurrent hematuria have hyperuricosuria; both disorders are often associated with a positive family history (as high as 40 to 75%) of stone disease. These children are at increased risk for the future development of kidney stones. Lowering calcium excretion with a thiazide diuretic typically leads to resolution of the hematuria among those with hypercalciuria; a restricted purine diet or the administration of allopurinol commonly eliminates uricosuria and hematuria in those with hyperuricosuria. B. Similar findings may be present in adults. Some patients have hypercalciuria or hyperuricosuria (as detected by a 24-hour urine collection), while others have a history suggestive of stone disease without these biochemical abnormalities (although citrate excretion was not measured in this study). Treatment with a thiazide diuretic for hypercalciuria or allopurinol for hyperuricosuria usually leads to disappearance of the hematuria. Rare conditions A. Rare causes of hematuria include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasis, radiation cystitis, schistosomiasis (which is not rare in endemic areas), arteriovenous malformations and fistulas, nutcracker syndrome, and the loin pain-hematuria syndrome. Arteriovenous malformations, nutcracker syndrome, and loin pain-hematuria syndrome will be briefly reviewed here; the other conditions are discussed separately. B. Arteriovenous malformations and fistulas i. An AVM or AVF of urologic tract may be either congenital or acquired. The primary presenting sign is gross hematuria, but high-output heart failure and hypertension also may be seen. The latter is presumably due to activation of the renin-angiotensin system resulting from ischemia distal to AVM. ii. The diagnosis may be suspected if there is an irregular filling defect on intravenous pyelography due to compression of the pelvis or calyx. The presence of an AVM can be confirmed by arteriography (which demonstrates almost immediate visualization of the inferior vena cava) or CT scanning. There are several therapeutic options. It is often possible for an experienced radiologist to embolize the lesion at the time of arteriography by the injection of absolute ethanol, steel coils, gelatin sponges, or balloons. Absolute ethanol may be safest; it denatures proteins in the vessel wall, leading to a coagulum that occludes the lumen. Surgery or nephroscopy can be performed if embolization is ineffective or the hematuria recurs. C. Nutcracker syndrome i. The nutcracker syndrome refers to compression of the left renal vein between the ii. aorta and proximal superior mesenteric artery. Nutcracker syndrome can cause both microscopic and gross hematuria, primarily in children (but also adults) in Asia. The hematuria is usually asymptomatic but may be associated with left flank pain. Nutcracker syndrome has also been associated with orthostatic proteinuria. The diagnosis of nutcracker syndrome is established by Doppler ultrasonographic assessment of left renal vein diameter and peak velocity or by magnetic resonance angiography or renal venography. For patients who require treatment because of recurrent or persistent symptoms, a variety of therapies have been used, including stent placement in the left renal vein, transposition of the superior mesenteric artery or left renal vein, and autotransplantation of the left kidney. In a 2007 review of 20 patients who required intervention, stenting was performed in 15, which has the advantage of minimal invasiveness, and transposition of the superior mesenteric artery or left renal vein in five. D. Loin pain-hematuria syndrome i. The loin pain-hematuria syndrome is a poorly defined disorder characterized by loin or flank pain that is often severe and unrelenting, and hematuria with dysmorphic red cell features suggesting a glomerular origin. Affected patients usually have normal kidney function. This disorder is discussed elsewhere. FOLLOW-UP AFTER INITIAL NEGATIVE EVALUATION 1. 2. A cause for hematuria is often not identified. Patients who have a negative evaluation for hematuria generally require follow-up with cytology, urinalysis, blood pressure monitoring, and in some cases with repeat imaging and cystoscopy. The necessity for repeat imaging and cystoscopy largely depends upon whether hematuria was transient or persistent, and upon the patient's risk for malignancy. Follow-up of patients with transient hematuria A. Patients who have even one episode of hematuria and are at high risk for malignancy require close follow-up following a negative evaluation. It is not clear whether obtaining surveillance urine cytology provides a benefit in detecting malignancy. The yield appears to be quite low. In a cohort of 182 patients with asymptomatic microscopic hematuria B. and a median age of 60 years, the first cytology resulted in detection of bladder cancer in four cases, the second identified one additional case, and the third identified no additional cases. Thus, it is reasonable to follow such patients with asymptomatic transient microhematuria and negative urologic workup but who are at risk for malignancy with annual urinalyses. After two consecutive negative urinalyses, this follow-up may be concluded. If gross hematuria occurs at any time after the initial evaluation, the full evaluation should be repeated. C. 3. If hypertension, proteinuria, an increase in serum creatinine, or evidence of glomerular bleeding develops in a patient who has been evaluated for hematuria, the patient should be reevaluated for renal disease. Follow-up of patients with persistent hematuria A. Potentially the most serious disorder in the patient with unexplained persistent hematuria is the presence of an undiagnosed carcinoma of the urinary tract. The combination of a negative CT urogram, negative cytology, and negative cystoscopy is usually sufficient to exclude malignancy in the urinary tract. However, the cause will subsequently become evident in some patients with careful follow-up. In a series of 421 patients with unexplained, asymptomatic microscopic hematuria who were followed at six month intervals for more than one year, approximately 5% had an identifiable cause for hematuria within three years and approximately 1% had a detectable urinary tract malignancy. B. As a result, monitoring with annual urinalyses is recommended for patients with asymptomatic microhematuria; if persisting for three to five years, repeating the initial urologic workup is a reasonable consideration. Some physicians also recommend repeat ultrasonography and cystoscopy at one year in high-risk patients. SCREENING FOR HEMATURIA 1. Screening for hematuria in patients who have no symptoms suggestive of urinary tract disease is not recommended. The most plausible argument for screening would be for the early detection and treatment of cancers of the kidney, collecting system, or bladder in older adults. However, these and other diseases causing hematuria do not meet basic criteria for screening: the prevalence of undetected, asymptomatic, early disease is relatively low (<2%); there is little evidence that hematuria is a sensitive test for localized disease; and there is little evidence in patients with renal cancer that early treatment of local disease results in a better prognosis. 2. Thus, expert groups such as the United States Preventive Services Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination do not recommend screening for hematuria. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS 1. Hematuria is common. In many patients, particularly young adult patients, the hematuria is transient and of no consequence. However there is an appreciable risk of malignancy in 2. patients over age 35 years with hematuria, even if transient. Hematuria may be grossly visible (macroscopic hematuria) or detectable only on urine examination (microscopic hematuria). Microscopic hematuria is defined as the presence of three or more RBCs per high power field in spun urine sediment. Dipsticks for heme detect 1 to 2 RBCs per high power field and are therefore at least as sensitive as urine sediment examination, but result in more false positive tests. A positive dipstick test should be confirmed with microscopic examination of the urine to avoid an unnecessary initiation of a more invasive workup. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. All patients should have a urine culture to exclude infection prior to evaluation of hematuria. Patients who have a positive urine culture should be treated for infection with close follow-up. The urinalysis should be rechecked in six weeks to determine whether hematuria resolved. Patients who have resolution of hematuria do not require further evaluation. A glomerular source of bleeding is suggested by the presence of proteinuria, an active sediment on urinalysis (red cell casts, dysmorphic red blood cells) and renal insufficiency. However most physicians do not have expertise in identifying dysmorphic red cells or distinguishing red cell casts from red cells overlying granular casts. In addition, the absence of the findings does not exclude glomerular disease. Thus, proteinuria, if present, is the most reliable indicator of glomerular disease in patients with hematuria. However, if the patient has previously identified proteinuria before the onset of hematuria, then a separate disease may be responsible for the hematuria. The identification of dysmorphic red blood cells, proteinuria, cellular casts, and/or renal insufficiency warrants a nephrologic evaluation but does not preclude the need for a urologic workup. An imaging study of kidney and collecting system should be obtained for all patients with gross or microscopic hematuria who have no evidence of glomerular bleeding, or infection or other known cause for hematuria. Multidetector CT urography (CTU) is the preferred initial imaging modality in most patients with unexplained gross or microscopic hematuria. Multidetector CTU should not be used in pregnant woman; ultrasonography may be used in the evaluation of pregnant women. A CTU requires intravenous but not oral contrast. Among patients with a contraindication to iodinated contrast administration, ultrasonography, CT scan without contrast, and MR imaging are alternative modalities. Cystoscopy should be performed on all patients with gross hematuria who have no evidence of glomerular bleeding or infection. Patients who have blood clots should have cystoscopy even if they have evidence of a glomerular lesion since blood clots are virtually never associated with glomerular bleeding and would suggest the presence of two separate lesions in the glomerulus and in the upper or lower collecting system. Cystoscopy should be performed on all patients over 35 years with microscopic hematuria after ruling out benign causes, such as infection, menstruation, vigorous exercise, medical renal disease, viral illness, trauma, or recent urological procedures. Cystoscopy should also be performed in those patients with microscopic hematuria who are at increased risk for malignancy, regardless of age. There is a field cancerization effect for urothelial tumors. Thus, among patients with hematuria who first undergo cystoscopy and are found to have a bladder tumor, the upper tracts should also be evaluated with an imaging study for possible lesions in the renal pelvis or ureter, which also have transitional epithelium. Similarly, patients who are found to have a renal pelvic or ureteral cancer with an imaging study should undergo cystoscopy. 9. A cause for hematuria is often not identified. Patients who have a negative evaluation for hematuria require follow-up with annual urinalysis and blood pressure monitoring; in some cases, repeat imaging and cystoscopy may be elected. The necessity for repeat imaging and cystoscopy depends upon whether hematuria was transient or persistent, microscopic or gross, and upon the patient's risk for malignancy. We suggest the following approach. A. Patients with persistent microhematuria and risk factors for malignancy should be offered cystoscopic and imaging reevaluation in 3 to 5 years from their initial presentation. In those with irritative symptoms, tobacco, or chemical exposure, cytology may be useful. We do not recommend any urine markers for routine use. B. New gross hematuria should prompt a reevaluation without delay.