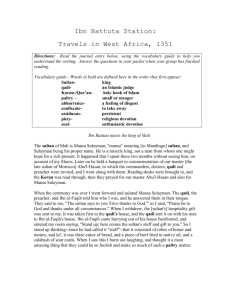

Travels in Asia and Africa - andrew

advertisement