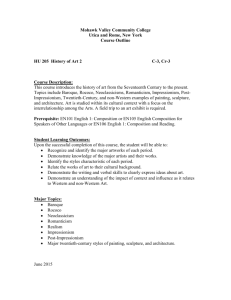

CHP. 20- Romanticism: The 18th and Early 19th Centuries

advertisement

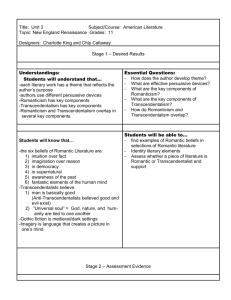

[CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] P A G E |1 Overview Painting ideas set "long ago in faraway places" encompassed a variety of past styles considered first modern art movement The Romantic Movement (from my we) Emphasized democratic attitudes Created for the people of the time Looked toward the future Used dynamic color; fluid, irregular curves; exotic subjects Showed disdain for lofty messages ideas set "long ago in far away places" encompassed a variety of past styles considered first modern art movement Edmund Burke philosopher and social critic who wrote about the "sublime" he saw unfinished and preparatory works as superior to finished works because they allowed a viewer to include their own thoughts Comparison of Neoclassicism and Romanticism Neoclassicism: Rational Romanticism: Emotional Romanticism Romanticism emphasized democratic attitudes It was meant to be art and literature created for and by contemporaries Unlike Neoclassicisms, which looked to the past, romanticism was an art of the present – looking toward the future rather than the past Whereas Neoclassicism emphasized lofty, unpredictable, rational virtues, Romanticism maximized dynamic color, fluid, irregular curves, and exploited exotic subjects while showing disdain for lofty messages Key word for Neoclassicism – rational Key word for Romanticism – emotional Romanticism placed emphasis on sensitivity, passion, subjective, personal experience, and human feelings in general. Eugene Delacroix, a French romantic painter, combined an emotional approach with almost brutal realism-which was a quality unthinkable to the contemporary Neoclassicists, such as David and Ingres Ingres, in fact, considered Delacroix the devil incarnate while Delacroix labeled Ingres paintings as tinted drawings To further anger the Romantics, Ingres referred to Rubens, the hero of the Romantic artists as “That Flemish meat merchant” Although Neoclassicism and Romanticism were radically different in style- one rational and the other emotional-they had one vital tendency in common-namely the preference for what were considered important subjects and interesting stories or events Neoclassical and Romantic artists shared a conviction that only certain elevate, exotic or unusual subjects were fit themes for painting, and generally looked upon the world as divisible into the significant and the commonplace. Both schools considered everything that was ordinary or prosaic as unfit for artistic treatment, but that changes with the Realists. [CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] P A G E |2 Part 6: Unit Exam Essay Questions (from previous Art 261 tests) Compare the Romantic movement with Neoclassicism. How are they similar? What are the differences? (Rubenistes or Poussinistes?) Using your text, study these two paintings and the artists who created them: 1. The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus Peter Paul Rubens 1617 2. The Burial of Phocion Nicolas Poussin 1648 Choose the painting you like most. Analyze it in terms of subject, technique, and space. Be prepared to discuss how you made your choice. .Must be written in essay form—not just an outline. Should be approximately 250–300 words. (from AAT4) Compare the Romantic movement in art and literature with Neoclassicism. How are they similar? What are the differences? Discuss the new developments in the field of psychology and their relationship to nineteenth-century Romanticism. How does Goya create sympathy with or aversion to his painted figures? Use examples from this chapter. What qualities of Romanticism can you identify in Cole, Hicks, and Goya? Characterize what is meant by "sublime," and discuss the qualities of the sublime in Friedrich's Two Men Contemplating the Moon. Discuss how Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People combines allegory with politics. Learning Goals (AAT4) After reading Chapter 20, you should be able to do the following: Identify the works and define the terms featured in the chapter Analyze transformations in views of nature during the Romantic era Discuss Romantic music and literature in Europe and America Trace the history of France from the abdication of Napoleon Bonaparte to the abdication of Louis-Napoleon Describe the revival of architectural styles during the Romantic era Compare watercolor to oil painting and tempera Describe the political subtexts of Romanticism Discuss the French salon Compare Delacroix with Ingres Consider Goya's humanism Describe the aesthetic of the sublime and its relation to Romantic art Describe Sturm und Drang and its relation to German art Compare American landscape painting to European landscape painting Chapter Outline (AAT4) ROMANTICISM: THE LATE 18th AND EARLY 19th CENTURIES Music and poetry; architectural revival styles Burke on the Sublime (1757) Artists England: Blake; Constable; Turner France: Rude; Géricault; Delacroix Germany: Friedrich Spain: Goya American Transcendentalism: Emerson; Thoreau [CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] P A G E |3 Painters in the United States: Cole; Bingham; Bierstadt; Catlin; Hicks Summary and Study Guide Define or identify the following terms: AAT4 Key Terms aquatint a print from a metal plate on which certain areas have been "stopped out" to prevent the action of the acid. binder, binding medium a substance used in paint and other media to bind particles of pigment together and enable them to adhere to the support. gouache an opaque, water-soluble painting medium. ground in painting, the prepared surface of the support to which the paint is applied. luminism an American nineteenth-century art style emphasizing the effect of light on landcape. monolith a large block of stone that is all in one piece (i.e., not composed of smaller blocks), used in megalithic structures. rosin a crumbly resin used in making varnishes and lacquers. wash a thin, translucent coat of paint (e.g., in watercolor). watercolor (a) paint made of pigments suspended in water; (b) a painting executed in this medium. Chronology Art Works know these works by sight, title, date, medium, scale, and location (original location also if moved) and be able to explain and analyze these in relation to any concept, term, element, or principle Summary and Study Guide Late 1700’s to Mid 1800s The Rococo, Enlightenment, Neoclassicism and Romanticism (AP Art History) Terms be able to identify these by sight, explain these in relation to art, and know an example of each in relation to a work of art Rococo archeology Enlightenment Johan Joachim Winckelmann philosophes Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Art in Painting and salon Sculpture by Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1755) Encyclopédie by Denis Diderot (1713‐1784) History of Ancient Art by Johann Joachim Winckelmann the Grand Tour (1764) Industrial Revolution Napoleon Bonaparte (1769‐1821) fête galante Romanticism [CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] P A G E |4 Poussinistes age of revolutions (American, French, and Greek) Rubénistes Crenellation Madame de Pompadour the great rivals: Ingres vs. Delacroix Prix de Rome the Salon Neoclassicism Delacroix’s trip to North Africa and journals excavations at Herculaneum (begun in 1738) and Pompeii Hudson River School (begun in 1748) Art Works know these works by sight, title, date, medium, scale, and location (original location also if moved) and be able to explain and analyze these in relation to any concept, term, element, or principle The growing appreciation for a more natural style Vigée‐Lebrun, Self‐Portrait, 1790, oil on canvas l on canvas 5’ 5/8”. which a lamp is put in place of the sun), c.1763¬1765, oil on canvas Copley, Portrait of Paul Revere, c.1768‐1770, oil on canvas lottesville, Neoclassicism in Franc , The Coronation of Blake, Ancient of Days, frontispiece of Europe: A Prophecy, 1794, hand colored etching Francisco Goya, Saturn Devouring His Children, 1819‐1823, detail of a detached fresco on canva 818‐1819, oil on le, 1830, oil on canvas A grand sculpture for the Arc de Triomphe 1833‐1836, limestone –La Marseillaise, Arc de Triomphe, Paris, (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On), 1840, oil on canvas ssouri, c.1845, oil on canvas [CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] P A G E |5 This New Thing Called Pho (*Nadar and O’Sullivan took their pictures and produced the negatives in the year listed, the print from this negative however was made more recently by some other dude.) 1. The Rococo Style Rococo art was the art of a particular social class—the aristocracy—and it was an art devoted solely to pleasure. Louis Vav had set the stage for this art when he centralized the rule of his country, bringing all the nobles to Versailles (Figure 19 67) from their country estates, thus transforming them from semi independent administrators to dependent courtiers. All were dependent on the will of the king and their fortunes depended on their ability to please. While the older courtiers played the pompous game of flattery at Versailles, the younger ones became increasingly restive with the seriousness and formality of the whole affair. Having no real function to perform for society, they devoted themselves to the pursuit of pleasure, and they developed it into a fine art. Women came to play a central role in this pursuit, as well as in eighteenth century society and art patronage. The Rococo style itself is often considered to be feminine in contrast to the masculine style of Louis XIV. Typical of the period is the figurine of Madame de Pompadour (Figure 20 7) the mistress of Louis XV and a dominant figure in the court life of her time. Compare it to the portrait of Louis XIV (Figure 20 3). The figurine of Madame de Pompadour has none of the pompous formality of that of Louis. She is shown as Venus, the goddess of love. The scale is small, and the mood is delicately playful and charming, rather than reflecting the grandeur sought by Louis XIV. This young woman had been put in training since her infancy to become mistress of the king after a gypsy predicted she would have that fate. At a masked ball held at Versailles in 1745 the king, dressed as a yew tree, met her for the first time. Within a few months, she had become his official mistress, a position she held for twenty years. She wielded considerable power behind the throne and was a generous supporter of artists and writers. Even after he had turned to other women, she remained the king's best friend and closest confidante. She saw her role as the provider of constant distractions for the king and she did it superbly. A portrait of Madame de Pompadour painted by Boucher shows her in a casual moment, looking up from a book she had been reading. The portrait was done in the pastel colors favored by Rococo artists. You might wish to compare the pastel portrait of the Cardinal de Polignac by Rosalba Carriers (Figure 20 29) with the Rubens' Baroque portrait of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel (Figure 19 43) done one hundred years earlier to illustrate the change to more informal portraiture during the eighteenth century. The shift from the formal to the informal noted in portraiture is echoed in the architectural change as can be seen from the comparison of grandiose buildings like Versailles Palace (Figure 19¬65) with more intimate buildings of the Rococo. Although the Rococo style began in France, during the course of the eighteenth century it spread to many of the courts of Europe. Perhaps the most outstanding examples of Rococo architecture were built in Germany, with the gem being the Amalienburg (Figure 20 9) built in the park of the Nymphenburg Palace in Munich. The scale is small and the emphasis was on intimacy and convenience. The exterior of the building utilizes the bombe curving facade that adds a delicate grace to the building. The delicacy and gaiety of the Rococo style makes itself felt most obviously in the interiors of the building. The dining room, with its reflecting mirrors and delicate curvilinear decoration (Figure 20 14), can be compared to the majestic and somewhat overwhelming Galerie des Glaces, or Hall of Mirrors from Versailles (Figure 19 68). The Rococo preferred asymmetry and delicate silver to the symmetry and heavy gilding used in so much Baroque decoration. The charming salon from the Hotel de Soubise in Paris shown in Figure 20 2 is typical of the rooms that members of eighteenth century French society loved to frequent. These rooms were the center of small but brilliant social gatherings where wit and grace were prized above all virtues. As the authors of the text say, WThe Rococo is essentially an interior style; it is a style of predominately small art." As architecture became smaller in scale, the sculpture and painting intended to decorate it became smaller and more intimate as well. Classical themes continued to be popular, but they took on a different meaning. No longer was homage paid to the great deities, but rather to smaller ones. The seventeenth century group of Apollo and the Muses (Figure 19 73) made for a grotto in the gardens of Versailles, consisting of life sized figures, a stately, impressive grouping that symbolizes the arts and their inspiration. The typical Rococo statuette shown in Figure 20 6 shows a satyr and a nymph playing on a see saw, hardly an inspirational subject, but really quite delightful. Classical scenes of conflict like Pierro Puget's seventeenth century version of Milo of Crotona in Figure 19 72 gave way to gentle themes like Falconet's Venus of the Doves in Figure 20 7, which, as we have seen, was a portrait of one of Louis XV's mistresses, Madame de Pompadour. Poussin's moralistic landscape paintings, like the one in Figure 19¬61, which shows the burial of the classical hero of Phocion, gave way to landscapes of pure pleasure, like the Return from Cythera shown in Figure 2G16. Elegant aristocrats are shown preparing to return from an outing on the fabled island of Cythera, the Greek island of love. Venus' statue is shown on the right wreathed in flowers, while fat cupids circle the [CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] P A G E |6 elegantly decorated boat on the left. These paintings of aristocratic parties were known as "Fetes galantes." This work was painted by the greatest master of the fete galante, Antoine Watteau. Although he is the most famous painter of the eighteenth century aristocracy, he was himself from the lower classes. It was only with the greatest difficulty that his parents managed to give him the education he needed to become a painter. He got to know the guard at the Luxembourg Palace in Paris who he persuaded to let him in to see the paintings that Rubens had done for Maria de' Medici. He studied the Flemish master and many feel improved on his coloring. He even went further than had Rubens in loosening his brushwork and his glancing, shimmering lights are forerunners of the Impressionist brushstroke. L'Indifferent (Figure 20 15) demonstrates his exquisite handling of the brush, the glancing white lights that make the satin ripple and glow, and the marvelous sense of airy atmosphere he gets in the background. Watteau's successors never quite matched his taste and subtlety. The most famous painter of the mid eighteenth century was Francois Boucher, the favorite of Madame de Pompadour. Boucher became her chief stage designer and master decorator. In his paintings the female figure triumphs, women, alluringly undressed, are everywhere, as you see in the image of Cupid a Captive (Figure 20 5). Pierre Schneider feels that the ladies Boucher represents cannot altogether disguise their real occupation, for a trace of vulgarity lurks beneath their elegance. The nymphs and divinities are opera girls (a bit like the show girls of our time) in disguise. One of his contemporaries observed that "Boucher had not seen the graces in the right sort of places." Boucher served as teacher to the last of the great Rococo painters, Jean Honore Fragonard, whose painting The Sunng is shown in Figure 20 4. His brilliant but impatient pupil won the prix de Rome on his first try in 1752. Boucher had some apprehension about how Fragonard would react to Rome and warned him, "If you take Michelangelo and Raphael seriously, you are a lost fellow." While in Rome he became more interested in the work of Baroque painters like Pietro da Cortona, whose painterly approach was more like his own. On his return from Rome, he joined the Academy and tried doing noble pictures, but they were dismal failures. Instead he decided to do the more saleable frivolous subjects. This painting is certainly frivolous, for it shows a young man enjoying a special view of the young woman on the swing. The following story explains the somewhat singular composition. A rich personage had called in the painter called Doyen, and pointing to a young woman with whom he was clearly on terms of intimacy, he explained to the artist that he would like him to depict her soaring high on a swing pushed by a bishop while he himself would be reclining in the grass, savoring the spicy spectacle of her flying skirt. Doyen was taken aback, not so much by the nature of the request as by the fact that it should be addressed to him, a painter of religious scenes. He referred the man to Fragonard, with the result that you see. Fragonard's style was well adapted to such scenes—his lightness and mobility tell the story with a frivolity and superficiality that seems to sum up his age. Although the Rococo was essentially a secular style, a number of German architects made great use of it in a series of spectacular eighteenth century churches built in Bavaria, such as Neumann's pilgrimage church of Vierzehnheiligen, which commemorated the fourteen saints who had appeared miraculously to a local shepherd (Figure 20 15). The Bavarian pilgrimage churches owe more to the Italian buildings of Borromini and Guarini than to the French, and in many ways they can be considered as a mixture of Baroque and Rococo. The undulating facade of the exterior owes much to the Italians, but the interior (Figure 20 16) is more delicate than the Italian examples. There seem to be no straight lines, and even the entire plan is made up of interlocking ovals (Figure 20 18). The German decorators sometimes got carried away with details such as the shrine in the center that almost seems like a candy confection. The Asam brothers created a series of churches that combined incredibly rich decoration with a dramatic type of illusionistic theater. In the Assumption of the Virgin from the monastery church at Rohr (Figure 20 19) we see a German version of the sacred theater so well presented by Bernini almost a hundred years earlier (Figure 19 12). The stone figure of the virgin seems weightless as it is borne aloft by the angels. Here we see a final statement of the triumphant Catholicism put forth by the Council of Trent. The triumph of the Virgin Mary is reasserted in both palpably physical and transcendently spiritual terms. These Bavarian churches were often painted with ceiling frescoes, many of which emulated the work of Tiepolo, the last of the great Italian painters to have an international impact. One of his ceilings illustrated in Figure 20 14 is from the villa of an Italian family, and shows their apotheosis. He travelled to many of the courts of Europe, painting frescoes that recalled the great Italian Baroque ceilings but with a much lighter touch. Neumann and Tiepolo collaborated to create the masterpiece in the Bishop's palace or Residenz at Wurzburg. Neumann designed the building and the magnificent staircase while Tiepolo did the ceiling above using the theme of the four continents. Suggested Images: Figures 19 12, 19 43, 19 61, 19 65, 19 68, 19 72, 19 73, 20 1, 20 2, 20 3, 20 4, 20 5, 20 6, 20 7, 20 8, 20¬9, 20 10, 20 12, 20 14, 20 15, 20 16, 20 17, 20 18, 20 19, 20 20, 20 29 [CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] P A G E |7 2 The Art of the Elghteenth Century Bourgeoisie The aristocrats who commissioned the charming Rococo decorations were not the only eighteenth century patrons of the arts. During the eighteenth century wealthy members of the bourgeoisie came to take an ever more important role in both politics and society, and the works of art they bought were not those favored by the aristocracy. The greatest painter of the eighteenth century bourgeoisie was Jean Baptiste Chardin, who is remembered for still lifes and for scenes such as the one illustrated in Figure 20 26. Chardin's quiet compositions are closest to those of the great seventeenth century Dutch Master Vermeer (Figure 19 54), who also painted for bourgeoise patrons. Chardin's colors are a bit warmer than Vermeer's, but the work of both artists breathe a serenity that sets them off from the work of other contemporary painters. Both found great pleasure in the quiet beauty of simple things, and both imbued the commonplace with an uncommon dignity. In Chardin's simple but monumental composition of Grace at Table (Figure 20 26) Chardin has organized all the elements of his composition into a stable monumental pyramid, yet the woman looks completely natural and at ease as she bends over the table, setting food before the children. The composition contains a number of his favorite colors and textures; the whites of clean linens, the warmth of garments, and above all the soft glow of copper. The theme of simple piety and homey virtues reflects the values of the middle class. This simple composition is quite different from all the fancies of the contemporary Rococo. It is hard to imagine that Chardin was working in the same period and in the same country as Boucher and Fragonard. The simple piety of Chardin becomes moralistic preaching in the works of Jean Baptiste Greuze (Figure 20 37). This work, called The Wicked Son Punished, is part of a series devoted to the prodigal son. The dramatic poses and histrionic gestures are undoubtedly influenced by the exaggerated gestures of the theater, which was extremely popular in the eighteenth century. Compare this scene with the quiet but deeply moving joy with which Rembrandt's aged father welcomes home his wandering son (Figure 19 50). By contrast Greuze shows the son's punishment, for the son comes home to find the father dead and the rest of the family in hysterics. The work gives a moral sermon, and although most of us tend to recoil a bit from this sort of over done moralism, it was quite possibly a necessary antidote to the excesses of Rococo eroticism. When Louis XVI, who was moral to the point of prudishness, came to the throne in 1774 he ordered Boucher's erotic paintings destroyed. Greuze became the painter of the day, for his work was considered to inspire virtue. Moralistic art existed in eighteenth century England as well, but it was of a somewhat less hypocritical nature than much of Greuze's productions. For example, consider the work of William Hogarth, whose moralism was always spiced with satire. His work, like Figure 20 36, shows the influence of the eighteenth century theater, just as did that of Greuze. This is one of the scenes from his famous series known as Marriage a La Mode, dealing with a common eighteenth century situation: the marriage of a bourgeois girl to an aristocrat because her parents are after his title and he is after their money. This episode shows the breakfast scene in which both husband and wife are exhausted after a long night in someone else's company. In another episode a young girl is taken to a quack for treatment for the venereal disease she has contracted from the dissolute husband, while in another the husband returns home to find his wife's lover fleeing out the window and kills him. Such genre paintings are closely related to the comedies of rnanners so popular in eighteenthcentury theater. Moralistic messages were also delivered in the Neoclassic guise that became popular later in the eighteenth century. Angelica Kauffmann's painting of Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi (Figure 20¬39), illustrates the popular mode of presenting a model of virtue or exemplum virtutis from the literature of Greece and Rome. Although presenting a classical theme, Kauffmann's style showed the stylistic legacy of the Rococo, a legacy that was resolutely rejected by Jacques Louis David, whose Oath of the Horatii (Figure 20 40) is the most famous example of a classical model of virtue. This painting, completed in 1784, and illustrating the willing sacrifice of three young men for the integrity of the Roman Republic, was interpreted by the French bourgeoisie as a call to revolution, and David became the painter of the French Revolution. The austere style of the Oath of the Horatii, with its shallow space, its rigorous linearity, its carefully modelled figures and precisely painted archeological details, was to set the model for Neoclassic academic painters of the nineteenth century. While many of them turned out cold and pompous compositions, David was able to use the rigors of the style to create such dramatic and compelling images as The Death of Marat (Figure 20 41). Using a starkly simplified composition, he presents us with the reality of the murder of the revolutionary hero Marat, stabbed in his bath by Charlotte Corday, who had become convinced that the excesses of the Revolution must be stopped. David's skills as a portraitist were in great demand during the period of the Directoire and the Empire. For many of these portraits he drew on the tradition of naturalism that had developed in late eighteenth century portraiture. The work of Elisabeth Vigee Lebrun is an excellent example of this trend. In her self portrait (Figure 20 23) she presents herself calmly and naturally, and we seem to have caught her as she glances up from her work, looking at us as though we were the sitter she is painting. Portraits were by far the most important production of eighteenth¬century English artists who were in demand by both aristocrats and wealthy merchants. The tradition of portraiture begun by the seventeenth century Fleming Anthony Van Dyck still flourished in England. Van Dyck, a pupil of Rubens, had brought an elegant version of Baroque portraiture to England in the early seventeenth century. His portrait of King Charles I is shown in Figure 19 44. Van Dyck's rich texture, loose brushwork, and his elegance were reinterpreted by artists like Gainsborough in the eighteenth [CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] P A G E |8 century (Figure 20¬22). This work is very close to the delicacy and elegant artificiality of the contemporary French Rococo, but without the erotic overtones. Although Gainsborough made his living by painting portraits, he much preferred to paint landscapes, and when he could he set his figures in delicate freely painted landscapes, as he did here. Figure 20 30 shows a very different kind of eighteenth century English portrait, the dramatic rugged military portrait of Lord Heathfield by Gainsborough's chief rival, Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds is best known for his portraits, and like Gainsborough, he preferred to paint in another genre. As the President of the newly founded Royal Academy, he advocated history painting as the most noble, and wrote that one should paint in the "generals manner of the Italians rather than emphasizing realistic details as did the Dutch. His own efforts in this area are not considered nearly as interesting as are his portraits. Benjamin West, an American artist working in London did, however, do a number of very fine history paintings in the grand manner advocated by The Royal Academy. As a matter of fact, he succeeded Reynolds as its president. In his depiction of The Death of General Wolfe (Figure 20 38) West combines heroic sentiment and dramatic Baroque compositional structure with realistic details of the contemporary military costume. While West's innovations would influence much of nineteenth¬century history painting, the work of his contemporary Joseph Wright of Derby would be more influential in the scientific world. His painting of A Philosopher Giving a Lecture at the Orrery (in which a lamp is put in place of the sun) (Figure 20 28) was but one of a number he did depicting the scientific research of his time. He used lighting techniques similar to the seventeenth century Caravaggisti to add drama of this lecture that teaches the orbits of the planets around the sun. His work is an important example of the Enlightenment fascination with discovering the laws of the real world. The American love of the real can be seen in the Portrait of Paul Revere by John Singleton Copley (Figure 20 20). Here we find a somewhat austere and direct portrayal of his sitter without the niceties added by his European contemporaries. One of the greatest of the eighteenth century portraitists worked in sculpture rather than painting: Jean Antoine Houdon. He portrayed some of the most influential men of his age, including Jean Jacques Rousseau, the young Marquis de Lafayette who had returned from America where he had helped to fight for the young Republic, Thomas Jefferson, the old Ben Franklin, and George Washington. He depicted them all in contemporary dress. However, the stoic morality of ancient Rome was an important model to these men for the reshaping of their own times. Artists like Houdon reflected the influence of their ideas in works like the one on Figure 20 24, which shows the philosopher Voltaire dressed in the toga of a Roman senator. However, unlike many later artists who worked in the Neoclassic style, Houdon never lost the immediacy of life, for the old Voltaire is depicted with tremendous vitality. Suggested Images: Figures 19 44, 19 50, 19 54, 20 20, 20 21, 20 22, 20 23, 20 24, 20 26, 20 28, 20 30, 20 31, 20 32, 20 36, 20 37, 20 38, 20 39, 20 40, 20 41, 20 44, 20 50 3~ Architectural Uses of the Past English artists did not contribute a great deal to the development of European visual art during the Renaissance. However, in the early seventeenth century a young architect, Inigo Jones, introduced a vital architectural tradition to England with the building of the Banqueting Hall at Whitehall (Figure 19 74). Jones had utilized many of the motifs and proportions of the Venetian Renaissance architects. Although Jones was strongly influenced by Palladio, the Banqueting Hall shares many features with Sansovino's State Library in Venice (Figure 17 50). Notice how Jones uses similar engaged columns on the facade, a clear and logical structuring of the parts, with emphasis on the horizontal structure of the building, relieved only by the graceful decorative swags at the top of the building. Sansovino had used that motif most effectively, just as he had used a balustrade around the top. Jones did not, however, add statues along the top of the balustrade as had been common on Italian villas. Palladio exerted a lasting influence on Jones through his books on architecture, which served as a source for motifs as well as proportions. Sir Christopher Wren also used many Renaissance details on his masterpiece, St. Paul's cathedral in London (Figure 19 75), but many features, such as the towers, seem to show the more Baroque influence of Borromini. The lower portion of the building is more restrained and classical than the upper section, with the doubled columns of the portico recalling Perrault's facade of the Louvre. Yet these two very different stylistic tendencies are harmonized by Wren. The restrained Palladian tradition introduced by Jones and the more Baroque approach of Wren are both represented in English architecture of the eighteenth century. The Baroque tradition is represented by the great palace of Blenheim (Figure 20 11), built in the early eighteenth century by Sir John Vanbrugh. As Kenneth Clark points out, Vanbrugh was an amateur, a fact used by some critics to explain the somewhat incongruous elements [CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] P A G E |9 he combines in this massive building. Voltaire commented that "if only the rooms had been as wide as the walls were thick, the palace might have been convenient enough." Much more convenient was the group of houses shown in Figure 20 42, the Royal Crescent at Bath, which is a beautiful eighteenth century example of city planning. This group of what would today be called attached town houses or condominiums was laid out around a generops expanse of the common green. The simple classical lines of this building combine elegance and grace of structure with a rare sense of the relation of an individual building to the surrounding space. Of a similar spirit is the eighteenth century villa in Figure 20 1, known as Chiswick house, which had been built near London about 1725. The simple symmetry of this building, the cubic shape crowned by the dome, and the simple classic porch are all reminiscent of Palladio's Villa Rotonda (Figure 17 51). Chiswick House is typical of the so called Palladian style that became so popular in eighteenth century England. The building with its clear symmetrical structure and mathematical proportions seemed a fit setting for the gentlemen of the eighteenth century Enlightenment, men who shared the belief in the power of reason, in the human scale, and in individual dignity set forth so clearly by the Italian Renaissance. Monticello (Figure 20 42), was designed and built some 50 years later by one of the most famous American representatives of the Enlightenment, Thomas Jefferson. Working only from an architectural treatise by Palladio, this talented amateur architect designed a villa for himself that would set the architectural tradition for the mansions of the ante bellum south. Jefferson felt that classical buildings were important democratic symbols for the new republic, and he used a more massive neoclassical style for his design of the state capitol at Richmond, Virginia. Jefferson had seen the Roman temple at Nimes (Figure 6¬46), and reflected its influence in the capitol building he designed at Richmond. The Roman Pantheon (Figure 6 56) served as the model for the library he designed for the University of Virginia in Charlottesville (Figure 20 32). Jefferson was influential in setting the style for official government buildings like Latrobe's capitol building that was constructed in Washington, D.C. (Figure 20 22) in the early years of the nineteenth century. The influence of the more massive Roman classical style reflects the young republic's attempt to identify with the virtues of Roman republicanism. The Americans may also have been influenced by the French architect Soufflot's brand of monumental classicism shown in Figure 20 36. The building, called the Pantheon, is in Paris, and was used by French revolutionaries as a temple to divine reason, a variation of the function of the original Roman Pantheon as a temple to all the gods. The Roman city of Pompeii, which had been completely covered by lava flows in the first century, was excavated in the 1730s and 1740s and the newly discovered motifs offered a whole new repertoire to architects and interior decorators. In the second half of the eighteenth century such classical motifs became popular for interior decoration, particularly in England. Osterley Park House, designed by Robert Adam, is an excellent example of the new style. One room of the house, called the Etruscan Room, is illustrated in Figure 20 37. The ceiling uses the raised stucco technique so popular with the Romans, while the motifs used for the wall decoration—affronted griffins, vases, garlands, and putti, are all taken over from the decorative motifs uncovered in Pompeii. The spare decorative style with its empty spaces and delicate rinceaux patterns was known as the Pompeiian style. How different is the relative austerity of this room from the German Rococo extravaganza from the Amalienburg (Figure 20 14) which was done about the same time. The admiration for classical antiquity became virtually a passion for many eighteenthcentury gentlemen, and it became very fashionable to have bits and pieces from excavations of ancient sites. It also became very fashionable to have classical ruins on the grounds of one's country house. Since the Romans left more walls and military encampments in England than they had left temples, the gentlemen built their own ruins, like the one shown in Figure 20 41. This little building is only a facade and was especially constructed as "aged" ruins. An important aspect of Romantic architecture was the revival of medieval gothic forms; this is called the Gothick Revival. Gothick "follies," or phoney ruins are like the one shown in Figure 20 40. Strawberry Hill (Figure 20 39) is a building that was built by Sir Horace Walpole as a Gothick castle. He used this as his country house. The house formed the setting for recreations of an earlier period, and as a playful escape from his heavy governmental responsibilities. One senses that the eighteenth century Enlightenment love of classical clarity and logic here has come very close to the eighteenth century Rococo love of fantasy and play. This view of the past was popularized by the eighteenth century Roman etcher Piranesi. His famous view of Rome, which looks nostalgically back at the Xglory that was Rome," evokes a spirit that we associate with Romanticism. In another series, the Carceri (Figure 20 33) Piranesi evokes massive Roman ruins in the creation of an oppressive series of prisons. While the Baroque spirit tended to be outgoing and bursting with energy, the Romantic spirit was more brooding and often tried to escape into another age. It is a spirit in opposition to the optimism of both the Baroque and the eighteenth century rationalism of the Enlightenment. [CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] P A G E | 10 The seeds of twentieth century International Style architecture, with its concept that "form follows function," and its honest, economical, and elegant use of materials, are found in such eighteenth century works as the Cookbrookdale bridge (Figure 20¬19). Nineteenth century engineers and architects will further develop these tendencies. In addition the revival of architectural styles begun in the eighteenth century continued in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. After a period of domination by austere building in the International Style, revival styles are again emerging. You might wish to give your students the assignment of seeing how many buildings in their area they can find that obviously use architectural forms from the past. Suggested Images: Figures 6 46, 6 56,17 50,17 51,19 74, 19 75, 2G1, 20 11, 20 14, 20 19, 20 21, 20 22, 20 32, 20 33, 20 36, 20¬37, 20 38, 20 39, 20 40, 2W1, 20 42, 20 44, 20 45, 20 46 Romantic Painting Closely succeeding neoclassicism, the romantic movement introduced a taste for the medieval and the mysterious, as well as a love of the picturesque and sublime in nature (see Romanticism). The play of individual imagination, giving expression to emotion and mood, superseded the reasoned intellectual approach of the neoclassicists. In general, romantic painters favored coloristic and painterly techniques over the linear, cooltoned neoclassic style. French Romantic Painting A follower of David who ultimately turned more to the romantic style was his pupil Baron Antoine Jean Gros, noted for his portrayals of Napoleon in full regalia and for large canvases vividly depicting Napoleonic campaigns. Gros's colleague Théodore Géricault was especially renowned for his dramatic and monumental interpretation of an actual event. His masterpiece, the Raft of the Medusa (1818-1819, Louvre), endows the suffering of the survivors of a shipwreck with a heroic quality. This painting deeply impressed Eugéne Delacroix, who pursued the theme of suffering humanity in such energetic, intensely dramatic works as Massacre at Chios (1822-1824) and Liberty Leading the People (1830), both in the Louvre. Delacroix and other romantics also drew their subject matter from literature and from travels to the Middle East. Delacroix's divided-color technique (that is, color laid on in small strokes of pure pigment) was to influence the impressionists later in the 19th century. During the romantic period, several French painters concentrated on picturesque landscape views and sentimental scenes of rural life. Jean François Millet was one of a number of artists who settled at the village of Barbizon, near Paris; taking a worshipful view of nature, he transformed the peasants into Christian symbols (see Barbizon School). Camille Corot, a painter of poetic, silvery-toned woodland scenes and landscapes, included visits to Barbizon among his extensive travels, portraying the lyrical aspects of nature there, as well as in other parts of France and Italy. English Romantic Painting Romantic landscape painting also flourished in England; the trend began early in the 19th century and is exemplified in the works of John Constable and Joseph Mallord William Turner. Although distinctly different in their styles, both artists were ultimately concerned with depicting the effects of light and atmosphere. Despite Constable's factual and scientific approach—working outdoors, he painted numerous studies of cloud formations and made notes on light and weather conditions—his canvases are poetic, expressing the cultivated gentleness of the English countryside. Turner, on the other hand, sought the sublime in nature, painting cataclysmic snowstorms or depicting the elements—earth, air, fire, and water—in a sweeping, nearly abstract manner. His way of dissolving forms in light and veils of color was to play an important role in the development of French impressionist painting. German Romantic Painting Of Germany's romantic artists, Caspar David Friedrich was the leading figure. Landscape was his favored vehicle of expression. He imbued his hypnotic pictures with religious mysticism, portraying the earth undergoing transformations at dawn and sunset, or in the fog and mists, perhaps alluding thereby to the transience of life. Philipp Otto Runge also devoted his brief career to painting mystical landscapes. Morning (1808-1809, Kunsthalle, Hamburg) is part of an otherwise unfinished allegorical landscape cycle, The Four Phases of the Day. American Romantic Painting [CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] P A G E | 11 America's first truly romantic artist was Washington Allston, whose paintings are mysterious, brooding, or evocative of poetic reverie. Like other romantics, he was inspired by the Bible, poetry, and novels, as is evident in numerous works. Several artists working between 1820 and 1880 are now distinguished as the Hudson River school; their enormous canvases reveal their reverence for the beauty of the American landscape. Thomas Cole, the most noteworthy of these painters, charged his scenes with moral implications, as is evident in his epic series of five allegorical paintings, The Course of Empire (1836, New York Historical Society, New York City). In mid-19th-century landscape painting there appeared a new trend, now defined as luminism, an interest in the atmospheric effects of diffused light. Among the luminist painters were John F. Kensett, Martin J. Heade, and Fitz Hugh Lane. A sense of “God in nature” is apparent in their pictures, as in the earliest works of the Hudson River school. In contrast to the smaller and more intimate luminist works—for example, Kensett's scenes along the Rhode Island shore—Frederick E. Church and Albert Bierstadt painted the spectacular scenery of South American jungles and the American West on enormous canvases. See American Art and Architecture. 19th-Century Nonromantic Painting Although romanticism was the dominant movement in the arts throughout much of the 19th century, other—completely opposite—tendencies existed, and certain painters worked outside any tradition. For example, Francisco Goya, Spain's foremost painter, cannot be defined by alliance with a particular art movement. His early works are in a modified rococo style, and his late works (exemplified by the remarkable Black Paintings on the walls of his home, the Quinta del Sordo) are expressionistic and hallucinatory. In portraits of the royal family—for example, Family of Charles IV (1800, Prado)—he emulated a device used by his earlier compatriot Velázquez (in Las meninas) and included himself at the easel. But, unlike the work of Velázquez, Goya's portraiture was never objective; his psychological acumen reveals the vapidity of his subjects, and his brilliant brushwork bluntly records their physical shortcomings. Romanticism (art), in art, European and American movement extending from about 1800 to 1850. Romanticism cannot be identified with a single style, technique, or attitude, but romantic painting is generally characterized by a highly imaginative and subjective approach, emotional intensity, and a dreamlike or visionary quality. Whereas classical and neoclassical art is calm and restrained in feeling and clear and complete in expression, romantic art characteristically strives to express by suggestion states of feeling too intense, mystical, or elusive to be clearly defined. Thus, the German writer E. T. A. Hoffmann declared “infinite longing” to be the essence of romanticism. In their choice of subject matter, the romantics showed an affinity for nature, especially its wild and mysterious aspects, and for exotic, melancholy and melodramatic subjects likely to evoke awe or passion. 18th-Century Background The word romantic first became current in 18th-century English and originally meant “romancelike,” that is, resembling the strange and fanciful character of medieval romances. The word came to be associated with the emerging taste for wild scenery, “sublime” prospects, and ruins, a tendency reflected in the increasing emphasis in aesthetic theory on the sublime as opposed to the beautiful. The British writer and statesman Edmund Burke, for instance, identified beauty with delicacy and harmony and the sublime with vastness, obscurity, and a capacity to inspire terror. Also during the 18th century, feeling began to be considered more important than reason both in literature and in ethics, an attitude epitomized by the work of the French novelist and philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau. English and German romantic poetry appeared in the 1790s, and by the end of the century the shift away from reason toward feeling and imagination began to be reflected in the visual arts, for instance in the visionary illustrations of the English poet and painter William Blake, in the brooding, sometimes nightmarish pictures of his friend, the Swiss-English painter Henry Fuseli, and in the somber etchings of monsters and demons by the Spanish artist Francisco Goya. France In France the formative stage of romanticism coincided with the Napoleonic Wars (1799-1815), and the first French romantic painters found their inspiration in contemporary events. Antoine Jean Gros began the transition from neoclassicism to romanticism by moving away from the sober style of his teacher, Jacques-Louis David, to a more colorful and emotional style, influenced by the Flemish Baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens, which he developed in a series of battle paintings glorifying Napoleon. The main figure for French romanticism was Théodore Géricault, who carried further the dramatic, coloristic tendencies of Gros's style and who shifted the emphasis of battle paintings from heroism to suffering and endurance. In his Wounded Cuirassier (1814) a soldier limps off the field as rising smoke and descending clouds seem to impinge on his figure. The powerful brushstrokes and conflicting light and dark tones heighten the sense of his isolation and vulnerability, which for Géricault and many other romantics constituted the essential human condition. [CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] P A G E | 12 Géricault's masterpiece, Raft of the Medusa (1818-1819), portrays on a heroic scale the suffering of ordinary humanity, a theme echoed by the greatest French romantic painter, Eugène Delacroix, in his Massacre at Chios (1824). Delacroix often took his subjects from literature, but he aimed at transcending literary or didactic significance by using color to create an effect of pure energy and emotion that he compared to music. Rejecting the neoclassical emphasis on form and outline, he used halftones derived not from darkening a color but from juxtaposing the color's complement. The resulting effect of energetic vibration was intensified by his long, nervous brushstrokes. His Death of Sardanapalus (1827), inspired by a work of the English romantic poet Lord Byron, is precisely detailed, but the action is so violent and the composition so dynamic that the effect is of chaos engulfing the immobile and indifferent figure of the dying king. Germany German romantic painting, like German romantic poetry and philosophy, was inspired by a conception of nature as a manifestation of the divine. This led to a school of symbolic landscape, initiated by the mystical and allegorical paintings of Philipp Otto Runge. Its greatest exponent, and the greatest German romantic painter, was Caspar David Friedrich, whose meditative landscapes, painted in a lucid and meticulous style, hover between a subtle mystical feeling and a sense of melancholy solitude and estrangement. In the Polar Sea (1824), his romantic pessimism is most directly expressed; the remains of a wrecked ship are barely visible beneath a pyramid of ice slabs that seems a monument to the triumph of nature over human aspiration. Another school of German romantic painting was formed by the group called the Nazarenes, who attempted to recover the style and spirit of medieval religious art; its leading figure was Johann Friedrich Overbeck. Notable among later artists in the German romantic tradition was the Austrian Moritz von Schwind, whose subjects were drawn from Germanic mythology and fairy tales. England Landscapes suffused with romantic feeling became the chief expression of romantic painting in England, as in Germany, but the English artists were more innovative in style and technique. Samuel Palmer painted landscapes distinguished by an innocent simplicity of style and a visionary religious feeling derived from Blake. John Constable, turning away from the wild natural scenery associated with many romantic poets and painters, infused quiet English landscapes with profound feeling. The first major artist to work in the open air, he achieved a freshness of vision through the use of luminous colors and bold, thick brushwork. J. M. W. Turner achieved the most radical pictorial vision of any romantic artist. Beginning with landscapes reminiscent of the 17th-century French painter Claude Lorrain, he became, in such later works as Snow Storm: Steam Boat Off a Harbor's Mouth (1842), almost entirely concerned with atmospheric effects of light and color, mixing clouds, mist, snow, and sea into a vortex in which all distinct objects are dissolved. The United States The major manifestation of American romantic painting was the Hudson River school, which found its inspiration in the rugged wilderness of the northeastern United States. Washington Allston, the first American landscapist, introduced romanticism to the United States by filling his poetic landscapes with subjective feeling. The leading figure of the Hudson River school was the English-born Thomas Cole, whose depictions of primeval forests and towering peaks convey a sense of moral grandeur. Cole's pupil Frederick Church adapted the Hudson River style to South American, European, and Palestinian landscapes. Late Romanticism Toward the middle of the 19th century, romantic painting began to move away from the intensity of the original movement. Among the outstanding achievements of late romanticism are the quiet, atmospheric landscapes of the French Barbizon school, which included Camille Corot and Théodore Rousseau. In England, after 1850, the Pre-Raphaelites revived the medievalizing mission of the German Nazarenes. Influence The influence of romanticism on subsequent painting has been pervasive. A line can be traced from Constable through the Barbizon school to impressionism, but a more direct descendant of romanticism was symbolism (see Symbolist Movement), which in various ways intensified or refined the romantic characteristics of subjectivity, imagination, and strange, dreamlike imagery. In the 20th century expressionism and surrealism have carried these tendencies still further. In a sense, however, virtually all modern art can be said to derive from romanticism, for the modern assumptions about the primacy of artistic freedom, originality, and self-expression in art were originally conceived by the romantics in opposition to the traditional classical principles of art. [CHP. 20- ROMANTICISM: THE 18TH AND EARLY 19TH CENTURIES] Discussion topics for this chapter. How does Goya create sympathy or aversion to his painted figures? Use examples from this chapter. What qualities of Romanticism can you identify in Cole, Hicks, and Goya? Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People combines allegory with politics. Discuss. Other topics to consider: Compare the Romantic movement in art and poetry with Neoclassicism. How are they similar? What are the differences? Discuss the new developments in the field of psychology and their relationship to nineteenth-century Romanticism. Characterize what is meant by "sublime," and discuss the qualities of the sublime in Friedrich's Moonrise over the Sea. P A G E | 13